Why A Lot More Babies Have Been Born In Antarctica Than You Think

We've only been sending humans to Antarctica for about 100 years, according to Royal Museums Greenwich. Various explorers sailed around the southern continent at times in the 1700s and 1800s, but it wasn't until 1895 that the first ship landed there, setting into motion a century of exploration, according to New Zealand History.

Of course, no one stayed in Antarctica for long. The land is inhospitable to human habitation in the extreme, and the early explorers were presumably quite happy to return home. Today, the landmass is a destination for people keen to study astronomy, climate change, or the continent's unique ecosystem, among other things, and it houses about 82 bases, according to Antarctic Glaciers. Still, the population of the continent has never exceeded a few thousand people, and indeed, when the Antarctic winter comes in March, bringing with it six months of total darkness, only one thousand "winterers" brave the season, the rest having long since gone home.

You would think that Antarctica is not the place for children, and generally, you'd be correct. The scientists and support staff who work there are all adults, and those who have families leave them at home. Nevertheless, 11 babies have been born on the continent over the decades, in misguided political attempts at colonization.

Keeping Antarctica Neutral

Two competing schools of thought (and one international treaty) govern what goes on in Antarctica, both in a practical sense and a philosophical one. In a practical sense, the world treats the continent as a neutral space, "reserved for peace and science," as the U.S. State Department describes it. The place has no government, according to Visual Capitalist, although a committee meets every couple of years to talk things over. There is no exploitation of fisheries or natural resources there, and of course, great care is taken to preserve the pristine environment of the continent. The Antarctic Treaty of 1959, to which 53 nations are signatories, is the legislative basis for the current system, according to the State Department.

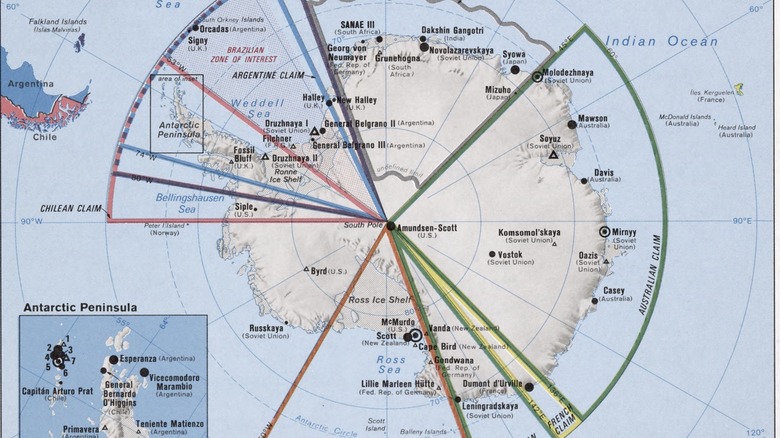

However, none of that has stopped seven nations from making claims to sections of Antarctic territory. Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom have each claimed a slice of the continent, emerging at the South Pole and extending into the Southern Ocean, as their own. However, those claims mean nothing in a practical sense, with research bases and the scientists working on them scattered here and there across the continent with zero respect paid to those claims. Further still, according to the State Department, neither the U.S. nor "most other countries" recognize those claims.

But, what if there was a practical way to solidify those claims? Back in the 1970s, a couple of South American dictators took their shots.

A Practical Solution To A Philosophical Problem?

Quite a few legal matters, both picayune and of major international significance, depend almost entirely on being taken seriously. For example, Maryland has a law against adultery, but no one remembers the last time it was enforced, and police and the judicial system don't take it seriously. Similarly, a person or a nation can make a claim — ownership, sovereignty, mineral rights, whatever — to a landmass but it won't make any difference if other nations don't recognize it.

Now, here's a thought experiment: If you are going to claim a piece of land for yourself, how can you convince the rest of the world that your claim is legitimate? One way would be to start exploiting the landmass' resources, for example. Another way is to colonize it — that is to say, send settlers there who will populate it and, ideally, start producing more colonists through reproduction. This is one of the factors that helped the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, and multiple other nations become colonies and, later, independent nations.

Colonizing Antarctica is not an option, of course, because of its inhospitality to human habitation. However, if a nation sent one mother down there to have one baby on Antarctic soil (or snow), then theoretically anyway, step one towards colonization has been checked off, and the nation has a bit of a stronger claim. At least, that's what two South American dictators thought for a time in the 1970s.

A Tale Of Two Dictatorships

The map pictured above shows that the southern tip of South America is pretty close (relatively speaking) to the northern reaches of the Antarctic landmass. That bit of South America also represents the southernmost limits of both Chile and Argentina.

Back in the 1970s, Chile and Argentina were both governed by dictatorships who wanted to make names for themselves, and both saw solidifying their claims to Antarctica as a way to make that happen, according to Atlas Obscura. The ball got rolling, so to speak, when Chile's Augusto Pinochet made a state visit, of a sort, to the continent to press Chile's claim. Argentina's then-ruling military junta were not best pleased, and in late 1977, sent Silvia Morello de Palma, who at the time was seven months pregnant, to Argentina's Esperanza Base, according to NZ Herald. On January 7, 1978, the first Antarctic baby was born. The Chileans, undeterred, then sent a married couple to conceive, gestate, and give birth to a baby. Then the Argentines sent a couple, then the Chileans, and so on, until 11 babies were born (some also conceived and gestated there) on the continent, according to Medium.

The end result of all of this was a whole lot of nothing, as neither Argentina nor Chile ever managed to convince the rest of the world that the landmass is theirs, babies or no. And, of course, both dictatorships are now things of the past.

The Antarctic Babies Today

The first baby born in Antarctica was Emilio Palma, according to Atlas Obscura, on January 7, 1978. As of this writing (May 2022) Palma would be a 44-year-old man, however, it's unclear what he's doing now. The Chilean baby who was conceived, gestated, and born in Antarctica was Juan Pablo Camacho Martino, born on November 21, 1984, according to Web Ecoist (he is equally elusive when it comes to alerting the world to his movements). The last baby born in Antarctica was a Chilean (or an Antarcticer, if you want to recognize Chile's claim), Ignacio Alfonso Miranda Lagunas, born on January 23, 1985. And, it seems he too would like to remain out of the public eye.

Why the Antarctic baby race came to an end is unclear, but the fact that no one outside of Argentina or Chile was taking the matter particularly seriously certainly played a role. And, of course, it goes without saying that the environment there is simply not suitable for raising children.

Meanwhile, in a weird data point in the history of pediatrics, all of the 11 babies born in Antarctica survived infancy, meaning that the continent is the only one on Earth with a 0% infant mortality rate.

Pregnancy And Medical Care In Today's Antarctica

It's been decades since the last infant was born in Antarctica, but the fact remains that the continent is populated by both men and women, and men and women are going to do what men and women do. As WorldCrunch reports, the agencies that supply the Antarctic bases make sure to include plenty of condoms to prevent Antarctic pregnancy. And, if a woman does turn up pregnant in Antarctica, she's put on the first available flight back to civilization, according to Jezebel. The reasons for this are obvious: The continent simply isn't equipped to handle prenatal care, abortion, or other issues related to pregnancy, gestation, and birth. As for how many women have landed in Antarctica and left with a bun in the oven, that's not clear, although anecdotal reports suggest it's happened at least twice.

In addition to sending pregnant women home right away, the agencies that send people to the continent test women for pregnancy before they get on the plane (or ship, as the case may be). Anyone who refuses, or who tests positive, isn't allowed to proceed.

"No one wants to become pregnant down there, no one wishes a baby to be born down there. I think it would just put that much bigger burden on the station and the station medical officer," said a physician who has worked there.