Enemies Of Putin Who Have Died

There comes a time when everyone has to face shuffling off this mortal coil and face the great unknown beyond, but take even the briefest look at the fates of some of Russian President Vladimir Putin's most outspoken opponents, and things get a little weird. How many mysterious deaths does it take before coincidence dips into the realm of, "There's got to be something else going on here?" Well, at least this many.

It's worth stressing, though, that the Kremlin has regularly denied being involved in the deaths of Putin enemies, even when those deaths came by means that were clearly not natural causes. In some cases, independent forensics has confirmed attacks by poisoning — in one case, the application of a Soviet-era nerve gas, which has to be on the list of worst things for any person to experience. Along with, that is, a whopping dose of radioactive material planted in someone's tea.

There have been mysterious plane crashes, executions carried out by shadowy gunmen, poisonings, more poisonings, and a few more poisonings. Although other nations have called out what they perceive as a suspicious lack of effort being put into the investigation into some of the killings, many remain unsolved. Coincidence? Or something more? Here's what is known about the oft-mysterious deaths of some of Putin's most outspoken opponents.

Anna Politkovskaya

Anna Stepanovna Politkovskaya got into journalism early, working as a reporter for Izvestia right after university, and then as an assistant chief editor of Obshchaya Gazeta, before becoming a journalist for Novaya Gazeta in 1999. At Novaya Gazeta, Politkovskaya became nationally known for her reporting, especially due to her writing about the Second Chechen War.

Traveling through Chechnya and Ingushetia, Politkovskaya reported on the human rights abuses "that took place on both sides of the conflict." She was also critical of Ramzan Kadyrov, whom Vladimir Putin installed as the prime minister of Chechnya. RFERL writes that in her last interview, Politkovskaya described Kadyrov as "a puppet [...] coward armed to the teeth and surrounded by security guards. I don't think he will become president [of Chechnya]." Less than one year after Politkovskaya's murder, Putin named Kadyrov as acting president of Chechnya. Politkovskaya was also vocally critical of Putin, and wrote several books that denounced the corruption and human rights abuses enabled and promoted by Putin and his administration, such as "Putin's Russia."

On October 7, 2006, Politkovskaya was found dead in the elevator of her Moscow apartment building. She'd been shot five times, with four of the shots fired at point-blank range. Six men were sentenced to prison for the murder, and although her murder was considered a contract killing, it's never been proven who paid for the assassination.

Alexander Litvinenko

Alexander Valterovich Litvinenko joined the KGB in 1988, and continued his work as the KGB became the FSB in the 1990s. But in 1998, Litvinenko accused the FSB of illegal activities and exposed a plot to murder Boris Berezovsky, who would later be assassinated in 2013.

Litvinenko was briefly arrested for "abusing his office" and, after being acquitted, he fled to the United Kingdom in 2000, where he was granted asylum. There, Litvinenko wrote two books, including "Blowing Up Russia," in which he accused FSB agents of illegal and terroristic activities such as perpetrating the 1999 Moscow apartment bombings. Litvinenko was also outspoken in his criticism of Putin and his "anti-democratic policies and violations of human rights in Chechnya," per the European Court of Human Rights.

On November 1, 2006, after meeting Andrey Lugovoy and Dmitry Kovtun at the Millennium Hotel in London, Litvinenko fell ill. On November 23, Litvinenko died from acute radiation injury, the same day that doctors were finally able to attribute his illness to polonium-210. In September 2021, the European Court of Human Rights found "beyond reasonable doubt that the assassination had been carried out by Mr Lugovoy and Mr Kovtun," according to Reuters. A 2016 British inquiry also concluded that the FSB likely directed the killing. Although the Russian administration has repeatedly denied involvement in Litvinenko's murder, Russian authorities have also failed to carry out an investigation or prove that the assassination was a "rogue operation."

