The Untold Truth Of Fugazi

Many people might think they don't know anything by the band Fugazi, but when they hear the opening funky, throaty, floaty bass notes, hit-the-ground-running drumbeat, and prickly guitar of their generally best-known song, "Waiting Room," by the time the vocals start, they'll be singing along: "I am a patient boy. I wait, I wait, I wait, I wait," and then say, "Oh! That's who does that song?"

Fugazi was a college radio darling by the early '90s; considered underground at the time, much like most other bands your weird friend back then lovingly put on a mix tape for you, their audience and familiarity have grown exponentially in the decades since. But there are a lot of interesting things about the post-hardcore band from Washington, D.C. that aren't widely known.

Britannica tells us that bassist Joe Lally, drummer Brendan Canty, and vocalists-guitarists Guy Picciotto and Ian MacKaye formed Fugazi in 1987 after the demise of each members' many bands before. Their ages ranged from 21 to 25 years old, and they bonded over shared anti-racist and anti-sexist political views, a lack of interest in substance use of any kind, and their love of the explosive hardcore music scene in their D.C. home. Over the course of the next 16 years, they would release the studio records "Repeater," "Steady Diet of Nothing," "In on the Kill Taker," "Red Medicine," "End Hits," and "The Argument," and be the subject of director Jem Cohen's 1999 documentary, "Instrument." This is the untold truth of Fugazi.

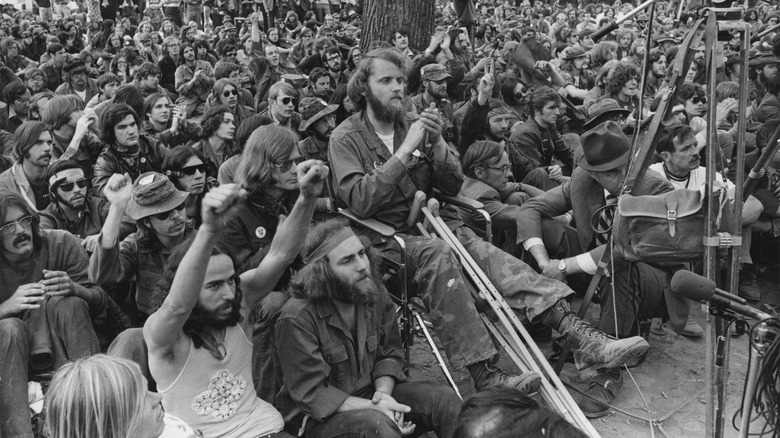

Fugazi Wouldn't Have Existed Without the D.C. Hardcore Scene

In an interview with Psychic Gloss, Guy Picciotto credited Georgetown University radio station WGBT with first exposing him to punk rock. The station was on Georgetown property and technically owned by a conservative religious organization affiliated with the university, but its day-to-day operations had been taken over by more politically forward-thinking people. The religious organization eventually caught wind of this and closed the station.

"The first punk rock show I saw was when I was thirteen and it was a benefit which was more of a protest against the closing of that station," Picciotto said. "At that show I saw [fellow D.C. band] Bad Brains and my future bandmate Ian MacKaye ..."

That Bad Brains show planted the seeds of what would become one of D.C.'s other most feted hardcore bands, Minor Threat, fronted by the aforementioned MacKaye, who would subsequently go on to form Fugazi with Picciotto. But before then, they would play with several other bands, as would their future bandmates Brendan Canty and Joe Lally.

Picciotto elaborated on the genre's significance: "I think a lot of people look back on [hardcore] now and see this orthodox or rigid style of music, but the shapes that everyone can look at now and see as a pattern, when these people were starting to make that music it had no formulaic shape yet so it felt incredibly radical at the time ... I really wanted to be a part of it."

Their Name Came from Vietnam War Veterans

Once the band solidified, they needed a name that would hit as hard as their music and politics, yet be unfamiliar enough that people wouldn't get pre-conceived ideas. In a 2013 interview at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., Ian MacKaye said that around that time, he was reading "Nam," a book of recollections of Vietnam War veterans (MacKaye cites the author as Michael Herr, but "Nam" was compiled by Mark Baker). He said, "[I saw] the word fugazi ... I thought, 'what is that?' And I went back to the glossary at the back of the book, and it just said 'a f***ed up situation.' And, I thought that was a great term!" He said that he thought it must be some kind of acronym but couldn't find any further information. MacKaye said, amused, that people's guesses at what the word meant ranged from a Japanese motorcycle to an Italian dessert.

He said that in 1997, Fugazi were playing in Singapore, and after the show, a young woman named Venita and her brother approached him. The brother asked MacKaye what Fugazi meant, and before he could answer, Venita said "F***ed Up, Got Ambushed, Zipped In" (presumably, into a bodybag). It was the first time he'd heard what the acronym stood for. He asked her where she'd heard it, and she said she'd found it while researching their name. "Well, that's incredible!" he responded.

