Real World Things That Inspired Lord Of The Rings

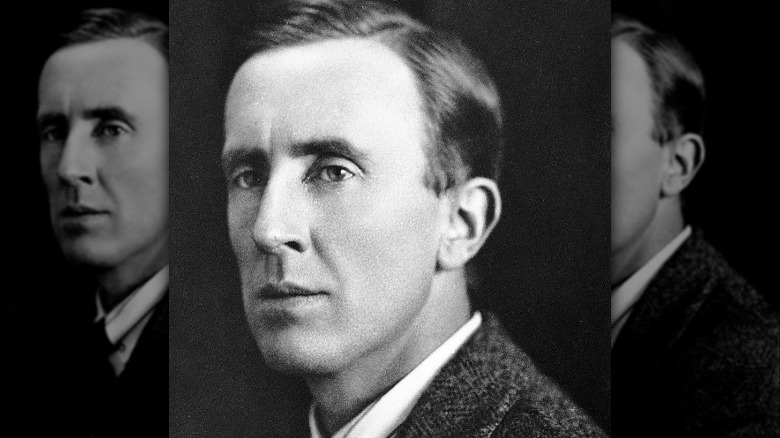

It might seem almost incomprehensible that Middle Earth and the tale of taking on the greatest evil that the world had ever seen did not, in fact, spring fully-formed from only the mind of J.R.R. Tolkien. It didn't — and there were a lot of very real-world things that all came together to coalesce into a world so fully developed that it's entirely possible to believe that it really exists out there ... somewhere.

Imagining a story is one thing, but sitting down to put pen to paper is something entirely different. It's hard, and the world has just a single person — outside of Tolkien himself — to thank for the creation of "The Hobbit" and Lord of the Rings. That's Tolkien's son, Christopher. J.R.R. Tolkien told his tales of elves and hobbits to both his sons, but according to Aleteia, it was Christopher who persuaded him to write them down. And it wasn't about sharing them with the world, or leaving them for other children and future generations, it was so he would get the details right. Christopher later wrote: "I ... was greatly concerned with petty consistency as the story unfolded, and ... on one occasion I interrupted: 'Last time you said Bilbo's front door was blue...' at which point my father muttered, 'Damn the boy,' then 'strode across the room' to his desk to make a note."

So where did all this inspiration come from? From close to home... and very far away, indeed.

A cursed ring

At the center of Lord of the Rings is, of course, the One Ring. Why a ring? Some scholars suggest it wasn't a random choice at all, and point to one particularly ancient ring that may have influenced Tolkien's epic quest. It was discovered in a farmer's field in 1785. The massive gold ring was inscribed with the text "Senicianus live well in God," and it was ultimately linked to an ancient Roman site called the Dwarf's Hill — 100 miles away. The connection came years after the ring was found, when a tablet was discovered at the hill. It bore a curse reading: "Among those who bear the name of Senicianus to none grant health until he bring back the ring to the temple of Nodens."

Just the idea of a cursed ring isn't enough to make a connection to the One Ring, but according to The Guardian, an archaeologist working on the site in 1929 consulted with an Oxford professor to try to find out more about the names on the ring. That was, of course, J.R.R. Tolkien, and it's suggested this was what sparked the idea of an ill-fated ring.

As the Independent says, Tolkien documented his research into the ring and Nodens, who was the god of the local temple. Tolkien not only visited the temple, but within a year of being contacted about the ring, he started writing his epic.

Sarehole and Sarehole Mill

Born in South Africa and living much of his life in England's highly industrialized Birmingham, it's perhaps not entirely surprising that Tolkien had a soft spot for the countryside. He rarely gave interviews, but when he spoke with The Guardian in 1966, journalist John Ezard recalled that he had wanted to talk about the little country village called Sarehole, where he had lived from the age of four to eight.

