Who Was The Man Who Saved Nearly 700 Children During The Holocaust

The more time someone spends learning about the Holocaust, the more horrible things they'll uncover. If there's any chapter in human history that seems to see an infinite number of evils visited upon the world, it's that one — and here's a statistic that no one should ever forget. Exact death tolls are, of course, tricky, but according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, it was the Jewish children of Europe who were particularly vulnerable to the horrors of the Third Reich. By the time war was over, there were only between 6 and 11% of pre-war Jewish children left alive.

Many survived because they were sheltered by families who gave them entirely new identities: Forced to learn new names, languages, and cultures in order to survive, the fate of these children relied on them not revealing who they really were. Others were forced to live on their own, going into hiding and growing up very, very quickly. Families were separated, and for many, those goodbyes were their last.

Some survived because of adults who intervened on their behalf. In addition to the Gentile families who risked everything to save the child or two they brought into their homes, there were people like Nicholas Winton. He was a perfectly ordinary stockbroker, living in London in the late 1930s. To the 669 children he saved — and their thousands of descendants — he was nothing short of extraordinary.

Who was Nicholas Winton?

Nicholas Winton's parents weren't always called Rudolf and Barbara Winton, says Biography: German Jews, they changed their name from Wertheimer with their conversion to Christianity. Their son came along in 1909, born in London into the sort of wealth that gave him a childhood spent mostly in their 20-room, West Hampstead mansion.

For a while, Nicholas Winton lived a perfectly ordinary — if not exceptionally privileged — life. When it came time to choose a career path, he followed his father into the world of international banking. He held positions in the firms of Paris, Berlin, and London, he ultimately settled into the life of a stockbroker at the London Stock Exchange, and he was set to go to the 1938 Olympics as a part of the British fencing team. (As an interesting side note, here's how serious he was about fencing: According to Eastern Region Fencing, Winton and his brother, Robert, established their own fencing competition in 1950. It's called the Winton Cup series, and it continues to be held today in their honor.)

It was also about that time that — according to the Royal Borough of Windsor & Maidenhead, his later home — he got involved with local politics and left-wing, anti-Nazi coalitions. The New York Times says that thanks to his extensive travels, he was fluent in both French and German by this time, and it was about to come in handy.

The phone call — and trip — that changed everything

The Christmas holiday of 1938 was set up to be like any other Christmas holiday. Winton — along with a friend named Martin Blake — was scheduled to chaperone a group of kids from a local school on a skiing holiday. There's a saying about the best laid plans, though, and Winton's plans definitely changed when he got a phone call from Blake (via the Sir Nicholas Winton Memorial Trust). Blake, it turned out, was not anywhere near London. He was in Prague (pictured, circa 1938) — and he told Winton that he needed to get there ASAP.

Winton canceled the trip and headed to Prague. He got there right at New Year's, and what he found was the definition of overwhelming. Blake had gotten involved with the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia, and they were scrambling to evacuate anyone who was at risk of being targeted by Hitler for untimely death or disappearance. The city was filled with refugee camps, and those, in turn, were filled with families in desperate situations. Aid agencies and their volunteers were vastly overwhelmed, and in spite of doing the best that they could, there were still people who were being overlooked.

Winton went to the head of the BCRC, Doreen Warriner. He told her that he wanted to do something to help the children that didn't fall within the guidelines set up by the agencies, and she told him to go ahead.

Taking inspiration from Britain's Kindertransport

Organizing the movement of unaccompanied child refugees across Europe was a daunting task, and according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Winton took a page out of the book of other aid agencies. These agencies were set up to move Austrian and German children to safety, so he knew he needed a similar agency for the children of Czechoslovakia.

Within weeks, he had set up a Children's Section of the BCRC and ran the whole thing out of his hotel. Parents submitted applications to have their children considered for evacuation, and according to The New York Times, it was a dangerous time. Lines of parents got the attention of the Gestapo, and Nazi spies had him under constant surveillance, but he kept going — and soon registered 900 children in need of aid.

Leaving the operation in the hands of two friends — Trevor Chadwick (left) and Bill Barazetti (right) — Winton headed back to England to prepare for the arrival of hundreds of refugee children. The Home Office had approved the whole thing, with some massive stipulations: Each child needed to have a foster home and a monetary guarantee in place before they could leave their homeland (via the Sir Nicholas Winton Memorial Trust). He took out ads appealing for foster homes, he raised money, and when financial support came up short, he donated his own money. By then, time was running short, too: So he started forging paperwork when the Home Office took too long.

