The Untold Truth Of The Architect Behind The 1893 World's Fair

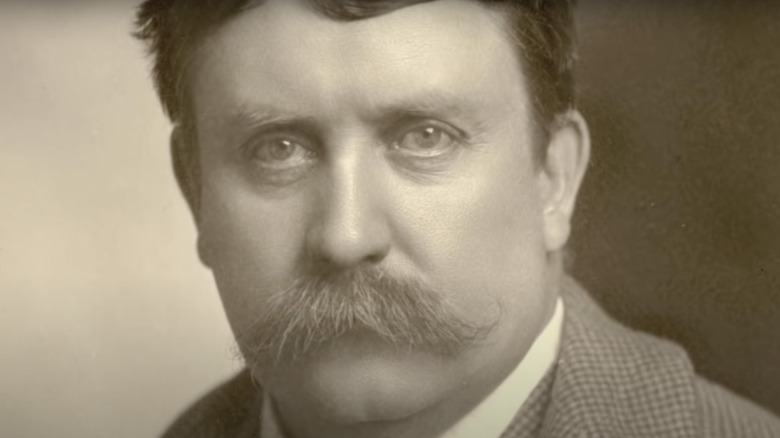

Daniel Burnham is one of those people whose presence can be felt in several urban areas around the world and, yet, no one knows who he is and what all he did. That is unless you are one of the hundreds of thousands of people who read Erik Larson's "The Devil in the White City," which focused on Burnham's and killer H.H. Holmes' life and their intersection at Burnham's tour-de-force project, the 1893 World's Fair (or Columbian Exposition). According to the Chicago Architecture Center, from the experience of the fair, Burnham developed the "Plan of Chicago," which envisioned the growth of the city and influenced urban city planning all over the world.

According to Britannica, Burnham was the sixth of seven children born in New York but eventually moved to Chicago where he would spend most of his life. He was raised within a nonconformist Christian sect that included being educated within their schools and even their tutors when he was applying for college. It would be at this point that he would come to appreciate architecture and apprentice under the likes of William Le Baron Jenney before starting his own firm with John Wellborn Root, where his legacy would be solidified. He wrote his mother in 1868 to tell her that he was going to be "the greatest architect in the city and country" (via Britannica). And while his name doesn't roll off of anyone's tongue, his influence has carried forth into the present day.

Daniel Burnham's wanderlust

While working under architectural firm Loring & Jenney, Daniel Burnham would find himself wooed away from architectural studies and apprenticeship through the wiles of his youth. As Charles Moore wrote in his 1921 multi-volume biography of Daniel H. Burnham, he would be wooed out West by a Colonel Cummings who wanted to create a party to go mine gold in Nevada, so Burnham with his friend, Edward C. Waller, went digging for gold. This would end up being a fool's errand leaving Waller with a significant loss of money and the two of them riding back to Chicago, as it was rumored, on a cattle train.

While Burnham was in Nevada, however, he also ran for state legislature and failed. After returning to Chicago from his trip out West, in 1871, the great Chicago Fire took place, providing him with a significant amount of architectural work in the city. Still being young, he quit. Erik Larson notes in his book, "The Devil in the White City," that Burnham then sold plate glass and became a druggist. He failed at both, later writing that "there is a family tendency to get tired of doing the same thing very long." It would be at this point that Burnham's father would guide him back to architecture under the tutelage of Peter Wight, who hired him as a draftsman — an opportunity of which would introduce him to business partner John Root.