Yevgeny Khamaganov

Yevgeny Khamaganov was a Buryat journalist from the Republic of Buryatia in the Russian Federation, who was known for his articles criticizing the federal government. Writing for InformPolis around 2004 to 2005, Khamaganov was previously detained by the Organized Crime Division and questioned about his trip to Irkutsk and the Ust-Ordynsky district.

Khamaganov worked out of Ulan-Ude, the capital of Buryatia. He briefly returned to his home village after attackers broke his neck in July 2015, but on February 27, 2017, Khamaganov returned to Ulan-Ude.

At the time of his death, Khamaganov was the editor-in-chief of The Site of the Buryat People and Asia-Russia Daily. Although it's unclear exactly what happened, Khamaganov was hospitalized on March 10. Some reports claim it was after being beaten by unknown attackers, while other reports claim that it was because of complications from diabetes. On March 16, Khamaganov passed away in the hospital. A precise cause of death has never been determined.

Sergei Yushenkov

Sergei Yushenkov was one of the leaders of the Liberal Russia party. In spring 2003, he became the second politician from the party to be murdered in Moscow in less than a year, after Vladimir Golovlyov, a co-chairman, was shot and killed in August 2002. Yushenkov had been a member of the Russian parliament since 1990. After Putin became president in 2000, Yushenkov founded the Liberal Russia party along with Boris Berezovsky, who would later be expelled from the party.

Yushenkov was described as an outspoken advocate of human rights who was openly critical of Putin's administration, the FSB, and their actions in the Chechen Republic. But on April 17, 2003, just hours after registering the Liberal Russia party for the parliamentary elections, Yushenkov was shot and murdered outside of his home in Moscow.

Mikhail Kodanev was convicted of contracting the assassination of Yushenkov for $60,000 in order to take control of the Liberal Russia party's funding. Alexander Kulachinsky, the gunman, was also convicted of murder. However, Berezovsky, who was an associate of Kodanev, maintained that Russian authorities were responsible for the assassination.

Nikolai Andrushchenko

Nikolai Andrushchenko, a physicist by training who went on to serve briefly as a city lawmaker, ended up making a name for himself as a journalist at Novy Peterburg, a newspaper he co-founded with Alevtina Ageyeva in the 1990s. As a journalist, Andrushchenko focused on local corruption, criminal activities, and police brutality. He was also an early critic of President Putin and his administration. In 2008, Andrushchenko was even charged with "libel, inciting extremist activity, and insulting a government representative," according to CNN. However, the charges were dismissed.

On March 9, 2017, on the way to a meeting, Andrushchenko was reportedly ambushed and beaten by unknown attackers. He wasn't found for several hours, until a passerby noticed him lying unconscious in the street with a head wound. Taken to the hospital, Andrushchenko underwent brain surgery and was put into a medically induced coma. However, he'd never wake up again and died on April 19.

Although some sources claimed that Andrushchenko had hit his head during a drunken fall, Andrushchenko had publicly spoken about being attacked twice before March 9.

