The Freedmen's Bureau: What Was It? We Explain

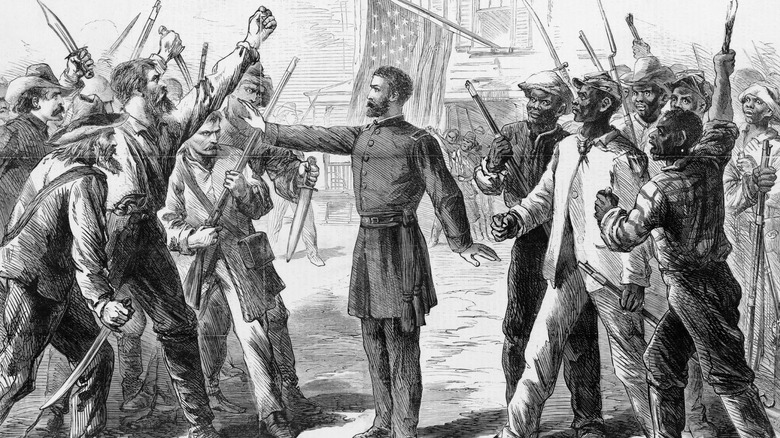

The Freedmen's Bureau was given an unbelievably massive task after the American Civil War ended, and historians continue to question how much of its efforts can be considered a success. In more ways than one, the Freedmen's Bureau fell massively short of its responsibility to formerly enslaved Black Americans. For example, although the Freedmen's Bureau kept the "best records of outrages committed on Blacks by whites," including those in the KKK, there's little evidence to suggest that the Freedmen's Bureau was successful in prosecuting or preventing such incidents.

But considering the complete lack of support that Black people in the South received on a state and local level in the aftermath of the Civil War, perhaps some of the Freedmen's Bureau's efforts shouldn't be discounted, even though these efforts rarely surpassed the bare minimum.

Under-funded and under-staffed, the Freedmen's Bureau was never really given the chance to succeed. But in less than a decade, numerous programs were initiated, including schools, hospitals, and courts. It's impossible to say for sure whether Reconstruction would've been worse without the efforts of the Freedmen's Bureau, but it's unlikely that it would've been better. Here's the complicated history of the Freedmen's Bureau explained.

What was the Freedmen's Bureau?

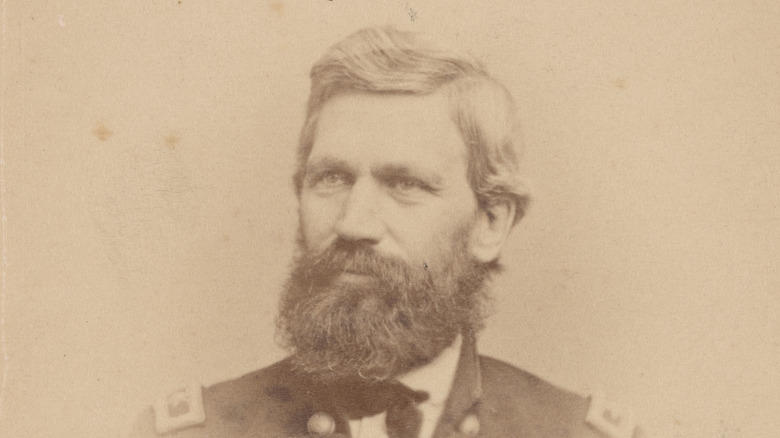

One month before the end of the American Civil War, the United States Congress established the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, also known as the Freedmen's Bureau, on March 3, 1865. According to VCU Libraries, the Freedmen's Bureau was organized under the War Department and Major General Oliver Otis Howard, a Union general during the war, was appointed as commissioner in May. Howard would end up being the only commissioner of the Bureau.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture writes that the Freedmen's Bureau was in charge of helping formerly enslaved people get their bearings after the Civil War. This assistance ranged from providing food and clothing to promoting a system of labor contracts and helping formerly enslaved people reunite with their families, writes the National Archives. And this was no small task. The Bureau was accountable to more than 4 million formerly enslaved Black people in addition to Southern white refugees. But despite these responsibilities, the Freedmen's Bureau was poorly funded. The Bureau received $7 million in 1866, approximately 1% of the $536 million in federal spending that year.