He married the daughter of his first major client

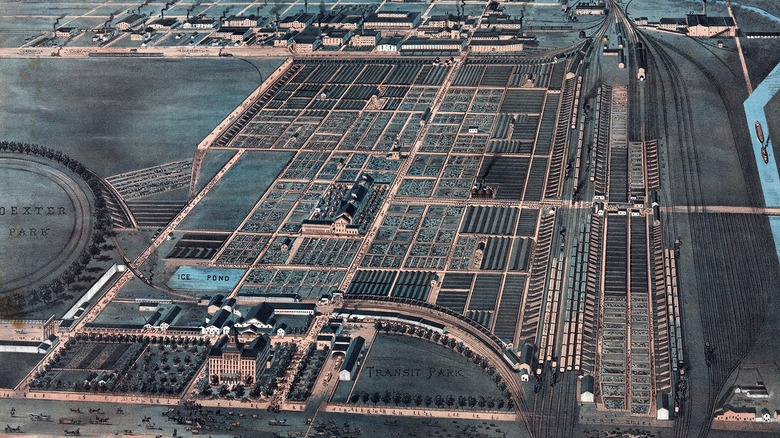

When Daniel Burnham and John Root met in 1872, they decided to start their own firm a year later. And it would be in these early days of their partnership that their first big client would walk in their doors (via Britannica). As Erik Larson describes the scene in his book, "The Devil in the White City," the man "wore black and looked ordinary, but in his past there was blood, death, and profit in staggering quantity." The man was John B. Sherman, who was a longtime livestock business magnate and superintendent of the Union Stock Yards of Chicago. Larson goes on to say that "Sherman ruled an empire of blood that employed 25,000 men, women, and children and each year slaughtered fourteen million animals." This moment would be the boost of visibility Burnham's and Root's firm needed in order for their business to take off.

Sherman wanted them to design his house, and it would be Root who drew up the designs for the house while Burnham was on site controlling the actual construction of the project. It would be while Burnham was on the construction site that a "young, pretty, and blond" girl would come to visit Burnham on the site with the excuse of visiting her friend who lived across the street. Margaret Sherman, John Sherman's daughter, would end up marrying Burnham in 1876. They would remain married until Burnham's death in 1912.

His older brother's crime nearly killed the marriage

In an entertaining tale from Erik Larson's "The Devil in the White City," he tells of how Daniel Burnham's older brother (unnamed) was caught forging checks and damaged their father's wholesale drug business. Burnham's response to this news is an example of a different time, one that was a mixed bag of chivalry and patriarchy — but wild, nonetheless, to modern readers. Larson states that Burnham immediately tried to break his engagement to Margaret Sherman in order to avoid bringing scandal to her and her family. "[John] Sherman told him he respected Burnham's sense of honor, but rejected his withdrawal," writes Larson. "He said quietly, 'There is a black sleep in every family.'"

This was a magnificent moment of grace shown to Burnham by John Sherman. But, perhaps, the grand irony of the whole situation is that even after his daughter's marriage to Burnham, John didn't trust him, Larson notes, thinking the young architect "drank too much." Yet the deeper irony still would find its culmination later when John Sherman would run off with the daughter of a friend to Europe leaving behind his own marriage (via "The Devil in the White City").

He was raised Swedenborgian

According to Britannica, Daniel Burnham's parents raised their children as Swedenborgians and were members of the Church of the New Jerusalem (now the New Church). This Christian religious sect was based on the teachings of Swedish scientist and mystic, Emmanuel Swedenborg, who denied church hierarchy and emphasized service to others as the highest order. In a profile of Swedenborg by The Swedenborgian Church of North America, they speak of his mastery of various fields of study in 18th century Europe and his achievements being everything from "being the first to propound a nebular hypothesis to making the first sketch of a glider-type aircraft," as well designing ship tanks that are used to this day and marketing a usable fire extinguisher.

In his later years, Swedenborg had multiple religious visions and spent the last part of his life writing about religion. He saw Christian scripture as a story of spiritual growth and development, and that the highest order of life was one that was useful to others. He was famous for saying, "All religion relates to life, and the life of religion is to do good."

Considering a good portion of Burnham's early life was in this religious context, it makes sense that Burnham viewed his urban planning work as religious. "His work, which strived to realize Swedenborg's heavenly city in stone, steel and concrete, has shaped much of twentieth century America's urban landscape" (via The Swedenborgian Church of North America).

One of his hotels collapsed and killed a man

Daniel Burnham and John Root started construction of a hotel in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1886. According to an analysis by Gerald R. Larson, professor emeritus of architecture at the University of Cincinnati, Kansas City leaders saw room for urban growth for the railroad town and envisioned a large hotel, usually the first sign of growth in such places. They got Burnham and Root to design what would become the Midland Hotel. Larson notes that Root's biographer Donald Hoffman described the Midland's design as "peculiarly ad hoc: besides the masonry piers, there were circular cast columns and certain brick piers enclosing cast box-columns with rolled columns in the centers." Root utilized the lax building codes of Kansas City to experiment with iron skeletal structures on the outside of the building.

In 1888, the structure above the banquet hall collapsed and killed a worker, Larson details. There was an investigation into who was to blame for the collapse. Burnham and Root were eventually absolved of all responsibilities as they had made the revisions to the plans, but the contractor had not followed them. "Architecture and Building" gives particular expression to the tension of this time period: Burnham, after hearing of the initial news of collapse, went into Root's office and said, "John, we have stuck together in prosperity, we will stick together in failure."

