The Most Common Ways To Die In 1800s America

Modern humans take a lot of things for granted. Air conditioning. Starbucks. 24-hour grocery stores. Indoor plumbing. If you can afford health insurance, you probably also take medical care for granted. Thanks to huge advances in medical science, personal hygiene, and general human welfare, people don't die from all the bonkers things they used to die from 200 years ago. When was the last time you lost a friend or family member to intestinal parasites? Hopefully never. But according to the 1860 census report, "Mortality of the United States," worms killed almost 2,000 people in that year alone. Other causes of death that since then have almost completely dropped off the American radar: smallpox (1,271 deaths) and measles (3,899). Just for comparison, the last smallpox victim died in 1978, and only 12 Americans have died from measles since 2000.

Similarly, today Americans die in droves from things that weren't really that common in the mid-1800s. In 1860 only 3,292 people died from cancer (though another 606 died from tumors, and it's hard to really say what the distinction was). That's compared to 608,570 people who died from cancer in 2021 (via American Cancer Society). And only 528 people were murdered in 1860, compared to 24,576 in 2021 (via the CDC). So just in case you were starting to think you have it easy here in modern America, well, you don't.

Diarrhea

So let's just start with one of the grossest items on the list — diarrhea — which today most people tend to think of as more of a symptom than a disease. Back in the 1800s, it was a general umbrella term used to describe loose, watery stools that were not attributed to a specific infection like dysentery. It was a big killer, too. According to the census report, "Mortality of the United States," diarrhea claimed the lives of 7,850 people in 1860.

In today's America, you don't often hear about people dying of "diarrhea," primarily because most people understand that the real killer is the dehydration that can happen after a long bout with this symptom. Today, if you can't manage to replace fluids with Gatorade or Pedialyte at home, you can always get IV fluids at the ER. Deaths do still happen sometimes, though. In fact, a study published by JAMA found there are roughly 8,000 diarrhea-related deaths in America every year, which does seem pretty high compared to those 1860 numbers. Remember, though, that figure includes all diarrheal illnesses, and there are about 10 times as many people in the United States today as there were back in the 1800s, so proportionately the numbers are really not that alarming.

Worldwide, though, diarrhea is still a big killer. Today diarrheal illnesses (which include cholera and dysentery) kill about half a million children every year, according to the World Health Organization.

Whooping cough

Vaccines have made it possible for more people to survive childhood and those of us who do tend to grow up completely unaware of just how bad vaccine-preventable illnesses actually are. One excellent example is pertussis, colloquially known as whooping cough. This bacterial illness is a little bit like our dear friend COVID-19 in that it spreads from person to person via respiratory droplets (via the CDC), and it causes severe cough.

Once you have pertussis, symptoms progress slowly over a couple of weeks (via the CDC). At first you feel like you have a cold and you're all, "I can totally do this pertussis thing!" Within a couple of weeks, though, you'll progress to having coughing fits so violent that you can't breathe through them, and you'll probably barf when they're over. Not fun. And to make it even more not fun, the CDC says symptoms can persist for up to 10 weeks, which is why some people call pertussis the "100-day cough."

In the 1800s, pertussis was a big killer. The 1860 census counted 8,408 whooping cough victims. The disease was especially fatal for children under the age of 1, accounting for 5% of total infant deaths that year. Today pertussis is less of a problem in America because of widespread vaccination and the fact that it can be treated with antibiotics. Still, 50% of babies who get pertussis will need hospitalization, so it's not a trivial disease.

