What Pre-Colonized Mexico Was Really Like For The Aztecs

Mexico has a colorful history, blossoming with cultures rich in art, song, and philosophy, and the Aztecs are among the most famous. According to Britannica, the Aztecs ruled the region in the 15th and 16th centuries. They were an urban society, living in several city states around Lake Texcoco, the largest of which were the cities of Tlacopán, Texcoco, and Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital. Together, they controlled an empire known as Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān or the Triple Alliance, as per Time.

Humans had lived in Mesoamerica for at least 21,000 years. Early cultures, like the Olmecs, went on to influence later cultures like the Maya and Aztecs. Then, everything changed when the Spanish attacked. In their quest for gold and riches, the conquistadors ransacked everything in their path. The Yucatan Times explains that this included burning nearly every book they could find, on the orders of Bishop Diego de Landa in 1562. As a result, most surviving accounts of Aztec life were made by the same people who were ultimately responsible for the destruction of their society.

The people themselves didn't refer to themselves as Aztecs, but as Mexica, and their name lives on in the name of Mexico itself. They were likely named for Metzliapán, meaning "Moon Lake," an old name for Lake Texcoco. While most people know little about them beyond brutal depictions of war and human sacrifice, the Aztecs had a complex and fascinating culture.

The Great Cities of the Aztecs

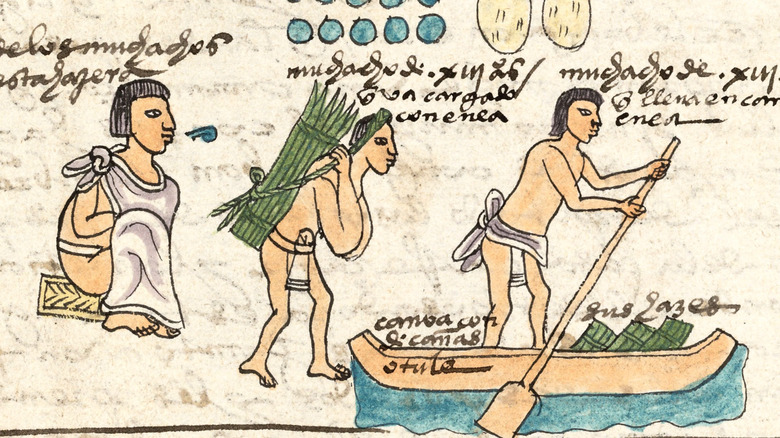

Mesoamerica has a long tradition of building cities, including Teotihuacán, one of the largest cities in the world when it was built. The Aztec contribution to this legacy was their capital of Tenochtitlán. According to Live Science, the city had an extensive system of roads and canals used by hundreds of thousands of people — estimates say at least 400,000 people lived in Tenochtitlán (via Britannica), making it the largest city in pre-colonial Mesoamerican history. As centers for trade and culture, most Aztecs would have either lived in or near cities.

So grand was Tenochtitlán that the leader of the conquistadors, Hernán Cortés, wrote about it extensively in a letter to the king of Spain, comparing its size to the Spanish cities of Seville and Cordova. His descriptions of the narrower avenues being "half land and half water ... navigated by canoes" sound reminiscent of the Italian city of Venice. In his letter, Cortés seems especially impressed by the size of the roads and bridges. Other conquistadors also made written accounts (via El Universal), describing how they were astonished to see cities and villages seemingly built on the water. One, in particular, noted how they "said that it was like the enchantments" and that "some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream." Despite the disbelief of the Spanish, Tenochtitlán wasn't some magical wonderland, but simply a place where people lived out their daily lives.

Aztec Social Hierarchy

Aztec society had a strict class structure. Live Science explains how people living in Tenochtitlán lived in clan groups known as calpulli, each of which would contain several macehaultin (commoner) families, led by nobles known as pipiltin. People's social status was reflected by the homes they lived in, with only nobles being allowed to build houses with a second story.

