The Forgotten Mass Imprisonment Of Women By The American Government

Methods used throughout history frequently reveal the real cost of systematic repression and control — in society, where human beings aren't seen as equal, some people are always worth more than others.

When the U.S. government conceived of a grand scheme — one which would save the population from horrors of sexually transmitted diseases — they didn't invent anything new. The Chamberlain-Khan Bill, implemented in 1918, allowed authorities to detain anyone just on the basis of possible infection, and when a person was already in the detention system, it was impossible to get out. But, as it happens in most cases, not all classes were at risk of being detained. The poorer the outcast was, the better their chance to become suspicious. For woman, almost anything could count as questionable behavior, especially at the time, when women started to free themselves from the shackles of puritanical patriarchal norms.

The real victims here were Black, Asian, and Latino communities, women, working class people, and those who didn't fit in with the idea of liberal capitalism. It had nothing to do with STDs, which could be easily treated with the shot of penicillin. The detention centers, laying down foundations for concentration camps – Hitler loved the idea of both concentration camps and coerced sterilization — became a model of how things are dealt with in a modern society, which often prides itself for being a place of freedom and democracy. Here is the forgotten mass imprisonment of women by the American government.

The history of quarantining sex workers

Infectious diseases followed mankind everywhere it went, but the logic of how the illness spreads became known much later. Epidemics of sexually transmitted diseases are well described as far back as in the Old Testament but were seen more as a wrath of god then a logical consequence of certain actions. The middle ages brought the understanding that STDs are somehow related to sexual activity, but due to a very poor understanding of the human body and very limited medical means, people didn't discern between specific illnesses, but saw all symptoms as part of the same disease, as explained in a 2012 article published in the Italian Journal of Dermatology and Venereology.

But, as described in "Sex, Sin, and Science: A History of Syphilis in America," though not even the medical community understood how sexually transmitted infections work, they suspected the source of trouble must be women. Italian doctor Torella confirmed the suspicions by claiming the real reason for disease was a womb — if a healthy woman would have sexual relation to an infected man, her "cold, dry" womb would prevent the spread: "Men are consistently represented as the victim of disease, women as its source," explains historian Mary Spongberg.

Venice, a city state in Italy, developed specific places where women were detained. Zitrelle, as they were called, offered a space where they could lock up not only sex workers, but also other girls as well — mostly the beautiful ones, to protect them from rape, but also from their own sex-loving nature.

It all started with STDs

According to "The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia," syphilis and gonorrhea frequently accompanied American soldiers: Around 15% of them were treated for these two conditions. But in 1912, during World War I, having soldiers who couldn't participate in war posed a national problem, so the government started to come up with the ideas on how to prevent sexually transmitted diseases.

As per "Report of the United States Interdepartmental Social Hygiene Board for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1920," venereal diseases were often connected to crime, shame, misery, and wrecked lives. Around 1,500,000 cases in one year caused huge economic losses, such as $69,000,000 of wage loss and $15,000,000 in extra fees for the military sector. Gonorrhea was the main cause of baby blindness and infertility in men and women, while syphilis caused more occurrences of insanity than any other cause. While the report addresses the, at the time, already known link between STDs and sex work, it also emphasizes "loose morals and promiscuous sex habits," revealed after an analysis of 15,000 cases of "delinquent women and girls." The main problematic factor was that these people with "loose morals" often traveled around, spreading the disease even further. Furthermore, the issue wasn't just sex workers, since some men contracted the disease from non-sex-workers.

The American Plan was created

The General Medical Board of the Council of National Defense provided medical authority to lay down the groundwork for laws concerning sex work, which were soon passed by Congress in 1917, according to "The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia." But the real threat to women was the Chamberlain-Khan Bill implemented in 1918, known also as The American Plan. Two institutions were responsible for its implementation: the Venereal Disease Division of the United States Public Health Service, along with the Interdepartmental Social Hygiene Board.

As explained in "Encyclopedia of Prostitution and Sex Work, Volume 1," the legislation enforced imprisonment, examination, and the quarantine of women who were suspected to carry STDs until they received adequate treatment. All women were potential suspects, especially around military bases, where any women without a male escort or specific letter were subjected to this treatment. Some were detained for around 10 weeks, but others were detained much longer — preteen-age girls were confined until they grew up, at minimum for a year. Many women contracted STDs during these forced examinations.

The plan only targeted women

As explained by scholar Karin L. Zipf in "In Defense of the Nation: Syphilis, North Carolina's 'Girl Problem,' and World War I," when the military forces had a problem with infected men, they turned their attention to the population they could control — young women and girls, frequently working in large cities and cotton mills towns. By firmly reintroducing strict Victorian morals of virtue, every woman who did not live a life according to societal expectations became a problem. This "girl problem" was not an uncommon thing, frequently appearing in places where young women tried to challenge gender or racial hierarchy.