The Freedmen's Bureau was only supposed to operate for one year, but in 1866, Congress passed new legislation to extend the Bureau's lifespan in addition to increasing its powers. Although President Andrew Johnson vetoed this legislation, the bill was "passed over Johnson's veto on July 16, 1866." At its height, the Bureau was present in major cities in 15 states.

Humanitarian efforts

One of the main tasks of the Freedmen's Bureau was to distribute food rations and clothing to those in need. Between 1865 and 1869, it's believed that the Freedmen's Bureau gave out 21 million meals. "Liberty, Equality, Power" writes that in 1865 alone, food rations were issued to 150,000 people daily, "one-third of them to whites."

Although General Howard ordered that food rations should be stopped after October 1, 1866, "except to freedmen and refugees in hospitals and orphan asylums," according to "A History of the Freedmen's Bureau" by George R. Bentley, the Governor of Alabama Robert M. Patton protested that this would lead to starvation and took his complaints to President Johnson himself, who ordered the food rations to continue "in so far as it was absolutely necessary." Howard also stated around 1867 that he "interpret[s] refugees as liberally as possible to prevent starvation."

The Freedmen's Bureau also distributed clothing to Black Americans, stating in the Freedmen's Record that "clothing is their most pressing need, especially for women and children, who cannot wear the cast-off garments of soldiers," per "Battle Scars."

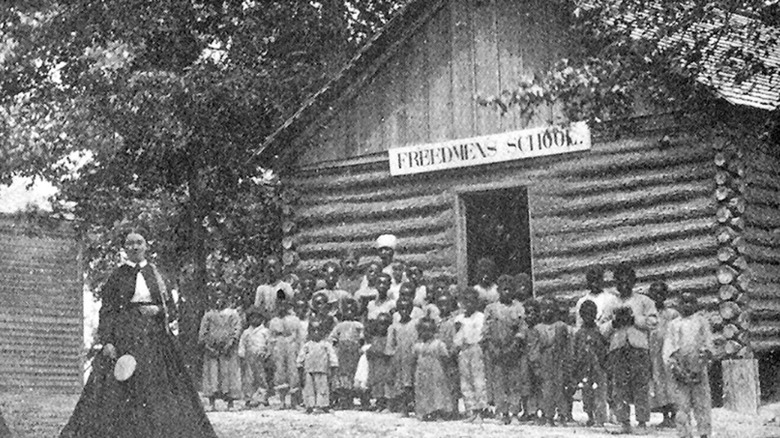

Freedpeople's schools

One of the largest initiatives of the Freedmen's Bureau was the establishment of free schools for Black people. Between 1865 to 1870, the Freedmen's Bureau spent "more than $5 million on schools," and by 1870, over 150,000 Black children were enrolled in school, according to The Atlantic. According to "Poverty and the Government in America," most of the schools were established in unused military buildings and the majority of teachers were white northern women. Ultimately, the Freedmen's Schools "failed to recruit available Black teachers." As a result, most Black children didn't attend these public schools, with parents preferring to enroll their children in private subscription schools with Black teachers, per American Educational History Journal. For those who did end up attending the Freedmen's Schools, many only attended a few months out of the year.

But even with limited attendance, these schools were the "foundation for public school and college education" for Black Americans in the South. Even Howard University was founded by the head of the Freedmen's Bureau.

Schools also ended up becoming a target, Hilary Green writes in "Education Reconstruction." Because "education had previously been used as a means of reinforcing Black Richmonders' lack of freedom and citizenship," those who attended and taught at Freedmen's Schools were harassed for creating the possibility of education for Black Americans. In places like Virginia, "Male teachers endured whippings. Female teachers and students often found themselves pelted by rock throwing white youth while walking the city streets."

Freedpeople's hospitals

The Freedmen's Bureau was also responsible for providing medical aid to newly freed Black Americans. According to "The Racial Divide in American Medicine," in Davis Bend, Mississippi, around 200 to 250 Black people were treated there every month. And by June 1869, it's estimated that doctors working for the bureau had treated over 500,000 people and were operating 60 hospitals and asylums.

However, the federal government was incredibly negligent in response to medical care and repeatedly refused to "provide Bureau doctors with adequate support," according to "Sick from Freedom" by Jim Downs. Downs also notes that rather than assessing the health conditions of freedpeople, inspectors would evaluate "freedpeople's health status within a labor context," often coming to the conclusion that medical aid was unnecessary "as they are generally self-supporting."

