The Untold Story Of The Delano Grape Strike

Lasting five years, the Delano grape strike and boycott became known to workers as "La Huelga," or "the struggle" (per Records of Rights, posted at the National Archives). And unbeknownst at the start, it would become a pivotal movement for agricultural workers.

The Volunteer writes that many of the strikers were older and single Filipino men, known as Manongs, who remained unmarried due to anti-miscegenation laws. Faced with an average annual income of $1,400 and with wages falling under the federal minimum wage, the workers believed that they had nothing left to lose and maintained the strike, per History of Yesterday. And in a show of class solidarity, they were joined by Mexican-American workers who refused to allow the California grape growers to instill a racist division among the workers.

After several years of strikes and boycotts, Delano grape workers declared victory. And although some of their successes were short-lived, farm workers across the United States saw the effect of the Delano grape strike and went on to push for their own collective reforms. In her book "The Farmworkers' Journey," Ann Aurelia López writes that by 1977, the United Farm Workers won over 180 separate contracts in several industries, including grape, lettuce, tomato and strawberry. This is the untold story of the Delano grape strike.

Cutting the wages of grape workers

After the colonization of the Philippines passed from the hands of the Spanish to the United States, more and more Filipino men started migrating to the United States and were recruited to work in the agricultural sector. According to History of Yesterday, the United States government specifically sought out young single Filipino cisgender men for labor. "United States capital interests wanted Asian male workers but not their families, because detaching the male worker from a heterosexual family structure meant he would be cheaper labor."

In 1965, grape growers in California were given permission by the U.S. government to hire guest workers from Mexico, also known as braceros, as long as they were guaranteed a wage of $1.40 per hour and they could only be hired if similar wages were being paid to domestic workers. While some California growers agreed to pay all their workers the minimum rate of $1.40 and continued hiring braceros, other growers decided to hire Filipino workers for $1.25 per hour and Mexican-Americans for $1.10 per hour, according to "The Farmworkers' Journey." For some workers, the wages were even lower, closer to 90 cents an hour, plus an extra 10 cents for a big basket filled with grapes, per "Dolores Huerta: Labor Leader and Civil Rights Activist," by Robin S. Doak.

Filipino and Latinx workers unite

On September 7, 1965, Filipino grape workers in Delano, California voted to strike rather than accept the reduced wages proposed by grape growers. The following day, over 2,000 Filipino farm workers walked off the grape vineyards and set up picket lines at the ranch of every grower. The strike was led by Larry Itliong, a member of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC). According to Smithsonian Magazine, the farmworkers were asking for "$1.40 an hour, 25 cents a box, and the right to form a union" in exchange for coming back to work.

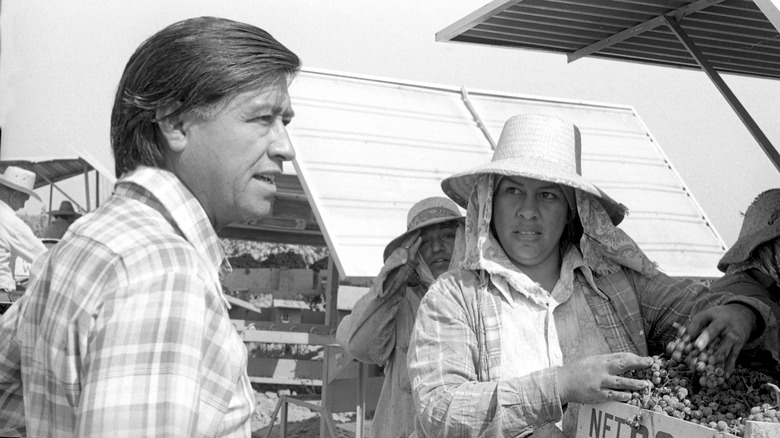

Almost immediately, grape farmers hired Latinx-American workers, predominantly Mexican-Americans, to replace the striking workers. But refusing to let the growers divide the workers, Itliong and fellow striker Andy Imutan reached out to Cesar Chavez, leader of the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), writes the Zinn Education Project. Although Chavez was initially reluctant to join the strike, after taking Itliong's proposition back to Dolores Huerta and the rest of the NFWA members, they decided "in a unanimous vote" to join the Filipinos in their strike. Within two weeks of the start of the strike, Filipino grape workers were joined by the Latinx workers.