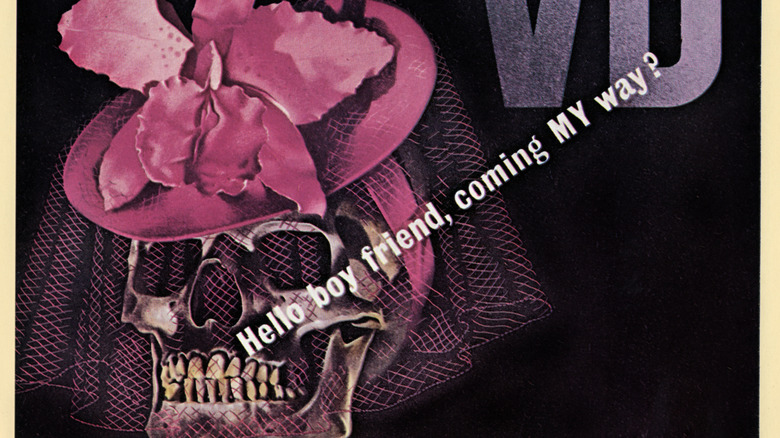

Strong promotional campaigns took place on a national level, promoting self-controlled and responsible manliness, which was endangered by profane reality. However, the legislation did not target men, but women instead: "Those policies regulated women's bodies, leisure, and health solely to facilitate the physical and moral fitness of men." The Commission on Training Camp Activities (CTCA), under the jurisdiction of the War Department, regularly advertised women as sexual objects, whether they were shown as virgins or outcasts. The CTCA first targeted the red districts in towns, forcing them to close, but soon spread its activity to individual women. Any girl suspected of immoral sexual activity was a potential target of newly established Committee on Protective Work for Girls (CPWG).

Women could be detained for any reason

While official guidelines on what made a woman dubious were already quite loose, a big part of the decision was left to the judgment of undercover American Social Hygiene Association (ASHA) agents. They were cruising the streets, looking for potential women without morals, whom they could detain on the basis of "reasonable suspicion." Women were maybe dining alone in a restaurant, or were accompanying a soldier — the reason for their arrest could be simply they were walking down the street, explains Scott Wasserman Stern in "The Trials of Nina McCall: Sex, Surveillance, and the Decades-Long Government Plan to Imprison 'Promiscuous' Women" (via New Republic).

The undercover agents, also known as the "morals squad," often made raids in specific cities, like in Sacramento, California, on February 25, 1919. More than 20 women were detained that day, including Margaret Hennessey, who shared her story with the local media: "At the hospital I was forced to submit to an examination just as if I was one of the most degraded women in the world. I want to say I have never been so humiliated in my life." Hennessey visited the local market with her sister, and despite trying to prove her identity and telling the civil servants her child would be left unattended if they arrest her, they claimed they were approached as "suspicious characters," describes Scott W. Stern for History.

The Plan was in use for more than 60 years

The American Plan had been enforced for many decades, but most forcefully from 1910s until the end of Second World War. After that, the plan slowly started to deteriorate, showing its real repercussions through its cracks. Another experiment, Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male (via CDC), came to light in 1972, leading to additional reviews of the study. The Advisory Panel decided the research was "ethically unjustified" and plain horrible, as the essence of the experiment was to research the effects of syphilis on a male body — by leaving African American men to die from it in pain. This revelation helped turn the public opinion against ASHA and similar social experiments.

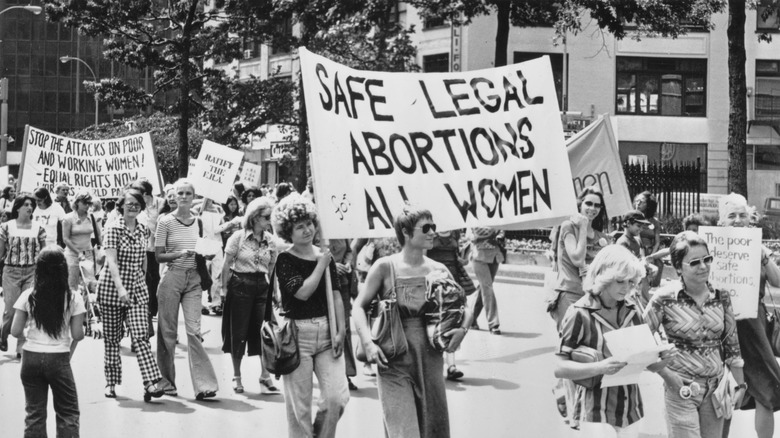

1970s also brought another wave of feminist movements, following government post-war efforts to confine women back to their homes. The feminist approach of questioning the structural foundations of the society revealed numerous mechanisms, such as The American Plan, to repress female population. Women finally had a voice, and they often used it well, explains scholar Jeana Jorgensen (via Foxy Folklorist).

The laws which allow public officials to examine people for STDs, solely on the basis of "reasonable suspicion," are still in place today, although often in a different form, now part of general public-health legislations. This doesn't only apply to STDs, but other illnesses as well, clarifies History.