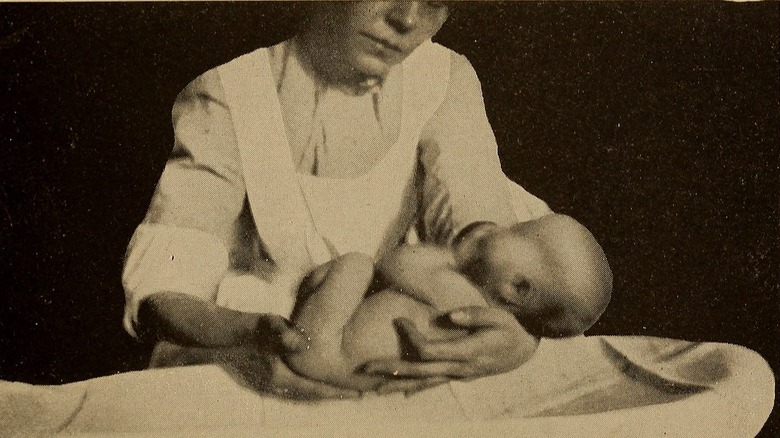

Convulsions

According to the "Mortality of the United States" census document, convulsions killed 9,077 Americans in 1860. In those days "convulsions" (like diarrhea) was sort of an umbrella term used to describe any disorder that caused spasms, usually in children. According to an 1866 clipping from Medical Record, this could include everything from neonatal seizures to epilepsy to tetanus, the latter of which causes spasms of the jaw muscles, as per the CDC. For children under the age of 1, convulsions were considered so universally fatal that doctors sometimes didn't even bother to attend patients who had this symptom, because there wasn't anything that could be done for them.

Convulsions were especially dangerous for newborns, and today it's clear why. According to the UCSF Benioff Children's Hospitals, babies deprived of oxygen during birth (either because the placenta detached from the uterus too soon or because the umbilical cord was compressed during labor) could suffer brain damage from lack of oxygen, which can lead to seizures after birth. Babies can also get infections like bacterial meningitis and toxoplasmosis in utero, have birth defects or blood clots in the brain, and can even suffer strokes. Premature and low-birth-weight babies are also more likely to have seizures in the first days of life.

The difference between now and the 1800s is MRIs, CT scans, anticonvulsant medications, and medical knowledge. Newborns still die from things like oxygen deprivation and meningitis, but the cause is less of a mystery, and many of the conditions are treatable.

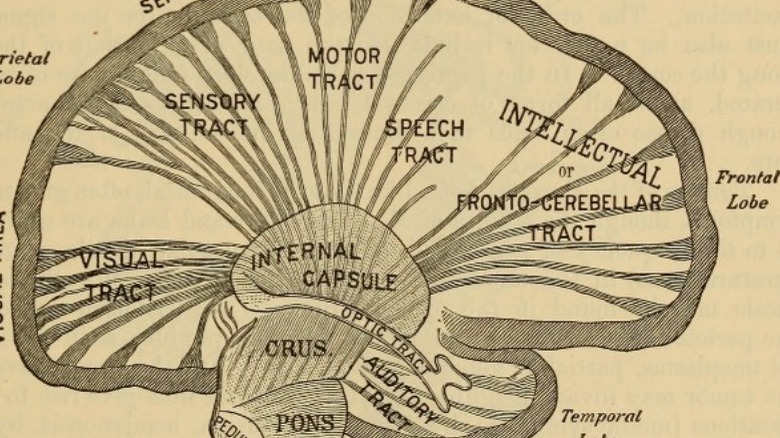

Cephalitis

"Cephalitis" is encephalitis without the first two letters. It is not a specific disease, but rather a symptom of something else. According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, people with encephalitis have inflammation in the brain, which can lead to a host of other symptoms including light sensitivity, stiff neck, headache, and confusion. It's still a big problem today, affecting roughly 250,000 Americans in the last decade. Sometimes the cause is a virus like measles or chickenpox, sometimes it's an autoimmune disease, but in up to 40% of cases, the cause is a mystery.

It was even worse in the 1860s, which was still a couple of decades before doctors really started to have a good understanding of "germs," what exactly they were and how they could make people sick. That explains why the 1860 census gave cephalitis its very own, very vague category, also noting the common term "brain fever" that was often used to describe the condition. Brain fever was a scary name for a mysterious illness, which according to JSTOR Daily sometimes found its way into classic novels like "Madame Bovary." Some doctors even thought "brain fever" was a mental health problem. Sufferers might have experienced some kind of emotional trauma, or maybe they were just overthinking things. Like, literally overthinking things to the point where they short-circuited their brains.

In 1860, 10,399 Americans died from cephalitis. Even today, the mortality rate in hospitalized encephalitis patients is nearly 6% (via PLoS One).