The escape route

Children traveled from Prague to London, and it wasn't a simple task. The route was wildly dangerous, and according to the BBC, it went right through Cologne ... and the heart of Nazi Germany. According to The Times of Israel, getting the children through seemingly countless checkpoints and bureaucratic nonsense — which could have seen them sent back to Germany and ultimately killed — required not just an obscene amount of paperwork, but an equally obscene number of bribes. Among those paid to look the other way was the head of the Gestapo for the area, a man named Karl Bomelburg.

For many of the children who made the journey, it's not something they want to remember. When Hanna Slome talked to The New York Times in 2015, the then 90-year-old recalled how she was 14 when she boarded the train with promises from her mother that it was only temporary. She never saw her again, and later learned that after she was killed in a concentration camp, her father committed suicide. She said: "I had never talked much about my rescue, and I didn't want to relive that part of my life."

Paul Salz, then 91, talked a bit about his memories of the journey. He had been given 10 Marks for the entire trip, and it was seized by Germans who searched their luggage. In 1940, he was reunited with his parents in America.

Welcomed to their new homes

The last stop on the journey was London's Liverpool Street Station — and according to The New York Times, Nicholas Winton was there to meet each of the trains. The first one had left on March 14, 1939 — the day before the German invasion. At the other end, 20 children — carrying one little bag and wearing a name tag — disembarked to meet Winton and their host families.

According to the Sir Nicholas Winton Memorial Trust, families across the country had answered the call to host the children, and had driven down to London to meet them as they got off the train. That wasn't the last they heard from Winton and his office, though, as they kept in constant contact with their foster families and children, offering whatever support they could.

Once in England, their experiences were varied (via The New York Times). Ernst Steiner — the only one of four siblings who made it onto the transport — lived in a Jewish-run children's home. Peter Henry Sprinzels was one of the lucky few, and was reunited with his father upon his arrival in England. Emma Speed spent five years with her Nottingham foster family, and brothers Hanus and Karl Gross were sent to a series of farming camps.

The end of his war work

After the German invasion of Prague, the organization's work got a lot more difficult. Eight transports ultimately left Prague, carrying 669 children to safety. When things went sideways, they went sideways very, very quickly. According to the Sir Nicholas Winton Memorial Trust, close scrutiny from the Gestapo meant that they were all in danger of suffering the same fate they were trying to save people from. Tragically, their work went unfinished.

There was a ninth transport: It was the largest to date, and 250 children had been scheduled to leave on it. As the departure day — September 1 — approached, the situation was getting more and more uncertain. Then, on that day, the borders were closed, and the trip was canceled. It's not known for sure what happened to those 250 children, but it's believed they were sent to the Terezin and Auschwitz concentration camps, where they were killed.

Winton had organized the rescue of 669 children, but for him, it hadn't been enough. According to The Guardian, he had always regretted not being able to save more. When he'd returned to England in order to book foster families and raise money for the refugee children, he hadn't just asked England's Home Office. He had gone to other countries — including Australia and the U.S. — for help and had been refused. He said: "If Americans had only agreed to take them too, I could have saved at least 2,000 more."

Post-Kindertransport war years

The Sir Nicholas Winton Memorial Trust says that after the transportation of child refugees came to an end, he continued to contribute to the war effort. Britain declared war just a few days after the last transport became trapped in Nazi-occupied territory, and that meant the war was truly just beginning.

Originally finding work at the Hampstead Air Raid Precautions depot, he eventually ended up volunteering to head to France and work as an ambulance driver. Two years later, he was working with the Royal Air Force as a trainer, then touring in an RAF exhibition group. Along the way, he documented countless horrors of the war and post-war Europe. Then, in 1946, he joined the Reparation Department, where he had the grisly task of collecting, assessing, and valuing the stolen goods recovered from the Nazis. For months, he helped sort through and document cases and crates of valuables, including everything from jewelry to gold teeth. Some things were sent to auction (with the money going to aid the victims of Nazi persecution), and the items with little to no monetary value? Winton oversaw their disposal in the Atlantic Ocean.

From there, he worked on the implementation of the Marshall Plan and the rebuilding of Europe; along the way he met and married Grete Gjelstrup. After a honeymoon in the U.S., they moved back to Maidenhead, settled down, and went on with the rest of their lives. But that wasn't the end of the story.

