What Really Happened During The Panic Of 1873?

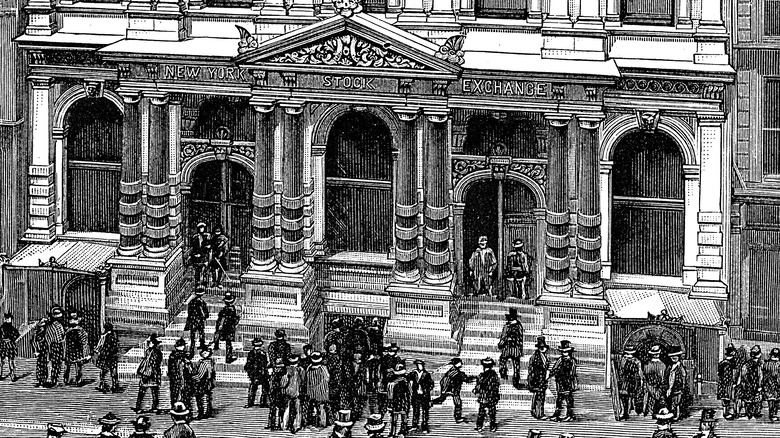

In its history, the New York Stock Exchange has closed its doors for many reasons. Trading was halted after the 1920 Wall Street Bombing, but everything was up and running the following day. There was even a planned closure to celebrate the Apollo 11 moon landing.

But what caused the first ever closure of the New York Stock Exchange, and how long was it affected? The Panic of 1873 wasn't the first financial panic and it definitely wasn't the last, but it had an enormous effect on American society and the Global North. By this point, global economies were intertwined and the lasting depression affected some countries in Europe throughout the 1870s, per the book "Process Safety."

While the depression of the 1930s now holds the title of "Great," the depression following the Panic of 1873 was once known to people as the great financial calamity of their lives. Little did they know that the worst was yet to come.

Jay Cooke & Co. closes its doors

By the 1870s, Jay Cooke & Company was a major bank in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. During the American Civil War, they financed the Union war effort with federal bonds, and after the war ended, Jay Cooke & Co. went into financing railroad construction, according to Northern Illinois University.

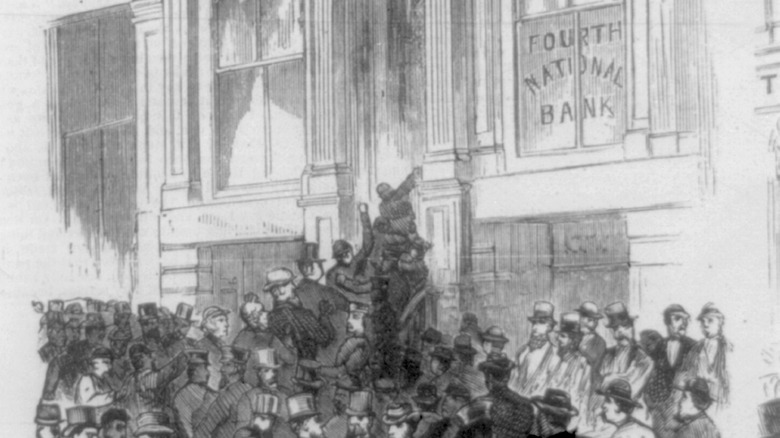

After the transcontinental Union Pacific Railroad was completed in 1869, "businessmen and politicians immediately clamored for another," and so the Northern Pacific Railroad was proposed. Jay Cooke & Co. tried to raise money for the railroad and attract investors, but as PBS writes, by September 18, 1873, they realized that they'd overextended themselves in investments and so declared bankruptcy. Suspending all deposit withdrawals, people and banks around the country panicked.

As large numbers of people across the United States started withdrawing their money out of fear of bank failures, banks had little cash on hand, causing them to call in business loans, "which, in turn, created a downward spiral," according to the book "The 100 Most Important American Financial Crises" by Quentin R. Skrabec Jr.