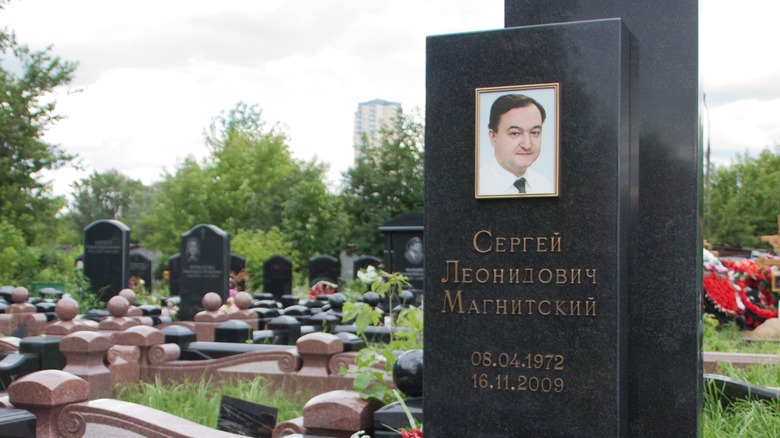

Sergei Magnitsky

Sergei Leonidovich Magnitsky worked as a tax adviser for the investment company Hermitage Capital, which Russian authorities started investigating for tax avoidance in the late 2000s. On June 4, 2007, authorities raided Hermitage Capital's Moscow offices. After the raid, Magnitsky alleged that officials from the Russian Interior Ministry were able to fraudulently take over companies belonging to Hermitage Capital, claim to have overpaid their taxes for the companies, and get $230 million out of the Russian tax system. But after Magnitsky presented formal complaints to the authorities in 2008, the subsequent investigative team ended up arresting Magnitsky on November 24, 2008: Magnitsky had been under investigation since 2004.

Magnitsky was held in detention for 11 months, and on July 1, 2009, he was diagnosed with pancreatitis and gallstones. An operation was scheduled, but on the day of the operation, Magnitsky was transferred to Butyrka prison, which lacked the medical equipment and facilities necessary to treat him. This was also the sixth time that Magnitsky was moved to another detention center.

On November 16, 2009, Magnitsky was found dead in his cell after his condition had deteriorated without treatment. The European Court of Human Rights determined that Magnitsky was imprisoned out of revenge and that the state failed to protect the prisoner's life and health. However, there was no mention of whether Magnitsky was murdered in the court's decision. And unfortunately, Magnitsky's tragic fate isn't so unusual in Russia, where 4,000 imprisoned people died in 2014 alone.

[Featured image by Dmitry Rozhkov via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Boris Nemtsov

Starting off as a provincial governor in 1991, Boris Yefimovich Nemtsov was the youngest governor in post-Soviet Russia. Nemtsov became Yeltsin's deputy prime minister and many thought that he would succeed Yeltsin as president. Instead, Putin became president of the Russian Federation in 2000. Although Nemtsov initially tried to work with Putin, he soon joined the opposition along with his party, the Union of Right Forces, after his party was voted out of the parliament in 2003.

Nemtsov supported Ukraine's Orange Revolution in 2004 and was vocally critical of Russia's invasion and occupation of Ukraine, as well as its annexation of Crimea in 2014. At the time of his death, Nemtsov was involved in organizing a rally in Moscow against Russia's military involvement in Ukraine.

On February 27, 2015, Nemtsov was shot in the back four times while crossing a bridge near the Kremlin in Moscow. According to the BBC, in one of his last interviews, Nemtsov said that he was afraid Putin was going to have him murdered. Almost immediately, the investigative committee into his death claimed that Islamic extremism was being considered a possible motive. The New Yorker reported that a former political adviser to Putin and critic of the Kremlin said that the president was "obviously stunned" by the murder. Five Chechen men were later arrested and found guilty of assassinating Nemtsov after being contracted to do so. However, it's unknown who was responsible for contracting the killing.

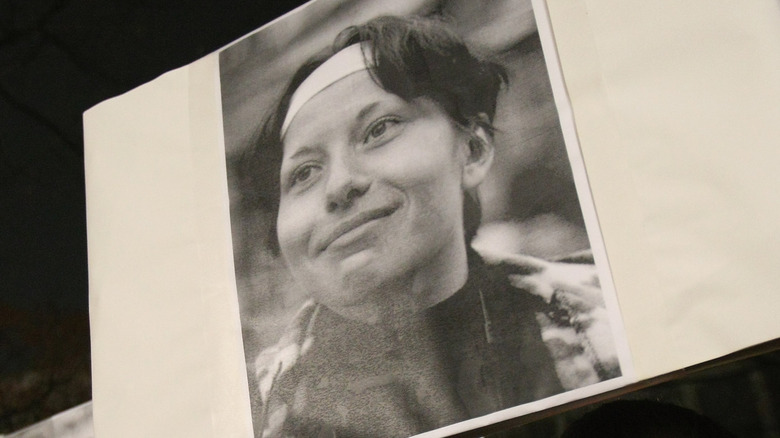

Anastasia Baburova

Anastasia Baburova was a journalism student at Moscow State University. At the time of her murder, she was working as a freelance journalist for Novaya Gazeta. Her work primarily focused on race-motivated crimes and neo-Nazi groups, and Novaya Gazeta was frequently highly critical of Putin's government.

