What Happened After The Boston Tea Party?

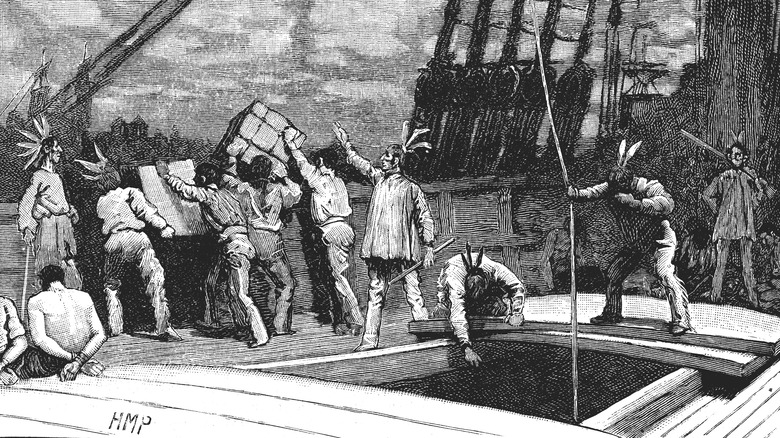

The Boston Tea Party is one of the most well-known and influential acts of protest in American and perhaps global history. Huge quantities of British tea were dumped into the Boston harbor by rebellious colonists, causing huge damages to the British economy in protest of the unjust taxes levied on the crown's subjects across the Atlantic. So what happened to the perpetrators after their protest and destruction of property?

Step one was pretty obvious: get out of Boston (via Boston Tea Party Ship). Many of the perpetrators did not even know each other, and they aimed to keep it that way, silently splitting up and returning to their residences in an attempt to minimize arrests and legal action against the dissenters. The plan worked, as only one man, Francis Akeley, was caught and imprisoned for his role in destroying the tea. As the first organized act against British rule, the Sons of Liberty wanted to set a nonviolent example while avoiding jail time for their members; on both counts, the Tea Party was largely a success.

Founding Fathers were not impressed

While the Boston Tea Party was a landmark moment leading up to the American Revolution, some of the country's most prominent figures in its early stages were against the plan. According to History, while future first President George Washington wrote in favor of the rebellious act, his personal thoughts were much more critical. Washington was not pleased with the conduct of the "mad" Bostonians, and he was not the only Founding Father to be against the plan; an embarrassed Benjamin Franklin offered to reimburse the British East India Company himself. They were wealthy aristocrats, and property meant much to them, even the property of their colonist overlords.

The British monarchy, naturally, was also not too enthused about the massive financial damages of the Tea Party. Parliament passed a series of laws, pleasantly known as either the Coercive Acts or the Intolerable Acts. These shut down the Boston Harbor and ended free elections in Massachusetts, and essentially established martial law in the colony. The laws were drafted in hopes of squashing the rebellion, but it backfired. Colonists saw the acts as tyrannical, and support for the revolutionary cause only grew.