The Untold Truth Behind The 1982 Boston Arson Spree

In the 1980s, the city of Boston, Massachusetts was in the grip of an arson spree that resulted in over 200 fires in a few years. Nor was this the first time that the city was overcome with flames.

In 1977, Boston was swept up by another arson spree, with almost 100 buildings going up in flames (per The New York Times). But while those fires were lit in an attempt to collect insurance premiums, the arson spree of the 1980s was a little more personal.

The arson spree in Boston during the 1980s wasn't done out of a desire for insurance fraud. Instead, the arsonists, mostly a group of Boston firefighters and police officers, was led by somewhat contradictory motives, but ultimately driven by vengeance.

The group responsible for the arson spree set dozens of fires, and on one occasion set seven fires in a single night. The group was also incredibly brazen, using a car that looked like a police cruiser with a vanity plate that said "Arson," so that "anyone who saw them thought they were operating in the area as investigators or public officials," per Charlestown Patriot Bridge. But what exactly caused this arson ring to commit what's considered to be the largest arson scandal in United States history?

Budget cuts in Boston

In 1980, voters in Massachusetts voted to pass Proposition 2½, which placed a 2.5% limit on the amount of revenue that communities can raise through property taxes, known as the property tax levy. According to the Massachusetts Department of Revenue, "the property tax levy is the largest source of revenue for most cities and towns" in Massachusetts, and is used to help fund a number of local services like schools and public safety. Proposition 2½ was set to go into effect in July 1981 and, according to United Press International, it was estimated that roughly 650 police officers and 550 firefighters were going to be laid off as a result of the budget cuts.

Massachusetts had a "last-hired, first-fired scheme for civil service layoffs," which would have resulted in a majority of non-white people being dismissed since (per The New York Times) "court-ordered diversification" accounted for the most recent hires. Initially, this first-firing scheme was limited by the U.S. District Court because it would "reduce the percentage of minority police officers and firefighters below the level obtained before the layoffs began."

However, after this court decision was upheld by the Court of Appeals in 1982, Massachusetts enacted new legislation to provide Boston with more funding, "requiring it to reinstate all police officers and firefighters laid off during the city's fiscal crisis, and security those persons against future layoffs for fiscal reasons," writes "United States Reports." With the new legislation, the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the judgment of the Appeals court.

An arson spree

Despite the fact that all police and firefighters were to be eventually reinstated, a group of eight people, which included Boston police officers and firefighters, decided to take matters into their own hands by starting an arson spree in Boston. The arson spree is believed to have lasted at least 10-14 months, starting in late 1981 after the budget cuts went into effect. Some sources say the fires lasted through 1984. Most of the fires were set using "La Bomba," which was a time-delay incendiary device.

According to the Associated Press, the group of arsonists set over 260 fires in eastern Massachusetts with the mistaken belief that an increase in fires would lead to more firefighters being hired. But although this was the primary motive behind the arson ring, United Press International writes that "some of the fires were also set for profit and revenge." Donald Stackpole, one of the members of the arson ring, wasn't interested in trying to get firefighters their funding back or even trying to earn a profit. According to Justia, Stackpole "thought firefighters were overpaid and underworked and merely wanted to harass them." The building of the Boston Sparks Association was also torched because two members of the arson ring were denied membership (per WCVB). U.S. District Judge Rya Zobel described the fires as occurring "at an incredible and never-before-experienced rate."

The arson capital of the U.S.

The wave of fires in Boston was so intense that national media started referring to the city as the "arson capital of the world." With the number of fires involved, it became known as "the largest single arson case in history, state or Federal, in terms of the number of fires involved," according to The New York Times. The fires also ended up causing up to $22 million worth of destruction of property.