According to The Tarlton Law Library, Aztec pipiltin were members of high society, like government officials, military leaders, and high-ranking priests. The most prestigious pipiltin were tecuhtli (lords). The macehaultin class were a combination of farmers, lower ranking priests, artisans, and merchants, who paid tributes to their pipiltin by giving goods and services. The oldest macehaultin could have the chance to join a council of elders who worked with the pipltin to run the community. The lowliest class of people, who owned no land, were serfs and slaves. Serfs lived outside the calpulli and worked farmland they didn't own. No one was born into slavery, but people could become slaves either as punishment or by selling themselves voluntarily to pay debts. However, slaves were still free to marry, buy their freedom, or even find someone to substitute their place.

Interestingly, while Aztec society had rigid gender roles, women had a fair amount of freedom. A study in the journal Ethnohistory explains how men and women had parallel social spheres. In areas from politics to religion, Aztec women were able to hold positions of notable authority.

Clothes Maketh the Aztec

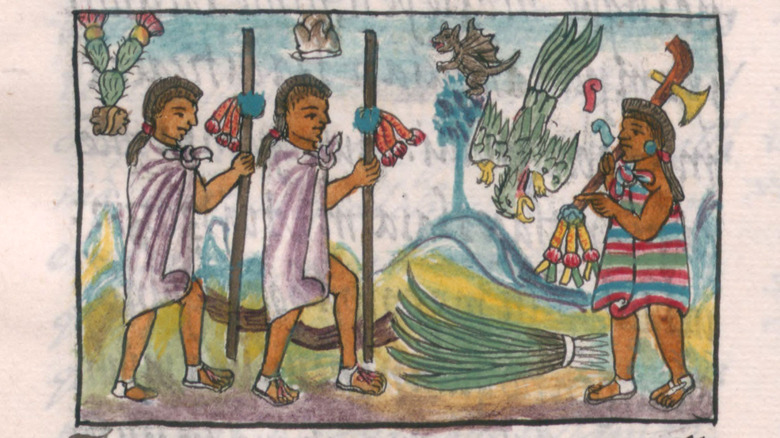

Anthropologist Patricia Rieff Anawalt explains in her book, "Indian Clothing Before Cortes," how clothes signified people's place in Aztec society, giving an immediate visual indicator of their social status and even cultural affiliation. The Aztecs were multicultural, incorporating other ethnic groups like Maya, Mixtec, and Tarascan, with their own styles of clothing. A study in the journal Archaeology elaborates that they used sumptuary laws (laws to prevent excessive extravagance), limiting the ornamentation and even the type of fiber that could be worn by commoners.

History Crunch explains how Aztec men would typically wear a kind of loincloth called a maxtlatl and a cloak-like outer garment called a tilmahtli, with nobles wearing much more ornate tilmahtli. Women would wear a shirt called a huīpīlli and a cuēitl, which was a kind of long skirt. Sandals, named cactli, were a sign of social status, only permitted to be worn by nobility — though even the nobles had to remove their footwear to enter temples or to be in the presence of royalty.

History Crunch also notes the Aztecs loved jewelry, which was worn by both men and women. Upper classes were always seen wearing more necklaces and bracelets, particularly those made from eye-catching gold and gemstones. But even commoners wore jewelry, often made with shells and feathers. Some feathers were particularly valued, like those of the quetzal bird, known for its striking teal plumage. Quetzal feathers were exclusively worn by royalty, used in vibrant headdresses.

Life as an Aztec Farmer

If you were a member of Aztec society, there's a good chance you would have been a farmer. As History Crunch details, farmers led a simple life, living in more humble homes, owning less elaborate clothes and artwork. Farmers, like all Aztecs, received compulsory education, according to Live Science, learning to use a variety of copper tools that they had at their disposal. With well developed agriculture, World History Encyclopedia explains that there were two distinct groups of Aztec farmworkers. Laborers would tend the fields and perform duties like planting and irrigation, while horticulturalists would apply their knowledge about transplanting, crop rotation, and the best time to harvest.