Dysentery

You can't say anything about dysentery without mentioning the Oregon Trail, so let's just get that out of the way first. "You have died of dysentery." Yes, ever since the Oregon Trail made its debut in 1971, people have been dying of dysentery from coast to coast, sometimes a few times in a row every couple of minutes or so. But dysentery is also an actual thing that people died of in real life (and still do).

Dysentery is distinguished from diarrhea by its severity and cause. People with dysentery have bloody diarrhea, while regular diarrhea is blissfully blood-free. Dysentery is also caused by two specific microorganisms. According to the NHS, the first is a bacteria called Shigella, which people usually encounter while eating food that's been in contact with the stool of someone else who has this form of dysentery (via Cleveland Clinic), so that's gross. Wash your hands, people.

The second form is amebic, which means it's caused by a single-celled organism, specifically a protozoan called E. histolytica, which also spreads via poop. According to the 1860 census report "Mortality of the United States," 10,468 people died of dysentery that year, so clearly the "wash your hands after using the toilet" ad campaign had yet to sweep the nation. Today, about half a million Americans get dysentery every year, which means the message still isn't percolating the way it should be — though to be fair, most Americans who get dysentery today don't die from it.

Old age

After reading all this, you're probably thinking people in the 1800s never died from old age. No vaccines, poor public health measures, lousy sanitation — it seems pretty obvious that some disease or another is going to take you down before you get old enough to buy a rocking chair and tell kids to stay off your lawn. But as it turns out, a lot of people in the 1800s did live long enough to become old geezers.

The 1860 census names "old age" as the cause of death for 10,887 people. It does that with some caveats, however. "Old age should include only those who die from exhaustion of vital force from protracted use of life, without any disease or organic lesion," the author writes. The author then goes on to note that most of the "old age" deaths in the report probably didn't meet that definition, since old people are more likely to die from illnesses that younger people usually survive. In other words, a lot of the 10,000 plus "old age" victims probably died of something like influenza or bronchitis. It was listed as "old age," though, simply because a younger person would have been more likely to survive the same illness. In fact, the author also notes that some of the people who were reported as dying of old age were less than 50 years old, so just in case you needed confirmation that life in the Wild West was rough, well, there you go.

Remittent fever

Modern medicine describes remittent fever as a fever that fluctuates by more than a couple degrees but is never normal (via Journal of Infection and Public Health). Today, doctors know this type of fever is usually caused by some kind of infectious disease, but in the 1800s it was just called a "fever" because the concept of disease-causing agents was still on pretty shaky footing. The cause of the fever wasn't always known, so the fever itself was named as the illness.

There's also some likely confusion between what "Mortality of the United States" calls "remittent fever," which killed 11,120 people in 1860, and the less-common cause of death labeled "intermittent fever." According to the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, doctors of the time often used both words when talking about known illnesses like malaria. The census document doesn't go into much detail about this cause of death except to say it claimed about twice as many lives in the summer as in the winter, which also points to malaria since it's mostly a summer disease (via Malaria Journal). Malaria isn't something you worry about while you're swatting mosquitoes at a summer barbecue anymore, but it was a big problem in the United States up until the CDC launched its mostly successful 1946 campaign to eliminate the disease. Mostly, because there are still around 2,000 cases a year right here in America (via Current Tropical Medicine Report).

Dropsy

You also don't really hear about people dying of dropsy anymore, though that's not because dropsy is no longer a thing, it's because it has a different name. Today, dropsy is called edema or more simply, "fluid retention." Medically speaking, it's the swelling of tissues due to a build-up of fluids.

Fluid retention is most obvious in the ankles and feet, but it can also appear in the stomach — and it can manifest as weight gain or, more worryingly, trouble breathing (via Health Direct). Just having swollen feet and ankles seems pretty benign at face value, but when edema shows up it's often a sign of something a lot more dangerous like heart failure, kidney failure, or lung disease. That explains why "dropsy" was such a big killer in the 1860s — these are dangerous conditions that are hard to treat even today; back then they were lethal. The 1860 "Mortality of the United States" document counts 12,090 people as victims of fatal dropsy. To be fair, though, even in 1860 doctors were aware that dropsy was a symptom rather than a disease. The author of the 1860 report called it "an unsatisfactory designation of disease or cause of death," and noted that it was usually caused by disease of the heart.

Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever is another illness you don't hear much about anymore, but it is still very much a thing. You do hear about its close cousin Salmonella, which is what keeps you within three feet of a bathroom after you foolishly ate grocery store sushi. Salmonella is usually not serious for healthy people, but when small children, the elderly, and immunocompromised people (via the CDC) come down with it, it can be life-threatening.

Typhoid fever is caused by two types of Salmonella, specifically serotype Typhi and serotype Paratyphi, notes the CDC. Today, Americans who come down with typhoid fever usually pick it up while traveling to other countries. That's because health authorities in the U.S. have solved most of the problems that contribute to the disease, which is spread when sewage comes into contact with the food and water supply. According to the CDC, it can also spread person-to-person, generally when someone who has the illness gives you a coke or something after using the toilet and not washing up afterward. In other words, if you get typhoid fever it's literally because you ate poop.

By the 1860s, people were aware that you could get typhoid fever this way (in 1838 a lawyer even came up with the radical suggestion to isolate human excrement in order to stop the disease from spreading). But great sanitation systems weren't really widespread by the time of the 1860 census, and that year 19,236 people died as a result of eating someone else's poop.

Croup

For new parents, croup is a dreaded condition — not because it's typically fatal but because it usually requires staying up all night long with a very unhappy infant in an uncomfortably steamy bathroom. According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, it's usually caused by something like influenza, RSV (a respiratory virus that causes cold-like symptoms but can be dangerous for babies), or other cold viruses. It's distinguished from other kinds of cough because the voicebox and windpipe become swollen, which can make it hard to breathe and cause the distinctive whistling sound that gives croup its name (meaning to cry hoarsely or croak). Because babies have smaller airways, the swelling can become an emergency.

Today, croup is fairly easily treated with medication as long as parents seek medical care in time. In the 1860s, though, the only way to clear a swollen airway was to perform a tracheotomy. According to "Tracheotomy: Airway Management, Communication, and Swallowing," the procedure was really just a last-ditch effort that didn't usually work. When it did, the person would have to live with a tracheotomy tube for the long term. For many patients, though, this radical surgery wasn't even an option — parents just had to watch their child slowly suffocate.

Croup wasn't just a terrible killer in those days, it was also heartbreakingly common. According to "Mortality of the United States," it killed 15,211 people in 1860, nearly 90% of them children under the age of 5.

Accidents

If you've ever seen "A Million Ways to Die in the West," you know that people in 1800s America commonly died from gunshots, stabbings, wolf predation, exploding cameras, rampaging bulls, being crushed to death by large blocks of ice, and methane poisoning from their own flatulence. Yes, it was a dangerous time, and not only were liability laws and safety regulations a bit lax, but medical science didn't really know how to save people from major trauma or excessive farting.

Hence, the 1860 "Mortality of the United States" document lumps 18,090 deaths into the "accident" category, which sadly does not include flatulence or exploding cameras but does include burns and scalds (4,266 people), drowning (3,121 people), lightning (191 people), firearm accidents (741 people), falls (1,323 people), railroad accidents (599 people), strangulation (291 people), suffocation (2,129 people), and poison (950 people). That last category also includes snakebites and might include a case or two of flatulence-related methane poisoning, but probably not.

There were also 4,178 "accidents not specified" and a few other accident-related causes of death not listed here simply because the list was starting to feel a bit bloated, and some of them (like neglect) frankly don't seem very accidental. Still, it's obvious that it was pretty easy to die in stupid ways back then since this particular kind of mortality is pretty high on the list of the most common ways people died in 1800s America.

