The Untold Truth Of The Cossacks

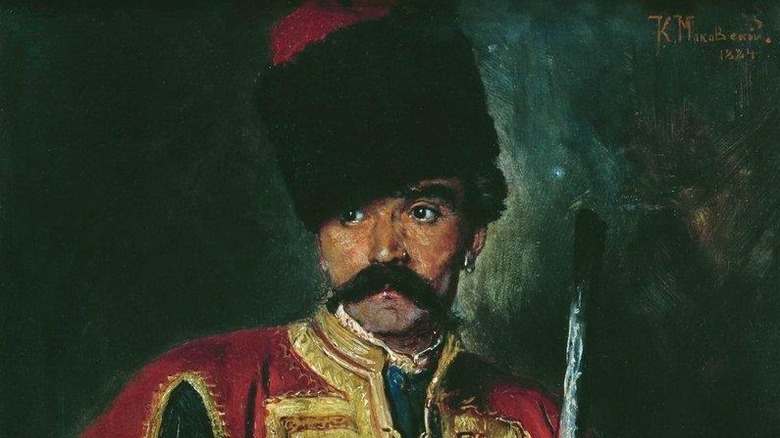

In the 15th century, the vast steppe between the Crimean Tatar Khanate, Poland-Lithuania, and the Russians of Muscovy was a dangerous region to live in. Though a scorching hot melting pot was formed within that volatile environment, which then forged a formidable group of warriors to dominate the frontier land called Ukraina, or "on the border." These fiercely independent, martial people are known as Cossacks, from the Turkic word kazak, meaning "free man" or "adventurer."

The Cossacks risked a life in no man's land because they refused to merely survive in a form of slavery as peasants under the rule of the nearby kingdoms. At first, they just lived off the land through hunting, fishing, and foraging honey. But eventually these rugged individuals banded together to become an impressive fighting force.

Once unified, the Cossacks preserved their independence and successfully protected the region from invasions. After the Russians began to realize how effective these warriors were against Tatar assaults, they recruited large numbers of the Cossacks into their armies and expanded Russian territory. To show their appreciation, the czars sought to control the unruly horsemen, leading to several rebellions, but the autonomy of the Ukrainian-based Zaporozhian Cossacks was dealt a major blow when a treaty was signed with Russia in the mid-17th century to gain protection from Poland-Lithuania. Ever since, Moscow has used this agreement to claim dominion over Ukraine, and as time passed, the right of the Cossacks to rule themselves was whittled away entirely.

The early Cossacks were not just one ethnicity

Even though the Cossacks thrived in lands now within the borders of modern-day Ukraine and southern Russia, they were not comprised of one single ethnic group. The majority were Slavic Christians, but there were also significant numbers of Poles, Moldovans, Greeks, Jews, and Muslim Tartars among them as well, according to Paul Kubicek in his book, "The History of Ukraine." In fact, the very first Cossacks were made up almost entirely of Tatars until the influx of peasants from Poland, Lithuania, and Russia made Slavs the larger group.

For those who wanted to join the Cossacks, where they came from did not matter, but there were other crucial requirements. Not only did wannabe Cossacks have to endure seven years of strenuous combat training, but they also then had to use those skills to protect their new brothers and be willing to defend the Orthodox Christian Church, even from neighboring Catholic Poles. Officially, the warriors were not allowed to marry either, but there were those who bypassed this rule by having families in villages outside of their Cossack military forts.

