Missing White Woman Syndrome Explained

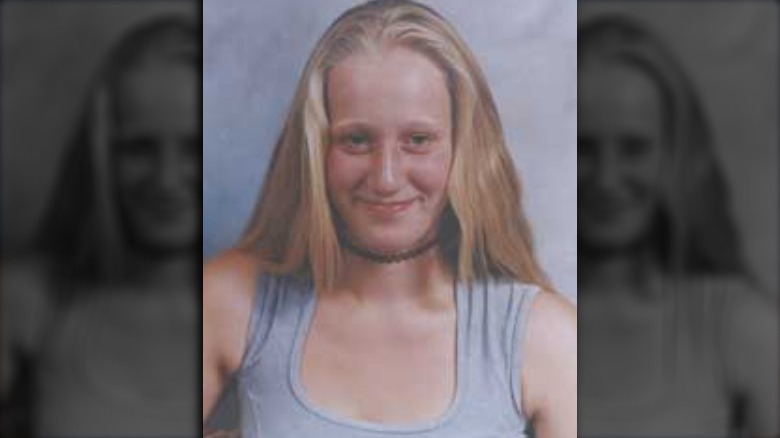

In September of 2021, social media was overrun with pleas to help find the missing Gabby Petito. It's tragic when anyone goes missing, but there was something about Petito's disappearance that captured the attention of America.

Amid the media frenzy, journalist Joy Reid asked (via the Independent), "The way this story captivated the nation has many wondering, why not the same media attention when people of color go missing?"

It turns out, people have been asking that question for a long time. The national media overlooks reporting on missing people of color so often that there's a name for what's happening here: "missing white woman syndrome." It's exactly what Reid is talking about — the tendency for the media to report on the blow-by-blow investigation of a missing person only if the person in question is a white woman.

And there's a lot of missing people they could be reporting on. According to Statista, missing persons cases have been steadily declining since peaking in the late 1990s, but in 2020, there were still almost 550,000 people missing in the United States. That's a lot of distraught families, so why does the public only hear about white women?

Journalist Gwen Ifill and skewed media coverage

The late Gwen Ifill was an award-winning journalist and host of the national Washington Week in Review. The University of Washington says she was the first Black woman to host a news program on that scale. Ifill is also credited with coming up with the term "missing white woman syndrome" to describe the unequal media coverage that was happening in the reporting of missing children and adults.

In 2019, CNN took a close look at the statistics and found the extent of the problem is nothing short of shocking. They looked at cases of missing children in particular and found that in 2015, studies showed that while in an average of 35% of all missing children cases the victim was Black, those missing children were only featured in around 7% of media coverage.

By 2018, things were still bleak. Media still skewed heavily toward reporting on the disappearance of white children, while at the same time Black children went missing at a proportionally higher rate. Even though the racial makeup of children included just 14% Black children, Black children also accounted for 37% of all missing children cases logged with the FBI's National Crime Information Center. Reports on them, though, were few and far between.

The missing white woman syndrome in action

The International Business Times says it's also called the "damsel in distress syndrome" and the "missing pretty girl syndrome." No matter what it's called, journalist Eugene Robinson suggested that if a missing person was female, white, attractive, and at least from a middle-class family, they could count on "24-7 news coverage."

There's actually one case that illustrates the point with undeniable clarity — Jessica Lynch, the U.S. Army soldier who was taken by Iraqi forces and held as a POW in 2003. As History says, she was held for seven days before being rescued, and making headlines around the world.

Not only did Lynch condemn the media and the military for exaggerating her story, but it's also been pointed out that she — the blonde, white woman — was chosen to be the poster child over fellow soldiers Lori Piestewa and Shoshana Johnson.

Piestewa was killed in the attack, a tragedy that made her the first Native American woman to be killed in overseas combat (via the U.S. Army). Johnson was captured alongside Lynch, and it made her the country's first Black female POW, yet those weren't the stories in the headlines. Lynch herself called the media out on her return, saying (via History), "I am still confused as to why they chose to lie and tried to make me a legend when the real heroics of my fellow soldiers that day were, in fact, legendary."

The problem with reporting on the disappearance of Hispanic individuals

Every year, the FBI releases their statistics on missing and unidentified persons, as compiled in their National Crime Information Center. In 2019, they had 87,438 active cases, which were then broken down by factors like age and race. But look closely, and there's something odd about their categories, which are "Asian," "Black," "Indian," "Unk," and "White." "White" has an asterisk beside it, and there's a footnote: "Includes Hispanic."

Wait, what? CNN points out that's a huge problem, and it makes it impossible to actually tell how many Hispanic and Latino children and adults are actually missing — and how underrepresented they are in media reporting. According to the vice president of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, Robert Lowery, various studies suggest somewhere around 20% of missing individuals are Hispanic. There's a good chance that percentage is even higher, and Lowery says, "I think there's a false belief that white children make up the biggest number of missing children when, in fact, (proportionally) it's just the opposite."

