15 Things You Might Not Know About The Kentucky Derby

You don't have to be a horse person to appreciate horse racing. What's not to love, besides the part where racehorses die all the time from stuff like broken legs, respiratory injuries, and multiple-organ failure? If you can overlook those minor details, though, there are the fancy hats, mint juleps, and a chance to lose thousands of dollars betting on the last-place horse. Any way you look at it, a day at the races is exciting, even if you're just watching at home on television.

Still, the enduring popularity of horse racing is a little hard to get your head around, especially when you consider that horses aren't really a part of popular culture like they used to be, and sports fans have lots of opportunities to watch much, much faster races (NASCAR, motorcycles, Indy cars, etc.) Maybe it's because horse racing is just so unlike any other sport, or maybe it's just because of the long, quirky, wonderful history of its most famous event: the Kentucky Derby. Here are a few things you might not have known about this century-and-a-half-old American tradition.

The Kentucky Derby founder had a famous grandfather

You probably learned about the rather messed-up expedition of Lewis and Clark as a kid. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark got a bunch of guys together and traveled into the wilderness, where they mostly just made maps and tried to convince the indigenous people that colonialism was totally cool. Seventy years later, Clark's grandson Meriwether Lewis Clark Jr. (you're not transposing words; he was named after his grandfather's travel companion) founded a horse race that people are still watching today.

Clark the younger not only founded the Kentucky Derby in 1875 but also built Churchill Downs — which has a seriously shady side — though neither one of those ideas was especially original. In fact, Clark was basically just copying Epson Downs in England, which was home to a nearly century-old race called the Derby Stakes. Just in case you thought "derby" has always meant "horse race," it hasn't — the Derby Stakes was named for a person: The 12th Earl of Derby, so Clark wasn't even trying to be original when he picked the names "Churchill Downs" and "Kentucky Derby." He also borrowed the length of the race and the rules of entry from the Derby Stakes (1.5 miles, 3-year-old horses). Since the 12th Earl of Derby had died decades earlier, in 1834, he couldn't really be annoyed.

A party caused roses to be adopted as the official flower of the Kentucky Derby

Roses grow just fine in Kentucky, but it's not like they're the official state flower or anything. That honor goes to the goldenrod, though it was previously bluegrass, hence Kentucky's state nickname being the Bluegrass State. According to legend, roses became the official flower of the Kentucky Derby back in 1883, at an after-party thrown by New York socialite E. Berry Wall, also known as "King of the Dudes." It is worth pointing out that, back then, the term "dude" was used to denote a guy who was way too concerned with dressing fancy.

The King of the Dudes liked to throw parties and impress women, and at this particular party he was passing out roses to all the ladies. The Derby's founder, Meriwether Lewis Clark Jr., was impressed by how much all the ladies seemed to like their roses, so he decided to make roses the official flower of the Kentucky Derby. And so, in 1896, the related tradition of draping the winning horse with a blanket of roses was born.

The Kentucky was saved by a resurgence of antebellum culture

The Kentucky Derby plowed on through history until the mid-1890s, when it became clear that the iconic Kentucky racetrack was actually just a money pit. In 1894, the track was bought out by a group of investors who failed to make it profitable, and then resold to another group of investors in 1902. One of those later investors was a successful tailor named Matt Winn.

Winn was largely responsible for defibrillating the nearly bankrupt Derby, and he basically did it by changing the whole vibe of the track and its famous race. Winn launched a publicity campaign designed to appeal to folks who missed the pre-Civil War days, when women wore giant hoop skirts and people pretended enslavement was fine.

There must have been a market for that sort of thing because his campaign worked. Shortly thereafter, the Derby became the strange costume party that it still is today, with everyone wearing ridiculous hats and drinking mint juleps. Who doesn't love to dress up, drink too much alcohol, and bet on the losing horse? It's a pretty simple formula.