"It was kind of a lost paradise," he said. "There was an old mill that really did grind corn with two millers, a great big pond with swans on it ... I could draw you a map of every inch of it. I loved it with an intensity of love that was a kind of nostalgia reversed."

Life was just as idyllic as the surroundings, especially when compared to what lay ahead. Little Tolkien was learning about dragons and studying languages at his mother's knee, when just a few years later, she would be gone and Tolkien would be sent to a very different place. He'd carry Sarehole with him, though, using it as the basis for the Shire, and the village's residents as a template for the hobbits. The Sarehole Mill still stands, and visitors can take a walking tour throughout the area, and pass Tolkien's one-time home as they do. The Shire's mill was, of course, a starting point for everything — and for Tolkien, the mill's real-life counterpoint was an anchor into the idyllic.

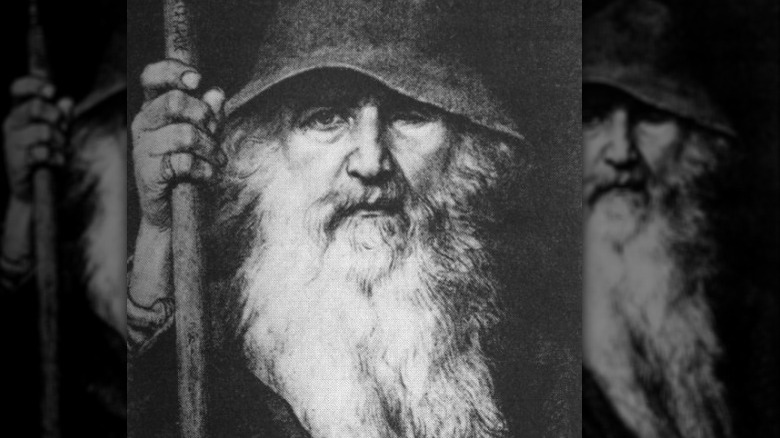

Odin

Lord of the Rings is a saga on a grand scale, and Middle Earth is a vast land with a deep-rooted history: The very idea of such a thing came from Old Norse literature and mythology. According to the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, the old Norse sagas not only filled his academic life but captured his imagination in some pretty specific ways — particularly in the creation of Gandalf.

Odin was the prime deity of Norse mythology, and this isn't the Odin of the Marvel movies. The original Odin, says World History, was a wildly powerful being that created the world, and ruled over the domains of the dead, magic, and war. Even though he was the god of warriors, he was never described as actually looking like an armored warrior. Instead, he's a grizzled old man clad in a long robe and a wide-brimmed hat, sporting a long beard. Sound familiar?

In one letter, Tolkien described Gandalf as his "Odinic wanderer," an entity from a different — and higher — realm who travels through Middle Earth looking almost exactly like his Norse counterpart. (Odin, however, only had one eye.) Gandalf even had the same network of animal companions, and just like Odin, he had ravens and eagles keeping him informed of distant happenings.

Bag End

J.R.R. Tolkien's inspiration for the Shire aside, it's worth talking about the place where his greatest adventures both began and ended: Bag End.

Bag End was the name of Bilbo and Frodo's home, and according to Tolkien researcher Andrew H. Morton (via the Tolkien Library), it was a very real place. Tolkien's aunt, Jane Neave, lived in a country home properly called the Dormston Manor Farm, but after doing considerable research on the property, she reverted back to calling it by the original name of Bag End. Tolkien stayed with her for a spell in 1923 — he was recovering from a severe illness — and although his written references to it are singular, Morton suggests that the fact that the history of the place went all the way back to the Anglo-Saxon era would have had a great impact on the young Tolkien.

Interestingly, Morton also draws another comparison between Tolkien's aunt and the non-traditional Took family. She was a popular and beloved member of the community, but at the same time, she was also forward-thinking and "slightly mysterious," which Morton says is "more than a little 'Took-ish.'" Bag End might have belonged to the Baggins family, but Aunt Jane? She was 100% Took.

