The Deadliest Crowd Surges In History

In the wake of months of pandemic-era lockdown, it's no surprise that many people just want to get out and have fun. There's nothing wrong with that, but crowds can be a dangerous thing — especially when crowd surges happen. That's when there are headlines like the ones around the 2021 Astroworld tragedy: With the death of a 9-year-old boy, that brought the tally of dead up to 10, says CNN. Ten lives lost at a concert — an event that's supposed to be fun, not deadly.

Crowd surges are nothing new, and there are scores of them documented throughout history. Many are even deadlier. But what is a crowd surge, what causes it, and why are they so deadly?

According to Vox, crowd surges are usually sparked by people running either away from something that scares them, or toward something that they want. They turn deadly when there are barriers, poorly laid-out infrastructure, or obstacles that cause a pile-up — often on top of people who have already fallen. Most deaths come from either being trampled or crushed from the press of people from multiple directions, and as long as people have been gathering in large groups, there have been deaths.

Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus (Hartford, Connecticut, 1944)

The world was a mess in 1944, and it's easy to see how a trip to see the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus might have been a welcome reprieve for Connecticut families exhausted by news of the war. Somewhere between 6,000 and 8,000 people showed up for the circus on July 6, and when the fire started, scores were trapped inside a very flammable tent.

Connecticut History says it's never been proven just how the fire started, but it's believed the first sparks came from a lit cigarette, tossed aside against a canvas tent, waterproofed using a combination of paraffin wax and gasoline.

It spread shockingly fast, and as the crowd ran for safety, they found the exits blocked by animal cages. No one knew it, but they had just 10 minutes before the entire thing would come down and kill everyone who wasn't out. Some hacked and slashed their way through the side of the tent, and according to Massasoit Community College, the majority of the 167 dead were killed when they were either trampled by the crowd, or when they jumped — or were pushed — off the bleachers.

The exact number of dead isn't known, and while four circus officials were found legally responsible for the tragedy, they were later pardoned.

Bethel Green Station (London, 1943)

The events of March 3, 1943, are record-setting for terrible reasons. Historic UK says that the day saw not only World War II's largest civilian disaster, but the events that took place that day also resulted in the highest death toll of any single event on the London Underground.

It was a time when air raid sirens were normal. In London, those sounds often meant scores of people rushed for the safety of Underground stations, and it was during one chaotic rush for the Bethel Green station that the crowd surge claimed the lives of 173 people.

Londoners had already been through the Blitz, as per History, and they knew the drill: sirens, then bombers. When the sirens sounded that March, they weren't followed by planes at all. People heard something else: It was new, unfamiliar, and terrifying, and word quickly spread that the Germans were attacking with something revolutionary and even more terrible. Crowds ran for the station, and when one woman — who was holding her baby — tripped and fell, others surged forward over and on top of her.

It was decades before the full story was told to the public. There were no bombs, and no new German weapons. The entire thing had been set off by the unfamiliar sound of anti-aircraft weapons being tested nearby. There had been no actual threat that day.

Collinwood School Fire (Collinwood, Ohio, 1908)

At the heart of the disaster was a furnace. Investigators found that it had overheated and started a blaze first in the basement of the Collinwood School, and it was a fire that would quickly spread. By the end of March 4, 1908, the Ohio town would be mourning the deaths of two teachers and 172 students — 19 of whom were so badly burned that they couldn't be identified (via Case Western Reserve University.

The Cleveland Historical Society says that some — like Niles Thompson — survived by jumping out the school's windows instead of following the crowd as it surged for the doors. Niles, however, was ultimately among the dead: Unable to find his brother, Thomas Thompson, among the survivors, he headed back into the burning building.

Post-fire investigations found that most of the victims had died after becoming trapped in the narrower, innermost set of doors leading out of the school. Pinned there by other children trying to escape, the children were later buried in what one paper described as "one vast procession of hearses and carriages." The disaster prompted major changes to the way schools were designed, and legislation was passed making things like iron staircases and concrete floors mandatory.

