What Really Happened When London Flooded In 1928

Throughout its history, London has seen its fair share of floods. And even in the 21st century, large parts of London have between a 1% chance and 3.3% chance of flooding every year. But the events of the 1928 London flood remain, as of 2022, unmatched.

Thousands were displaced as their homes were destroyed beyond repair in the flood. And despite the fact that financially-impoverished residents were more severely affected, the government refused to investigate the role that poverty played in the death toll.

Between 2000 and 2015, the number of people worldwide living in flood-prone areas increased by almost 25%, and that number is only expected to rise due to climate change. And the effects of climate change aren't borne equally, instead, it is "disproportionately affect[ing] those who suffer from socioeconomic inequalities." With this in mind, it might be worthwhile to look back on an earlier incident where a natural disaster raged through a city, disproportionately affected those more financially insecure than others, and the time it took for an actual solution to be administered. Here's what really happened when London flooded in 1928.

'When it's up to their manes'

The Thames River has transformed drastically over the past two millennia. According to "The Fabric of Space" by Matthew Gandy, the tidal range of the Thames has increased from less than a meter to over seven meters between the Roman period and the 21st century. Now, the tidal floodplain of the Thames is almost 35,000 hectares, extending from west London into "large parts of central and east London, as well as significant coastal areas of Kent and Essex bordering the Thames estuary."

There were legislative and engineering responses to the flooding of the Thames, such as the Thames River Prevention of Floods Amendment Act of 1879, also known as the Metropolis Management Amendment Act. This required those who owned land by the Thames to maintain flood defenses.

However, flood predictions were still incredibly rudimentary at the time. In "London's Strangest: The Thames," Iain Spragg writes that the remnants of the Victorian early-warning system can still be seen today. Along the side of the raised walls along the sides of the Thames, there are a series of cast-iron lion heads known as the Thames Lions, designed by sculptor Timothy Butler. Installed during Joseph Bazalgette's construction of London's sewage system, "When the lions drink, London will sink/ When it's up to their manes, we'll go down the drains."

A Christmas blizzard

The Christmas Blizzard of 1927 was reportedly the most severe snowstorm that London had experienced in half a century. Central London saw almost 10 inches of snow while the Cotswolds saw up to 24 inches. In many areas outside of London the snow remained past New Year. But as the southerly wind brought a rapid thaw, followed by heavy rains, all the rain and meltwater ran into the Thames, according to "Reginald Sutcliffe and the Invention of Modern Weather Systems Science" by Jonathan E. Martin.

The water level rose during the night of January 6 and during the early hours of January 7, the embankment wall by Lambeth Bridge collapsed, opposite the Tate Britain Museum, causing floodwater to surge into the city of London, per the Tate. As water seeped into peoples' homes and the streets, many could do nothing but seek higher ground and simply watch the water, waiting for it to dissipate.

The surge at Southend was only 4-5 feet above normal, but in London, the flood produced the highest water levels the Thames has ever seen. Peaking at 1:30 AM, the water levels in London were over 18ft, which was the limit of the flood defenses. And despite the fact that the worst of the flooding only lasted a few hours, many people lost their lives to the floodwater and the city suffered an immense amount of damage.

Thousands made homeless

In just a matter of hours, thousands of people lost their homes and all of their belongings. According to SurgeWatch, it's estimated that up to 4,000 people were made homeless due to the 1928 London Flood. Those living in low-income neighborhoods were the most severely affected, since many of the "narrow slum streets in London" ended up submerged in 4 feet of water.

It's estimated that at least 14 people drowned due to the floodwater, many of whom were financially insecure people living in tenements. The Sydney Morning Herald wrote about one man, Alfred Harding, who tragically failed to save four of his daughters who slept in one room in a basement amidst the floodwaters. Unfortunately, "the water was so deep that though he is a powerful man and made prolonged desperate exertions he had to give up."

Soon after the floodwaters started to recede, the Mayor of Bermondsey announced that up to 1,000 homes were now "uninhabitable" because the floodwaters were contaminated with creosote tar. Many families didn't attempt to return even when the water had washed away, and those who did return were subject to sightseers. "Wherever a window was open, even on the ground floor, there would be a group of gazers exploring the poor pretense of a home with a sort of inquisitive sympathy," writes The Guardian. Some people reportedly even tried to take advantage of peoples' desperation and "charged fees for people to view the damage in their homes."

Filling the Tower's moat

When the Tower of London's moat was originally dug by Henry III during the 13th century, it was meant to act as a defensive ditch. His successor, Edward I, was the first one to connect the moat to the Thames and fill it with water. But according to CityMonitor, because of the varying levels of the Thames and inconsistent drainage, the moat became more of an "unpleasant bog."