Their Shows Were Always $5 and All Ages

By the time grunge music broke in the early '90s, Fugazi was already well-known, adored, and name-checked by many formerly obscure artists who had since become wildly successful. The Washington Post reported that Kurt Cobain, Courtney Love, Michael Stipe, and Eddie Vedder were among their fans and friends, and as a result, there was quite a buzz about them in the music business and elsewhere. They could have gotten the riches and fame that many young musicians long for, but they remained loyal to their principles, one of which was never charging more than $5 for entrance to their shows. "We try to make it as easy as possible for people to come see us and we try to make it as easy as possible for people to leave if they don't like it," Guy Picciotto said in 1993. "Five dollars is not going to bust anybody."

In addition to insisting on affordable ticket prices, Fugazi refused to play venues that required a minimum age, because that would also limit their audience. This stemmed from the members' own influential experiences with live shows at young ages in unusual spaces, and their commitment to inclusivity. Washington D.C. music critic Chris Richards, who played in his own punk band in the '90s, told The Guardian, "At 15, the bar for entry was zero. That blew me away. You just show up and you're part of it. It cemented in my young mind that music and community are inextricably linked."

Dischord Records was truly a grassroots label

In 1980, ambitious teenagers Ian MacKaye, Nathan Strejcek, Geordie Grindle, and Jeff Nelson founded the Dischord label initially to release a record by their band, the Teen Idles, MacKaye told The Guardian. They pressed 1,000 copies of the record and used recycled cardboard, scissors, and glue to create the sleeves. The band broke up later that year, but MacKaye and Nelson have kept the label going to this day.

The punk rock scene of D.C. had exacting standards when it came to music and money. MacKaye said, "Releasing a record, and monetizing music, some people looked at a little askance. So we declared any money made would go to documenting other bands." To keep Dischord operating, MacKaye held down three jobs and kept the practice of taking cardboard from people's trash to make their label's record sleeves going. Dischord was run entirely by volunteers, and no one got paid for their work until the label had been around for eight years.

And, unlike major labels, they've never used contracts. Kim Coletta, bassist for the former Dischord band Jawbox, explained the simple philosophy to SPIN magazine: "Ian always told me that [contracts are] unnecessary, because if bands are happy, they'll stay on your label." The basic agreement is that bands get a small advance to record and produce a cover, and once that money and the cost of production are recouped, the band and Dischord split the profits.

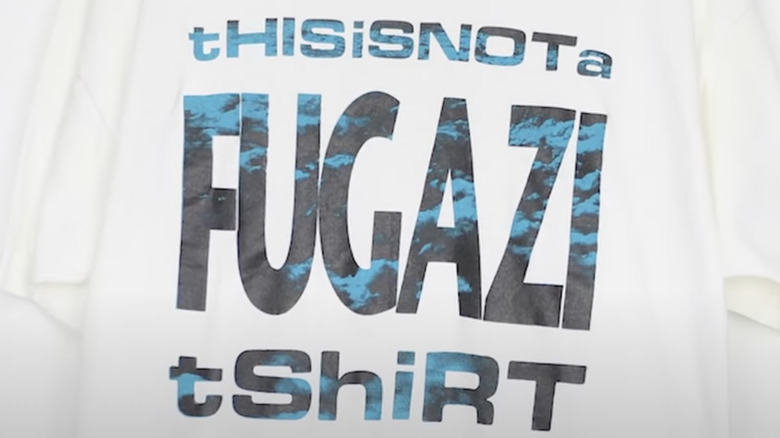

You Won't Find Any Official Merch

Fugazi's commitment to doing things their own way extended into their refusal to sell any kind of merchandise other than their recordings. In an interview with Monster Children, Guy Picciotto explained, "Our idea back when we were touring was that we didn't want to carry merchandise, and we were also reacting against the idea that we had to carry merchandise ... It also ended up being kind of cool because we encouraged people to make their own shirts."

But in addition to individual fans, bootleggers tried to get in on the shirt game. In the book, "The Art of the Band T-Shirt" (via Culture Creature), Ian MacKaye said how time-consuming it was to follow up on leads of bootleggers and demand they stop producing the unauthorized t-shirts. One such call led to a conversation that ended with the bootlegger acquiescing. "A friend at a record store alerted me to the 'This is not a Fugazi t-shirt' shirt," MacKaye said, who then traced the shirt back to a Boston t-shirt company previously given a warning. "I called him up and said, 'Okay, you're funny and you're creative, so let's see how creative you are with accounting.' I asked him to choose an organization doing good work in his community and give them what would amount to the band's royalty for the shirts." Apparently it worked, as the company regularly donated to a local women's shelter until it closed its doors.

