The Tragic Truth About The Great Boston Fire Of 1872

The Great Boston Fire of 1872 was unlike anything the city had ever experienced before. Although the city had seen its share of fires, this blaze burned the city with a vengeance against a perfect storm of poor conditions. The worst part was that the disaster wasn't entirely unavoidable. During the 19th century, several cities experienced devastating fires and although they had the chance to learn from one another, there was often little done to prevent subsequent disasters in other cities.

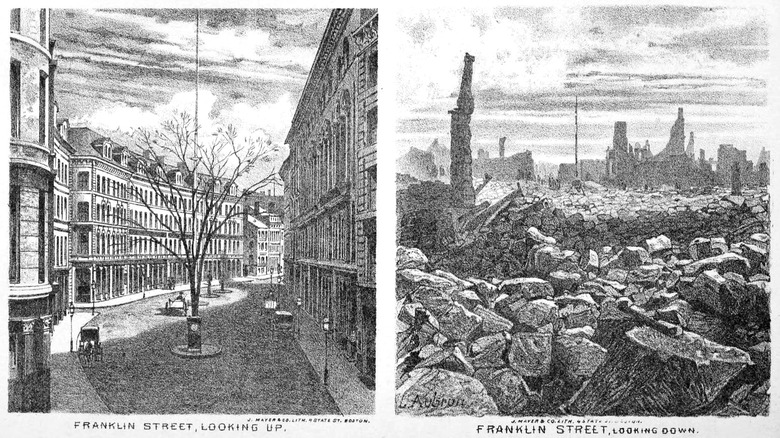

Burning from the Common all the way to the waterfront, the Great Boston Fire of 1872 laid waste to the city. Although from the ashes rose what is now Boston's financial district, the city was forever changed by the fire. Some reports even state that land values in the area skyrocketed after the fire, a phenomenon not typically seen in the aftermath of fires.

For some, the Great Boston Fire was a wake-up call to push for a wider set of building codes to protect against fires in cities nationwide. But despite the efforts of Fire Chief Engineer John S. Damrell, who sought to institute a national set of building regulations, a national push for building codes wouldn't come for another 30 years after the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904. This is the tragic truth about the Great Boston Fire of 1872.

Boston in the 1870s

By the mid-19th century, urban growth in Boston was accelerating and the city raced to keep up. The Boston shoreline was extended during the beginning of the 19th century and by 1870, the reclamation of Back Bay had created the largest landfill in the world, according to "Architecture After Richardson." Much of this urban growth was also financed by the riches made during the colonial period from the trade of sugar, rum, and enslavement.

Think Progress writes that the cities of Boston, New York, St. Louis, Buffalo, and Chicago all increased population growth after the Civil War by several hundred percent. Many of the municipal boundaries were also grown through annexation after the Civil War, according to "The Boston Renaissance," edited by Barry Bluestone and Mary Huff Stevenson, which states, "Roxbury was annexed in 1868 [and] Dorchester in 1870." Brookline was almost swallowed into Boston as well in 1873 but they resisted and remained their own town.

But as the city grew, the narrow streets of Boston became more and more crowded with buildings. And despite the rapid development, some items, like water mains, hadn't been upgraded, according to the Boston Fire Historical Society. And as the equine flu spread through the American horse communities, cities like Boston found themselves relying on manpower in a way they hadn't in years.

The basement of a warehouse

The Great Boston Fire started around 7 p.m. in a basement of a dry goods store at 83-85 Summer Street in downtown Boston on November 9, 1872. Although the cause of the fire is unknown, it's believed that a coal spark from a steam boiler ignited the dry material in the basement that was stored next to the boiler.

According to the New England Historical Society, the fire burned up through the wooden elevator shaft, located in the center of the building, which allowed the fire to quickly spread and within half an hour the building was completely engulfed in flames.

Before long, the fire was working its way through the entire commercial district. History Daily writes that by midnight, the fire had taken over a five-block area, and by the early hours of the morning, it had reached the waterfront. The fire became so hot that some buildings "actually melted in addition to burning."

Firefighters were even brought in from surrounding New England states like Connecticut and New Hampshire, according to the Boston Public Library, to help put out the fire. The fire was so large that even sailors on the coast of Maine could reportedly see the fire.

How did the fire spread?

There are several factors that contributed to the Great Boston Fire spreading so quickly. The Boston Public Library writes that the wooden mansard roofs, which were popular in the area, provided some of the main fuel for the fire. In addition, because of the narrow streets, the fire was able to spread incredibly easily from street to street. According to Springfield Museums, the fire was also able to spread quickly from roof to roof because merchants weren't taxed on inventory in their attics, and as a result, these wooden rooftop areas often contained a great deal of dry flammable goods.

History Daily refers to it as a "perfect storm of influences." In addition to the narrow streets and wooden buildings, "there were few building codes in Boston, and those in place weren't enforced." And because many building owners over-insured their buildings against fire damage, according to the New England Historical Society, they put little effort into making their buildings safe from fires.