Most Aztec farming was plant-based, with farmers only keeping a few animals like turkeys and ducks. Instead of animals, they bred a huge variety of plant crops using terraces and artificial floating islands known as Chinampas. These were built on freshwater lakes using layers of mud and clay, with constant irrigation giving an exceptionally productive way to produce vegetables. They're still used in some parts of Central America today.

Aztec crops were mostly recognizable as things now eaten worldwide. Corn was their main dietary staple, but farmers also produced things like beans, peanuts, tomatoes, chile peppers, potatoes, pineapples, strawberries, and sunflowers. Additionally, they grew non-food crops like rubber trees and cotton, as well as some ornamental flowers like fuchsias. A paper in the journal HortScience argues that these domesticated plants should be considered a contribution of Indigenous Mesoamerican cultures to all of humanity.

Aztec Cuisine

With their skill in agriculture, the Aztecs had an exceptionally varied diet, full of fresh fruit and succulent vegetables, which they enjoyed making into sauces, as per World History Encyclopedia. The main part of their diet, though, was corn — so important in Aztec culture that it even played a central role in their religion and mythology. As History Hit explains, the most common Aztec foods were tortillas and tamales, still enjoyed across Central America today; they made these with a process familiar in modern Mexico, called nixtamalization, to break down the corn using alkaline limewater before making it into flour. Between meals, a popular Aztec snack was popcorn.

Aztecs typically ate twice daily. After a few hours of work in the morning, many people would enjoy a bowl of cornmeal porridge, spiced with chile or sweetened with honey. Another popular early meal was tortillas, beans, and a rich sauce. Their second meal would usually be in the afternoon, around the hottest time of the day. This late lunch would usually involve tamales or tortillas, often with beans and a casserole made with squash and tomatoes. Aztecs weren't exclusively vegetarian though. According to World History Encyclopedia, they also ate a variety of meat, from ducks and wild pigs to frogs and salamanders. Even certain insects were a common part of the Aztec diet.

There were several drinks to enjoy with their food too. Commoners often drank an alcoholic beverage called pulque, while nobles were more likely to enjoy cacao-based drinks.

Marketplaces were a hub of activity

Trade was a central part of Aztec society, and every city district had its own marketplace. History On The Net describes how all kinds of goods could be found there, from things like food and cloth, to obsidian knives and tools, to pottery. But as well as trading, the marketplace was also a social space. People would often go to the market to see friends, meet people from far and wide, and catch up on news. They had a separate marketplace specifically for rare goods, which nobles sought after.

People in Mesoamerica didn't much care for gold or coins. Most people traded using cacao beans (via Live Science), while the wealthy carried "axe money," according to the National Museum of American History. These small copper axe heads had a fixed value of 8,000 cacao seeds each. Clearly, they were a lot easier to transport than entire sacks of beans.

Conquistador Hernán Cortés wrote about the marketplace at Tenochtitlan (via the American Historical Association). He described a plaza, twice the size of the market of Salamanca back in Spain, where 60,000 people would buy and sell goods. There was a specific street or quarter for every kind of merchandise imaginable. Cortés describes a dizzying array of goods he saw — metals, cakes, gemstones, medicine, leather, fresh fruit — before admitting there were many more he couldn't even recognize.

Mesoamerican Ball Games

People have been playing ball games in Mexico for well over 3,000 years, according to a paper in Science Advances, using rubber balls and a long court shaped like a serifed letter I (via Britannica). These ballgames went on to become a central component of societies all across Mesoamerica, leaving behind thousands of ball courts among ruins — and the Aztecs were only too happy to carry on the tradition.