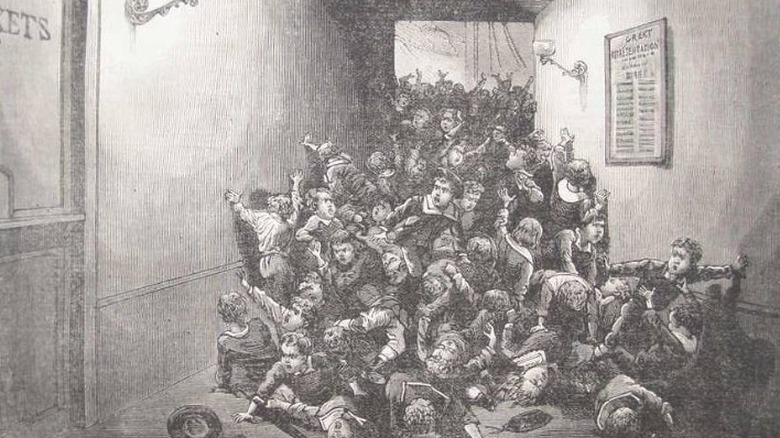

Victoria Hall (Sunderland, U.K., 1883)

In hindsight, it was a recipe for disaster. Take 2,000 children, put them in a Victorian-era theater, and promise them free toys.

That's exactly what happened on June 16, 1883. As the Sunderland City Council details, the Victoria Hall had been open for just over a decade when it was host to a group of traveling entertainers, and what happened should have been predictable. Near the end of the show, the group announced that children with tickets that had certain numbers would be given a prize, and they started handing out those tickets to the kids nearest the stage. Those in the upper galleries — around 1,100 of them — started pushing and shoving their way toward the stairs.

With no adults and no one really in charge, the crowd jammed itself into narrow stairwells and corridors, and that's when kids started to die.

Most of the deaths happened at the front, as children in the back continued to push their way forward, unaware of the fact that they were crushing those at the bottom of the stairs. All 183 children who died — many of whom came from the same families — died of asphyxiation, and ultimately, it was ruled a tragic accident. The hall was destroyed during the Blitz, and according to the Smithsonian, the tragedy kick-started the invention and installation of push-bars on doors.

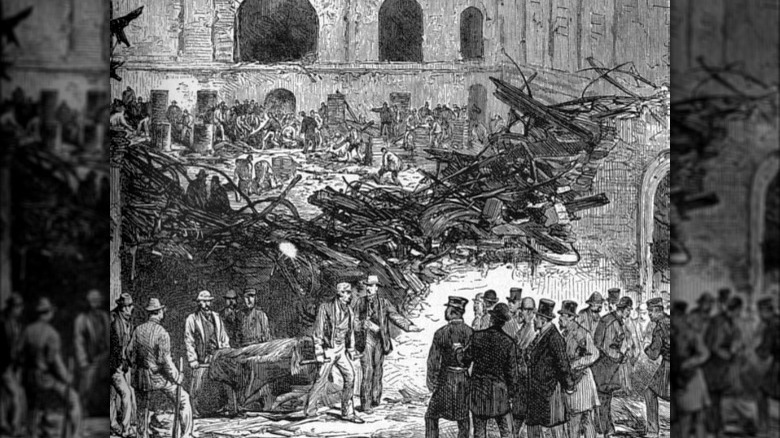

Brooklyn Theater (New York City, 1876)

The holiday season turned dark and deadly in 1876, when New York City families who had been looking forward to Christmas suddenly found themselves sorting through the belongings of the dead instead.

It was December 5 when around 1,000 people went to the Brooklyn Theater to see "The Two Orphans," but before the night was over, hundreds would be dead, reports The Bowery Boys. The play was nearly over when the set caught fire, and although the actors attempted to finish — and avoid a panic — they were driven off-stage as the fire spread. Once the audience realized what was going on, panic was exactly what happened.

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper described the scene (via The Bowery Boys): "... men fell, women fainted, children were trampled underfoot, and the whole spectacle was that of a solid body with a myriad of heads struggling for its life, retarded by its own great weight."

That's nothing short of horrifying. As the crowd pushed toward the exits, theater-goers died when they were pushed off balconies and down stairways, crushed against doorways and stairs, and the living became trapped by the bodies of the dead. The final death toll is uncertain, but it's generally said that the pleasant evening at the theater ended in a makeshift morgue for somewhere between 275 and 300 people.

