How The LGBTQ+ Community Reclaimed The Pink Triangle From The Nazis

If there's one thing that the Nazis did really well, it was to harness the power of symbols — starting with the rebranding of the swastika. In addition to the public propaganda, there were also the symbols used in the concentration camps.

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the symbols sewn onto the uniforms of prisoners were mostly universal throughout the system, with slight variations. In some camps, for example, Roma prisoners were grouped in with "nonconformists" and forced to wear black triangles, while in others, they were their own separate category and identified by brown triangles. The yellow Star of David is perhaps the most famous, but there were variations on that, too. A prisoner who was both Jewish and gay, for example, would have two triangles: the bottom one would be yellow and the top would be pink, forming a two-colored Star of David.

And that's what brings us to the pink triangle. While many of the symbols the Nazis used are no longer acceptable to use in polite company (and in some cases, downright illegal), the pink triangle has moved into the mainstream. It's seen all over as a symbol of solidarity among the LGBTQ+ community, and at a glance, that may seem surprising. Take a closer look, though, and it's a story of resistance, strength, and a promise that what happened in Nazi Germany isn't going to happen again.

The Nazis persecution of gay men started in 1933

The story of the pink triangle has to go all the way back to the beginning, and that's 1933. Before the rise of the Nazi party, Germany was almost shockingly open: According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the pre-Nazi Weimar Republic was an environment where challenges to gender norms were front and center, with thriving gay communities in cities like Berlin, Frankfurt, and Cologne. Gay bars, newspapers, and journals were wildly successful, and there were even "friendship leagues" organized as a support system for the gay community.

There were, of course, still right-wing opponents of the culture that had developed under the Weimar Republic, and the most vocal among them was Adolf Hitler and his cronies. During their rise to power, their views on homosexuality were kept mostly on the down-low, but once they secured their foothold at the top, all bets were off.

One of the first orders given by the Nazi regime was to shut down gay bars and newspapers in cities across Germany (including the El Dorado, pictured). The gay community that had been thriving suddenly found police surveillance lurking around every corner. Books and journals written by gay authors were burned, and by late 1933, gay men were being arrested and jailed. Laws for the arrest and detainment of gay men were added to Germany criminal codes with the infamous Paragraph 175, and, from there, things only got worse.

Nazi persecution of gay men escalated throughout the 1930s

In order to truly understand the baggage and weight of the pink triangle, it's important to talk about just how far the Nazis went in their persecution of gay men. (According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, women were also persecuted, although there were no formal laws on the books prohibiting lesbian relationships.)

Way back in 1931, one of Germany's many left-wing newspapers published a story about Ernst Röhm (pictured), the head of the Sturmabteilung (SA, or Stormtroopers). Röhm, they revealed, was gay.

According to the USHMM, other high-ranking members of the Nazi party already knew he was gay. At first, it was just sort of something that wasn't talked about, and Röhm firmly believed what was going on around him was more about mainstream beliefs than gay rights. Plus, he'd been friends with Hitler for a long time, so that had to count for something ... right?

Fast forward to June 30, 1934 and the kick-off of the so-called Night of the Long Knives. Even though Röhm's Stormtroopers had been the goons lurking in the shadows, guiding Hitler's rise to power, there was a growing worry that the 3 million-strong organization had gotten too big. Hitler and his cohorts laid the groundwork for the Heinrich Himmler-led SS to quite literally chop the head off the SA. Röhm was among those murdered, and one of the reasons given? That he was gay, and therefore, he was a problem.

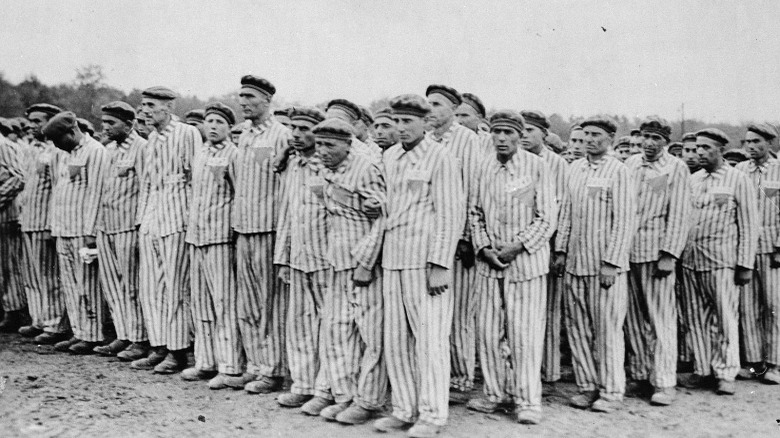

This is what the pink triangle meant for those in concentration camps

In 1935, the Nazis rewrote Paragraph 175. Now, sexual relations between two men was on the books as being a criminal offense, punishable by up to 10 years of hard labor, and was it enforced? Of course it was — partially thanks to Heinrich Himmler and his newly formed (in 1936) Reich Central Office for the Combating of Homosexuality and Abortion.

The United State Holocaust Memorial Museum says that it wasn't long before German agencies like the Gestapo were ordered to do whatever it was they needed to do to find, arrest, and detain anyone even suspected of being gay. Sometimes there was a trial, sometimes there wasn't, and sometimes, they were sent straight to a concentration camp.