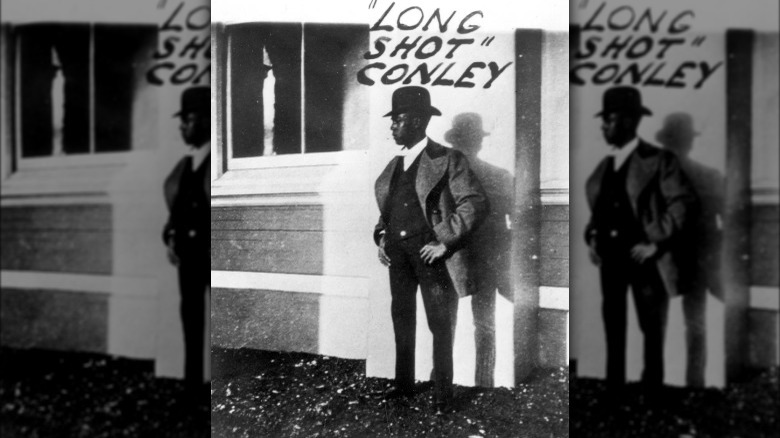

The Kentucky Derby was once dominated by Black jockeys

There were 15 horses and 15 jockeys in the first Kentucky Derby, and 13 of those jockeys were Black. In fact, Black jockeys dominated the sport until 1902, when jockey Jimmy Winkfield rode the winning horse, Alan-a-Dale, across the finish line. Indeed, in the 1880s, racetracks were pretty integrated places. By the 1890s, though, racism was turning the Derby into a hostile place, and Black riders were starting to feel a lot less welcome. The next-to-last Black jockey to enter the Derby before 2000 (the last was Henry King in 1921) was Jess Conley (pictured above) in 1911, who placed third on Colston, the owner of which was also Black.

There isn't really any official record of what ultimately led to the disappearance of Black jockeys, but according to NBER, a reporter for The New York Times recounted gossip that white jockeys had "organized to draw the color line," which basically means they asked horse owners and other influential people to shut Black riders out of the sport. The reporter even implied there was something of a conspiracy to sabotage Black riders. "Somehow or other," he wrote, "they met with all sorts of accidents and interference in their races. The doubting horse owners seem to have been convinced ... that if they want to win races they must ride the white jockeys."

The longest long-shot winner in Derby history had 91-1 odds

Oddsmakers have a sort of formula that helps them decide which horses have the best chance of winning, but it's not as simple as just plugging some info into a computer. Oddsmaking also depends on the subjective analysis of human beings. People who watch horses in training, study racing forms, and are just general racing experts all have some input, and the odds also include variables like a horse's perceived ability, who the oddsmakers think the public might favor, how each horse runs, and what everyone thinks a horse's chances of winning will be.

Even with all those subjective variables, oddsmaking is much more of a science now than it used to be. Still, oddsmakers often get it wrong. In 2022, Rich Strike was given 80-1 odds, yet still won the Kentucky Derby. Entered into the race at short notice after another horse was unable to run, Rich Strike had only competed in seven races. To a shocked crowd and perhaps an even more shocked trainer, the horse came from behind before thundering through the leading pack, winning the race in just over two minutes.

But even those odds don't match those of Donerail, which began the 1913 Derby with 91-1 odds, and won. As of 2024, Donerail (pictured) still holds the record of the longest long shot to ever win the Kentucky Derby.

The Kentucky Derby is shorter than it used to be

For the first 21 years of the Kentucky Derby's existence, the race was a grueling 1.5 miles. Today, only the Belmont Stakes is that long, and as the final leg of the Triple Crown, it's the longest race that any thoroughbred racehorse is likely to run in its career.

In 1896, it finally dawned on someone that maybe 1.5 miles was too much to ask of thoroughbreds that were barely past their third birthdays, so the distance was dialed back to 1.25 miles, which is the length it remains today. That change in distance is evident if you look back at the winning times across the race's history — before 1896, winning times rarely surpassed 2 minutes 37 seconds. Today, winners usually finish the race in an average of just over 2 minutes, a number that has stubbornly stayed much the same for many decades.

American horses rule, at least most of the time

Over the long history of the Kentucky Derby, most of the horses that won were bred in the state of Kentucky. That's not super-surprising, since horse breeding and racing are both a big thing in Kentucky, so it's really a numbers game more than anything. As of the 2024 Derby, 116 out of 149 Derby winners have been Kentucky-born.