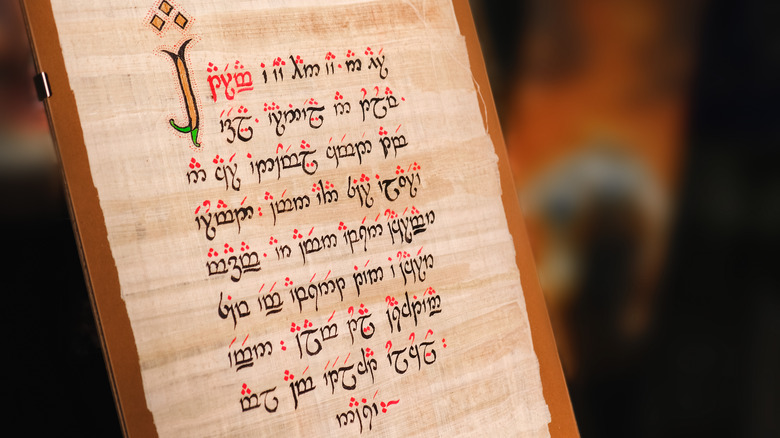

Wales and their language

J.R.R. Tolkien was famously fascinated by language, and when it came time to invent entire languages for his fantastic Middle Earth, he didn't just mash some letters together and call it a day. Fred Hoyt, a linguistics researcher from the University of Texas at Austin, explained to The Guardian: "They are invented languages but they are completely logical and they're linguistically sound."

There's a good reason for that: Tolkien used real-world languages for the building blocks of the tongues of Middle Earth — and that included using Welsh to build Sindarin, the language of the elves. Tolkien was fluent in the modern version of the language and taught the medieval version, and according to research done by Cardiff University (via the BBC), Tolkien used the language as a guide for how words sounded and were structured — so much so that native Welsh speakers watching the Lord of the Rings movies can recognize bits and pieces of what's being said.

It's really not surprising that Welsh plays such an important role in Tolkien's work. He once described it as "... a hint of a language old and yet alive. It pierced my linguistic heart."

World War I

J.R.R. Tolkien left the U.K. in June of 1916, says We Are the Mighty. Less than a month later, he was in the middle of one of the war's bloodiest battles, and during that battle — over the Somme River — he lost his best friend. He remained in the thick of things until trench fever saw him pulled from duty and sent home, just days before the end of the war.

Tolkien condemned the idea that there were any direct comparisons that could be made between his work and the real-life war, but some of those who knew him best say differently. His grandson, Simon Tolkien, spoke with the BBC in 2017, and confirmed that it was rare that his grandfather would say anything about his experiences at war. But when Simon — who has himself become a prolific writer, with much of his work focused on the war — re-read Lord of the Rings with WWI in mind, the inspiration was clear.

It was perhaps most vivid in the descriptions of Mordor and Isengard, reminiscent of the almost invariably deadly wasteland that was No Man's Land. The industrialized orcs and the ever-advancing machinery of Sauron had clearly been inspired by the increasingly mechanized war machine, but it wasn't all bad. In the brotherly devotion of Frodo and Sam, Simon saw the unbreakable bonds made between those who served together in battle.

The Somme

If J.R.R. Tolkien took terrible inspiration from his experiences during World War I, there's one day, in particular, that's worth looking at alone: July 1, 1916. The battle of the Somme was, says The New York Times, the deadliest day in Britain's military history, and by the time it was over, 19,240 soldiers were dead. Tolkien was there with the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers and was acting as a communications officer — a job that made them particularly vulnerable. The offensive dragged on and on, and in between combat and enemy fire, he started putting together his stories of Middle Earth — including the most horrible place of all, the Dead Marshes.