Estadio Nacional Stadium (Lima, Peru, 1964)

In 1964, about 53,000 people piled into the Estadio Nacional Stadium to cheer on the teams: Peru and Argentina were duking it out to see who was going to be going to the Summer Olympics. According to the BBC, Argentina moved into the lead, and when the ref called a foul against one of Peru's players, player Hector Chumpitaz explained, "This is why the crowd began to get very upset."

The crowd surge started small, with just two spectators rushing on the field. Police intervened, and while Chumpitaz said that reports claiming they'd sent their dogs on the men were exaggerated, they did deliver a pretty swift beating. Some fans headed down onto the field, but many headed for the exits — and that's when the tear gas went off.

Jose Salas was caught in the middle of that surge, and later said that the crowd was packed so tightly that as they moved down the stairs, he never actually touched the ground. He was just sort of carried along, and it was only when he got to the bottom that he found himself in a mixed pile of the living and the dead.

The official cause of death for most of the 300-plus people who died that day was asphyxiation, and things were undoubtedly made worse by conflict on the streets. As some people trying to flee clashed with police, others tried to help those still trapped behind them.

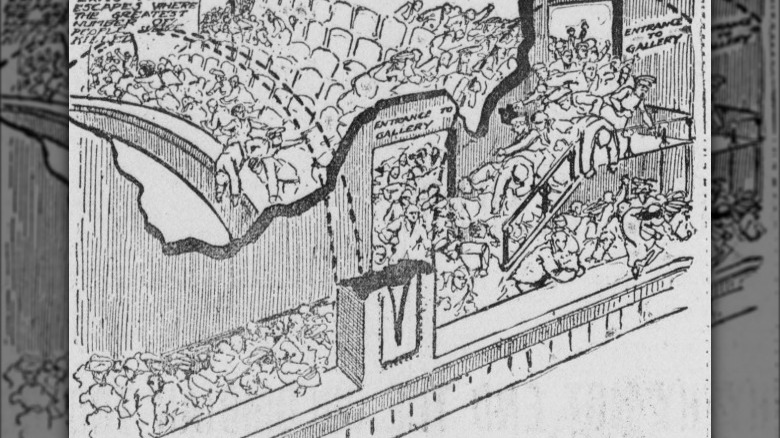

Iroquois Theater (Chicago, 1903)

It was December 30, 1903, when 1,700 people — mostly mothers and their children — woke to the excitement of knowing they were heading to Chicago's Iroquois Theater to see a musical called "Mr. Bluebeard." The day would end with the deaths of 600 of those eager theater-goers.

According to the Smithsonian, the fire started when a stage light sparked, and the curtains proved to be not as fire-resistant as they were thought to be. Eddie Foy, the star of the show, managed to keep things calm only briefly, and he later described the scene he witnessed from stage in his memoirs: "[it was a] mad, animal-like stampede — their screams, groans and snarls, the scuffle of thousands of feet and bodies grinding against bodies merging into a crescendo half-wail, half-roar."

Cast members kicked open a stage door, letting in air that caused fire to billow through the theater. Crowds surged forward in an attempt to make it to the exits, but even those who made it started to die. Fire exits had no ladders, people fell off makeshift bridges thrown down by nearby construction workers, and people were crushed by the crowds behind them. Living people were sandwiched between the remains of those who had been crushed and those who had been burned, and one good thing came of the 602 deaths — an overhaul to building codes, and laws requiring things like emergency lighting in aisles and around exits.

Aimma Bridge Stampede (Baghdad, Iraq, 2005)

In 2005, Iraq saw what The New York Times described as the largest, single-day loss of life since the United States invasion of 2003, leaving 950 dead — and it happened in a crowd of the faithful as they marched to a Shiite shrine, in commemoration of the death of Imam Musa Kadhim.

The shrine itself had just been attacked, leaving seven dead and dozens wounded. That makes it a little easier to see why rumors that one of the men in the religious procession was wearing a suicide belt caused such a widespread panic, and even though it was just a rumor, the crowd lunged forward.