Occasionally, horses that aren't Kentucky-bred do win the Derby, but those numbers lag way, way behind the Bluegrass State. Florida, for example, has contributed six winners, and California and Virginia have each contributed four. It's even less common for horses born outside of the United States to win the Derby. In 1917, British-born Omar Khayyam won the Derby, but a non-U.S. native didn't win again until 1959, when British-born Tomy Lee finished first. Two Canadian horses (Northern Dancer in 1964 and Sunny's Halo in 1983) also broke the nationality barrier, but none since.

To be fair, Kentucky-bred horses might have a teensy advantage. The Kentucky Horse Racing Commission provides millions of dollars in incentives to Kentucky-bred horses that go on to win races. In 2024 alone, the program made $20 million available to Bluegrass State breeders, and only Bluegrass State breeders.

The slowest Derby winner was really, really slow

Everyone knows Secretariat has the fastest derby record. At 1 minute 59.40 seconds, no other horse has really come close to beating the legendary thoroughbred. But who has the slowest win? Naturally, history remembers that, too, even though everyone who was associated with the embarrassingly slow Stone Street is long gone.

In 1908, Stone Street (pictured) finished the race at 2 minutes 15.20 seconds, a whopping 16 seconds slower than Secretariat. As of 2024, he still holds the record as the slowest Derby winner of all time, at least since 1896, when the race was first shortened to 1.25 miles. To be fair, the track was muddy and horses don't always run that well in those conditions, so there was at least a reason for the very slow win.

If you want to count the horses that ran the race when it was still 1.5 miles, the honor of slowest-ever winner goes to Kingman, who in 1891 finished at 2 minutes 52.25 seconds. All four jockeys in that year's running had been told to keep it slow for the first mile, which made the whole race artificially sluggish.

Only three fillies have ever won the race

Stallions, geldings, and mares compete on pretty even footing in many equestrian sports. Gender doesn't matter that much for things like dressage, show jumping, and rodeo; winning in these sports is more about good training and good horsemanship than it is about gender. But in tests of pure speed, female horses aren't usually thought of as being competitive with male horses.

In the century and a half that the Kentucky Derby has been a thing, only three fillies have placed first: Regret in 1915 (pictured), Genuine Risk in 1980, and Winning Colors in 1988. As of 2024, that's out of 40 filly competitors total (compared to a couple thousand or so colts), so the odds are stacked against them before they even leave the starting gate. Even so, it's not necessarily just gender bias that makes the pool so heavily favored towards colts.

Trainer John Shirreffs told the LA Times that colts are better racing prospects partly because they like to "roughhouse," and American horse racing is a sport that includes a lot of jostling around on the track. This is different from horse racing in Europe, where fillies tend to be more competitive. Fillies also have a size disadvantage, so those that are competitive against colts are often larger than average.

Gray horses almost never win

Gray horses almost never win the Kentucky Derby, either. The reasons for this are a lot less mysterious, though. It's not because gray horses are somehow fundamentally less fast than bays and chestnuts, it's just because there aren't as many of them.

In the most recent 111 Kentucky Derbies up until 2024, there were eight gray winners; only 7% of other coats. The reason for this is simple: gray thoroughbreds are rare. Chestnuts, on the other hand, made up about 20% of the registered thoroughbreds, and bays pretty much make up the remaining majority. Therefore more bays and chestnuts win simply because there are more bays and chestnuts.

So if you want to look at it based on numbers, bays have been underperforming at the Kentucky Derby, chestnuts have been overperforming, and grays have done more than twice as well as might be expected. So the moral of the story is, don't bet against the gray horse because it's gray. Just like human beings, color has nothing to do with ability.

Only 12 Derby winners have gone on to sire other winners

It's tempting to assume that greatness always begets greatness, especially since we are used to seeing the sons and daughters of talented people go on to demonstrate similar talents in similar careers. But with horses, it's not really that simple. Owning a horse that was sired by a Kentucky Derby winner is not a sure bet that one day that horse will also be a Kentucky Derby winner.

Lots of different things go into making a horse great, and it's not just genetics — training, the skill of the horse's jockey, and frankly, how much money you've got to put into all of that are all just as important as who the horse's sire is. Just to prove this point, in the 150-year history of the Kentucky Derby (up until 2024), only 12 Kentucky Derby winners have gone on to sire Kentucky Derby winners.