As a result, many doctors reached out to benevolent societies for aid. The Colored Benevolent Societies were "of particular support." Even during the smallpox epidemic from 1862 to 1868, leaders of the Medical Division of the Freedmen's Bureau didn't provide doctors in the South with adequate funds for quarantine or vaccination campaigns, expecting instead "the extermination of the Black race." Despite the existence of these hospitals, thousands of Black people would never go to a Freedmen's Bureau doctor or hospital, believing that there would later be "negative consequences for freedpeople to seek federal charity."

Legal aid

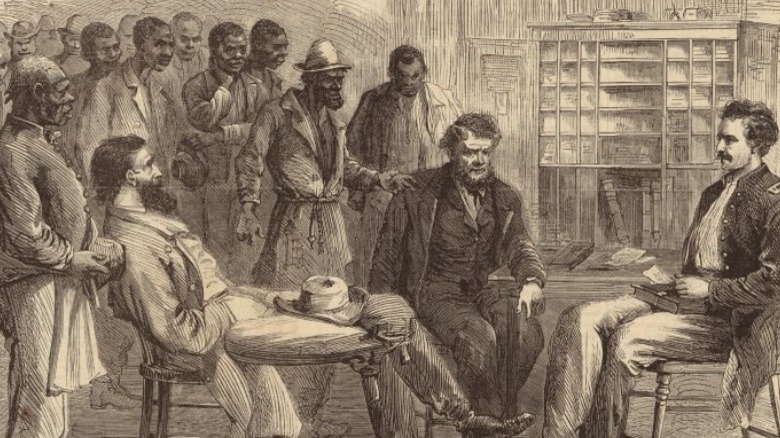

When General Howard first proposed the Freedmen's Bureau courts, he suggested creating a court to deal with labor cases involving less than $200 that would be staffed by a Bureau agent, a representative for Black people, and a representative for the white planters. According to Judicature, Howard predicted that the representative for Black people would be "an intelligent white man who has always been their friend." In practice, Howard instead issued an order that allowed the Freedmen's Bureau to "assume judicial control from the states" in the event that courts continued to refuse Black people the right to give testimony.

The Freedmen's Bureau courts closed most of their own courts after the first few years of Reconstruction, according to "Litigating Across the Color Line," as states passed legislation granting Black people "legal equality and the ability to testify." The Bureau would also provide lawyers to freedpeople who didn't have representation. Unfortunately, these courts offered little actual recourse to Black Americans. Many white people threatened Black people with death if they were found to have reported assault or injustice to a Bureau agent, and for this reason, Black people showed "an utter unwillingness to return to the place they have left." And few were willing to testify as witnesses, having also been threatened.

According to the National Archives, the Bureau was also responsible for issuing marriage certificates to formerly enslaved people, since "slave marriages" were not considered to have "legal standing."

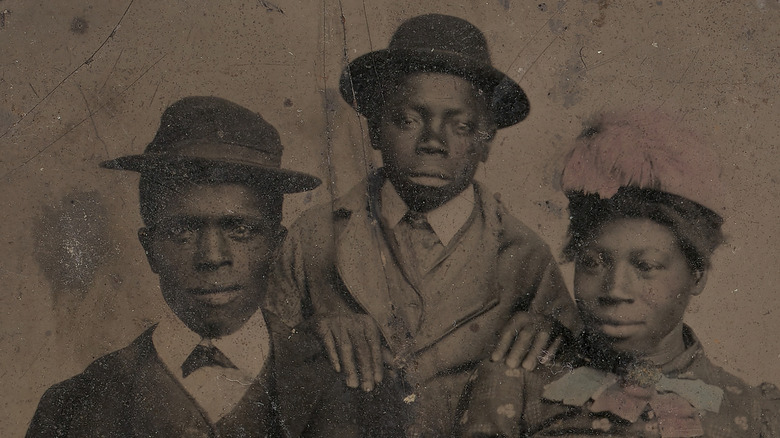

Finding family members

After the American Civil War ended and enslavement was abolished, except as punishment for a crime, thousands of formerly enslaved Black people tried to reunite with their family members, from whom they'd been forcibly separated. According to "Bound in Wedlock" by Tera W. Hunter, "the bureau's first goal was to reunite family members who had been separated."