The plan had strong support from people in power

The Plan was not a secret amongst the elite, and many people in high positions strongly endorsed the project. The attorney general sent letters to all attorneys in the U.S., notifying them about the law, while district judges got another version, warning them to not hinder its implementation. Governors and state councils gladly embraced the new federal law and enforced it in their communities. Even the American Civil Liberties Union openly promoted the Plan, with founder Roger Baldwin proposing to the organization's local departments that they could help out the moral squad. New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia and politician Earl Warren both personally encouraged the plan's implementation, reveals History.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., funded the project for several decades, while Eleanor Roosevelt and California governor Pat Brown openly supported the concept. They did it in a nice way, of course, omitting the part about forceful incarcerations, focusing on positive sides of sex education and STD prevention instead (via New Republic).

The authorities practiced coerced sterilization

Detained women were treated with different horrendous procedures, despite the existence of penicillin as an available cure (via CDC). Common cures were injections of mercury, along with regular beatings and abuse. Some women were even sterilized, explains Scott W. Stern for Time. This was problematic, not only for the obvious reasons, but due to more widespread sterilization plans in the country.

As reported by Jeremy Rosenberg for KCET, coerced sterilization wasn't a foreign concept to the U.S. government, which had already implemented the "Asexualization Act" in 1909, with additional improvements legislated in 1913 and 1917. These laws enabled Californian authorities to forcefully sterilize over 20,000 people between 1909 and 1979, on the basis that these people were either too mentally ill, poor, drunk, or promiscuous to reproduce. An "Asexualization Act" was implemented in other states as well, and one even made its way to Germany, where the Nazi government sterilized over 2 million victims.

The ideas of eugenics weren't new, and they were used against different populations in different areas. California targeted Latino and Asian populations, while other Southern states tried to affect African American communities — like Mississippi through its "Mississippi appendectomies," program for medical students to practice hysterectomies on women of color. North Carolina focused on young girls. Coerced sterilizations on Native American women took place as late as in the 1980s, but the majority happened in the 1970s — to half of the Native American female population, summarizes Lisa Ko for PBS.

Women did fight back

Many women opposed The American Plan and fought back, stating that the plan was sexist and discriminatory. Activists Edith Houghton Hooker and Katharine Bushnell organized several campaigns which promoted the complete abolition of the program, explains Scott W. Stern (via New Republic).

But women who were subjected to the plan frequently protested as well, sometimes by rioting and burning down detention facilities. Others went to court; one of them was Nina McCall, a 19-year-old woman. She was arrested, examined, fed arsenic, and detained for three months in Michigan in 1918. In 1921, she filed a court case, took it all the way to Michigan Supreme Court — and won. But only because she was detained without "reasonable suspicion." Her case, Rock v. Carney, became a template for later court rulings, but only to endorse further detentions on the basis of quarantining.

With the wave of feminism in the 1970s, women became even louder — while the laws were still in place. Well-known feminist Andrea Dworkin was arrested during a Vietnam War protest in New York in 1965 when she was only 18 years old. The STD examination that followed the arrest was so forceful, she bled for days after, and when her family doctor saw her wounds, the doctor cried. Dworkin decided to fight back, informing the newspapers which published her story. This led to a government investigation and finally the termination of the Women's House of Detention in Greenwich Village, reports Ariel Levy for New York Magazine.

The Plan laid down foundations for many other repressive systems

The idea of public hygiene, which could be controlled through restrictions of specific people, laid down foundations for several repressive systems still in place in society. The HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s was handled in the same way, by forcefully quarantining gay individuals and sex workers. The authorities referenced The American Plan throughout the process, citing its wide success — but also its legal frame for a massive breach of human rights, explains Scott W. Stern (via Foxy Folklorist).

During World War II, Nazi Germany wasn't the only country that found the idea of concentration camps and forced sterilizations appealing: These ideas were also used to build internment camps during the Second World War. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a response to the Great Depression, used camps from the American Plan that were soon turned into detention centers for people of Japanese or German heritage (via New Republic).

Statistics show that the number of women imprisoned in the U.S. is consistently growing, more than any other population in the country. A majority of women detained in female prisons, a staggering 70%, have been working in sex industry, reports Kim Kelly.

The real reasons for The Plan were misogyny, racism, and elitism

Despite numerous quasi-progressive ideas of health, virtue, and cleanliness, the ideas behind The American Plan were just the extension of forces firmly present in Western society. As emphasized by Scott W. Stern (via Foxy Folklorist), these methods allowed doctors to gain authority over individuals who were deemed less worthy, whether for their social status, skin color, or gender — the most affected group by far were women of color. It also allowed medical professionals to extend their power over the bodily autonomy of individuals, by stating "the unimportance of consent when it clashed with their ideas of what was best."

As noted in "In Defense of the Nation: Syphilis, North Carolina's 'Girl Problem,' and World War I," the Chamberlain-Kahn Act was written in gender neutral terms and was never specifically targeted at women. The reality showed a stark contrast, as the newly established reformatories and concentration camps were filled up only by female imprisoners. The plan evolved in the times when middle-class women started to gain more freedom, leaving stiff and virtuous Victorian beliefs behind. The flappers — fun-loving, free, and confident women — were soon socializing with the "charity girls," similar girls from a working-class background. The latter were often the perfect target for the moral squad, as they were also fun-loving, free, and confident — but poor. This, in the eyes of the government, was already enough to be seen as a danger to society.