Does Women And Children First Still Apply When Boarding Lifeboats?

Humans have been sailing the high seas for tens of thousands of years. During most of that time, sailing has been the domain of men: There have been exceptions, of course, but for thousands of years the open seas were simply not considered a safe place for women or children. That all changed when large-scale oceanic mass transit became a thing, and whole families started booking passage across the high seas.

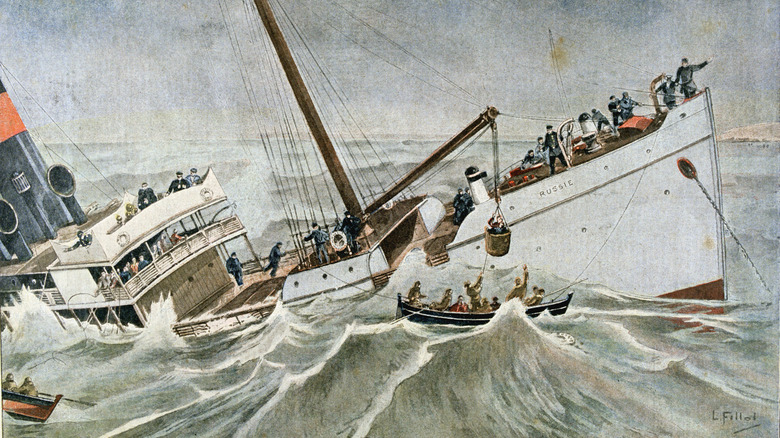

In 1853, according to The Phrase Finder, the HMS Birkenhead sank off the coast of South Africa, with 480 British troops and about 26 women and children aboard. As would be the case for a calamity that would bedevil the Titanic six decades later, there weren't enough lifeboats on the HMS Birkenhead to spirit everyone to safety. The ship's captain ordered the sailors to prioritize women and children for the available lifeboats, and it worked. All of them were saved, while the majority of the sailors drowned or were eaten by sharks.

The "Birkenhead Drill," as it came to be called, set the stage for a code that would govern the high seas for the better part of the next century. Specifically, it also originated both a phrase and code of conduct for disaster protocols: "Women and children first."

The Birkenhead Drill was a moral code, not a law

In 1857, a few years after the Birkenhead disaster, another ship went down while women and children were on board — and in that case, too, were they given priority in boarding the lifeboats. Per a paper on the subject available through Columbia University, William Herndon, the captain of the S.S. Central America, reportedly told his men to "save the women and children," after the ship became caught in a hurricane. The crew understood it meant that they (the men) would likely die; the majority of them did.

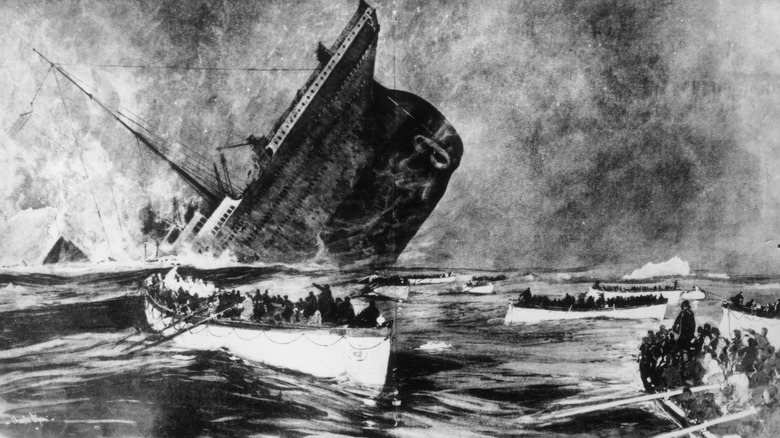

But here's the thing: "Women and children first" was never an actual maritime law, according to another 2006 academic paper published by The Journal of the Social History Society. Rather, the concept was simply a moral code that sailors and passengers lived by. That code was sacrosanct, too. In the case of the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, many of the men who managed to sneak, bully, luck, or jump their way onto a lifeboat were later considered cowards. One tragic example, according to The A.V. Club, was the story of a male Japanese survivor named Masabumi Hosono, who was one of the last two people allowed to board lifeboat 10. Unfortunately, he was later considered a coward by the public at large and eventually died by suicide due to the fallout.

'Women and children first' no longer holds on the high seas

According to The Guardian, most modern sailing vessels — cruise ships, in particular — are designed to mitigate the problems that gave birth to the phrase "women and children first." The reason? Thanks to strict safety measures, ships tend to have enough lifeboats. Specifically, international maritime law requires lifeboat capacity to be at 125% in proportion to the total number of passengers and crew members per ship, according to The Guardian. All passengers on modern cruise ships are pre-assigned a lifeboat. Instead of adhering to "women and children first," priority is first given to passengers with mobility issues for boarding. After that, passengers are then given priority over the crew. The last people to board the boats are the crew members who manage the ship's emergency systems.

Of course, reality can sometimes differ from the ideal. Consider the case of the 2012 sinking of the cruise ship Costa Concordia (pictured above). After the vessel struck a rock formation, panicked passengers attempted to board lifeboats. "It was every man –- and crew member –- for himself," wrote the Daily Mail in 2012, attributing the quote to a number of nameless survivors. No one purportedly made any attempt to prioritize women and children, per the tabloid, and fights broke out on the ship as passengers and crew clamored for space in the lifeboats. In the end, 32 people died, including 27 passengers and five crew members.