Eventually, the Tower of London's moat became such a vector for disease, with several Tower soldiers dying from a cholera outbreak, that it was drained in 1843. And with this draining, the Tower of London's moat remained a ditch for over 80 years. Until, that is, the London Flood of 1928. As the Thames flooded London, it ended up filling up the Tower of London's moat for the first time since the 1840s. The Poverty Bay Herald reported at the time that "the Tower looks like its old self after centuries. The moat is 15 ft. deep and 2 ft. of water is upon the Guards' drill-ground."

Considering the damage that the floodwater did above ground, the damage done underground was almost unfathomable: "Underground railways [were] dislocated by floods and power houses [were] paralyzed." Many train stations were flooded, including "some upriver such as Putney," writes Londonist. Meanwhile, the Blackwall and Rotherhithe tunnels became completely inaccessible. Places like Westminster Hall also flooded, as did Lots Power Station and Wandsworth Gas Works.

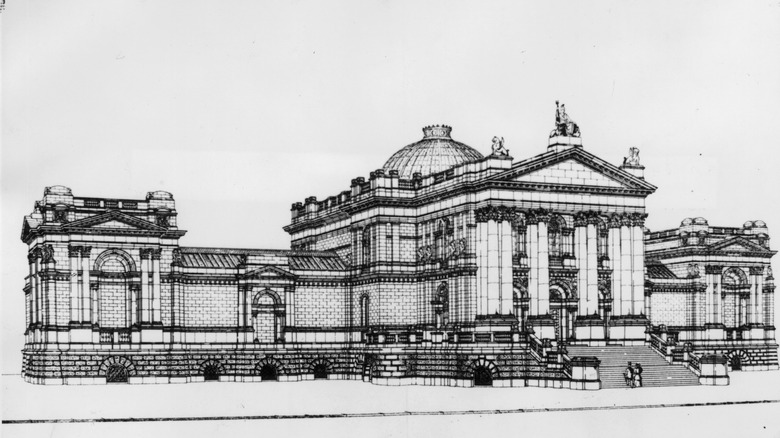

Damage at the Tate Britain

When the wall by Lambeth Bridge collapsed, the Tate Britain became one of the first places to sustain flood damage. According to Tate Britain, there was also the added misfortune of water making its way up through the floors due to "vaults incompletely filled following the 1892 demolition of Milbank's previous occupant, Millbank prison."

In total, 18 works of art were destroyed beyond repair. In addition, over 200 were "badly damaged" and over 60 were "slightly damaged." But over 100 ended up only being "submerged but not damaged," including the newly created Whistler mural in the restaurant. And apparently, the artworks weren't the only things that had to be saved. Tate Britain director Charles Aitken reportedly had to be rescued after falling down a flooded manhole.

But while some paintings were thought to be ruined, they ended up finding their reincarnation in the 21st century. "The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum" by artist John Martin was thought to have been destroyed beyond repair until 2010, when the museum's conservationists reexamined it. A viewer may be able to tell the restorer's brushwork if they look very closely, but restorer Sarah Maisey "wanted the overall impact of Martin's work to have been retained," per NPR.

What caused the London flood?

There were a number of coinciding factors that made the 1928 flood the worst flood that London has ever seen. The melt from the Christmas snow followed by the rainfall was bad, but it may have been manageable on its own. But combined with "astronomical high tides" due to gale force winds creating an "abnormal" and "extraordinary" rise in sea level during "high water of a springtide," conditions lined up for a disastrous flood.

And although the Thames experiences surges regularly, not every surge is necessarily deadly. A surge in 1922 caused the sea level at Southend to rise "11 feet above the expected level," but because it occurred two hours after low tide, Matthew Kelly writes in The Thames Barrier, "there were no serious consequences." Meanwhile, the surge in 1928 only rose 5 feet above sea level, but because it came during high tide, the resulting flood was disastrous.

According to "Inhabitable Infrastructures" by CJ Lim, all of this was only made worse "by capital dredging which made it easier for seawater to flow up the Thames during high tide." Capital dredging of the Thames between 1909 and 1928 ended up increasing the flow of the mean tide by about 4% and increased the tidal range by almost a full meter. While this may have been minor on its own, it "certainly made the situation worse" during the 1928 London flood.

Aftermath of the flood

It would take years to repair the damage caused by the flood. The damage in the Bermondsey district alone was estimated to be around $136,000 in 1928, the equivalent of more than $2.2 million today, according to SurgeWatch. Meanwhile, many who lost their homes were uninsured and businesses that did have insurance didn't have coverage for floods, per the University of Manchester.