On January 19, 2009, Baburova was covering a news conference at which Stanislav Markelov, a human rights lawyer, disparaged the early release of Yuri Budanov, a Russian army officer who had been convicted of abducting and murdering Elza Kungayeva, a young Chechen woman, in March 2000. After the news conference, as Baburova and Markelov walked and talked, a person wearing a ski mask came up and shot Markelov in the back of the head. As Baburova tried to stop the murderer, she was also shot in the head. Baburova died several hours later, in hospital.

Baburova was the fourth Novaya Gazeta journalist to be murdered since 2000. Nikita Tikhonov and Yevgeniya Khasis, described as members of the ultranationalist group Russkiy Obraz, were convicted of the murders, and Ilya Goryachev was later sentenced to life in prison and determined to be the mastermind of Baburova and Markelov's deaths.

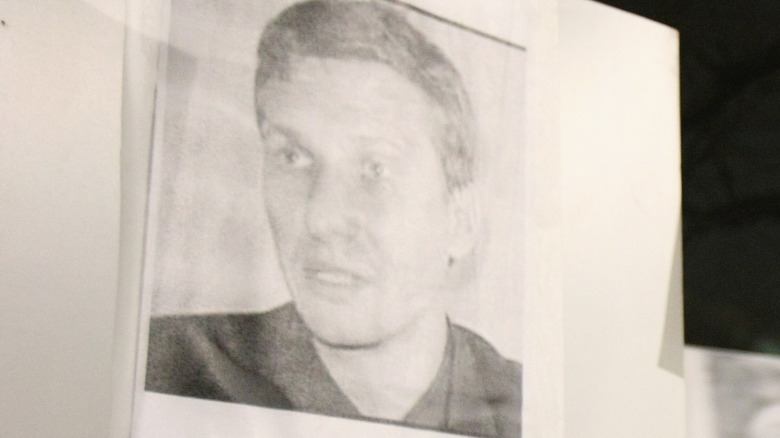

Stanislav Markelov

Stanislav Yuryevich Markelov was a prominent human rights advocate and lawyer in the Russian Federation. Markelov's work often focused on defending people who were victims of police brutality or attacks from neo-Nazis. Markelov was also known for defending dissident journalists and anti-fascists.

Before being assassinated in the same incident as Anastasia Baburova, Frontline Defenders writes that Markelov announced at the press conference that he planned to appeal the early release of Yuri Budanov with the International Court.

Although right-wing extremists were convicted for Markelov's murder, some have questioned whether or not security services were also involved. According to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, these suspicions come out of the fact that the weapon used to assassinate Markelov and Baburova was a "model that was legally only available to military and security service personnel."

Tanya Lokshina, from Human Rights Watch in Moscow, compared Markelov's assassination to Anna Politkovskaya's, describing it as "the latest in a long line of strong critics of the state who have got killed" (via The Guardian).

Yuri Shchekochikhin

Yuri Petrovich Shchekochikhin started working at Novaya Gazeta in 1996, reporting on corruption, organized crime, and the Chechen conflict. The Guardian writes that Shchekochikhin campaigned against the war in Chechnya under Yeltsin and continued his opposition under Putin's regime as well. Shchekochikhin was also critical of what he described as "the resurrection of Soviet methods" under Putin's leadership. After publishing an article for Novaya Gazeta on how the prosecutor-general's office had taken a bribe of $2 million to stop an investigation into a smuggling and corruption case involving Tri Kita, a Moscow furniture store, Shchekochikhin started receiving death threats.