He did urban planning in the Philippines

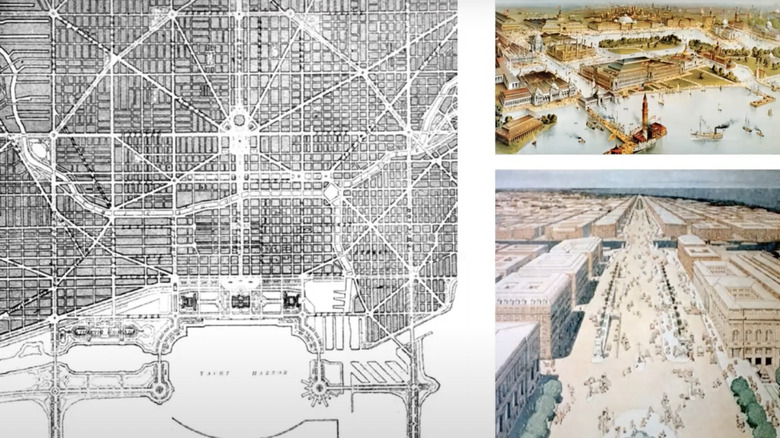

According to the Burnham Plan Centennial, during the winter of 1904-1905, Daniel Burnham won a commission from the United States government to go to the Philippines to develop a city plan for Manila and a brand new "Summer Capitol" called Baguio City, 155 miles north of Manila in the mountains of Luzon. The Philippines had traded hands from Spain to the U.S. in 1898 after the denouement of the Spanish-American War. The U.S. government wanted to show its authority over the new colony with these plans that it hoped would strike both an imperial and progressive tone, as per the Burnham Plan Centennial. Burnham's goal was to optimize urban planning to better control a newly colonized space and people.

The U.S. viewed the Philippines as a territory, which lay outside the bounds of the Constitution. The attorney general stated in 1901 that any law could be imposed "without asking the consent of the inhabitants, even against their consent and against their protest, as it has frequently done" (via City Monitor). Burnham sought no input from the Filipino people, instead replicating elements of the grid systems of Washington D.C., making all of the buildings and structures circulate around the main building of government because "every section of the Capitol City should look with deference toward the symbol of the Nation's power." Anti-colonial sentiment back in the states would lead to a return of power to local Filipino governance, which still utilized parts of Burnham's plan

He was a part of the City Beautiful movement

In the wake of the 1893 World's Fair, a new movement came into existence called City Beautiful with Daniel Burnham at its helm. The New York Preservation Archive Project notes the movement's guiding light was the idea that a city was more than just a symbol of economy and industrialization but also something that contributed to the lives of those who lived there.

The movement came in the midst of America's severe industrialization where factories emitted smoke into the air and soot covered everything. City boards and leaders came to understand that the morale of inhabitants would need to be tended to through urban aesthetics. The planning of a city came into existence, and architects across the country took note.

While architects like Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright sought out a specific "American-ness" to their designs and planning, Burnham and the City Beautiful movement saw the disposal of European tradition and past styles to be a form of insecurity, so "the provenance and thrust of City Beautiful planning was classical and Baroque in its emphasis upon processions of buildings and open spaces arranged in groups" (via the Encyclopedia of Chicago). Burnham often said, "Make no little plans, they have no magic to stir men's blood. ... Make big plans ... remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing asserting itself with ever growing consistency."

He was the first chairman of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts

According to the Commission of the Fine Arts, the commission was created in 1910 as a means to organize and advise on those elements of the arts and of national symbols, as well as guiding the design of Washington, D.C. The commission's role was guided by the City Beautiful movement, as well as the 1893 World's Fair (both helmed by Daniel Burnham) and was attempting to elucidate through art and design America's role as a world leader. As the commission also notes, the group also formed in response to the Progressive Era, which was marked by a "widespread cultural belief in the moral agency of civic art to counter the effects of industrialization." It seems that Burnham's urban planning visions and principles were key to the very aesthetic operating procedures of the U.S. government.

Seven prominent designers, including Frederick Olmstead, the landscape designer for the World's Fair, became the first commission with none other than Burnham as its chairman. The tendril of the government would play a role in the design and aesthetic consistency and symbolism throughout various national parks, monuments, and cities (via Commission of the Fine Arts). Yet it seems that its very existence was dependent on the work and ideas of Burnham himself.