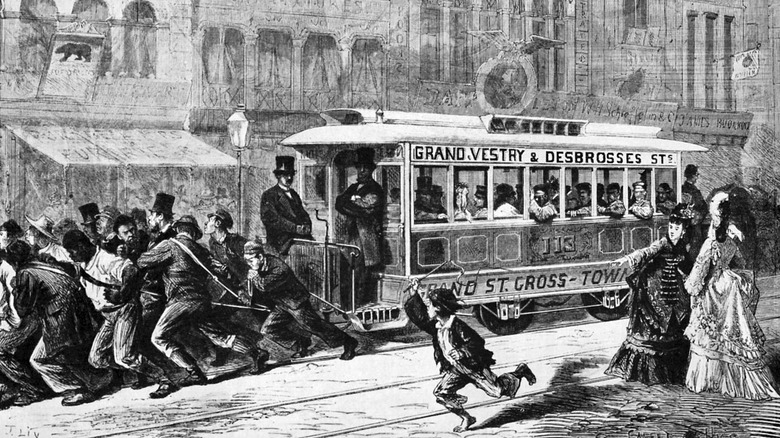

There was also the issue of the recent equine flu outbreak, which weakened and killed many horses during the late 19th century. Smithsonian Magazine writes that with many horses too sick and weak to pull equipment, Boston firefighters had to pull their heavy pump wagons themselves. However, the Report of the Commissioners appointed to investigate the cause and management of the great fire in Boston concluded that if the horses were healthy, the firefighters might've only saved about three minutes of time.

Boston's fire alarm boxes

A particular feature of the Boston fire alarm system at the time also contributed to the Great Boston Fire. Although the city installed a fire alarm system in 1852, History Daily writes that the fire alarm boxes were locked due to the issue of false alarms. As a result, only a few citizens in each neighborhood were trusted with keys.

Unfortunately, on the evening that the Great Boston Fire began, the key holders couldn't be found. As a result, the fire alarm wasn't set off until around 7:25 p.m. and it took until 8 p.m. for Boston's fire engines to arrive at the burning building, according to the Boston Public Library. Even though all of the city's 21 engine companies arrived, they quickly realized that the fire at hand was quickly burning out of control. Another factor that didn't help was the low water pressure from the fire hydrants which made it incredibly difficult to put out the flames at the tops of buildings.

The Boston Fire Department tried to telegraph for help, but it took some time for assistance to arrive because the telegraph offices had already closed for the evening, according to the City of Boston.

Over 15 hours of flames

The fire lasted over 15 hours, with some reports even claiming that it went on as long as 17 hours. Boston Chief Engineer John Damrell, in a speech later given to the Boston Veteran Firemen's Association, stated that the Great Boston Fire was the "most terrific engagement by the fire department for superiority over the fire fiend ever recorded in the annals of the city."

Because the fire was mostly contained in the commercial districts, many people came out simply to watch the fire burn. Others brought their possessions out in the fear that their homes were next.

It's estimated that as many as 100,000 people came out to watch the Great Boston Fire. The Boston Public Library writes that in addition to spectators the streets also became filled with merchants trying to save their wares. In her book, "The Great Boston Fire," Stephanie Schorow writes that watching fires was actually a common form of entertainment at the time. During the night, the Great Boston Fire took on a carnival-like atmosphere with many drunk spectators gawking as they watched the buildings of burn. One liquor outlet even started giving away its alcohol, lest it be burned up by the fire.

Despite the best efforts of the firefighters, Boston's commercial district, stretching from Washington Street to Boston Harbor and between Summer and Milk Streets, ended up being completely destroyed by the fire.

Exploding gas lines

The damage done by the Great Boston Fire was also accelerated by the effect of gas lines used for lighting buildings. Because the gas lines were either poorly constructed and maintained or were not shut off quickly enough, the Boston Public Library writes that gas was soon feeding the flames of the fire. And around 3:30 in the morning on November 10, roughly eight and a half hours after the fire started, the flames were reignited from gas explosions in numerous buildings. According to Devastating Disasters, the exploding gas lines were responsible for increasing the heat of the fire until even the granite of the buildings was melting.

Postmaster William L. Burt, one of the people who fought the Great Boston Fire, described seeing huge bodies of gas up to 25 feet in diameter "rise 200 feet in the air and explode, shooting out large lines of flame 50 to 60 feet in every direction, with an explosion that was marked as the explosion of a bomb," per "Brookline, Allston-Brighton and the Renewal of Boston" by Ted Clarke.

Gunpowdering firebreaks

In an attempt to halt the progression of the fire, firefighters decided to blow up buildings to create a firebreak and leave the flames with nothing to burn. According to "The Great Boston Fire," although fire breaks of this sort were a technique that had been used successfully in the past, blowing up buildings carried more risks than it yielded rewards.

Chief Engineer John Damrell was hesitant to blow up buildings using gunpowder, but he ended up giving out several permits for Postmaster William L. Burt and a few other people to destroy buildings to create fire breaks. According to Mass Moments, Damrell ended up agreeing to give out permits due to pressure from both Burt and Mayor William Gaston.

