This Is How Christmas Looked 100 Years Ago

When you think of Christmas and the holiday season, what comes to mind? Snowy hills and sleigh bells ringing? Waking up early as a kid, excited to plop yourself down in front of the Christmas tree and see just what sort of presents were waiting there? Spending time with close family, huddled around a warm, crackling hearth and sharing hot cider? Maybe all of the above?

That's more or less the picture you'd get, thinking through the modern, 21st-century lens. But what if we took a look back in time, heading back about a century? Well, surprisingly enough, Christmas around the early 1920s wasn't as foreign as you might have thought. The holiday was, overall, an especially cozy affair, and a good number of our modern traditions had already started, or were starting right around that exact time.

That said, given what was happening about a century ago, this image of a warm and cozy Christmas is a little more complicated, especially if you look beyond just the borders of the United States. And even within the U.S., while there was plenty of merrymaking to be had, not all aspects of Christmas around the early 1920s were quite so festive. There are some truly interesting — and, occasionally, sad — stories on this front, so here's what Christmas would've looked like approximately a century ago, as told through a (mostly) American lens.

There was a distinctly Dickensian vibe

In a very general sense, if you want to imagine what a 1920s-era American Christmas would look like, then just grab yourself a copy of Charles Dickens' "A Christmas Carol," and you'd have your answer right there. It really is that simple. Even though, wait, doesn't that story take place in England?

Well, it does, but according to Susan Waggoner in "Have Yourself A Very Vintage Christmas," that's exactly what 1920s Americans were going for. World War I had done a number on the psyche of the American public, and a lot of people ached for simpler times. They were nostalgic for the years before all of that disillusionment from the war. And they just so happened to find that in the distinctly Victorian setting of Dickens' novel. Never mind the fact that Americans had largely shunned British holiday traditions in the past; English holly, antique candle holders, even 18th-century parlor art styles — all of it got suddenly transplanted into 1920s America. Multiple December covers of The Saturday Evening Post even featured characters who look like they were pulled directly out of "A Christmas Carol" (via The History Reader).

Oh, and food got much the same treatment. Christmas dinners looked familiarly English, featuring main dishes like roast goose and harboring a particular penchant for plum pudding.

Christmas trees would've looked pretty familiar

To tell the truth, if you went back to the 1920s and grabbed a Christmas tree, then compared it to one from the 2020s, you probably wouldn't find too much of a difference between the two. 1920s Christmas photos from the Homestead Museum paint a very familiar picture: children standing next to a tree, decorated with tinsel, garland, and glass ornaments (not to mention all the presents lying in wait at their feet). None of that would be surprising to find on a Christmas tree in the 21st century. According to the BBC, even the nature of the trees would've even been familiar. Families both then and now would make use of real trees, but artificial trees also started being mass produced in the 1920s — an innovation that's still stuck around years later.

That said, there were some differences. There was the general shape of the tree itself; some other photos from the era feature trees that look much wider and bushier than the tall, conical pine trees that most people are accustomed to seeing in the 2020s. Per Westland London, presents weren't the only things underneath the tree, either; instead, miniature landscapes of wintry Christmas villages could take that place. And that tinsel probably wasn't the tinsel that many people in 2021 are familiar with. It was more likely the precursor to tinsel known as lametta, a type of metal foil manufactured in Germany (via The History Reader).

There was less red and green than you'd think

In the 21st century, it's pretty safe to say that most people associate the colors red and green with Christmas, right? The association of these colors with the holidays feels like a longstanding tradition, but in reality, that history is a little bit foggy.

According to NPR, red and green as Christmas colors likely date back to Roman winter solstice celebrations, but they weren't necessarily widely used for the Christian holiday as it's known today. Rather, the Victorian-era Christmas color palette included blue on top of the familiar red and green. Really, the current view of red and green as Christmas colors likely stemmed from 1930s-era Coca-Cola commercials, which put Santa in red robes (the fact that Coca-Cola is widely associated with the color red is probably not a coincidence, either).

But what about the 1920s? According to "Have Yourself a Very Vintage Christmas," the colors varied a lot. In general, you would've seen a whole lot of red used for varying Christmas decorations — bells, stockings, ribbons, and so on — but very little green. More interesting, though, was the heavy presence of a lot of pastels, like lavender, cream, and rose. Definitely not the colors anyone would expect in 2021, but those colors were in style back in the 1920s fashion world. It was only natural that they would seep into the designs for holiday decorations, too. (The later rise of art deco would even introduce hot pinks into the mix, so purely red and green Christmas decorations have never really been the rule.)

People could gather around the radio

Strangely enough, the radio has always had this weird connection to Christmas. According to the SPARK Museum, there's a story floating around that the first radio program — consisting of some readings of the Bible and a hint of violin music — was actually broadcast on Christmas Eve in 1906. The validity of the claim is a little shaky, but it's a fun anecdote nonetheless.

That said, in America, the radio wasn't exactly a common household appliance for a while. Throughout the beginning of the 20th century, it had largely military applications, especially in the context of World War I. But in the 1920s, things started to change with the introduction of the first radio news program — and first commercial radio station. The radio became used more regularly for entertainment, with over 1 million sets being in use within only a couple of years.