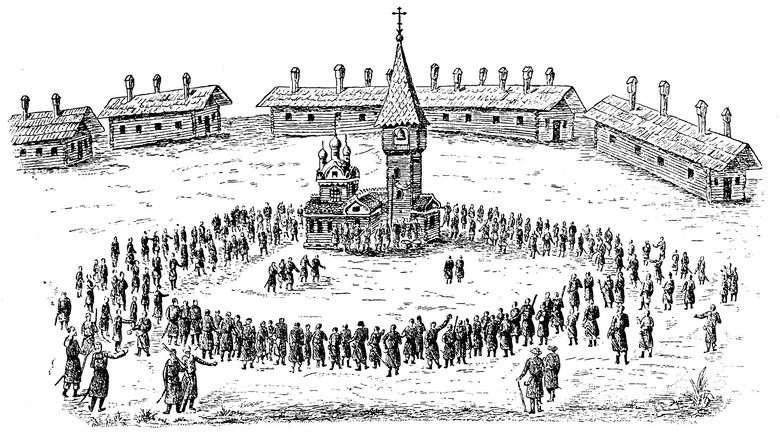

Military forts known as sichs were their homes

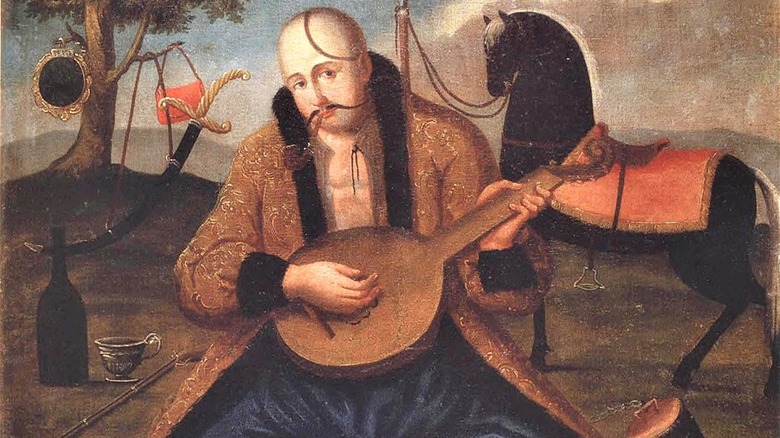

To protect themselves from the raiding forces of the enemies that surrounded them, the early Cossacks constructed multiple fortified camps called sichs to live within. These highly organized settlements were much more than just walls around their homes, as the sichs also contained administrative buildings and schools to make sure every Cossack was literate, says TED-Ed. While they worked to provide for themselves and trained for war throughout the day, the Cossacks were then able to feast, play music, and dance at night behind the safety of their walls.

By the 1550s, the largest and most powerful of the military forts was the Zaporozhian Sich, located on the island in the Dnieper River known as Zaporizhzhia, or "beyond the rapids." This sich and the other Cossack settlements brought order and community to a land that had been ravaged by warlords and bandits for years.

Sichs had rare democratic governments, but only for men

Since freedom was often their main desire, the Cossacks established a rare type of democratic government within their sichs that was certainly the first of its kind both in Ukraine and the surrounding lands. Decisions were made through a general assembly called a rada where their leader and other officials were all elected to office, according to Britannica. No one inherited power, regardless of their background, including former chiefs known as hetmans.

It is important to note, however, that no matter how unique or sophisticated these proto republics were, they were not technically states in the modern sense because they lacked several key features, such as written laws and defined borders, and a common currency. Plus, the head of the government and the army were one in the same, and that lack of division is a characteristic far more common among premodern institutions (via "The History of Ukraine"). The sichs also may have been free for the men who lived there, but not for any women since they were not even allowed to enter the Zaporozhian Sich.

Punishments were brutal to prevent lawlessness

One Cossack tradition was to always leave the doors to their huts open so that friends, travelers, or anyone else could seek shelter or a place to cook whenever they needed it, even if the homeowner wasn't there. Another rather communal custom was that if someone found something that did not belong to them, they must tie the item to a pillar and leave it there for three days. If the original owner did not claim it, the item belonged to the person who found it.

Yet while these customs were generous, there were limits. Thieves were not allowed to take anything from the homes they stayed in, and if they were caught with possessions that did not belong to them and had not been strapped to a pillar, there were certainly repercussions. There were no police or prisons in Cossack communities to prevent crimes because the punishments were so brutal if caught that it deterred most. According to Ukraine World, both theft and murder resulted in execution. Criminals were either buried alive with the one they killed, or savagely beaten to death.

Alcohol was banned on campaign, yet heavy drinking persisted

To prevent intoxication at times when alertness was pivotal to survival, alcohol was outlawed on military campaigns. And if this law was broken, the punishment was death. The penalty was most likely so severe because in times of peace many Cossacks may have drunk to excess, and that's putting it mildly based on at least one contemporary account.