Minority disappearances are believed to be underreported

Anyone going by the cases that make mainstream media news cycles might be tempted to think that white women are overwhelmingly the subject of missing persons cases, but a look at the data tells a very different story. And here's the thing: It's likely that story isn't even correct.

Natalie Wilson is one of the founders of an organization called the Black and Missing Foundation, and their mission is putting the focus on the missing individuals that the media tends to overlook. Wilson says (via The Wall Street Journal) that the official numbers aren't even real: "What we're finding with missing people of color is that reports are not always taken or being made by the family. We're noticing that individuals may not know what to do or how to file a police report, or if they did, one wasn't taken because the police say they're [the Black victim] an adult and can walk away at any time."

Wilson told CNN that one of the most widespread reasons a disappearance might go unreported by someone in a minority community is the belief that reports aren't going to be taken seriously, and that they're not going to get the coverage a white woman would. Wilson says that simply put, "There's a sense of distrust between law enforcement and the minority community."

The mis-classification of missing children of color

The AMBER Alert system was first developed in 1996, after the kidnapping and murder of a 9-year-old girl named Amber Hagerman. It started in Dallas-Fort Worth, Texas, and it's grown into a nationwide program that's done a ton of good.

There are a series of guidelines that have to be met in order for an AMBER Alert to be issued, and it's put out when a child — under the age of 17 — is deemed to be in immediate danger, and there's "reasonable belief" that the child has been abducted.

Many times, it's the AMBER Alert that the media picks up on, and this circles around to one part of the reason why minorities are so vastly underreported on. While white girls are more quickly accepted as being the victims of kidnapping, Natalie Wilson of the Black and Missing Foundation says that Black children are often considered runaways — a decision often made by law enforcement without thorough consideration (via CNN).

While they're still missing, they're considered to be voluntarily missing — and that doesn't allow for the issuing of an AMBER Alert, which means that mainstream media isn't going to pick up on the report of a missing child. Wilson says, "We tell parents all the time, you know your child better than anyone else. ... If you believe your child did not run away, you just have to stand firm with law enforcement."

Media, by nature, caters to audiences

When Clara Simmons was working on her master's degree in applied social research at West Virginia University, she took an in-depth look at how the national television media represented missing children. She suggested that part of what was going on here was that the media was essentially choosing which cases to profile based on what they believed their audience wanted to see. In a nutshell, she found that the largest targeted demographic that most prime-time television networks were looking at attracting with their programing was white women.

Simmons highlighted a massive problem in television, and that's essentially the fact that it's not an unbiased source of information. In order for stations to make money and remain viable, she says, they need to choose shows and news stories based on what's going to get the highest number of people tuning in.

And that means cashing in on the missing white woman syndrome. Simmons writes, "This implies an inherent bias in the goals of broadcast television, which could lead to biases in the stories the stations cover."

Northwestern University sociologist Zach Sommers (via NPR) agrees. In 2013, he headed up a massive study that looked at different media outlets and their tendency to report on white women. He suggested it had something to do with "the economic calculus of news coverage," which includes both viewer numbers and ultimately, ad revenue.

Outrage in 2017

Based on the information that was suddenly coming from Washington, D.C., it was looking like kids were going missing in the city at an alarming rate in the spring of 2017. NPR says headlines were suddenly shouting things like, "Does anyone care about D.C.'s missing Black and Latina teens?"

It was suddenly a big deal, such a big deal that city mayor Muriel Bowser needed to call a press conference and explain what was going on. There wasn't an increase in missing minority children, they were just making more of an effort to post these previously overlooked cases on social media.

The announcement was also made by The Washington Post, which explained that in the wake of an appeal by the Congressional Black Caucus, more publicity was going to be given to missing children, particularly those considered "vulnerable." Folded into that was an acknowledgement that it included teenagers who had run away from home, and confirmation that resources were going to be diverted to non-profits with a mission of stabilizing the home lives of at-risk kids.

It's incredibly telling that when missing persons cases — that were active all along — started to be publicized, it had everyone wondering what the heck was going on. Bowser's spokesman, Kevin Harris, explained: "This is what the [social media] policy was intended to do. It was intended to get these teens' faces out there. It was intended to provoke conversation. We don't ever want this to become the norm."

Who decides what is newsworthy?

When The New York Times looked at how viral the disappearance of Gabby Petito went on social media, they also brought up the phenomenon of missing white woman syndrome.

Martin G. Reynolds works at the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education as an executive director, and he says that one of the problems is the lack of diversity in the industry. He explained, "Our newsrooms don't reflect the diversity of the country, and folks in editing roles are even less diverse. Until journalism corrects this, we are going to continue to be more and more irrelevant to the audiences that reflect the future."

It's a bigger problem than most people might see reflected on their television screens and behind the desks of their favorite news shows. A 2020 analysis by NiemanLab found that around three-quarters of American newsroom employees are white, and half are white men. Way back in 1978, the American Society of News Editors set a goal that by the year 2000, newsroom staff should be reflective of the racial makeup of the nation's overall population. That hasn't happened, and it's led to the conclusion: "Journalism has a race problem."

