The Untold Truth Of Doctors Without Borders

Doctors Without Borders, often known after the French acronym MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières), established a new practice in humanitarian action. Outside intervention, the essence of humanitarian help, is always problematic in conflict zones, especially the part of defending the vulnerable against the oppressor. It means taking sides, which many humanitarian organizations refuse to do, since it would affect the dispute and they are bound to neutrality.

But Doctors Without Borders decided to commit to providing help to those who need it, regardless of possible political complications. This led to several situations where the organization was banned from the country or the area, or sometimes even trapped in the conflict itself, as in case of the Rwandan genocide. The organization is also known for their strong opinion against pharmaceutical companies, trying to bring down the prices of drugs and medicine equipment. Given that, Doctors Without Borders received the Peace Nobel Prize in 1999 for their uncompromising humanitarian efforts (via Britannica), but also their role in peacekeeping operations. Their work across 70 countries has been crucial for survival of many displaced, war-stricken, and impoverished communities.

This is the untold truth of Doctors Without Borders.

Doctors Without Borders received the Nobel Prize for Peace

While the Nobel Prize is usually awarded to individuals, some organizations have received this honor as well. One of them is Doctors Without Borders, as reported by The New York Times. The organization was recognised by the Norwegian Nobel Committee in 1999 for its readiness to send forces to crisis points all across the world, despite possible political complications.

It was this intentional disregard of usual diplomacy, which mostly serves those who are in power, which convinced the committee to honor the organization with the Nobel Peace Prize: "In critical situations marked by violence and brutality, the humanitarian world of Doctors Without Borders enables the organization to create openings for contacts between the opposed parties ... At the same time, each fearless and self-sacrificing helper shows each victim a human face, stands for respect for that person's dignity, and is a source of hope for peace and reconciliation." Along this, the organization helped to bring attention to different humanitarian problems, which could otherwise stay overlooked.

Doctors Without Borders was never neutral

Doctors Without Borders was born out of dissatisfaction with the humanitarian work existing at that point. In the late 1960's, doctors Max Recamier and Pascal Greletty-Bosviel frequently collaborated with the Genevan International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) on their interventions in war zones. A team consisting of six people — two doctors, two clinicians, and two nurses — traveled to Biafra, Nigeria, which was torn apart by the civil war at the time. They started to speak up about the horrific realities of the conflict, criticizing the Nigerian government and the Red Cross on the way.

The Biafrans, as the group was called at the time, approached humanitarian aid from a different perspective: by putting the victims first, instead of political (or other) ideologies, they resisted the prevailing narrative of altruistic, but silent, witness. So when two medical journalists, Raymond Borel and Philippe Bernier, shared their idea of a medical organization, which would work across borders, the Biafrans were already doing it. By connecting the two groups, Doctors Without Borders was born in 1971: "We wanted to ensure sufficient knowledge of this new type of medicine: war surgery, triage medicine, public health, education, et cetera. It's simple really: go where the patients are. It seems obvious, but at the time it was a revolutionary concept because borders got in the way. It's no coincidence that we called it 'Médecins Sans Frontières,'" explained Bernard Kouchner, one of the founders (via Doctors Without Borders).

The organization was expelled from several countries

Due to their outspokenness, Doctors Without Borders found themselves in several conflicts with the authorities, often resulting in them being expelled from a country.

In 2014, the organization became a problem for the Myanmar government, which resulted in official forbiddance of all their activities in Rakhine State, reports Tim Hume for CNN. This came after the government accused the organization of bias towards the Rohingya minority, by implanting conflicts in local communities: "When they give treatment to people they prefer to emphasize on the Bengali people. Sometimes Rakhine people visit their clinic seeking help and they're refused. They allow transportation of Bengali patients to the nearby hospital, but they fail to provide the same service to the Rakhine people," explained But Ye Htut, the spokesperson for Myanmar President Thein Sein. Many citizens protested against their presence in the area. Another issue was the truth about the Maungdaw massacre, where Doctors Without Borders reported a much higher number of victims than the authorities.

Another situation took place in Ethiopia in August 2021. The Ethiopian government accused the organization of having a devastating effect on the conflict in Tigray region. Redwan Hussein, government delegate, insinuated that the organization could be linked to arms trafficking, helping the opponents of the current administration, reports AP (via VOA News). Doctors Without Borders was suspended for three months, with the authorities blocking the delivery of the emergency aid to the war zone in Tigray.

Doctors Without Borders is facing accusations of institutional racism

The idea of Western humanitarian help in developing countries is built on a thin ice and full of prejudice and colonialist mentality, explains Christos Christou, the international board president of Doctors Without Borders, to Nurith Aizenman for NPR: "It's this idea of the white savior — the white doctor going and providing assistance to the people in Africa and especially to little African kids." The organization is going through an internal transformation of reinventing the humanitarian standard, but, with the complexity of the problem of racism, the end goal is nowhere near.