"The History of Ukraine" says that several sources commented on both the violent aggression of the Cossacks and their heavy drinking. An envoy from Venice in the 17th century once said, "This Republic [the Cossack Sich] could be compared to the Spartan, if the Cossacks respected sobriety as highly as did the Spartans." But as Destinations points out, the men couldn't have gotten intoxicated all the time because there simply was too much work to do in maintaining both the sichs and their individual households.

Sichs had pagan magicians called Kharakternyks

The Orthodox Christian faith was a huge part of the Cossack identity. However, that did not mean that all aspects of their Slavic pagan beliefs were eliminated from their culture. One remnant from the ancient past still within these communities was the presence of magicians in the sichs known as Kharakternyks. Among the various mythical abilities they supposedly had were the powers to catch bullets, transform into animals, and breathe under water.

Legends stated that the sorcerers were the descendants of pagan priests who were once highly respected in Russian society until Prince Vladimir the Great adopted Christianity for the Kievan Rus in 988. Having lost their prominent status, the pagan magicians went to the steppe where they used their extensive knowledge and abilities in the service of tribal warlords. In reality, it is far more likely that the Kharakternyks had a more recent history as a part of the many wandering diviners, artists, circus performers, and magicians throughout eastern Slavic lands who joined the Cossacks and established themselves in their communities.

Along with performing magic rituals, the Kharakternyks had very practical responsibilities as healers and, essentially, as therapists for the warriors who fought frequent battles. To this day, pagan beliefs have survived as sacred rituals in honor of nature, and they are still carried out on Zaporizhzhia Island, according to BBC News.

Modern martial artists are restoring a Cossack combat style called Hopak

As a warlike people who constantly trained for battle, it makes perfect sense that the Cossacks had their own fighting style, known as Hopak. Using expert dance-like skills to improve their combat techniques, the Cossack art is exceptional with its movements that shift rapidly from crouching positions to acrobatics, says Fightland. Combat hopak also utilizes punches, kicks, throws, and grappling as well.

Unfortunately, much of what was once known about the Cossack martial art was lost after centuries of cultural repression under the domination of the Russians. On the other hand, the Cossacks cleverly hid their combat moves in the more acceptable dance version of Hopak, so martial arts experts have had much success reviving the old martial art since the mid-1980s. For a people struggling to preserve their identity, the resurrection of Hopak has been a major cultural victory for the Ukrainians who see themselves as the descendants of the Cossack warriors.

Early Cossacks also fought for Poland

The Cossacks are often known as independent warriors fighting for their liberty, or as a formidable part of the Russian army. But even though the lethal horsemen allied with Moscow, they also fought against it as part of the Polish forces in the early 17th century. The Cossacks were a key part to Poland's victory over the Turks at the Battle of Khotyn in 1621.

Yet, just as the Russians did years later, the Poles refused to accept the Cossacks merely as allies and made several unsuccessful attempts to subjugate them. In the words of a contemporary Polish aristocrat, "The Cossacks are the fingernails of our body politic. They tend to grow too long and need frequent clipping" (via "The History of Ukraine").

During their last and greatest revolt against Poland, the Cossacks had much success but were still unable to overcome the forces of their more powerful enemy. In desperation, the legendary hetman of the war, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, turned to the Russians for support, which ended up being a massive mistake. In January 1654, Khmelnytsky pledged his obedience and from then on, the czars had claimed to be the rulers of both Russia and Ukraine.

Napoleon was impressed by the Cossacks' fighting skills

In 1812, Napoleon Bonaparte was at the height of his power as he ruled over the French Empire that dominated much of Europe. From this impressive position, the general made the disastrous decision to invade Russia with a gargantuan army that reached as high as 612,000 men.

According to Stephen Summerfield in "Cossack Hurrah! Russian Irregular Cavalry Organization and Uniforms During the Napoleonic War," the Imperial Russian Army that opposed the invaders included 107 Cossack horse regiments and 2 and a half Cossack artillery companies. Overall, most accounts of the conflict spoke of the Cossacks in admiration of their fighting skills, but their level of discipline and organization was no match against experienced infantry in formation.