Ian MacKaye's Grandparents Contributed to Fugazi's Discography

Fugazi didn't exactly have a cushy setup or living situation along the way, even after their first two successful and groundbreaking studio records. Of course, they started in what had come to be known as "Dischord House," the headquarters of the record label and the place where Ian MacKaye lived. But as the label's catalog and mail-order business boomed, its space shrank, and the band had to figure out another place to practice and record.

Guy Picciotto told Pitchfork in 2002 that after Dischord House's basement couldn't hold them anymore (the label needed the space for storage and shipping), the band relocated to Mom and Dad Picciotto's basement, then bassist Joe Lally's basement, and then ... off to grandmother's house they went.

MacKaye's grandparents took enough pity on them to lend their Connecticut house, where the band conjured and recorded 1993's "In On the Kill Taker" and 1995's "Red Medicine." Picciotto said of their idyllic time there: "We would set up in the living room, wake up, have breakfast, play for four hours, go into town ..." The band would spend their days at the batting cages, cooking dinner, then playing all night. "We had our eight-track set up and all the songs for [those 2 records] were kind of crafted in that space," Picciotto said.

Nina Simone was a big inspiration

Fugazi was touring Australia in 1996 when Ian MacKaye caught pneumonia. As he relayed to the Washington Post, the illness collapsed one of his lungs, and he landed in the hospital for 19 days. It nearly killed him. To keep his sanity, he listened to CDs, one of which had the song "Compensation," by Nina Simone. "I listened to this and it just pulled me through. ... I kept hearing the music like it was speaking to me in a way that made me happy, made me feel like it's worth fighting through this thing."

The song is both ethereal and minimal, and the lyrics pack a punch, especially for someone confronting their own mortality. The last lines in the song are (via Genius): "... Sung with such faltering breath / Oh, oh, oh, the Master in His infinite mercy / Offers the boon of death." Pretty relatable for an ethics-driven musician fighting for his life in a hospital far from home.

MacKaye also related to Simone's dedication to doing her music strictly on her terms. "She's such a badass," he said.

MacKaye was a guest host at 2009's Maryland Film Festival in Baltimore. Carrying his love of Simone forward, he told the Baltimore Sun that he had chosen to present a short 1992 documentary about her called "Nina Simone: La Legende." He said he had been thinking of something more brutal and antiwar but instead opted for a celebration of "humanity, creativity, life!"

Their Music and Activism Inspired an Art Exhibition

In 2019, graphic designer and Fugazi fan Carni Klirs presented the exhibition, "Visualizing Fugazi," by combining his artist's eye with extensive data on the band to create colorful infographics, along with complementary ephemera like fliers, fanzines, and photos chosen by curator John Davis. WAMU reported that Klirs had accumulated the extensive data by going through the band's meticulous records of live shows and crowd attendance, as well as their extensive digital archive of shows. The infographics include a map of the unconventional venues (noting which ones still exist) that the band played in keeping with their all-ages commitment, their activism and fundraising numbers, and a "Fugazi Family Tree," which shows Fugazi's members' connection to about 5,300 bands. "This is my fanzine," the artist said, "an obsessive documentation of a band I love, told through their own data."

The Washington City Paper explained that Lost Origins Gallery in Northwest D.C. was the perfect spot for the exhibition, as its owner, Jason Hamacher, was in a bunch of bands featured in the Fugazi Family Tree. Klirs himself had been going to punk shows in D.C. since the early 2000s, performing in various bands, and operating a recording studio in the city. "Visualizing Fugazi" was a true labor of love and product of its beloved environment.

Ian MacKaye Saved a Fan Letter from 14-Year-Old Dave Grohl

Ian MacKaye saved nearly everything from his music career, including fan letters. In 2015, he came across one particularly unusual letter from a 14-year-old baby Foo Fighter, Dave Grohl. Grohl told NME that MacKaye had emailed him, telling him of the discovery. "It was this little letter that I sent him ... I think I was maybe 14 and I wrote Dischord Records a letter because I wanted someone to release my band's demo tape, we were called Mission Impossible."

SPIN showed a fragment of the letter, which Grohl had tweeted about. "Look what my hero Ian MacKaye (Minor Threat/Fugazi) just found." The fragment shown read "... good thrash so I was wondering if you could give me some numbers of people to get in touch with. It would help. Thanx. David Grohl," along with his phone number and the caveat to call between 3-10 p.m., presumably because he had school and lived with his family. Aww! Even future rockstars had to live by certain rules at some point.

They Didn't Abide Misogyny

The fact that Fugazi's audience skewed largely male makes their vocally anti-misogyny stance all that much more significant. The Guardian reported that it was during archly conservative 1988 America that they released a song called "Suggestion," which Ian MacKaye wrote about some heartbreaking experiences a female friend of his had told him about. Verses like "Why can't I walk down a street, free of suggestion?" and "Is my body my only trait in the eyes of men?" speak of the experiences women often face.