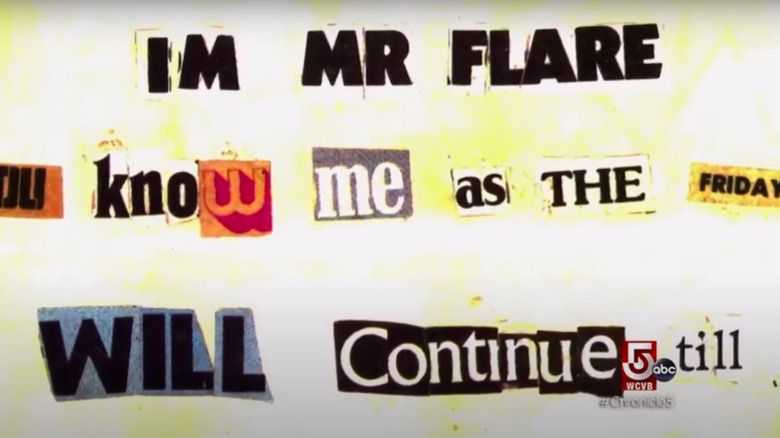

The Boston Globe writes that at one point, one of the arsonists sent a letter to a local television station that read, "I'm Mr. Flare. You know me as the Friday firebug. I will continue till all deactivated police and fire equipment is brought back," in quintessential ransom note fashion with each letter cut from a different publication.

Per Justia, most of the fires were set in "metal trash bins and vacant buildings," including houses, churches, factories, a lumber yard, and even the Massachusetts Fire Academy, ironically. According to Boston Fire Historical Society, most of the fires occurred in neighborhoods like Dorchester, Roxbury, Jamaica Plain, and South Boston, which are also neighborhoods in Boston with a predominantly non-white population.

The New York Times also reported that there were several fires in nine surrounding cities and towns that were designed to throw investigators off the trail. Fire alarm boxes were stolen from the arson sites, reports United Press International, so that by the time the fire department arrived, the blaze was already huge (as seen on YouTube).

How many were injured?

In total, almost 300 firefighters were injured due to the fires started during the arson spree. While nobody as a result of the fires, dozens ended up with severe injuries, writes United Press International. During one fire at a military barracks, the roof collapsed onto 22 firefighters. As a result, The Washington Post reports, two firefighters from the military barracks fire ended up with permanent disabilities.

U.S. District Judge Zobel reportedly said during the sentencing that "these were either acts of terrorism or sheer malice, [though] I don't know which." According to former ATF special agent Wayne M. Miller, who wrote the book "Burn Boston Burn" about the arson ring (per The Boston Globe), there was little consideration among the group about the people who were getting hurt. "It became an absolute game of cat and mouse. They were having fun." Associated Press writes that members of the arson ring even "cheered as they watched buildings burn."

The arson trials

In 1984, Robert Grabluski, a Boston police officer, was the first to be arrested. The police didn't have enough evidence to arrest him for arson, but they'd noticed him around the fires and after bringing him in on charges "relating to stolen car parts," they started asking him about the string of arson, WCVB reports. Grabluski eventually confessed, which led to the arrests of Donald Stackpole, Gregg M. Bemis, Wayne S. Sanden, Ray J. Norton Jr., Joseph M. Gorman, Leonard A. Kendall Jr., and Christopher R. Damon. In addition to police officers and firefighters, the group included an Air Force enlistee. The New York Times reports that when the 83-count Federal indictment was announced, it was believed to be "the largest single-arson case in history, state, or Federal, in terms of the number of fires involved."

Grabluski pleaded guilty and was given state and federal prison terms. Associated Press writes that at least three others also pleaded guilty. Stackpole, who was considered the leader, was convicted and sentenced to 40 years in federal prison. Stackpole also pleaded guilty in Suffolk Superior Court and was sentenced to 20 years in state prison as well. For the rest of the group, sentences ranged between five to 40 years. The final conviction was handed down in 1985, finally bringing an end to the Boston arson spree.

Legacy of the arson spree

After the end of the arson spree, the number of fires in Boston dropped substantially, writes the Boston Fire Historical Society. Instead of a single night with up to four major arson fires, Boston dealt with up to four fires in a single year by the end of the 1980s.

Former ATF special agent Miller, who worked on the Boston arson case, believes that such an arson ring couldn't happen in the 21st century. "First of all, there are not that many vacant buildings anymore in Boston because real estate prices are so high. Also, back then we had no cell phones, no GPS or surveillance cameras all over. Plus, fire investigation has come a long way since then and is more sophisticated," per Charlestown Patriot Bridge.

Even if an arson spree of this magnitude is unlikely to reoccur, the damage done by the 1980s Boston arson cases is incalculable. During one of the sentencings, U.S. District Judge Rya Zobel noted that "the consequences of the fires are, I'm not sure even now, fully tallied," Associated Press reports.