Disturbing Details Found In Napoleon's Autopsy Report

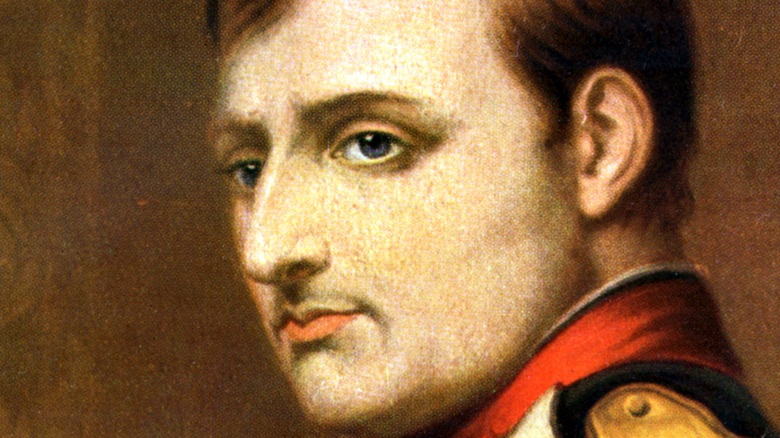

Napoleon Bonaparte, first emperor of France and monumental personality of European history, died in disgrace. On October 15, 1815, less than six months after his defeat at Waterloo, the British Navy ferried Napoleon and a small entourage to St. Helena, a bleak, rocky island in the cold South Atlantic. Neither his wife, Marie-Louise of Austria, nor his son, Napoleon II, came with him (via Britannica). It was a sad fate for the man whom the philosopher Hegel called "the soul of the world ... an individual, who ... seated on a horse, stretches over the world and dominates it" (per the Foundation Napoleon).

Born on the Mediterranean island of Corsica, Napoleon felt like a foreigner in France, where he moved as a boy (per Britannica). As a young officer he would embrace his new French identity and fight his way to the top of French society by sheer willpower. In 1804 he crowned himself Emperor of France, thrusting himself into the company of Charlemagne, Julius Caesar, and the European pantheon. Defeated by Britain and her allies in 1814, he made one last daring grab at power, escaping captivity on the island of Elba to reclaim his empire. But it was short-lived; and at the age of 46, the great man was living in a "wretched hovel" on St. Helena, guarded closely by his English captors.

The eagle caged

Napoleon spent his eight-year exile playing cards, dictating his memoirs (as shown above), and gaining weight. He occasionally showed signs of good humor — a letter from one Mrs. Catherine Younghusband on St. Helena depicts him as friendly, even mildly flirtatious, although clearly bored with his new life (per the Fondation Napoleon). But overall, he was not well. As Dartmouth Medicine recounts, Napoleon suffered from fatigue, chills, jaundice, and abdominal pain on and off. He dismissed two British doctors in 1819, as the Fondation Napoleon explains; his uncle, the Cardinal Fesch, sent him a new doctor, fellow Corsican Francesco Antommarchi.

This was a blunder. Antommarchi was a young man of 30 with very little experience. He claimed to be a specialist in anatomy, but his resume consisted largely of plagiarism and exaggeration. His main qualification was flattery, which the Emperor saw through immediately — he called Antommarchi "a blockhead, an ignoramus, a fop, a sneak."

Napoleon felt weaker and weaker through the early months of 1821, made worse by Antommarchi's insistence on huge doses of laxative. By April Napoleon was vomiting blood. On May 5, 1821, he finally succumbed, aged 51.

'Resembling the sediment of coffee'

What exactly had killed Napoleon? No one really knew. One British doctor, called in to assist the incompetent Antommarchi, even suggested that the Emperor's illness was "more mental than physical and not serious" (via Fondation Napoleon).

Both Antommarchi and the British doctors on St. Helena insisted on their right to perform an autopsy, but bizarrely, their reports didn't match up at all. Antommarchi had the first go. He declared that Napoleon's lungs were wrecked. The ganglions of the lungs seemed enlarged and distended. "The right lung," he wrote, "was slightly compressed by effusion," with the membranes of the thorax swollen with orange fluid. Pulmonary effusion in particular is a classic tuberculosis symptom, as the Journal of Thoracic Health (posted at the National Library of Medicine) makes clear, but for unknown reasons — possibly sheer ignorance — Antommarchi never named the disease. He also found the liver to be obviously diseased and swollen with blood, and the pericardium (the membrane surrounding the heart) covered in small tumors. If this was an accurate observation, it's hard to know quite what it all means.

Two autopsies

The British doctors took a stab once the young man had finished. Their report could not be more different. For one thing, they found the lungs in excellent shape. The doctors bickered over the condition of the liver, some of them insisting that it was healthy and others agreeing with Antonmmarchi that it was swollen and diseased. Eventually they measured the whole organ with a tape; but that strange measure revealed nothing. What they could agree on, however, was that an ulcer in Napoleon's stomach had not only made a complete perforation — a hole in the bag, as it were — but had turned cancerous. "The stomach was filled with a considerable quantity of substances of a color resembling the sediment of coffee which exhaled an infectious odor," they wrote (quoted by the Fondation Napoleon website).

Antommarchi, who seems not to have noticed anything particularly the matter with the Emperor's stomach, refused to sign their report. Theories abound about this bizarre, contradictory list of symptoms; some have even suggested poisoning. But the most likely cause of Napoleon's death was stomach cancer, the same disease that killed his father (per Bonesprit), made worse by stress and incompetence.