Even the great Secretariat, throughout his entire crazy real-life story, didn't produce any notable sons or daughters: not one of his 600 foals had an especially impressive racing career (though he did have a great-granddaughter who won the Belmont Stakes). That alone should be enough to prove that "like father, like son" doesn't really apply to thoroughbreds.

Female jockeys are way, way underrepresented

Just as female horses are underrepresented in the Kentucky Derby, so are female jockeys. That's actually more surprising than the absence of fillies on the race track, since women have a lot of natural qualities that make them exceedingly well-suited to be jockeys. For example, jockeys tend to be small, and there are many more small women than small men. Women also tend to be more drawn to horses than men: American horse owners and managers are overwhelmingly women. Women are excellent riders and proven athletes, and there's absolutely no reason why they should not be better represented at horse races like the Kentucky Derby. And yet, they aren't.

The first woman to ride in the Kentucky Derby was Diane Crump in 1969, and male jockeys were about as happy about her participation as you might imagine male jockeys would have been back in 1969. None of their predictions about her general fitness to compete turned out to be true of course, but since then, the numbers have remained abysmal, as only six other women have ridden in the Derby. Unlike with fillies, though, this isn't about capability, it's about numbers (once again). Women can ride as well as men, it's just that there aren't as many opportunities for them to participate. If the field were more 50-50, it's unlikely the Kentucky Derby's winner's circle would be so male-dominated.

The Derby has never been canceled because of weather

If you've ever been to Kentucky, you know the weather is pretty okay. Summer temperatures range in the high 80s, and winter temperatures drop down to the 20s. That makes the Bluegrass State a good place to have a horse race, especially since average temperatures in May are usually in the mid-70s. Mother Nature doesn't pay a whole lot of attention to averages, though. The temperatures on Derby day have ranged from a high of 94 degrees to a low of 36.

Temperature alone isn't usually enough to red- or green-light a sporting event like the Kentucky Derby, but you might imagine rain would be. And yet, the Kentucky Derby has never been canceled because of rain (or for any other reason), even though there have been some ridiculously rainy race days and/or race days where previous days' rain left the track muddy and difficult for the horses to run on.

Stone Street's infamously slow 1891 race was a run on a muddy track, and around 3.15 inches of rain came down during the 2018 running, making it the wettest race on record. Still, the race went on despite the torrential downpour, which probably ruined more than a few fancy hats and the chances of more than a few horses unaccustomed to running in those conditions. Justify (pictured) won that wettest of all Derby races in 2018, with a so-so time of 2 minutes 4.20 seconds.

Post 1 is unlucky, and post 5 is the luckiest

Most athletes are at least a little superstitious, and a few athletes are weirdly superstitious. Horse racing, for whatever reason, seems to be one of the more superstitious sports. The color green, for example, is largely thought of as unlucky in racing circles.

Some racing superstitions have at least a little basis in fact, though. Post number 1, for example, is one of the most unlucky posts, but that's at least partly because a horse that breaks from that position tends to get crowded on the inside of the track. Posts 2, 9, 12, 14, and 17, however, are even less lucky (the last time a horse won from post 14, for example, was in 1961). That's a little harder to explain.

Post 5, on the other hand, is one of the luckiest. Ten horses breaking from post 5 have gone on to win the Derby. It's not clear why, though it's probably a safe bet that it has at least something to do with the fact that there haven't been enough Derbies to provide a decent statistical picture of the winningness of each particular gate.

Churchill Downs sells 120,000 mint juleps every year

The mint julep — a sugary whisky cocktail with a distinctive mint garnish — is one of the Kentucky Derby's most iconic and enduring traditions, introduced by Matt J. Winn in the early 1900s as part of his Southern revival of the race. But how many mint juleps does Churchill Downs sell each year? The answer is a lot: around 120,000.

While that sounds like an awful lot of whisky and mint being quaffed, per person it's probably less than one. On average, around 150,000 people attend the Kentucky Derby each year, and at least some of those people are likely to be under the age of 21, so it's likely a very rough average of one per legal drinker. That means most people who watch the Kentucky Derby are at least one cocktail from sober, and that is just as well because when you bet on the losing horse, you need all the extra help you can get.