These changes are slow, and while the percentage of those who fill the leadership positions and don't come from the Western world has risen, there is still the problem of pay gaps between the local and international staff. As disclosed by Dr. Indira Govender for Reveal News, her experience with the organization in 2014 — when she worked in Sierra Leone during the Ebola outbreak — was anything but pleasant. Faced with personal and systematic racism, the organization was clearly led by the white expats, not the local people. The disconnect between the two groups was obvious, and Govender felt people were excluded only on the basis of racial prejudice.

Sometimes, the organisation is caught in violence

There is nothing which could erase the Rwandan genocide that took place right in front of the eyes of the international public in 1994. While the violence of the Hutu government shocked many, no one intervened, resulting in over 800,000 deaths in 100 days, mostly of members of the Tutsi minority.

Being present in Rwanda since 1982, Doctors Without Borders had a wide network of mobile hospitals and branches all over the country, while also employing many local medical staff, members of both ethnic groups — Hutu and Tutsi. Despite the danger, the organization did not leave the country, not only providing medical treatment, but also safety from the aggressors.

This made them an easy target, with more than 200 Doctors Without Borders staff killed between 1994 and 1997. Because the organization employed both ethnic groups — Tutsi and Hutu people — they were not excluded from the bloodshed. With the Hutu authorities targeting Tutsi people, Tutsi staff was subjected to the same treatment. In some cases, Hutu staff members were forced to murder Tutsi co-workers in exchange for their own lives. When the organization tried to evacuate their staff from the war zones, they were stopped by the authorities, preventing Tutsi people from leaving, while medical facilities were destroyed and patients killed. But Doctors Without Borders did not give up, pleading with the international community, including the UN Security Council and the French government, to stop the conflict (via Doctors Without Borders).

Doctors Without Borders is fighting global pharmaceutical companies

The organization was always open regarding their position towards pharmaceutical companies: medicine is for people, not for profit. The reality is much different, and Doctors Without Borders found itself in several conflicts with international companies over the years.

As reported by James Hamblin for The Atlantic, the organization rejected a million vaccine doses donated by Pfizer in 2016, with the argument that they don't want to support the patent and overpricing practices frequent in the vaccine business. Specifically, behind Pfizer's generosity lies a much darker reality — although the patents of the specific drugs and vaccines could be easily shared, the company is refusing to do it, or, at least, to lower the price. For example, the costs of the PCV13 pneumonia vaccine by Pfizer, Prevnar 13, are too high. Doctors Without Borders cannot always provide it to patients in areas most affected by pneumonia — subsaharan Africa and southeast Asia — despite their numerous attempts in the past. The donation of million doses is only a drop in the sea, and by refusing the donation, Doctors Without Borders made a stand against the hypocrisy of the industry.

In 2021, in the midst of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, Doctors Without Borders made another appeal, this time to both Moderna and Pfizer. Since Moderna used public money to develop the COVID-19 vaccine — and projected to make $18 billion in profits in 2021 alone (via Doctors Without Borders) — the organization is urging both companies to share their patents across the world, not only in those countries that they can afford it (via Doctors Without Borders).

The organization has a longstanding conflict with the U.S. government

When it comes to costs of pharmaceutical drugs in the USA – the country with the highest medical bills in the world — the U.S. government plays a major factor in this equation. As explained in the Huffington Post, the Obama administration did everything in its power to stop developing countries from getting access to generic versions of medications. Doctors Without Borders has been trying to push to change this for years, but so far, without success. When India developed a generic version of HIV medication, the Obama administration blacklisted the country, while continuing to force India to use the expensive American drugs: "India's patent laws and policies have fostered robust generic competition over the past decade, which has brought the price of medicines down substantially — in the case of HIV, by more than 90 percent. The world can't afford to see India's pharmacy shut down by U.S. commercial interests," emphasized Doctors Without Borders director of policy Rohit Malpani.

In the midst of the global health crisis in 2022, Doctors Without Borders made several public appeals to the Biden administration, demanding that he reveal the costs of clinical trials. Pharmaceutical companies frequently justify the high costs of their products by stating that the real reason behind those prices are the high costs of clinical trials, but these costs remain a secret — at least to the public. By making this information available, the final prices of products could be justified (via Doctors Without Borders).

One doesn't need to be a doctor to join Doctors Without Borders

The organization operates in over 70 countries, managing around 45,000 staff all across the world. Since the medical support needs a lot of logistics, one doesn't need a medical degree to be able to join the team — just a bit of time, since assignments last from six to 12 months in total. Finance specialists, engineers, logisticians, and other project managers are welcome, as long as they can handle working under pressure (via Doctors Without Borders).

For those who want to join Doctors Without Borders, the recruitment period can last from three to six months. First, the applicant needs to fill in an online form and write a letter of motivation. The second step is a technical test, followed by an interview, after which it is decided whether the candidate is accepted or not. In the case of a positive response, the applicant will undergo different training and learn more about how the organization works (via Doctors Without Borders). When a volunteer finishes preparation, and is matched with a specific field position, they're ready to go!