Attacks on striking workers

During the Delano grape strike, strikers at the picket line faced incredible violence. The Global Nonviolent Action Database writes that picketers were attacked by dogs, sprayed with pesticides, threatened by cars. The local sheriff would even illegally place people in jail if he believed they might join the picket line.

When the NFWA joined the strikers, they were shocked at how violent the growers were towards the Filipino workers. "Some of them were beaten up by the growers [who] would shut off the gas and the lights and the water in the labor camps," per Dollars & Sense. People driving by in trucks would shoot at and wound workers at the picket line, according to The New York Times, and police also arrested hundreds of workers for violating picket line injunctions as well as assault charges.

In 1968, in an attempt to "draw attention to the violence being used against the striking farm workers and to reaffirm his belief for nonviolence," NBC News reports that Chavez started a fast that lasted 25 days. According to United Farm Workers, this was meant to be Chavez's "act of penitence" for those who'd engaged in violent behavior as well as a "way of taking responsibility."

A poster calling for a boycott of Delano grapes detailed some of the violence that strikers had experienced, which also included being prevented from entering labor camps to talk with other workers, and being forced to attend anti-UFW meetings, or else risk losing their jobs.

A five-year strike

The strike became known as the Delano grape strike and would last five years. According to United Farm Workers, the strike was different from others from the beginning. Filipino and Latino workers picketed together and cooked for one another, the strikes took a "solemn vow to remain nonviolent," and they "drew unprecedented support" from numerous other unions, civil rights groups, and minority groups outside the region.

In 1966, Chavez led the Delano strikers on a 300-mile long march from Delano to Sacramento, according to Asian American Activism. Although the march started with just 70 workers, by the time they reached Sacramento they had 10,000 supporters with them. Across the United States, people donated clothing, food, and money to the United Farm Workers of America (UFWA), which was born a year into the strike out of the union of the AWOC and the NFWA.

Meanwhile, Dollars & Sense writes that the grape growers continued to bring in strikebreakers by any means necessary. And when the Bracero program ended, "Border Patrol opened the border, and trucks hauling strikebreakers roared up through the desert every night. Local police and sheriffs provided armed protection."

Boycotts targeting Delano grapes

The Delano grape strikers also led a boycott against Delano grapes. The first of the boycotts occurred in November 1965, when longshoremen in Oakland "let a thousand ten-ton crates of grapes rot rather than handle the delivery from Delano," according to the Global Nonviolent Action Database. News of the boycott was spread by a campaign coordinated by Huerta, according to The Voluntown Peace Trust, that sent "hundreds of strikers across the country to share their stories."

The NAACP also stood behind the boycott, distributing posters calling for a boycott of California table grapes, which were "picked by people working 10 hours a day in the fields with no breaks and no toilets [...] The family is forced to go on welfare while the growers earn millions."

Smithsonian Magazine writes that the boycott resulted in grocery stores across the United States no longer carrying Delano grapes, and Americans across the country refused to purchase them. According to The Californian, during the boycott 12% of Americans said that they avoided eating California grapes. By July 1968, the boycott against table grapes had gone global.

Aftermath of the Delano Grape Strike

The strike and the boycott continued until July 29, 1970, at which point the strikers declared victory as California table grape growers signed union contracts and agreed to give workers better pay, benefits, and protections. According to the Global Nonviolent Action Database, the UFWA signed contracts that affected 20,000 grape workers. While some companies ended up going back on their agreements, the strike was largely considered a success.

Smithsonian Magazine writes that Itliong would also negotiate the construction of Agbayani Village, a senior home for retired elderly Filipino workers who had no family, and a "percentage of each grape box picked would support the retirement facility."

The success of the grape workers inspired others, and soon after the Delano grape strike ended, lettuce workers went on strike, in what became known as the Salad Bowl strike. According to the University of Colorado, Boulder, the Salad Bowl strike became "the largest farm worker strike in U.S. history," as of 2021. According to The Voluntown Peace Trust, the Delano grape strike also laid the groundwork for the Gallo Wine Boycott of 1973-1978.

When some companies went back on their contracts, the UFWA advocated another boycott of table grapes. Unfortunately, this time the boycott didn't have its original effectiveness.