It's not just about race

The term "missing white woman syndrome" sounds like it would be all about racial bias, but it's also about the social and economic class system.

Take the case of British teen Hannah Williams. KentLive calls her a casualty of "missing white woman syndrome," because even though she was white and fair-haired, she was also a 14-year-old girl being raised by a single mother in a working class area of southeast London. She vanished on April 21, 2001, and the only media coverage her disappearance warranted was a few one-line mentions in the "news in brief" sections of various newspapers. When reporters from The Guardian did some digging into why Williams' disappearance hadn't gotten the attention that other girls did, law enforcement was shockingly straightforward.

"One spokeswoman ... who dealt with the Hannah Williams case told me that her mother 'wasn't really press-conference material,' and that the girl's background made it difficult to build a campaign around her," writes reporter Martin Bright.

Williams wasn't found for nearly a year, and it was only during a massive manhunt for another girl — teenager (and middle-class) Milly Dowler — that Williams' decomposing body was discovered where she had been dumped after she had been assaulted and killed by Robert Howard, a serial sex offender with a 35-year record. They also reported that an insider from the police department had confirmed that the difference in the two girls' background may have sealed their fate: "... if Hannah Williams had been a Milly Dowler, she may not be dead now."

Nils Christie and the Ideal Victim

Nils Christie was a criminologist from the University of Oslo, and Wired says he had a whole bunch of revolutionary ideas on crime, criminals, and victims. He wrote that drug use was a public health problem, that treatment worked better than jail time, and he also wrote about what he called the "Ideal Victim."

That's not, stresses the University Press, referring to someone who makes the easiest or best victim of violent crimes — or even the most often targeted — but it's the type of person who most people are willing to believe is the victim, and enjoy "legitimate status" as one.

He has five criteria for becoming an "ideal victim" (via Critical Legal Thinking), and anyone who follows the cases that fall under the umbrella of missing white women will find this familiar. He wrote that the victim in question is most sympathetic — and likely to get public attention — when they're portrayed as weak, being preyed upon while doing something commendable, was in a perfectly ordinary, respectable location, was attacked by someone bigger and stronger, and had no previous relationship with the attacker.

Modifying any one of those conditions, Christie said, was to de-legitimize a person's status as a victim. He was writing in 1986, and decades later, nothing much has changed.

It's a pop culture trope, too

Pop culture is very aware that missing white woman syndrome is a thing, and it shows up in scores of works. One of the most famous might be "Gone Girl," the thriller novel-turned-movie that follows the media storm around the disappearance of Rosamund Pike's character. That's fairly recent, and the fact that it shows up in older works, too, suggests this is something that's been going on for a long time.

In "Murder on the Orient Express," the disappearance of a young white girl from a rich family is one of Hercule Poirot's major discoveries, notes TV Tropes, who even suggests it goes as far back to Mary Rowlandson. She was kidnapped by a group of Narraganset during the 17th century conflicts between the Native Americans and the Puritan settlers, and after she was ransomed, she wrote "A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson." The Women's History Blog says that it successfully kicked off an entire genre — the captivity narrative — and was also great at painting a picture of a holy, devout white woman who became the victim of the "other," and who was ultimately rescued.

Charities are trying to change the narrative

In 2004, the headlines were dominated with names that included Natalee Holloway, Laci Peterson, and the so-called "runaway bride," Jennifer Wilbanks. At the same time, a Black woman from Spartanburg, South Carolina, also went missing — but NPR says there were few people searching for Tamika Huston, and fewer news stories about her mysterious disappearance.

It takes some digging to find out what happened to her — Spartanburg Country reports in just a few short sentences that an acquaintance named Christopher Hampton confessed to killing her.

Her disappearance and death inspired the creation of the Black and Missing Foundation, Inc., a non-profit dedicated to raising the profile of missing men, women, and children who all too often go unreported about in mainstream media. Since inception, they have aided in reuniting hundreds of missing individuals with their loved ones and encouraged anyone who wants to help to do so by sharing stories of the missing on social media, printing and distributing flyers, or making donations.

Social media drives the news cycle

Martin G. Reynolds of the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education says that the news cycle is a very different thing thanks to the rise of social media. In the wake of the viral social media campaign around the disappearance of Gabby Petito, he explained to The New York Times, "Journalism in general tends to be reactionary, and if we see something blowing up on one of these platforms, we're going to jump all over it."

Petito was already a vlogger and active part of the social media network when she disappeared, and news quickly took over platforms from TikTok to Twitter. While some internet sleuths who hoped to make some kind of contribution to the case from behind their keyboards claimed to relate to Petito because she was one of them, the host of the podcast Affirmative Murder, Alvin Williams, says that while it's good that people were on the lookout for her, it was also important to remember that there were plenty of minority victims who needed help from the same social media network.

Williams said, "We can play the game of, 'Oh, it's because she was a vlogger,' and all those things, but we can also see that she is a Gen Z, blonde, petite girl, and that is what gets the clicks." He added, "People are selective with the humanity they see in others."