One man described the scene as it unfolded: "... people started shouting about a suicide bomber. They started crashing into each other; no one would look back or give a hand to help the ones who had fallen. People started running on top of each other, and everyone was trying to save himself."

The crowd surge was made even worse by the fact that it passed over the Aimma Bridge. The procession going toward the shrine collided with pilgrims leaving it, and not only were people crushed and trampled: The concrete barriers only served as a funnel, and when the non-concrete barriers broke, people began to drown in the Tigris.

Maha Kumbh Mela Festival (Allahabad, India, 1954)

The Maha Kumbh Mela festival is one of the largest gatherings of humanity in the world — according to The New York Times, more than 80 million people show up to the festival, which is held every 12 years and gets bigger every year. For an idea of just how many people that is, the BBC says that the crowds show up on images taken from space.

It's not entirely surprising, then, that crowd surges have caused scores of deaths, with major events taking place in 1840, 1906, and 1986. The deadliest, though, happened in 1954.

Press photographer NN Mukherjee was there and witnessed how it started. He wrote in his memoir (via The Statesman) that a group of holy men had been passing before a crowd when the mob pushed through the separating barriers and surged forward. Mukherjee wrote, "When the mob came crashing at the slope of the barricade, it appeared like waves made by standing crops when a storm strikes just before they tumble. Those who fell could not rise again. ... I saw with my own two eyes, someone crushing a three-or four-year-old child."

The government denied the scale of the tragedy, but when Mukherjee returned to the site as they were burning "mounds of bodies," he took a series of photos that, once published, made the extent of the event undeniable. Around 1,000 people were killed in the crush.

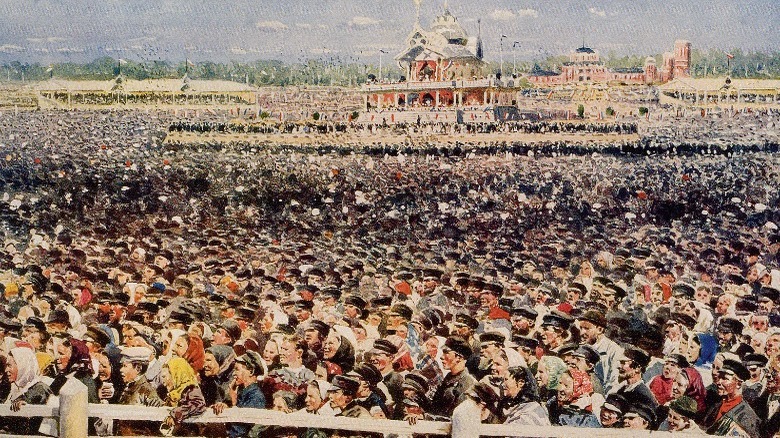

Khodynka Field Tragedy (Moscow, Russia, 1896)

It's not clear how many people died in what became known as the Khodynka Tragedy in 1896. Pieced together from translations of news reports and first-hand accounts at the time, Russia Beyond, put the death toll at 1,389, while other sources — like the BBC — give the equally exact number of 1,429. Between 9,000 and 20,000 people were injured, and it was all because of free gifts and beer that were being given away to celebrate the coronation of Nicholas II.

There were some half a million people who showed up to commemorate the rise of the new tsar ... and, let's be honest, most were probably more interested in the freebies. Gifts were going to be handed out, including engraved cups, scarves, and a ton of free food and beer.

And that's where the problems started. A crowd surge of people determined to get their free food and gifts — including rumors of even more gifts — caused hundreds to be trampled in a scramble that was particularly bad because of the layout of the field. Once used for military training exercises, people tripped and fell in the trenches.

While Nicholas II was pressured into attending a ball afterwards, he also visited the injured, gave families financial support from his personal wealth, and, according to Fedor Gaida, history professor at Moscow State University, gave orphaned children a pension until they were old enough to support themselves (via The Romanov Royal Martyrs Project).

Mecca pilgrimage (Saudi Arabia, 2015)

Images of the hajj — the mandatory once-in-a-lifetime Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca — are nothing short of awe-inspiring. Unfortunately, they're also dangerous.