He didn't talk about it for a long, long time

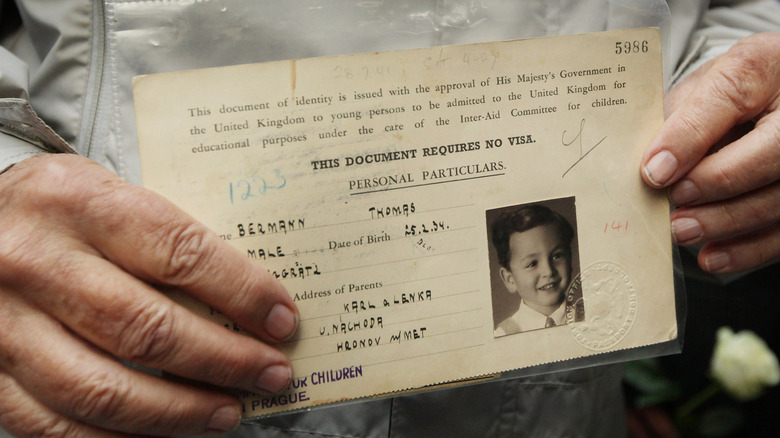

Nicholas Winton married Grete in 1948, and over the course of the following decades, he just sort of didn't mention his death-defying work going toe-to-toe with the Gestapo. It wasn't until Grete found a scrapbook he'd kept — listing the names of the children (including Ruth Halova, pictured, alongside the Prague train station memorial), that she learned about what he had done.

When he couldn't persuade her to just dispose of papers he believed no one would be interested in, she turned them over to Holocaust historians. From there, he came to the attention of the BBC in 1988. He was invited to be an audience member on the show "That's Life," and after the retelling of his story, he was told that the woman seated next to him was one of the children he had saved. Winton was moved to tears, but it was just the beginning: When the program host asked if there was anyone else in the audience who owed their lives to him and dozens rose, it's safe to say that there wasn't a dry eye in the house.

Since then, Winton has been the recipient of scores of honors, including a 2003 knighthood from the British and Czechoslovakia's Order of the White Lion. Meanwhile, Winton was quoted as saying: "Why are you making such a big deal out of it? I just helped a little; I was in the right place at the right time."

Motives and regrets

After the world found out about Winton's actions in Nazi-era Czechoslovakia, he remained almost unbelievably modest. In 2014 — at an impressive 105 years old — he told The New York Times: "I didn't really keep it a secret. I just didn't talk about it." Then, he added, "In a way, perhaps I shouldn't have lived so long to give everybody the opportunity to exaggerate everything I did in the way they are doing today."

Winton's actions very easily could have gotten him sent to the same concentration camps he was trying to help free people from, and while he never really spoke about his motivations, all those decades ago, and the closest he got was perhaps in a 2001 interview with The New York Times. They were talking about the debut of a film that documented not only the grand escape but the lives of the children he saved. He explained: "One saw the problem there, that a lot of these children were in danger, and you had to get them to what was called a safe haven. ... I merely said that when I got back to England, I would find out if it was possible ... to get permission to help these children."

When it comes to regrets, Winton was a little more forthcoming. He had collected the names of 5,000 children desperate for freedom, and had been heartbroken that his appeals to other governments had been refused, leaving him unable to save more.

Efforts to find the missing children

When the BBC did a 2015 story on Nicholas Winton, they shared a surprising statistic: In spite of the 1998 special, there were 370 of the 669 children who had never been found.

There are a few reasons for that, and in addition to the fact that many of the children may have since passed away, there's also the fact that many were too young to remember just how they ended up in Britain. When Hanna Slome spoke with The New York Times in 2015, she said that she had been 14 when she got on the train on May 15, 1939. She never knew how her mother had arranged her escape, though, and it wasn't until 1999 that she saw a Czech-language documentary called "All My Loved Ones." She cried, she recalled, and afterwards, when she looked at the list of Winton's Children, she saw her own name.

The Sir Nicholas Winton Memorial Trust is still looking to make contact with any remaining Winton's Children, or the descendants of their children. Lists — copied by the trust, with the originals now in the possession of the Jerusalem-based Holocaust museum Yad Vashem — detail the names of all the children, their birthdate, the addresses of foster families, and who guaranteed their refugee status. Mistakes — like misspellings — and incomplete data make tracing the children difficult ... but not, they hope, impossible.