It's right up there with Mordor itself, and as Frodo, Sam, and Gollum cross through the greasy, muddy, mucky, marshes, Frodo looks into the water and sees them: "They lie in all the pools, pale faces, deep deep under the darkwater. I saw them: grim faces and evil, noble faces and sad. Many faces proud and fair, and weeds in their silver hair. But all foul, all rotting, all dead." Gollum agrees: "All dead, all rotten. ... There was a great battle long ago..."

The Somme offensive wouldn't end for another five months, and when it did, 1.5 million dead lay along the French river. Among them were several of Tolkien's close friends, and it's a question that has to be asked: In his mind's eye, did Tolkien see Ralph Payton and Robert Gilson among the Dead Marsh's faces?

PTSD/Shell shock

In 1960, J.R.R. Tolkien wrote that "Personally I do not think that either war ... had any influence upon either the plot or the manner of its unfolding." Save, that is, the comparison between the Dead Marshes and the body-littered battlefield of the Somme. But an article written for Mythlore suggests there was something else there, too, and it was something that many people just didn't talk about much. That's shell shock, and today, it's called PTSD.

By the end of the series, it's obvious that Frodo's not the same hobbit who left the Shire on a quest to destroy the One Ring. While countless other works have heroes and heroines that just sort of brush the dust off their shoulders and go on like nothing happened, Frodo has clearly been deeply changed by what they've been through. He's described as often "silent," and "ill at ease," saying of his return home: "Though I may come to the Shire, it will not seem the same; for I shall not be the same."

Later, Frodo withdraws from his old community, speaking of inconsolable sadness and wounds that would never heal. He suffers from flashbacks and overwhelming guilt, finally opting to leave his once-beloved Shire for the Undying Lands. It's argued that all of these feelings would have been familiar to a Tolkien who survived the war when so many others had died, and who had returned to find himself looking on a place both familiar and unfamiliar at the same time.

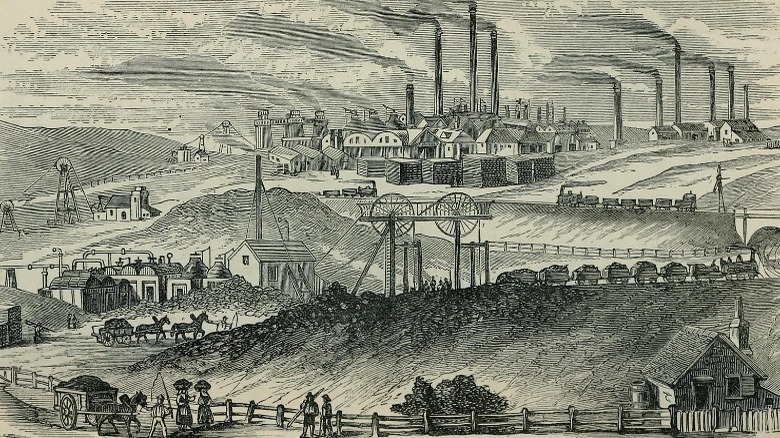

The Black Country

A charred and blackened land, filled with little more than coal, smog, and the sound of industry: Forges, foundries, coal mines, collieries, and ironworks. Lit by red-hot fires at night... and a barren, black, dirty wasteland any time of the day. Sounds like Mordor, right? It can also be applied to a swatch of the UK once known as the Black Country.

"Mordor" in the Sindarin tongue translates to "black lands," and according to the BBC, the Black Country is a term used to describe part of the West Midlands. While there are no agreed-upon boundaries, it's particularly the area west of Birmingham — which is where Tolkien spent a good part of his life. From the mid-19th century until fairly recently, it was the home of thousands of iron- and metal-working factories and foundries. And the landscape really was bleak, once described by an American Consul as "Black by day and red by night." Compare that to Tolkien's description of Mordor: "It is a barren wasteland, riddled with fire and ash and dust, the very air you breathe is a poisonous fume."