It was there that those arrested under Paragraph 175 were identified with a pink triangle sewn onto their uniforms, and according to those who survived the camps, it was a sign that the worst was yet to come. Not only were pink triangle prisoners ostracized by other prisoners (who feared repercussions for associating with them), but they were subjected to some of the worst abuses within the system. In addition to regular physical and sexual abuse, they were targeted for things like medical experimentation in Buchenwald, and forced castration at the will of camp commanders. Liberation came in 1945, but for the survivors, it still wasn't over.

Some prisoners liberated from the Nazis were simply arrested again

After the fall of the Nazi regime and the liberation of hundreds of thousands of people from concentration camps, the ultimate fate of those with a pink triangle was very different from others. Scores of laws that the Nazis had put in place were struck from the record and rewritten ... except for Paragraph 175. That, says the United State Holocaust Memorial Museum, remained, and being gay remained a crime.

That led to a few things happening. Even under Allied occupation, some pink triangle prisoners were imprisoned again to serve out the terms of the sentences that the Nazi authorities had imposed on them. That pink triangle became a post-war burden as well.

Spiegel says that it was only in 1968 that the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) reversed the Nazi-era Paragraph 175, but the stigma remained — and the gay community largely remained ostracized and, in many cases, under surveillance by the Stasi.

Seeds of mistrust planted by the Nazis continued to grow, and even after being gay was decriminalized, a deep-rooted homophobia remained in many areas. It was, after all, a high-profile hate: When Gunter Liftin became the first East German to be shot trying to cross the Berlin Wall in 1961, the government's official line was that he had been gay and fleeing from persecution for "criminal acts." By the next decade, the Stasi's monitoring of the gay community was in full swing, under an operation code-named Orion.

The Nazis' gay victims were forgotten and overlooked for years

In the decades following World War II, the German government has paid reparations to many who suffered unspeakable horrors under the Nazi regime. For a long time, there was one notable exception: pink triangles.

According to the Memorial and Museum at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the rationale was pretty horrifying, with the general consensus being that those people "had no one but themselves to blame."

Can it get worse? Talk about the Nazis can always get worse. After prisoners branded with a pink triangle were liberated from the concentration camps and — in some cases — finished serving their extended sentences, many were unable to return to the homes and the families they'd been torn from. The stigma of the pink triangle and what it represented was so great, that many felt they had no choice but to change everything they could about who they were, in the hope of being allowed to live as close to a normal life as they could, while bearing the scars of what happened to them.

It wasn't until 2017 that Germany overturned the convictions of the tens of thousands of men who were sent to concentration camps, another 50,000 who were persecuted between 1949 and 1969, and the 14,000 who were convicted before the law's full repeal in 1994. The 5,000-odd survivors were awarded damages of around $3,350, plus around $1,700 for each year of jail time (via the BBC).

One man's memoir put the spotlight on the pink triangle

There are scores of World War II memoirs, but, according to The National WWII Museum, one of the only firsthand accounts from a gay perspective is 1972's "The Men with the Pink Triangle," a book written by Josef Kohout under the pseudonym Heinz Heger.

According to The New York Times, Kohout was condemned by a single photograph. On it, he had written of his eternal love for another man, and it was all the Gestapo needed to send the then 24-year-old to Flossenburg. He spent six years in the system, and was among those liberated at the end of the war. Post-war, he lived in Vienna, and on his death in 1994, some of his belongings were given to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. That included a single piece of cloth, bearing the number 1896, and a pink triangle.

That pink triangle is the only surviving badge that can be definitively linked to the man who wore it, and it kicked off a campaign to try to find survivors.

Kohout's account of what he faced as a pink triangle prisoner is credited with opening a dialogue that included more documentation and publication of exactly what that pink triangle meant to so many. Still, many didn't come forward from the shadows they'd been forced into for so long: In 1995, only 15 were known, with eight signing a declaration that read: "The world we hoped for did not transpire."

The symbol was reclaimed by a German gay rights organization

Fortunately, for as long as there has been persecution and hatred, there have been groups fighting precisely that. The Homosexuelle Aktion Westerberlin (HAW) was the first of Germany's widely influential gay rights groups, and they were founded in 1971. At the core of their beliefs was the idea that everyone should have the right to perform consensual acts in the privacy of their own home, and when they were looking for a symbol for the group, nothing seemed right.

Until, that is, the release of "The Men with the Pink Triangle." According to the group's official statement (via Nursing Clio), they saw it as the perfect symbol because it not only focused on the oppression and persecution that plagued the community in the present day, but also "represented a piece of our German history that still needed to be dealt with."

HAW adopted the pink triangle as their symbol in October of 1973, and the idea of tying the injustices of the past to those of the present was pretty genius. Other groups thought so, too, and the use of the pink triangle spread across Germany, with one new group even taking it as their name — Pink Triangle Wuppertal.

The persecution of gay men in Nazi Germany started to become more widely talked about

In 1977, sociologist Rudiger Lautmann came up with a horrifying figure: According to his estimates, around 60% of the men sent to Nazi concentration camps with a pink triangle died there.