The golden age of radio had begun, with radio being one of the first forms of mass media, per Britannica. As explained by the History Reader, this wider availability of radios, as well as the boom of commercial stations, meant that families could spend their holidays gathered around the radio. People began to demand that the radio stations start playing festive music, and they obliged, seasonal tunes dancing over the airwaves and topping the charts.

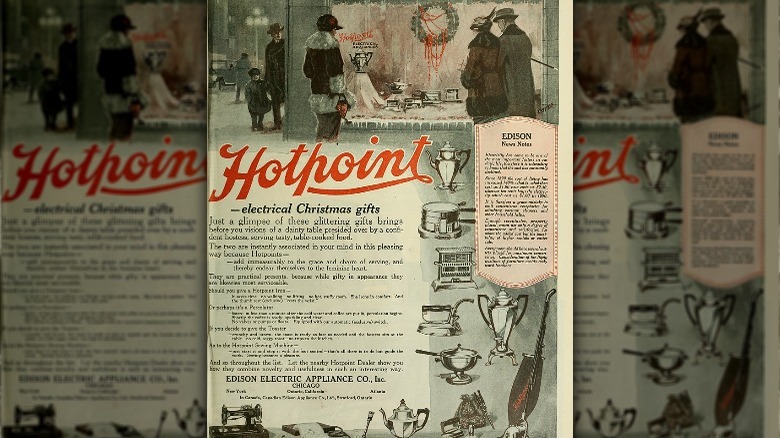

There was plenty of advertising

Now this is probably something that should prove plenty familiar to every stressed-out Christmas shopper of the modern age. All those ads and the ever-looming question of "what do I get these people for Christmas?" Well, a lot of that already existed back in the early 1920s (for that matter, The History Reader would even argue that the financial stability in America T that time was really what made this frenzied gift-shopping into such a time-honored tradition).

The Saturday Evening Post has plenty of Christmas ads heralding from the 1920s, telling shoppers to go buy a wide variety of different gifts for their loved ones, from purses and cufflinks to washing machines and cars. (Also vacuum cleaners, with the ad being aimed specifically at women — even more specifically at wives — because, well, despite some amount of social advancement, this was the 1920s.) And of course, there was the special Christmas aspect that was present in these ads, too. Santa was used to advertise sock sales, and an ad in the Wichita Beacon invited kids to join their "Christmas Club" — a way for them to save up enough money to buy something new the next Christmas (via Holidappy).

Oh, and it wasn't just the print ads pulling their weight. Photos from the era show shop fronts decorated specially for Christmas, putting their products out in the windows. Kids could press their noses to the glass in front of a display for an electric train (via NPR), or maybe adults wanted to ogle at the Oldsmobile making its way out of a chimney (that was a real display, no joke).

Christmas lights brightened the night

According to Popular Mechanics, the tradition of lighting up a Christmas tree for the festivities is a pretty old one. In fact, it might even date all the way back to the 18th century, with the tedious task of attaching candles to a dried-out tree with melted wax. And before you ask, yes, that was a fire hazard — it's definitely a good thing electric lights exist now.

Funnily enough, though, the tradition of using electric lights really got started around the 1920s. Sure, there are some earlier examples of wealthy homes stringing lights on their trees as far back as 1882 but doing so came with a hefty price tag: $300, or the equivalent of $2000 in today's money. So it wasn't super common. But in 1917, Albert Sadacca had the idea to take his family's product — white novelty lights — and add a little bit of color, producing some of the first widely available and safe Christmas lights. (His company — NOMA Electric — would come to dominate the market by the mid-1920s). Even more companies cropped up over the course of the decade, offering boxes of colorful strings of Christmas lights, and their price dropped low enough for the average, middle-class family to afford them. With an increased demand, the industry started to diversify, offering light-up displays featuring snowmen and saints, which eventually led to the creation of expansive outdoor light shows (some of which, like Fresno's Christmas Tree Lane, still continue to this day).

The advertising of the Christmas Orange

If you've never heard of this particular Christmas tradition, you shouldn't feel all too bad about it. After all, stocking stuffers in the modern day and age tend to include small toys and knick-knacks just a bit too small to be wrapped and put under the Christmas tree. But it wasn't quite like that in the past.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, the legend behind this tradition dates back to a story about Saint Nicholas himself, who threw bags of gold through the window of three poor women on the cusp of being sold into slavery. The money saved them, but it also might have started the tradition of filling stockings with gifts on Christmas, since one of those bags landed in a stocking drying by a fire. It might also have played a part in the tradition of specifically placing oranges in those stockings (what is an orange if not just budget gold?)

This tradition was a bigger thing during the Great Depression — families couldn't afford oranges during the year, so getting one for Christmas was a treat — but it likely got its start in America a bit earlier. The citrus market boomed early in the 20th century, and aggressive marketing followed. Folks in January 1921 would've seen an editor for the California Citrograph insisting that a "Christmas stocking is really not properly filled without an orange in it," pleading (and kind of guilt-tripping) readers into buying oranges for Christmas.