In 2015, more than 2 million people attended, and according to Vanity Fair, trouble started when two groups of pilgrims — numbering in the hundreds of thousands of people — met in narrow alleys while moving in opposite directions. People were carried along by a crowd that seemed to move without any actual human intervention, and shockingly, those people were alright with it. Until, that is, two opposing streams of people met at an intersection, and the crush of those in the back started to suffocate those in the front. Some died where they stood, and when others fell, the crowd pushed forward and made it even worse. Some were able to climb onto the top of the crowd and get above the crush — even as they reached down and tried to pull others free — but by the end, around 2,400 people were dead.

That wasn't the only time crowd surges turned deadly at Mecca. In 1990, 1,400 people were killed in a crowded pedestrian tunnel, says History. The Guardian adds that a slew of other crowd crushes have been reported: 270 people died in 1994, 118 in 1998, 251 in 2004, and in 2006, there were at least 360 people killed. Those aren't the only years it's happened, either — they're just the most deadly.

Paris Fireworks (Paris, 1770)

As Secrets of Paris details, it was May 30, 1770, and a royal wedding was wrapping up with a display of fireworks, hosted by — and yes, Atlas Obscura says this was a real thing — Louis XV's official pyrotechnicians. The Ruggieri brothers were fireworks geniuses, but that didn't keep the post-wedding show from going seriously sideways when the massive amount of fireworks being fired from the top of a massive wooden temple perhaps predictably set the whole thing on fire. Scores of people from across Paris had turned out to see the show, and then? They ran, fleeing the burning structure down Rue Royale, trampling others as they went.

Still more people were drowned in the Seine when they were pushed in by the hysterical crowd, and even though there were only officially 132 people killed, no historian — contemporary or modern — believes that. Contemporary historian Louis-Sebesatien Mercier wrote that the number was closer to 1,200, while others suggest it was more like 3,000. Louis XV and Marie Antoinette may have donated handsomely to the families of the acknowledged dead, but it didn't stop the talk of outrageous displays of wealth put on in front of starving Parisians.

Feast of Unleavened Bread (Jerusalem, first century)

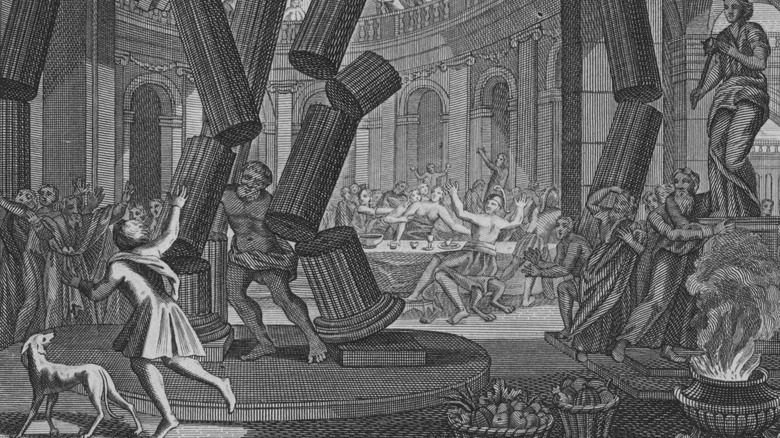

An incredibly early crowd surge was documented by Titus Flavius Josephus, an aristocrat who was writing in the first century.

His "The War Of The Jews" covered a period of 69 years, spanning from Herod to Nero. In it, he tells the rather bizarre story of one pretty stupid, indecent act that turned very, very deadly. It took place at the Feast of the Unleavened Bread, which Got Questions says is the time of the year when the faithful honor their ancestors who fled Egypt during Exodus.

Josephus says that gatherings at Jewish temples were always guarded by armed Romans, and it was one of these Romans who decided it was a great idea to moon those gathered there — and, he wrote, to shout "such words as you might expect upon such a posture."

The crowd demanded that the soldier be reprimanded, but before much of anything could be done, some decided to take the matter into their own hands. The scene turned into complete chaos, more armed guards descended on the temple, and the crowd rushed out into the city. Josephus says that around 10,000 people were killed, writing "this feast became the cause of mourning to the whole nation, and every family lamented their own relations."