The feminist punk community's reaction was mixed, with the main criticism being that it wasn't really a man's place to sing from a woman's perspective. Yet, the song's importance remains, because to say that all-male bands in the hardcore scene generally didn't even glance at this issue would be an understatement. Bikini Kill and the Julie Ruin frontwoman Kathleen Hanna explained to SPIN her complex reaction to the song: "I have issues with Ian MacKaye — who I love — singing as if he was a woman. But that song changed my life, because it was the first time I ever heard a man singing about something that was predominantly a woman's issue ... It's not about being perfect, it's about opening the conversation." Unfortunately, the song remains as relevant now as it was then.

Their Sound Guys Recorded Over 800 Shows

In 2011, Fugazi unveiled the first 130 shows in their digital archive, an exhaustive collection of their concerts from 1987 to 2003, and they've been adding to it ever since. In an interview with Pitchfork, Ian MacKaye explained a friend named Joey Picuri did their sound and started recording the shows from the mixing board. Thus began what would grow into an over-800 show archive of recordings, meticulously documented. The archive is available for download ($5 per show) at the Dischord website.

Yet, for all the shows they did get the recordings of, there's one that they didn't, and it haunts them. As NPR details, on the first date of their 1993 Australian tour, Picuri hooked up a brand new portable DAT machine to the board to record the show per usual. But, by the end of the night, someone had stolen the recorder with the tape inside, and to this day, they haven't gotten it back. "The equipment was replaceable, but the tape was one of a kind," Guy Picciotto told NPR. "Not that the show was super-epic or notably awful — it's just that it's like someone tearing a page out of your diary and throwing it in the trash. It's just wrong." Picciotto also said that if the person who stole it just returns the recording, they won't ask any questions or press any charges.

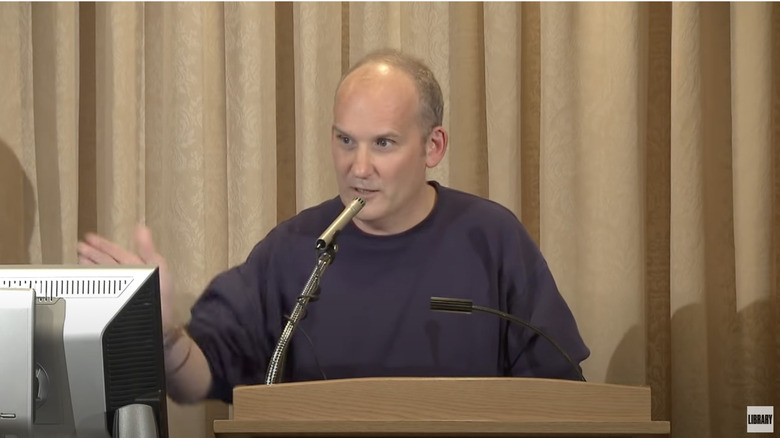

Their Archived Materials Got the Library of Congress' Interest

Another D.C. organization, the Library of Congress, also took interest in the Dischord and Fugazi archives. They hosted an event in 2013 centered on citizen archivists, and Ian MacKaye was a guest of honor. Butch Lazorchak wrote for the Library of Congress "The Signal" blog, "MacKaye has documented music coming out of the Washington, D.C. underground for the past 30 years. Much of the music and art he's compiled is not being comprehensively addressed by major collecting institutions, but that's not unusual."

MacKaye's lecture at the LOC touched on many points. SPIN printed some of their favorite highlights from the talk, including his own beginnings as archivist: His grandmother, Dorothy MacKaye, wrote a column about marriage advice for the Ladies' Home Journal. She'd record conversations of couples speaking to counselors and write about them. She then extended her recordings into her own world, informally documenting her life, and her grandson would come across the invaluable historical recordings years later. "There was just something about the documentation of these moments that were really nice, really interesting things," he said.

They haven't broken up

On Fugazi's own website, they don't declare themselves broken up, but rather "on indefinite hiatus since 2003." In an interview with Approaching Oblivion, Ian MacKaye explained that with everyone's growing families and aging parents, there just wasn't time anymore. "I coined the indefinite hiatus term specifically because I thought it was absurd to break up, it wasn't a circumstantial issue, it wasn't that anyone did anything wrong ... It is entirely possible that we will play again and it's also possible that we won't."

Drummer Brendan Canty added in an interview with Louder Sound, "I don't see us going back to Fugazi ... Then again, we never put it out of our heads, really. A lot of the reasons why we stopped were logistical because of kids and things like that. It was mostly kids and death."

They have never stopped making music. Per the Dischord website, among many other projects throughout the years, Canty re-joined forces with bassist Joe Lally to form The Messthetics with Anthony Pirog on guitar, and Lally also reunited with MacKaye to form the band Coriky with drummer Amy Farina.