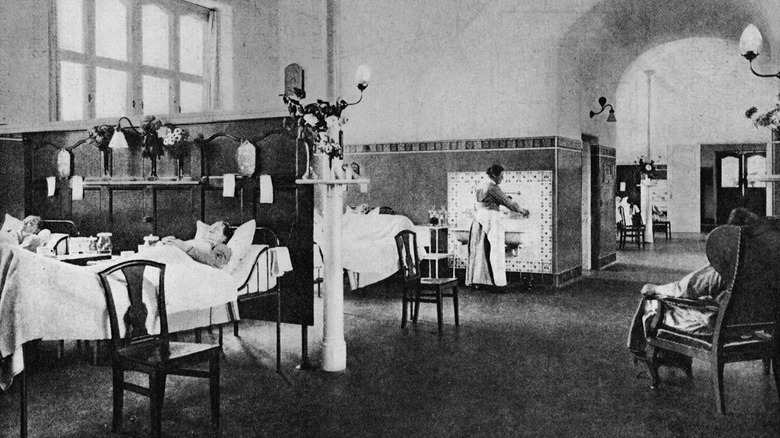

There were some dark scenes in hospitals

When you think of the 1920s, what comes to mind? The parties and flapper dresses — the sort of thing you'd see in "The Great Gatsby"? Or everything that cropped up as a result of Prohibition? The latter definitely doesn't have quite the glamour of the former, does it?

Prohibition played a pretty big part in American society, and it led to some pretty dark stuff on the part of the U.S. government. According to History, it had already tried hard for years to turn people off from drinking alcohol, forcing companies to render their products disgusting and nigh-undrinkable. But with Prohibition and the knowledge that people were still drinking alcohol regardless of federal mandates, the government upped its game. By literally poisoning alcohol. Yeah, the government mandated that toxic chemicals like methyl alcohol be added to alcoholic beverages as a "deterrent." A rather deadly deterrent — one that killed thousands of people over the years.

And poisoned drinks didn't tone down their toxicity for the holidays. Slate tells the story of New York City's Bellevue Hospital on Christmas Eve in 1926, when apparently festive merrymakers stumbled in for help, drunk and violently ill. More than 60 people were reported ill — and over 20 were dead — by the end of the holiday season, leaving hospital staff scratching their heads in confusion over just what was happening. This episode was definitely weird, and even though they were acutely aware of alcohol poisoning, they probably weren't as well-versed in government-sanctioned poisonings.

Germany's post-World War I Christmas wasn't pretty

Hopping back a hundred years ago from 2021 lands you in 1921, but if you go back just a couple years earlier than that, you end up with some much darker holiday tales than what you'd find in 1920s America. After all, World War I had just ravaged Europe a scant few years prior, and, unfortunately, the holiday season couldn't stop a war and its effects; rather, it just got affected by the fighting.

In the direct aftermath of World War I, many of the Allies — particularly in Europe — felt a need to punish Germany, according to the New York Times. A blockade was instituted to stop any food from reaching the country; after all, people in Allied nations were already starving, so why help the enemy? Not everyone necessarily agreed, with President Woodrow Wilson actually asking to lighten the blockade, and he did manage to convince other Allied leaders to allow some food into Germany on Christmas Eve.

But the good will didn't last. The decision was reversed before any food could make it past German borders, leaving much of the population cold, sick, and hungry. Thousands of Germans died in that winter alone, and they wouldn't actually see a scrap of that donated food until July of the following year. Strangely enough, there was more good will to be found during the war. Smithsonian Magazine tells the story of the Christmas Truce in 1914 — an odd case where both Allied and Axis forces hidden in the trenches of France stopped fighting, instead singing songs and wishing each other a merry Christmas.

Christmases across Europe were rough in the 1920s

The effect of World War I on Europe was really, really rough — it's a pretty dark part of the decade that's kind of easy to forget when looking through a modern lens. After all, there's the glitzy and glamorous side of the Roaring Twenties, especially in America.

But Europe at that point looked a lot bleaker, overall. An English author, Coningsby Dawson, spent part of 1920 in Vienna, documenting the efforts of the American Relief Administration (ARA), as well as the poor state of the city as Christmas approached (via Herbert Hoover Library and Museum). He wrote bluntly that "Santa Claus ... forgot to come [to Vienna] or else he had grown tired of paying visits to a people who are so unhappy." The people starved, living in rags and destitute conditions; Dawson even suspected that some families had to sell their children's old Christmas toys at auction for a little bit of money. Children waited in the cold to be fitted for shoes by the ARA, many of them malnourished because they weren't famished enough to deserve foreign aid.

Elsewhere in the world saw even more bloodshed. According to historian Chris Gratien, in 1922, British soldiers were stationed in the Turkish city of Çanakkale. Post-war tensions still flared high, and just two days before Christmas, a few drunken British soldiers began physically and verbally accusing the people of the city. The aggression didn't die down with the coming holiday; instead, just a day later, British soldiers shot and killed a Turkish officer, as well as wounding three civilians.