After the corruption case went nowhere — with Prosecutor General Vladimir Ustinov citing "lack of evidence of criminal activity," according to the Committee to Protect Journalists – Shchekochikhin wrote a letter to President Putin, asking him to look into the case in April 2002. After over a year, still nothing had come of the corruption case and Shchekochikhin published another article in Novaya Gazeta on the Tri Kita affair on June 2, 2003.

On June 17, Shchekochikhin fell ill with flu-like symptoms. Within a few days, he was hospitalized as his organs started failing one by one. He also lost his hair, his skin started peeling off his body, and on July 3, 2003, Shchekochikhin died in the hospital. Doctors diagnosed Shchekochikhin with Lyell's Syndrome, but his clinical test results were classified as "medical secret."

Boris Berezovsky

Boris Berezovsky was a former engineer who sold cars after the fall of the Soviet Union. By 1994, he'd survived one assassination attempt that resulted in the death of his driver. According to The Guardian, in 1994, Berezovsky also acquired ORT, a television channel, and used it to help Yeltsin win the presidential election in 1996. Berezovsky wielded a great deal of power in Yeltsin's administration, and when Putin succeeded Yeltsin as president, Berezovsky thought he would be "a pliable successor."

But before long, the two were at odds with one another to such a point that Putin seized ORT from Berezovsky, and the latter fled to London. Berezovsky was granted political asylum in the U.K. in 2003, and in 2007, a Russian court convicted him of fraud and tax evasion in absentia. Meanwhile, Berezovsky accused Putin of poisoning Litvinenko.

On March 23, 2013, Berezovsky was found dead with a scarf around his neck at his home in Ascot, England. Reuters reports that coroner Peter Bedford recorded an open verdict at the inquest, saying that it was impossible to be absolutely certain whether or not Berezovsky killed himself or was murdered. Others have suggested that since Berezovsky was often used as a scapegoat for the Russian government, it's possible that the authorities would preferred him to remain alive.

Natalya Estemirova

Natalya Estemirova started working with Memorial Human Rights Centre, a Russian human-rights organization in Grozny, Chechnya, in September 1999. And she knew from the start what risks she was facing. The Guardian described her death as "both appalling and predictable," especially since she was a close friend and collaborator of both Anna Politkovskaya and Stanislav Markelov. After Politkovskaya's murder in 2006, Estemirova started publishing in Novaya Gazeta. Estemirova was described by Human Rights Watch as "Chechnya's most prominent rights defender." She was especially instrumental in revealing the "mopping-up operation" in Novy Aldy on February 5, 2000, gathering video footage in the days after the massacre and destruction and compiling them with video recordings made by villagers in the film "Aldy."

On July 15, 2009, Estemirova was kidnapped near her home in Grozny and murdered later that day in the neighboring republic of Ingushetia. The Guardian reports that her friends believe her death was "a vile, cowardly, meticulous, state-sponsored execution," meant to scare residents and activists from seeking aid or working in Chechnya.

On September 13, 2021, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that although Russia had failed to properly investigate Estemirova's murder, it didn't find the Russian authorities to be directly responsible for kidnapping or the murder. As of early 2024, no one has ever been charged or prosecuted for Estemirova's murder.

Denis Voronenkov

Despite being a member of the Communist Party from 2011 to 2016, Denis Nikolayevich Voronenkov and his party were considered unofficial Kremlin allies for years. But after fleeing to Ukraine with his wife, Maria Maksakova, in October 2016, Voronenkov became a vocal critic of Putin. According to The Guardian, Voronenkov also claimed that he only supported the annexation of Crimea "because of political pressure."

Euromaidan Press writes that Voronenkov was going to testify against Ukraine's former president, Viktor Yanukovych, and was one of the "main witnesses of the Russian aggression against Ukraine." And on the day of his murder, Voronenkov had plans to meet with Ilya Ponomarev, another former Duma member who fled Russia because he voted against the annexation of Crimea.