Unfortunately, Schorow writes that Damrell "later considered this action his biggest mistake during the Great Fire." The Report of the Commissioners would go on to agree with him and acknowledged that he was pressured into the decision to use gunpowder but maintained that the use of gunpowder was "objectionable...because it was dangerous and inefficient." The Report would also go on to state that "the greatest wonder of that night was, that no life was lost, and no personal injury was incurred from the use of gunpowder."

Boston's largest fire

In total, around 30 people were killed during the Great Boston Fire, including 11 firefighters, although the exact number of casualties is known. And by the time firefighters managed to put out the fire by midday on November 10, almost 800 commercial buildings had been destroyed. The fire was finally extinguished at State Street during the firefighters' attempt to save the Old State House, Clarke writes in "Brookline, Allston-Brighton and the Renewal of Boston." The Kearsarge Steam Fire Engine that arrived from Portsmouth, New Hampshire is also credited with saving the Old State House.

Covering 65 acres, the Great Boston Fire is the largest fire the city has ever seen and is one of the most costly fire-related incidents in American history. According to the New England History Society, the damage from the fire amounts to over $1 billion in losses today. Comparatively, the Great Chicago Fire resulted in over $3 billion worth of damages today.

With their buildings and materials destroyed, hundreds of businesses were ruined and thousands of people lost their jobs. An unknown number of people also ended up losing their homes. Some insurance companies even went bankrupt from trying to cover the losses from the fire. However, reconstruction began almost immediately and the damaged area was largely rebuilt within a year.

Blaming the Chief Engineer

After the fire, Fire Chief Engineer John Damrell came under fire himself for failing to more effectively subdue the fire. But of all the people in Boston, Damrell tried the hardest even before the fire started to prevent such an incident from ever occurring. The New England Historical Society writes that in 1871, Damrell went to Chicago to see the aftermath of the Great Chicago Fire. There, he realized that the chance of a fire consuming Boston as well was incredibly high.

Upon his return, Damrell tried desperately to increase Boston's fire safety. But Mass Moments writes that although he was able to successfully lobby for the right to do building inspections, there was little he could do about the narrow and crowded streets of Boston. Damrell even had fears about the low water pressure of the old pipes that would be unable to reach the roofs of new buildings, but "the city councilors thought his request to install new water mains was extravagant, and they rebuffed him." Luckily, in response to the equine flu, Damrell hired 500 extra men.

But despite everything that Damrell did before and during the fire, officials held him responsible for the disaster. Damrell ended up resigning in 1874 and the Boston Public Library writes that he went on to found the National Association of Fire Engineers, now known as the International Association of Fire Chiefs, and campaigned for nationwide building safety codes.

History repeats itself

The Great Boston Fire bore many similarities to the Great Chicago Fire, which had devastated the mid-western city just one year earlier. Like Boston, WTTW writes that Chicago also had many wooden buildings that were crowded together on the streets. New York City also saw a Great Fire in 1835 that destroyed 700 buildings, most of which were commercial buildings, which also left thousands of people unemployed. This also wasn't the only Great Fire that Boston saw. The Great Fire of 1787 is considered to be one of the greatest fires in Boston's history, destroying up to 100 buildings in the south of the city. London also saw its own fire during a period of rapid urban growth during the 17th century.

As Schorow notes in "The Great Boston Fire," the real tragedy of the Great Boston Fire is the fact that the disaster could've been avoided. Damrell went to Chicago and knew a year in advance what the city could do to avoid a similar disaster. "All that destruction was a disaster foretold, a tragedy caused not by capricious nature or an unfathomable deity, but by the determined ignorance of men who, like far too many figures in history, supposed nothing would go wrong."

According to "On Capitalism and Inequality" by Robert U. Ayres, both the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and the Great Boston Fire of 1872 also contributed to the Long Depression that followed the Panic of 1873.

Rebuilding the city

After the Great Boston Fire, the city was rebuilt quickly. This was partly due to the insurance money that businesses received as well as private capital. And many buildings, like Trinity Church, were built out of the ashes of the Great Fire. However, many later attempts to rebuild were reportedly frustrated by several smaller fires, according to "Boston Catholics" by Thomas H. O'Connor. The Boston Public Library writes that in the clean-up, most of the rubble was dumped into the harbor to create what is now Atlantic Avenue.

Building codes were also strengthened in the aftermath of the fire. And all the new buildings being rebuilt had to meet these stricter codes. Clay McShane and Joel Tarr write in "The Horse in the City" that new building codes also didn't allow for the construction of new small stables for horses and that new stables had to be less flammable.

However, according to "Brookline, Allston-Brighton and the Renewal of Boston," there was little else done in the way of rebuilding the city to prevent a similar fire and the streets were neither widened nor straightened. This was largely due to resistance by individual property owners as well as municipal agencies. As per Clarke, "Those who owned real estate in the area wanted to protect their own holdings and resisted any grand plans for taking property by eminent domain and planning a new business district for which they would have been taxed as abutters."