However, although the Freedmen's Bureau tried to assist with this, they were incredibly unprepared to help with reunification, with little financial resources and "scanty documentation kept by slave traders," writes Slate. The fact that enslavers would also change the names of the people whom they were enslaving also made it incredibly difficult to track down family members.

As a result, freedpeople put out their own advertisements in newspapers. It's unclear exactly whether or not the Freedmen's Bureau assisted with these advertisements in any way, but it's reported that the bureau "provided free transportation to reunite family members" in the event that they were found. But overall, these advertisements were largely an "ad hoc community measure." The advertisements were also read out in church by pastors, allowing for the advertisements to reach a larger audience. One such advertisement read: "BURRELL ROSE (colored) wishes to know the whereabouts of his daughter EMMA ROSE. Her mother was named Tena. She formerly belonged to William Pitman of Buckingham, Virginia, and was carried by William Pitman to Tennessee, near Memphis. Any information of her will be thankfully received and rewarded."

Settling freedmen

As the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, the Freedmen's Bureau was in charge of redistributing abandoned land to "loyal refugees and freedmen." And according to "Constraint of Race" by Linda Faye Williams, this is "where the Bureau failed most tragically." The Bureau was given the power to lease abandoned properties and after three years, whoever was leasing the land could purchase it from the Bureau. And by 1865, the Bureau had over 850,000 acres of abandoned and confiscated land to redistribute.

Although the Freedmen's Bureau leased and allowed the settlement of almost 500,000 acres by mid-1865, President Johnson and his administration fought back against this redistribution, and the Freedmen's Bureau was subsequently forced to undo all the resettlement that had occurred. In "A History of the Freedmen's Bureau," Bentley writes that in Johnson's revision of the Bureau's order, confiscated property only applied to "property already sold under a court decree." General Howard was also required to restore lands to pardoned rebels. This effectively "not only cut off prospects for Black landownership but also returned to the planters the land of the few freedmen who had cobbled together the means to plant crops on their leased lands in 1865," Williams writes.

At the end of the day, the Freedmen's Bureau retained around 75,000 acres to lease to Black people. And those who refused to work for the planters, to whom control of the land had reverted back to, were evicted.

System of labor contracts

In light of the failure of the land lease program, the Freedmen's Bureau came up with a labor system instead and encouraged Black people to sign labor contracts. However, the "free-labor contract system" ended up resulting in almost as many abuses as had occurred during enslavement. Saidiya V. Hartman writes in "Scenes of Subjection" that the labor contracts facilitated by the Freedmen's Bureau "were used primarily to regulate freedmen's behavior rather than to establish the tasks to be performed."

Although Freedmen's Bureau agents helped formerly enslaved people negotiate their labor contracts, many of these contracts were "little more than slavery under another name." In at least one instance, a group of Black people in South Carolina who refused to sign a "contract for life" were evicted and murdered.

But with the institution of the Black Codes in the South, many formerly enslaved people had few other options than the labor contracts. According to The History Engine, Bureau officials were generally more concerned about making sure that contracts were signed and that plantations had labor rather than ensuring that Black workers were protected from exploitation. And Bentley notes in "A History of the Freedmen's Bureau" that Bureau officials frequently failed to ensure that white planters were paying Black workers a fair wage. On the rare instance that a white planter was found guilty of exploiting Black workers, it's reported that he could be "heavily fined or incarcerated," although there's little evidence that this was a regular occurrence.

Varying effectiveness

Overall, the lack of enforcement and lack of funding, sometimes but not always related, affected the efficacy of the Freedmen's Bureau. At its peak, it employed no more than 900 people, "with some 300 of these serving as clerks rather than agents," and during its 7-year lifetime, less than 2,500 people total were Freedmen's Bureau agents.

The effectiveness of the Bureau also varied depending on the state. Mary Farmer-Kaiser notes in "Freedwomen and the Freedmen's Bureau" that in Mississippi, there were only 12 agents in 1866, and in Alabama, there were no more than 20 throughout the Bureau's life. In "Poor But Proud," Wayne Flynt writes that in the state of Alabama, the Freedmen's Bureau "helped far more of Alabama's poor whites than Blacks." This was largely because General Howard "interpreted 'refugees' broadly to include virtually any indigent whites," since the Freedmen's Bureau was designed to assist "destitute freedmen and refugees."