Daniel Burnham was one of the first environmentalists

The Burnham Plan Centennial placed Daniel Burnham within the context of the history of environmentalism while notating that he, himself, would not have called himself an environmentalist. They offer that Burnham understood nature to be more than an "aesthetic experience," and, in fact, could directly affect commerce by improving workers' quality of life and therefore efficiency in the workplace. According to this description, Burnham's environmentalism was secondary to its ultimate utility to industry, optimizing the ability of the workers to produce in order so corporate profits could continue to grow.

As Chicago-based architectural firm Moss discusses, Burnham's plans for Chicago, especially the park systems on the south side, were significant to the drive of green urban design. He envisioned interconnected transit, a network of boulevard streets, a regional train, a network of highways, and plenty of lakefront public space, which Moss notes many of which did come to fruition. While industry may have been forefront in his mind, it does seem as if Burnham sought to incorporate natural landscapes into the city's design so that all residents would be able to escape the grind of their daily life.

He is linked to the Titanic

According to Chicago historian Ray Johnson, on his blog Chicago History Cop, Frank Millet came to Chicago in 1891 and became a professor at the Art Institute. Two years later, Daniel Burnham would appoint him the director of decoration for the World's Fair. In fact it was Millet who decided on the white color of all of the building, thus leading to the nickname of "The White City." Burnham's and Millet's friendship would last for well over a decade before coming to an abrupt end.

In 1912, Millet took a trip to Rome for American Academy business — which he had been a secretary for from 1904-1911 — and on his way back to New York, he walked on board the RMS Titanic in Normandy, France. Burnham and his wife were heading in the opposite direction in the Titanic's sister ship, the RMS Olympic. As Johnson details, the ships were supposed to pass each other on that fateful evening of April 14, and in doing so, Burnham hoped to touch base with Millet. When Burnham attempted to send a message, he was told it couldn't go through because the Titanic had been involved in an accident.

'The Devil and the White City'

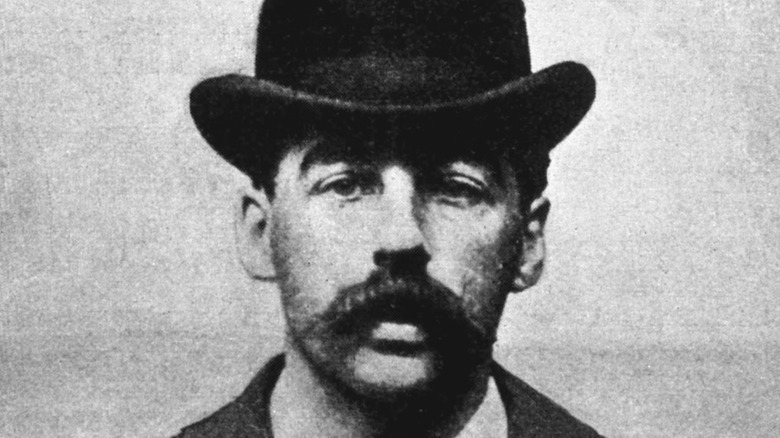

The central drive of Erik Larson's book, "The Devil in the White City," is the intersection between Daniel Burnham's life and the beginning of his national fame with the design of the 1893 World's Fair and H.H. Holmes' life and the murders he committed during the same fair. As History put it, "Holmes took advantage of some of the many visitors to the city, including young women who came to Chicago for jobs at the fairgrounds." Burnham could not have known that he was delivering unlucky people into the hands of a killer, yet the culmination of his design work did exactly that, leading to one of the most intriguing cases of serial murder.

According to Victoria Lautman, who wrote about Larson's book in "Chicago by the Book," "Like Burnham, Holmes was egocentric and ambitious, able to maintain a sociable public persona while under astonishing duress. And as sole designer of the so-called Murder Hotel, he was a de facto architect." If the reports at the time are to be believed (and they are still argued about by historians), Holmes' hotel, built to accommodate the influx of job seekers, was rigged with soundproof rooms, secret maze-like passages throughout the building, and trap doors that led to a homemade crematorium in the basement (via History). In order to construct with that level of intention, Holmes would have needed the type of mind that someone like Burnham had. Both men will be forever connected by the popularity of Larson's book.