Carol Thompson was the historian behind a 2014 exhibition on Tolkien and the influences his childhood had on his writing. She argues (via the BBC) that the Black Country as an influence for Mordor went deeper than just the appearance of the blasted lands. The industry that had grown up there was going to spread, and as it spread, it was going to devour and destroy the countryside that he'd held so dear.

J.R.R. Tolkien himself

Authors putting themselves into their books is nothing new, but what is cool is how influenced by J.R.R. Tolkien's own likes, dislikes, and personality the hobbits were. In 1967, Tolkien spoke with The Sunday Times (via The New York Times) for a piece called The Prevalence of Hobbits, and it's a pretty neat look into what went on behind the curtain, so to speak. Fans are familiar with hobbits: They like parties, fireworks, food, and tobacco, and they're really not too fond of going on adventures. And Tolkien? It turns out, that's all him.

Tolkien famously wrote the word "hobbit" on a particularly boring exam paper, and fast-forwarding a bit saw him writing in his home garage-turned office. It was there he had his collection of tobacco tins, and it was also there that he was happy to have a great view of the Oxford United football pitch — and even better, the fireworks they occasionally set off. He admitted: "I run to the window every time I hear a whoosh."

Tolkien himself had a very hobbit-like personality, too, saying: "Most of the time I'm fighting against the natural inertia of the lazy human being." He loved his garden, and really, really loved simple meals of cheese, pastries, and beer — "none of that cuisine mystique." A lot that he wrote about the hobbits could, in fact, have been written about himself.

Fafnir and the dragons of mythology

Dragons have been around for a long, long time — according to World History, the oldest known representation of a dragon dates back to somewhere between 4500 and 3000 BC, and Inner Mongolia's Hongshan culture. It might be tempting to see J.R.R. Tolkien's titular beast as just one more in a long line of dragons, but the Smithsonian says there are a few specific dragons that inspired the gold-hoarding Smaug. Tolkien had grown up as a child in love with the very idea of dragons, once writing, "I desired dragons with a profound desire. Of course, I in my timid body did not wish to have them in the neighborhood. But the world that contained [them] was richer and more beautiful, at whatever cost of peril."

There were two dragons, in particular, that got folded together to create Smaug. First, there was Fafnir, the antagonist of a Norse epic who was obsessed with hoarding gold — and warned anyone and everyone that if anyone were to touch his treasure, it wouldn't be long before they were in the sort of deep-fried, crispy state that would definitely keep them from touching pretty much anything else.

And then there was the dragon from Beowulf: Slain by the hero of the poem, the dragon doesn't even get a name. The treasure-hoarding beast who goes on a rampage over the theft of a single gold cup captured Tolkien's heart, though: "I find 'dragons' a fascinating product of imagination."

The Abyssinian Empire

As the Tolkien Library notes, it can be tough to discuss the inspirations for J.R.R. Tolkien's work, because he often claimed that the stories of Middle Earth came to him as if they'd already been written. That's led literary scholars and historians on something of a wild goose chase, and some theories are more solid than others. It's Michael Muhling who puts forward the compelling argument that at least some of the landscape of Middle Earth came from the 3,000-year-old Abyssinian Empire. Located in what's now Ethiopia, there are some fascinating similarities — all combined with the fact that the area was in the news at the time Tolkien was writing, thanks to a 1935 invasion by Italy.

There are a ton of things that will sound familiar: A group of people who were known for their prowess on horseback, an area threatened by seemingly unbeatable enemies, and even an ancient stelae of Axum, a real-life version of Isengard. Did the Africa-born Tolkien turn the real-life city of Roha into Rohan, the real-life Gondar into Gondor?

There are a few other interesting facts behind this one. Muhling says that all the references that can be traced to ancient Abyssinia are missing from "The Hobbit," which was written before the international incident that put the ancient nation on the map again. It can be argued that the history of Abyssinia provides the bones to Lord of the Rings, and yes, Tolkien's own library did include books on the ancient land.