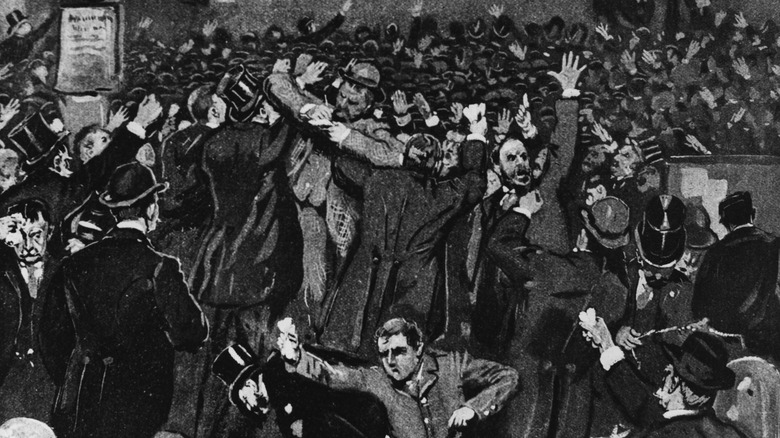

The following day, on September 19, even The New York Times reported, "It was a wild day in Wall street yesterday."

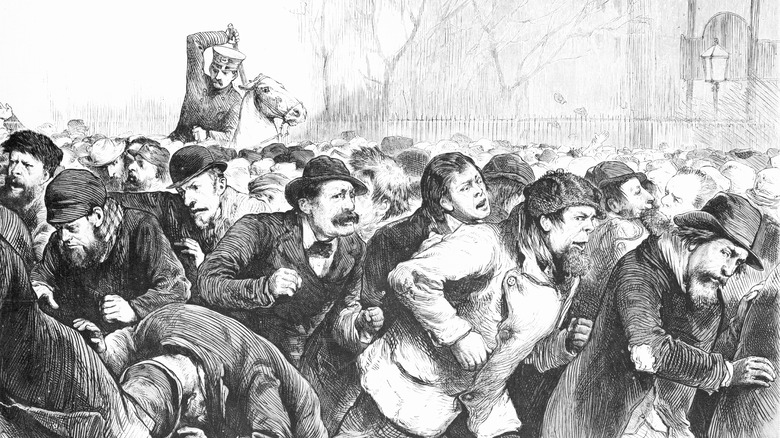

The first closure of the New York Stock Exchange

Due to the panic set off after the closure of Jay Cooke & Co., many at the New York Stock Exchange started frantically selling to protect their money. According to The New York Times, after the announcement on September 18, those who went to the stock market early to sell were able to "protect themselves from loss." But others found themselves in ruin. "Some of the men who were ruined swore, some of them wept, some went out of the street without saying a word; others talked of the trouble in a jovial way and went about trying to borrow money from friends," per Liberty Street Economics.

In response to the panic, the New York Stock Exchange closed for the very first time on September 20, 1873 in an attempt to keep people from selling their stocks in a panic as well as keeping people from taking advantage and buying during the panic. According to the "Routledge Handbook of Major Events in Economic History" by Randall E. Parker, the closure lasted 10 days.

An economic depression in the Global North

The resulting economic depression lasted roughly from 1873 to 1879. According to Liberty Street Economics, it was so severe that it was called the Great Depression before it was superseded by a greater one in the 1930s. Now, the depression caused by the panic of 1873 is known as the Long Depression.

According to Allen C. Guelzo's "Reconstruction: A Very Short Introduction," by the end of September, 1873, 101 banks in the United States had failed, and this number only increased during the depression. Meanwhile, businesses failed left and right, many of them "budding manufacturing businesses," Nikki M. Taylor writes in "America's First Black Socialist." During the resulting depression, it's estimated that between 18,000 and 28,000 businesses failed.

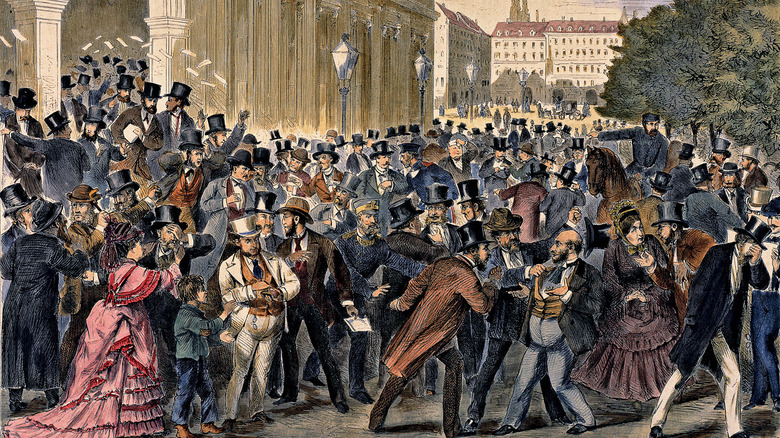

And the depression wasn't limited to the United States. In "Historical Economics," Charles P. Kindleberger writes that Germany and Austria also experienced financial crises, though they'd already been on precarious footing since the Vienna Stock Exchange crashed earlier in May. And as political analysts blamed Jewish people and foreign banks, anti-Jewish pogroms spread across Ukraine and Russia in the 1880s.