The Aztecs constructed numerous stone courts to play the ballgame, known as ōllamalīztli, featuring an alley with wall-mounted hoops, according to The Eye. The objective of ōllamalīztli was to knock the ball into the other end of the court using only elbows, knees, and hips, as detailed by Britannica. Players would wear heavy padding but, even so, the game could become quite brutal. Injuries were frequent, serious injuries were common, and deaths on the court weren't unheard of. The ballgame also held ritual significance, even being mentioned in some stories from Aztec mythology, occasionally representing the unending competition between night and day.

A modern descendent of this game, under the name of ulama, is still played in some parts of Mexico, particularly by groups of Indigenous people. It's even undergone a recent revival in popularity. According to BBC News, ball players in Mexico City are keen to make ulama popular again, paying homage to the old ritual aspects of the game by wearing vibrant Aztec-style outfits.

Aztec Philosophy

Aztec society was underpinned by a complex and well-developed school of philosophy, covering ideas like ethics, aesthetics, and metaphysics. As the Internet Encyclopedia Of Philosophy notes, their concepts were similar to those in both Western philosophy and those found in Taoism and Confuciansim.

A central piece of Aztec philosophy is the need for balance during the brief existence of life. The Aztecs had a proverb that translated meant "it is slippery, it is slick on the earth." It refers to one who lives virtuously but then falls into immoral behavior, as if slipping on mud. In the Aztec worldview, earthly life is full of suffering, and it's easy to slip up and fall into misfortune. They would strive to walk in balance on the slippery Earth, aiming for a life of morality and beauty.

Another essential component in the philosophy of the Aztecs is the concept of teotl. In the Aztec belief system, teotl is the eternal sacred force that runs through everything in the world. Constantly regenerating and shaping the cosmos, teotl is responsible for all things in nature, from the cosmic to the banal — a single principle of unity that fills everything and can never be depleted.

Philosophy in Aztec life was more than just a handful of abstract ideas. It was a set of guiding principles. Aztec philosophy was often reflected in art and poetry.

Aztec Poetry — Flowers And Songs

The Aztecs loved poetry, though they didn't have one specific word for it. Instead, they used a metaphor, "in xochitl in cuicatl," meaning "the flower, the song," according to The Sopris Sun. Aztec poetry was often about perceptions of the world and a search for meaning in a fleeting life, and an impressive amount survived the conquistadors. Aztec poems are described in detail by the book, "Ancient Nahuatl Poetry," (though it should be said that 500 years ago is not so ancient). As a European perspective though, even the author is hesitant about the translations.

Poets were highly respected members of Aztec society, and public events would always involve poetry readings. Several Aztec poets are known, like Macuilxochitzin, Tlaltecatzin, Cuacuauhtzin, Nezahualpilli, and Cacamatzin. But among the most famous Aztec poets is King Nezahualcoyotl, whose poems often grapple with the nature of life and existence, like in this verse: The fleeting splendor of the world / is like green willow trees / which, aspiring to permanence / are consumed by the fire / fall before the axe / are upturned by the wind / or are scarred and saddened by age.

Nahuatl is described as a "soft and sonorous" language, as per "Ancient Nahuatl Poetry," and the Aztecs loved singing and dancing, as well as poetry, especially at public events when the audience would often join in. The Nahuatl word for singing is cuica, which also refers to birdsong and sounds a lot like an onomatopeia.