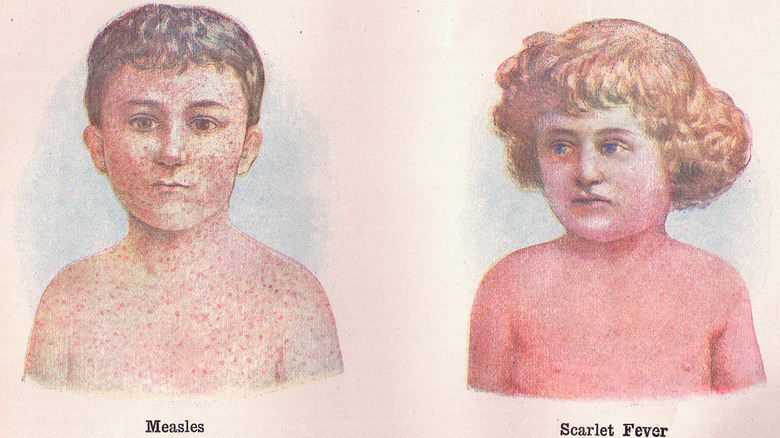

Scarlet fever

If you read "The Velveteen Rabbit" as a child, you were forever traumatized by the idea of scarlet fever. Not because you thought you were going to die from scarlet fever, but because kids with scarlet fever had to burn all their stuff, and that's really just about the worst thing that can happen to a kid. Today, kids can (and do) get scarlet fever, but the difference is that doctors can now prescribe antibiotics, so it's not a serious illness like it once was.

Scarlet fever is caused by Group A Streptococcus, the same bacteria that causes strep throat. According to Everyday Health, the disease often begins in the throat and, in some people, develops into scarlet fever, which causes a bright red rash and a bumpy, red tongue. Like croup, it's mostly a childhood illness, though anyone can technically come down with it if they're unlucky enough.

Today, the CDC describes scarlet fever as "a mild infection." The 1860 census document, though, described it as "the dread scourge of children," noting that the 26,402 people who died from it accounted for a full 7.41% of all deaths recorded that year. According to StatPearls, scarlet fever mortality in the pre-antibiotic era was roughly 1 in 3; today it's less than 1%. In case you haven't ever thought to be grateful to antibiotics, by the way, they're probably the reason why you're alive to read this.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is still a big killer, even today. According to the American Thoracic Society, it's responsible for 16% of all deaths worldwide in kids under the age of 5. Better access to healthcare makes it less deadly in America, but it's still the leading cause of hospitalizations among children.

Pneumonia is a disease of many causes. Bacterial pneumonia is often caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, as per the American Lung Association, but there are a few other bacteria that can cause it, too. Viral pneumonia can occur after infection with a host of different viruses, including influenza, RSV, and our good friend COVID-19.

Today, bacterial pneumonia can be treated with antibiotics (though its severity often depends on whether or not the particular type of bacteria is resistant to antibiotics), but there are no good treatments for viral pneumonia, so how sick you get often depends on which side of that coin came up. In the 1800s doctors didn't even have antibiotics (penicillin wasn't discovered until 1928), so when you got pneumonia about all they could do was throw their hand up helplessly and tell your family to start praying. According to "Mortality of the United States," pneumonia in 1860 was "among the most destructive diseases," claiming the lives of 27,094 people.

Consumption

If you watch period films, you know what consumption is. A beloved character is stricken by this dreadful disease and is sent off to live in a "sanatorium," where he or she slowly wastes away and dies. That fiction was an exact mirror of the truth, though the sanatorium wasn't even a thing in the 1860s (the first one appeared in the United States in 1884). The belief was that fresh air and healthy food could help you recover, though the facilities also acted as isolation centers that prevented further spread of the disease. Sanatoriums probably did help some (wealthy) people recover, but consumption didn't really stop being a big killer until the antibiotic streptomycin came along in 1944.

Today, there's a different word for consumption, but it's the same illness. Modern tuberculosis doesn't usually kill Americans, though. If you're unfortunate enough to develop it, you take antibiotics and you recover. In other parts of the world, people aren't so lucky. According to the American Lung Association, tuberculosis claimed 1.5 million lives in 2013.

The 1860 census numbers tuberculosis deaths in the United States at 49,082, calling it "the great destroyer here and elsewhere." It was the cause of nearly 14% of all American deaths that year. Worldwide, things weren't much different. According to PBS, by the early 20th-century tuberculosis had claimed the lives of one out of seven people who had ever lived on planet Earth.