Narrowly avoided tragedy

The children saved by Nicholas Winton may have been counted among the fortunate, but even the fortunate have their scars. Once they began stepping forward to tell their stories, it quickly became clear what fate he had rescued them from. According to The New York Times, almost all 669 were orphans by the end of the war. When they said goodbye to their parents — often amid promises that they would be reunited eventually — it was the last time they would ever see their loved ones.

Sarah Kovar spoke to the NYT about her grandmother, Nina Klein. She had been 17 when she boarded one of Winton's transports, with a diamond ring hidden under her tongue. She kept it safe from searches along the way, and wore it for the rest of her life. It was a gift from her mother, and she later told her granddaughter that it "represented survival." Nina's parents died in Auschwitz, along with most of her extended family.

Peter Henry Sprinzels was reunited with his father after leaving Prague for London but never knew what happened to his mother. She had put him on the train and sent him to safety, and it was only when his daughter found her name on a Holocaust memorial wall at a Prague synagogue that he got closure. Ernst Steiner's grandchildren found only a few death certificates: His father and brother died in Majdanek, while the rest of his family simply vanished among millions of the dead.

The 70th anniversary

In 2009, it was the 70th anniversary of Nicholas Winton's kindertransports, and to mark the anniversary, a group of Holocaust survivors — all Winton's Children — once again made the trip from Prague to London. DW says the "children" — all senior citizens at that point — boarded the train at Prague's Main Station, and once again, they headed west. The mood was summed up by Susanne Medas: "I wouldn't have thought it possible, but when I got onto the platform and I saw this train, I started to cry."

Medas had been a teenager, but there had been plenty of little ones, too. Lisa Dasova had been just four years old: "I was so little, I just remember the blue — a blue train. And looking up, I thought the men, the drivers, were dressed in blue. But having looked at it now, it's blue!"

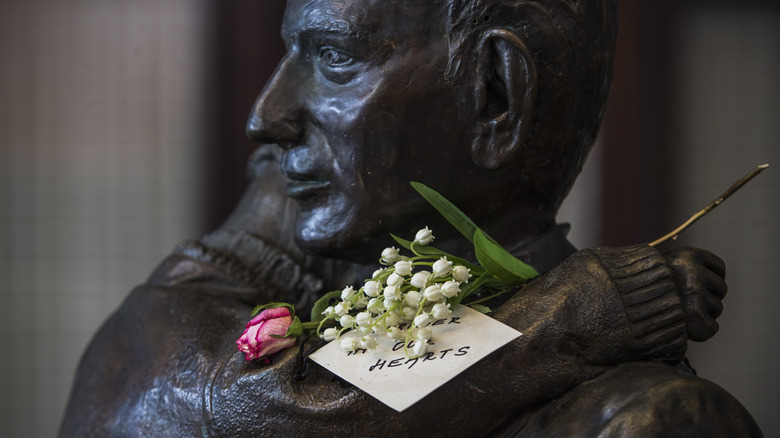

At the start of their journey, many took photos with the statue of Winton that now stands at the train station in Prague. And at the end of their journey? When they disembarked at the Liverpool Street Station, Nicholas Winton was once again waiting to meet them (via NBC). He was, at the time, 100 years old.

Winton's death

In 2016, The Guardian reported on Nicholas Winton's death. He had lived to the ripe old age of 106, and his obituary ended with words from Czech President Milos Zeman. He had written: "You did not think of yourself as a hero, but you were conducted by a desire to help those who could not defend themselves, those who were vulnerable. Your life is an example of humanity, selflessness, personal courage, and modesty."

It's also worth noting that while that same obituary focused on his work during World War II, the Sir Nicholas Winton Memorial Trust notes that even before the story of those 669 children came to light, Winton had already been awarded an MBE for his work with numerous charities — including his foundation of a Maidenhead branch of the charity Mencap (along with a branch of Abbeyfield).

His work with Mencap — a charity dedicated to the support of those with a learning disability — began with his son, Robin, born in 1956. At the time, the recommendation was that children with Downs syndrome be sent to a care facility, and Winton wasn't about to do that. Robin passed away in 1962, but his father continued to work in support of organizations that helped care for those in need. Two elderly care homes were named after Winton's decades of tireless campaigning and fundraising: According to The New York Times, he once raised a whopping £1 million in a single fund-raising campaign. And finally, the Dalai Lama described his life's work (via the Goody Awards): "We should learn from his motivation and from his courage and act, we must carry his spirit from generation to generation."