By 1867, "many local and federal Bureau officers [also] grew increasingly intolerant of freedpeople's needs and repeatedly denied them assistance," according to "Sick from Freedom" by Jim Downs. W. E. B. Du Bois would later write that the successes of the Freedmen's Bureau "were the result of hard work, supplemented by the aid of philanthropists and the eager striving of Black men. Its failures were the result of bad local agents, the inherent difficulties of the work, and national neglect."

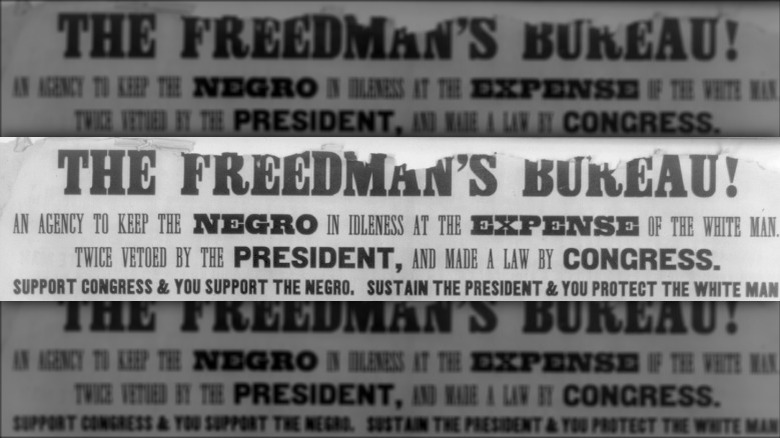

Perception towards Freedmen's Bureau

Although many white people who lived in the south "viewed the Freedmen's Bureau with hostility," some acknowledged, albeit "privately," that the Bureau was helping prevent further devastation in the aftermath of the Civil War. But overall, there was great resistance among white Southerners to the work of the Freedmen's Bureau. Brandi Clay Brimmer writes in "Claiming Union Widowhood" that freedpeople's schoolhouses and teachers were frequently threatened with violence and on at least one occasion, a freedpeople's schoolhouse was set on fire by white people in Clinton, Tennessee. Bureau offices were also "targets for racist violence."

According to Willie Lee Rose, white Southerners "resented the Bureau as a symbol of Confederate defeat and a barrier to the authority reminiscent of slavery that planters hoped to impose upon the freedmen," per "The Freedmen's Bureau and Black Texans." And "Freedwomen and the Freedmen's Bureau" writes that some officials "blatantly chose to become instruments of the old planter class." For example, at the Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony, Bureau agents actively tried to displace the Black people who'd settled on the land. "In particular, they further contracted rations and restored the colony's land to the white owners."

As a result, few formerly enslaved people saw good reasons to trust the Freedmen's Bureau. And even when they did, the result varied greatly. According to The Chicago Reporter, the failure of the Freedmen's Bank, with little-to-no reimbursement from the bank or the federal government, also fostered a distrust of savings banks.

Fall of the Freedmen's Bureau

All in all, although the Freedmen's Bureau lasted less than a decade, it was "a social relief program of unprecedented scope." And while the Bureau oversaw some successes, like the establishment of over 1,000 schools for Black students, it was also responsible for numerous failures, such as the staffing of these schools with white teachers and the inability to secure land for freedpeople, writes VCU Libraries.

According to "The Voting Rights War" by Gloria J. Browne-Marshall, shortly before the Freedmen's Bureau finally closed, General Howard was dismissed as its president and the Bureau's budget was cut in half. After that, it was only a matter of time before the Bureau was shuttered. By 1869, the work of the Freedmen's Bureau was already limited to education and schools only.

The Freedmen's Bureau finally closed in 1872, "under pressure from conservative southerners." The Equal Justice Initiative writes that despite the federal effort put into the Freedmen's Bureau, it was ultimately undermined by "the inadequate and incomplete commitment" to supporting and protecting formerly enslaved people. As a result, white supremacist resistance was also able to effectively hinder any large-scale attempts at societal change by the Freedmen's Bureau.