In response to the flood, the river walls and embankments were raised, but if this were to continue this would've ended up completely blocking the river from view. There was also a great deal of discussion amongst London politicians as to whether the solution of Thames flooding was an issue of land drainage, social reforms, or the upkeep of flood defenses. If the poor upkeep of flood defenses were to blame, then the local government would be responsible and need to be reformed. But if the deaths were linked to poverty, since financially insecure people were living in the most vulnerable areas, this would require social reforms instead.

Both the media and Parliament demanded an inquiry, so Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin held a conference to investigate the 1928 London flood, although he focused the event on "flooding, not about London governance or poverty-reduction."

The Technical Sub-Committee investigates

The Conference brought together the Port of London Authority and the Thames Conservancy Board along with local and regional authorities to investigate the causes and implications of the Thames' flooding.

The Conference soon set up a Technical Sub-Committee, which was meant to look into flood surges, investigate flood defenses, and the possibility of establishing a warning system. Although the Technical Sub-Committee agreed with the fact that the 1928 flood was a natural occurrence that was made worse by coinciding natural events, they stated that more research needed to be done to better understand tidal flooding and ensure that flood defenses wouldn't be "unnecessarily expensive," per the University of Manchester.

Although local measures were carried out, such as the creation of the Desborough Cut in 1935 to decrease local flooding, there were no large-scale efforts to suppress flooding around London. Unfortunately, as Gavin Weightman notes in "London's Thames," "nothing was done until the aftermath of the great floods" of 1953.

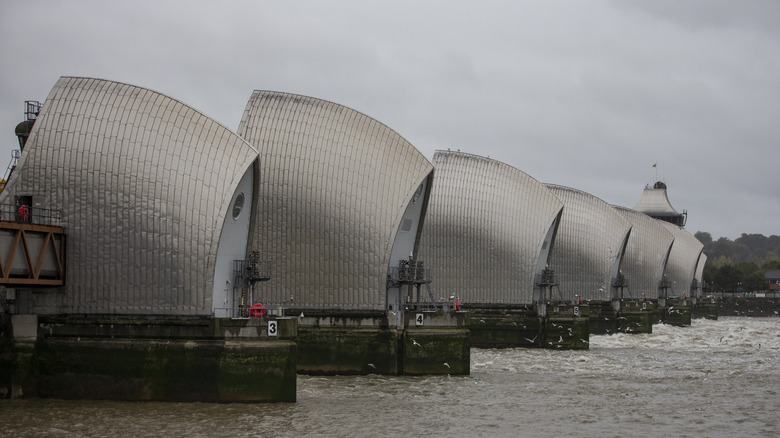

Opening the Thames barrier

London wasn't motivated to invest in the Thames Barrier until the North Sea Flood of 1953. The North Sea Flood, which occurred on January 31 and February 1, 1953, led to "unprecedented" flooding in England and the Netherlands, according to Environment & Society. Over 2,000 people died in the flooding, the majority of whom were in the Netherlands, and more than 500,000 acres were flooded in total. Although London wasn't affected by the 1953 flood, much of eastern England suffered due to the "1,200 beaches of sea defenses" and it became clear that it was only a matter of time before London became the casualty of another tidal surge.

The inquiry led by Viscount Waverley after the 1953 flood made a point of underlining how flooding was going to become more frequent due to climate change. However, although the Netherlands started to build flood defenses right away, according to The Conversation, it took England almost 20 years to begin construction on the Thames Barrier. It wasn't until the Hamburg floods of 1962 that the importance of flood defenses was finally taken seriously and acted upon.

Built between 1975 and 1983, the Thames Barrier spans over 550 yards across the width of the Thames between Greenwich and Woolwich. Featuring a series of steel gates, 61 meters wide and 20 meters tall, the gates are able to close and form a "continuous steel wall facing downriver" in the event of a high tidal surge.

MI5 moves in

After World War I, MI5, the United Kingdom's domestic counterintelligence and security agency, moved its headquarters to Cromwell Road. However, they were only there for a few years before moving to the Thames House in Millbank, according to "The Defence of the Realm" by Christopher M. Andrew. And although MI5 would move their headquarters during the Second World War and the Cold War, by 1995 they were back at their Thames House home.

In "100 Places You Will Never Visit," Daniel Smith writes that MI5's presence in Millbank was possible because of the 1928 London flood. The Millbank area of central London was the most severely affected area and had to be almost completely rebuilt. Previously, the area was considered a "slum" and the destruction caused by the flood cleared the way for "assorted new office and apartment blocks," though it's unclear if the previous residents of the area were offered these new apartments first.

The Thames House, designed by Sir Frank Baines, is a large block of offices that was built upon the demolished remains of Millbank. MI5 claims that at the time it was described as "the finest office building in the British Empire." However, architectural historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner noted his personal dislike of the Thames House's "nasty cheese-colored roof."