Of all the military commanders that witnessed the Cossacks on the battlefield though, the one who may have respected them the most was the head of the French forces. Napoleon said, via TED-Ed, "Cossacks are the best light troops among all that exist. If I had them in my army, I would go through all the world with them."

More than one massacre was committed by the Cossacks

The massive rebellion against Poland was an extremely stressful time for the Cossacks as they struggled to remain free of foreign occupation. And in a horrific fashion much too common throughout history, the Cossacks took their frustrations out on a scapegoat population: the many Jewish communities throughout the region.

One contemporary account about the Cossack attacks of 1648 said, "Wherever they found the szlachta, royal officials, or Jews, they killed them all, sparing neither women nor children. They pillaged the estates of the Jews and nobles, burned churches and killed their priests, leaving nothing whole. It was a rare individual in those days who had not soaked his hands in blood" (via "The History of Ukraine"). Estimates of the dead vary during this massacre, and it is unlikely that the death toll exceeded 50% of the total population, but even that number is staggering at 20,000 people.

After the Cossacks were fully integrated into the Russian army, the soldiers were ordered to carry out several more massacres during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including a particularly brutal one in 1919. During the Ukrainian Civil War following the Russian Revolution, Jewish populations were once again blamed for the resulting chaos even though they had little to do with it. Thousands of innocent people were murdered across the region over the next few years, but the worst of these occurred at Proskurov where 1,500 Jews were killed within the span of only a few hours.

The Bolsheviks carried out Decossackization

The Cossacks may have served as cruel butchers for the Russian Empire on too many occasions, but once the Russian Revolution ended, it was their turn to face terrible persecution after a very brief window of independence. According to Nigel Thomas in his book, "Hitler's Russian & Cossack Allies 1941–45," more of the warriors fought for the White Armies (the side that lost), so many Cossacks were viciously punished without mercy. The Bolsheviks instituted a policy called Decossackization that led to the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Cossacks.

The process was the most devastating tragedy the Cossacks ever faced as the Soviets nearly wiped them out completely. Beginning in January 1919, 10,000 Cossacks were killed, followed by many more afterwards. For evidence of how harsh the persecution was, there used to be 1 million Cossacks before the civil war, and now a significantly smaller number of their descendants live today.

The warriors fought for both sides in World War II

Many Cossacks did not forget the cruelty their people faced from the Russians in the years following the civil war, so it was not surprising that they fought for both sides during World War II. The warriors that remained loyal to the Soviets formed 17 cavalry corps from the Don, Kuban, and Terek Cossacks; however, there were numerous men who fought for the Germans. In fact, when the Nazi forces arrived in the territories of the Cossacks in 1942, they were often seen as liberators from the oppressive Russian government.

When the commander of a Cossack infantry unit, Major Ivan Nikitich Kononov, surrendered, he said to his men, "Those who wish to go with me take up their position on the right, and those who wish to stay take up position on the left. I promise no harm will come to those who wish to stay" (via Warfare History Network). Afterwards, not a single man stood on the left.

After the conflict, the Cossacks who fought for the Nazis were handed over to the Soviet Union and faced years in the gulag as punishment. Others managed to avoid years of torture, but instead were executed almost immediately through a firing squad.

Modern Russian Cossacks fiercely support the Putin regime

After decades of persecution, suppression, and exile, the Russian government under the leadership of President Vladimir Putin drastically changed the way it treated the Russian Cossacks, making them fiercely supportive of the new regime. At first, they served as a type of auxiliary police in a few cities throughout the country and were much appreciated by conservatives and nationalists.

Staff captain Vadim Stadnikov, head of security for the Terek Cossack Army, described how the Cossacks acted differently than normal law enforcement. He said, "There is a prophylactic effect, a kind of education. They come here. Take this group of young people. Explain to them the traditions of the Orthodox, Slavic, Cossack people of the city of Stavropol. What our rules are. How we live here" (via The New York Times). In 2014, their attacks against those deemed immoral received much more publicity when the Cossacks went after the punk group Pussy Riot and the Ukrainian boy band called Kazaky.

Far more dangerous is the Cossack involvement in the current Ukrainian War where the soldiers have served as a paramilitary force. Not only were the Cossacks some of the first to assist Russia in seizing Crimea, but they also formed units that captured entire cities in eastern Ukraine.