The organization is looking for people who can show great flexibility and ability to improvise. They must also be team players, welcoming to different cultures, and, above all, they must handle stress well: "As professionals working on assignment with MSF, most of us understand the challenges we will face in our work, but I was unprepared for the level of stress the job entails," admitted Aniela Markowiez, deputy HR coordinator in Lebanon (via Doctors Without Borders).

Doctors Without Borders educates women on how to practice self-care

Following the WHO's guidelines on self-care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights published in 2019, Doctors Without Borders developed more programs with the aforementioned focus. The goal of the initiative is to improve women's ability to improve their own health and the health of their families, along with strengthening autonomy regarding their bodies and lives.

Self-care involves examination, diagnosis, testing, and medication, but also gaining knowledge and making informed decisions. Self-care should not replace adequate healthcare, but the reality is, especially in areas affected by conflict and poverty, self-care is sometimes the only option women have. It also widens the effect of healthcare resources and covers locations with poor medical infrastructure.

There are several ways Doctors Without Borders help to promote self-care. Women in Zimbabwe were taught how to self-swab for human papillomavirus infection tests in 2021, which enables more women to discover the possible early stages of cervical cancer. Another program for sex workers was run in Malawi between 2014 and 2020 with the goal of reducing the prevalence of HIV and tuberculosis in women. Due to high levels of gender violence which Malawi's sex workers are exposed to, they suffer from a high number of health issues. The program included self-testing for HIV, pregnancy prevention, and access to information and community support. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, women were introduced to an injectable contraceptive method, which allows them to stay protected for a year, even without visiting a doctor (via Doctors Without Borders).

Doctors Without Borders worked in almost 70 countries across the world

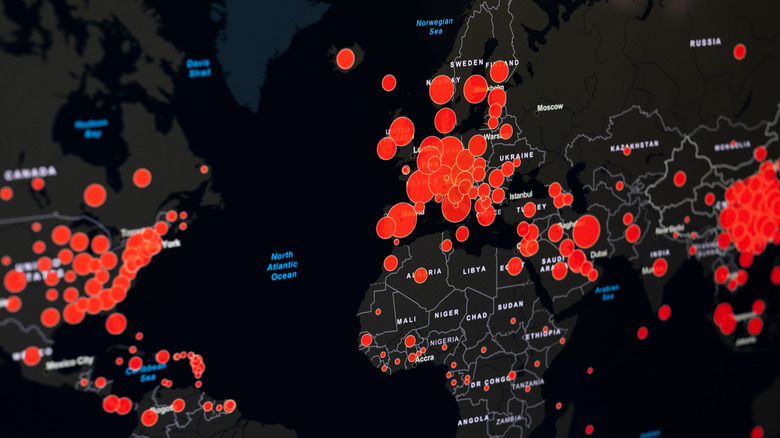

The sheer magnitude of the work Doctor Without Borders is doing is almost incomprehensible, revealing the horrible situation of global health. Working across different continents and countries, the U.S. branch of Doctors Without Borders conducted almost 10 million patient consultations, admitted 877,300 patients to hospitals, and distributed a million doses of vaccinations against measles across the globe.

As shown in the 2020 report, the global pandemic limited most of the progress Doctors Without Borders made in the recent years, only exacerbating conflicts, poverty, and the general situation of health care across the world. Regardless of that, the organization continued with their efforts in the prevention and treatment of HIV, tuberculosis, and hepatitis C. They filled the gaps in healthcare in Iraq and Pakistan, but also provided basic assistance to the vulnerable affected by COVID-19 restrictions in Hong Kong. In South Africa, Haiti, and Yemen, Doctors Without Borders ran the only COVID-19 hospitals in the areas, helping patients with severe symptoms.

But, during 2020, Doctors Without Borders worked in countries which wouldn't normally find themselves on the list of those who need help. Vulnerable people in France, Spain, Belgium, Switzerland, and the U.S. needed help throughout the pandemic, as, in many cases, people were left without any support (via Doctors Without Borders).

There is also Homeopaths Without Borders

The organization is established on the homeopathic belief that the body is able to cure itself, with the help of natural substances diluted in water. The idea behind the volunteer-based organization is the same as with Doctors Without Borders: sharing knowledge and medication in those countries that need it. Homeopaths Without Borders works on different projects in Haiti, Cuba, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Sri Lanka, and others, generally serving communities across North America (via Homeopaths Without Borders)

But, as there is a lot of controversy around homeopathic treatment, there are several people who oppose such endeavors. Since the principles of homeopathy do not match with the current scientific ideas and standards, homeopathy was declared a myth by numerous studies. Despite its widespread use in Germany and France, the ongoing battle against homeopathy is proving to be successful, with France removing the homeopathic medicine from the list of the drugs covered by health insurance. On the basis of this argument, in The BMJ, David M. Shaw criticizes Homeopaths Without Borders, claiming their work is harmful and misleading.

Several other similar organizations exist, too, such as Naturopaths Without Borders, Herbalists Without Borders, and Aromatherapists Without Borders, reports BBC.