However, as noted in Chronicle of Higher Education, for those who had enough money, like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, "the Panic years were golden" and they were able to buy out their competitors "at fire-sale prices."

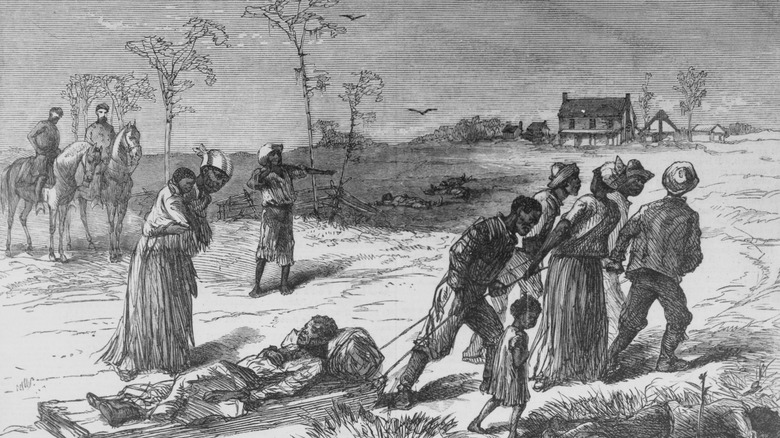

Affecting reconstruction

The panic of 1873 and the resulting Long Depression had an incredibly detrimental effect on the Reconstruction Era that followed the Civil War. The failure of the Freedmen's Savings Bank in Richmond, Virginia in 1874, for example, obliterated over $160,000 in savings, which back then had a purchasing power of over $5 million, according to the inflation calculator at Official Data. And in "This Business of Relief," Elna C. Green writes that the bank also held "collective funds of numerous social-welfare organizations," like labor unions and mutual aid, in addition to the individual accounts for Richmond's Black residents. Although Congress set up a program where depositors were supposed to be eligible to get back up to 62% of what they were owed, Oxford University Press writes that few received that much.

Meanwhile, the panic and its subsequent depression led many politicians to turn away from the subject of Reconstruction racism and focus instead on economic issues. And as Facing History writes, as several Southern states fell into debt, racists tried to blame Black Americans for the economic collapse, despite the fact that if there was mismanagement of the state funds, as in South Carolina, it was done almost entirely by white Republican officials.

With the abandonment of Reconstruction, white supremacists were able to reintroduce racial boundaries, Jackson Lears writes in "Rebirth of a Nation." And amid everything, "lynching remained a more immediate threat than tight money" for Black Americans.

Railroad companies fail

The closure of Cooke & Co. and the panic of 1873 essentially started when North Pacific Railroad bond shares were unable to meet the unrealistic expectations of investors. As banks started closing and other railroads across the country were unable to pay the interest on securities, railroad companies across the United States started declaring bankruptcy as well. As Simon Cordery notes in "The Iron Road in the Prairie State," "the panic was primarily a railroad affair." Over 100 railroad companies failed between September 1873 and the end of 1875. By 1876, a quarter of the country's railroad network was impacted.

The panic of 1873 also severely weakened the railroad unions, and thousands of workers were laid off, forced to work longer hours, or forced to take a pay cut, often in violation of their contracts, according to "The St. Louis Commune of 1877" by Mark Kruger. These conditions set off a chain of railroad strikes, the biggest of which was the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, also known as the Great Upheaval. Over 100,000 workers participated in the strike. Although it was ultimately unsuccessful, it led to an increase in union membership and set the stage for future labor reforms in the 1880s, according to the New York State Library.

Unemployment peaks

With thousands of businesses closing, unemployment rose across the United States. Those who still had jobs witnessed severe wage cuts. Cigar packers, for example, saw their wages go from $3.33 a day in 1872 to $1.67 a day in 1879. By 1876, unemployment had risen to 14%, per PBS, and Nikki M. Taylor writes in "America's First Black Socialist" that by 1877, unemployment was up to 27%.

As unemployment rose, some white Americans chose to scapegoat Chinese people, leading to several violent incidents, according to "Forbidden Citizens" by Martin Gold, including the San Francisco riot of 1877, a three-day pogrom against Chinese residents of San Francisco.

Although irregular or inconsistent employment wasn't necessarily a new thing, because more and more workers were becoming dependent on wage labor, this forced officials to admit that many were out of work "through no fault of their own," according to "Looking for Work, Searching for Workers" by Joshua L. Rosenbloom.