On March 23, 2017, Voronenkov was shot and killed in Kyiv in broad daylight. The attacker, identified as Pavlo Parshov, was also shot by Voronenkov's bodyguard and later died in the hospital. Although Ukraine's Prosecutor General Yuriy Lutsenko claimed that Voronenkov's murder was a contract killing, it's never been proven who was behind Voronenkov's murder. Just over a month before his death, Voronenkov voiced concerns that he feared for his life because he was "poking a sore spot of the Kremlin."

Nikolay Glushkov

Nikolay Alekseevich Glushkov was close with Boris Berezovsky, and would end up being found dead five years after his friend's untimely demise. A businessman, who was at one point deputy director of Aeroflot airline, Glushkov fled Russia after he was accused of fraud and sought asylum in the United Kingdom. Glushkov was granted political asylum in 2010, and in 2017, a Russian court found him guilty in absentia of stealing over $118 million from Aeroflot.

This wasn't the first time that Glushkov was put on trial. In March 2004, after being imprisoned for three years, Glushkov was tried in Russia for fraud and attempted escape. Although he was acquitted of fraud, he was found guilty of attempted escape. However, he was released on time served. After Berezovsky's death in 2013, Glushkov was adamant that foul play was involved, and according to NPR, he noted that the list of Russians who opposed Putin was shrinking. "I don't see anyone left on it apart from me," he said.

Five years later, on March 12, 2018, Glushkov was found strangled in his home. Reuters reports that in April 2021, coroners ruled that Glushkov was murdered, but as of October 2021, have been unable to find who was responsible. Glushkov's assassination also occurred just one week after the poisoning of Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia.

Yevgeny Prigozhin

In June of 2023, the Wagner paramilitary group staged an uprising against Russia's longtime leader, President Vladimir Putin. The action was over almost as quickly as it got started, and although there was a lot of news officially unverified, it was confirmed that the head of the uprising was Yevgeny Prigozhin. While many expected Putin's camp to retaliate quickly and with finality, something surprising happened: Nothing much at all.

Prigozhin's mutiny was reportedly being looked at as an ill-informed choice made in error. Unlikely? Perhaps, and it definitely wasn't the end of the story. In August of the same year, Prigozhin was killed in a plane crash, along with nine others. The plane went down about half an hour outside of Moscow, and according to the BBC, the official word from within Russia was that he had been killed "as a result of actions of traitors to Russia."

Interestingly, Prigozhin was later honored as a hero by some of the Russian public, with Eastern Orthodox followers honoring him on the 40th day after his death — the day when it's believed a soul ascends to the final destination. Russia's official media didn't report on it at all, and other media outlets — including the Associated Press — pointed to the Kremlin's silence over his death and the investigation into the cause of the plane crash as looking incredibly suspicious. They went so far as to suggest it was a message: "Anyone who dares to cross the Kremlin will perish."

Alexei Navalny

Alexei Navalny was not only one of the most vocal of Vladimir Putin's critics, but he was largely viewed as the biggest internal threat to his regime. He was at the head of his own political entity, and his organized protests, human rights work, and exposés into Russia's elite galvanized the public.

Navalny was targeted by several attacks that made it clear that his life was at risk, and led to him recovering outside of Russia. When he returned in 2021, he was immediately arrested and ultimately ended up at the eerily-named Polar Wolf penal colony, a dismal, Arctic Circle prison, which he once described (via the Independent) as a place where "I look out of the window. Where I can see it's night, then evening, then night again."

The 47-year-old Navalny was looking at the next three decades in jail, when it was announced that he had died after returning from a walk and collapsing. In spite of the February 2024 reports, Navalny's family has said they're not sure what to believe, and his wife, Yulia, issued a statement saying (via Reuters): "Putin and his government ... lie incessantly. But if this is true, I want Putin, his entire entourage, Putin's friends, his government to know that they will bear responsibility for what they did to our country, to my family, to my husband." Others have also made it clear that they had no questions about responsibility. Navalny's chief of staff, Leonid Volkov, said: "If this is true, then it's not 'Navalny died,' but 'Putin killed Navalny.'"