That's shocking, and things are about to get even more surprising. According to TIME, 1977 was also the year that they printed a reference to pink triangles being used in the gay rights movement. They were talking about gay activists in Miami who were trying to raise awareness around housing discrimination. They wrote that the pink triangles were "'reminiscent' of Nazi-era yellow stars." It took a reader to write in and explain that no, it wasn't "reminiscent" of anything, it was exactly that.

The reader further explained the current use of the pink triangle: "Gay people wear the pink triangle today as a reminder of the past and a pledge that history will not repeat itself."

It was that group of activists who helped spread the use of the pink triangle into the popular imagery of the gay rights movement in the U.S., and there's a footnote here. It's kind of a given that Allied countries can take the high road regarding World War II, but according to the Memorial and Museum at Auschwitz-Birkenau, American and British attorneys were among the proponents of sending pink triangle prisoners back to jail, to finish the sentences started in concentration camps.

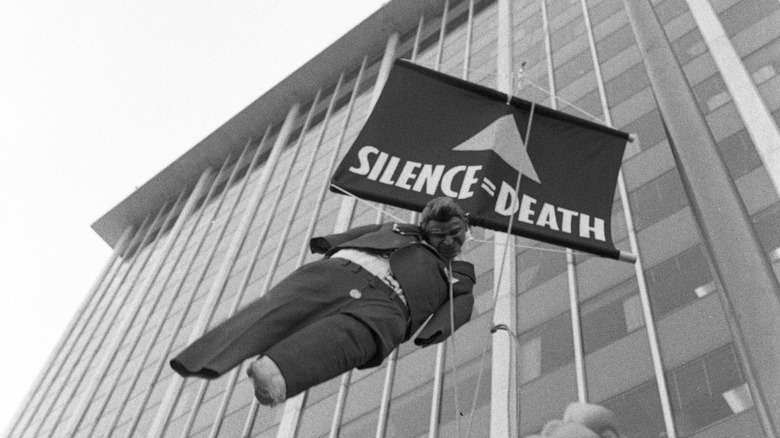

The pink triangle was rotated and used with AIDS awareness

According to Nursing Clio, the use of the pink triangle to symbolize the gay rights movement spread pretty quickly. Less than a year after it became the symbol of Germany's HAW, it was in use in major U.S. cities, and by the 1980s, it was incorporated into the logos of high-profile events like the March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.

Those who wore it never forgot why they wore it, or those who died with it sewn onto their clothing. In one letter penned by the organizers of the 1987 march, they wrote, "Dear friends, we are not going back into the closet. We are not going to be herded into any concentration camps. We are not giving back the hard-won rights we have fought for. And we are not going to tolerate the police in our bedrooms. Not now — not ever."

It was about the same time that the pink triangle was used in another logo. In 1986, New York City activists once again drew a line between the government, deaths of gay men, and the Holocaust with the release of a poster that featured the pink triangle — now with the peak facing upwards — and the words "Silence = Death." The incredibly powerful image would be adopted by AIDS activists calling for a universal right to health care, regardless of sexual identity, and the message was clear.

It's been used as a reminder that persecution is still happening

The pink triangle is, in reality, a pretty simple symbol. It's three-sided and a single solid color, but, according to Nursing Clio, it has a unique history that means it's not just a symbol for the struggles of the present, but is also representative of a shared past. The gay community has been marginalized, ostracized, and persecuted for a long, long time, and the pink triangle unites people across the decades.

And it's still very, very relevant. According to TIME, the pink triangle is still being used to call attention to persecution — particularly in areas like Chechnya. The symbol joined flyers with printed pleas — "Stop the death camps" — an idea that seems as though it should have stayed in the past — and fallen — with Nazi Germany.

The National WWII Museum says that still relevant, too, is this quote from Josef Kohout and "The Men with the Pink Triangle": "What does it say about the world we live in, if an adult man is told how and whom he should love?"

The last survivors of the original pink triangles have died

In 2011, The New York Times announced the death of 98-year-old Rudolf Brazda (pictured), thought to be the last survivor of the gay men sent to concentration camps to be identified with a pink triangle. The German-born Brazda had spent three years in Buchenwald, and was there for liberation. He — like many — lived a post-war life in obscurity, and only came forward as a survivor in 2008, at the unveiling of Berlin's German National Monument to the Homosexual Victims of the Nazi regime.

Brazda shared his memories in several books documenting his experience. He recalled: "Seeing people die became such an everyday thing, it left you feeling practically indifferent. Now, every time I think back on those terrible times, I cry. But back then, just like everyone in the camps, I had hardened myself so I could survive."

There were still other survivors of German persecution, like Wolfgang Lauinger. He had been jailed during the Third Reich for being one of the Swing Kids — the polar opposite of the Hitler Youth — and post-war, he was one of many arrested in a massive police raid that led to what became known as the Frankfurt Homosexual Trials. He was released, but became a stalwart campaigner for justice for those who had been imprisoned. DW says that he passed away in 2017: The 99-year-old activist was never granted the reparations that he had worked so long to get for all those persecuted under Paragraph 175.