A Culture of Artisans

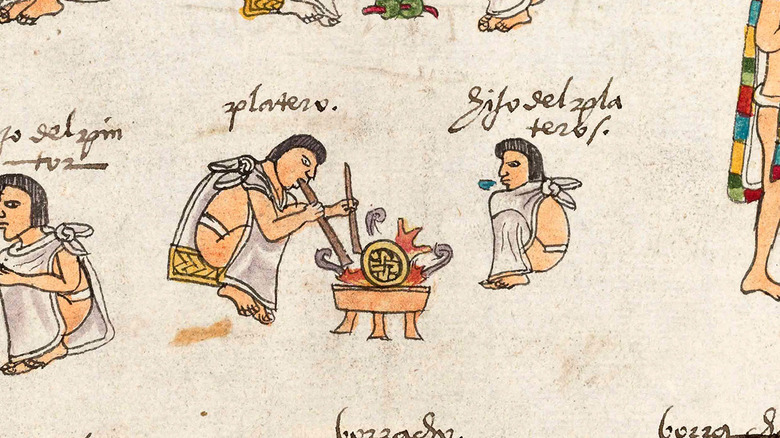

Alongside poetry and song, the Aztecs had a passion for artwork, and a lot of what remains of Aztec culture is in stone carvings, the most impressive of which were used to decorate temples. According to The Met, sculpture is a long Mesoamerican tradition that goes back to the famous colossal heads of the Olmecs. The Aztecs made thousands of sculptures, ranging from small, personal works to huge public monuments. The artworks in temples were made by only the most accomplished artisans, creating elaborate portrayals of the gods.

The Aztecs are also famous for working in gold which, as the "Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs" explains, was of exceptional quality with intricate detail. As the Aztecs didn't place any particular monetary value on gold, its main use was in jewelry and artwork. According to Live Science, the Spanish were greeted with gifts of gold in hopes it would appease them so they'd simply leave. Unfortunately, the gifts only made the conquistadors more eager to get their hands on more.

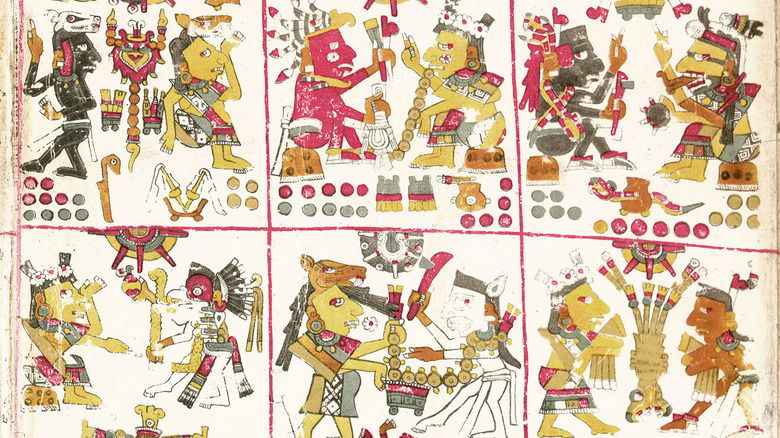

A lot of Aztec artwork was also made on paper, in codices — an old style of book. They created these using a kind of paper called amatl, made from the smooth bark of amaquáuitl (fig) trees, as per Live Science. Amatl was used for simple things like writing letters, as well as for keeping records in codices, using the Aztec writing system. The Aztecs used pictorial writing with images representing ideas.

Religion in Aztec Society

Aztec religion was an essential part of daily life and involved far more than the human sacrifice it's most famous for. Religion was important at all levels of society, with an extensive pantheon of gods, as Britannica notes. Among the most important were the god of war, Huitzilopochtli; the god of rain, Tlaloc; the sun god, Tonatiuh; and Quetzalcóatl, the feathered serpent. While it may seem like a polytheistic religion, like the Ancient Greeks, the book "Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion" explains that the many gods were actually considered different aspects of the same divinity, following the idea of teotl from Aztec philosophy.

According to Live Science, at the heart of Tenochtitlán was a sacred space known as the Templo Mayor, where a tall building with a platform flanked by stepped pyramids overlooked the entire city. A small army of priests attended the temples of Tenochtitlán, including some whose sole job was to educate novice priests. Priests had an entire social structure of their own, with the highest being important enough to count themselves among the city's nobility.

Like other Mesoamerican cultures, the Aztecs are also well known for their ritual use of hallucinogens. As a study in Neurología explains, rituals involved trances induced by peyote cactus and psilocybe mushrooms among other intoxicating substances. There was even a god, Xochipilli, whose statues are decorated with flowers from psychotropic plants, showing how important these trances were to the Aztecs, in their religion and philosophy.