The Crisis Of Missing And Murdered Indigenous Women In America Explained

Throughout American history, Indigenous women have been in danger from men. The concept of "manifest destiny" decreed that American — usually white — men were destined to expand throughout the rest of the country and tame it. The history of relations between the American government and indigenous tribes that lived on the land before there was a central government is not kind. History paints America as the winner even though such atrocities as the Trail of Tears. However, indigenous women are still exploited today, taken from their communities against their will, and murdered.

The media doesn't take as much notice of this crisis as it should, and differing jurisdictions for reservation land muddle things up (via The Seattle Times and CNN). Police departments are often overly busy, and evidence can be hard to find, according to The Guardian. On the other hand, negative stereotypes also cause people to look less closely than they should — or normally would — if the victim was white (via Native Hope and The Seattle Times).

People continue to get their cues regarding indigenous women from the media, both news programs and fictional entertainment. Most prominent fiction treats Native American women harshly: They are either murdered, raped, or otherwise exoticized on screen, to the subsequent negative treatment of their real-life counterparts (via Women's Media Center). Let's take a look at the reasons for this crisis that many would prefer to turn away from — which is honestly the first problem in and of itself.

Colonialism and subjugation began the problem

The subjugation of American Indigenous people was the beginning of the crisis many indigenous communities now face — colonialism and racism merely exacerbated the problems that quickly overtook certain communities. There are records showing that one of Christopher Columbus' crew members raped an indigenous woman, showing that the problems stretch back that far throughout history, writes Peter Stearns in "Sexuality in World History." In fact, most European explorers quickly judged indigenous women as "loose and immoral," with many of their behaviors catalogued as erotic. Homosexual and bisexual actions among Native peoples were also considered devilish from a European standpoint.

As time wore on and European men began to bring their wives to the Americas, indigenous women began to try to fight back against rape and other sexual harassment. Their reputations usually ended up in tatters, and they were rarely successful in the courts. Most women found that it wasn't worth the trouble. Europeans thought that impure Native women were able to be raped without concern because they were without integrity, quite like prostitutes. Andrea Smith's "Not an Indian Tradition: The Sexual Colonization of Native Peoples" writes that sexual abuse now towards Native women affects them on two counts, as it serves as an attack on their identities both as a woman and an indigenous person. Ultimately, Smith writes, as long as white people in positions of power want the use of mineral-rich reservation land, sexual exploitation of Native women will continue.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Rural, confusing jurisdictions

Local and state police have to contend with tribal police and policies for cases, which can get confusing, as cases can get lost in the mix, according to CNN. The rural nature of some cases means that there is often precious little information or evidence to go on; some reservations don't have police officers at all. When there are tribal police, they are often understaffed or unsure whether they are responsible for solving these cases due to confusion around statutes (via CNN). With little information coming in about cases and few people to work on them, it's no surprise that this issue is as big as it is.

"The resources are spread so thin, it allows people to fall through the cracks," said Billy J. Stratton, an expert in Native American studies at the University of Denver, via CNN. Washington State, meanwhile, is depending on its state police to begin to beef up their databases on missing and murdered Indigenous women. Unfortunately, state police usually have no recourse to get personally involved in a case on a reservation unless it relates to a non-Native person. The FBI has also been invited by tribal police to investigate particular cases.

Male-dominated industries nearby

Environmentally-damaging industries (such as logging, mining, and working with fossil fuels) bring male workers to rural places for long periods of time, who live together without girlfriends or wives nearby. It has been observed that rates of crime and assault go up during these times as well, writes Greenpeace. For example, the oil boom of the 2000s and 2010s in North Dakota also included at least 125 filed cases of violence and assault against Indigenous women in the state, though the number was likely higher in actuality.

The Sovereign Bodies Institute began a database and recorded 529 cases in the past several years throughout the states of North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Montana — where the Keystone oil pipeline would travel and therefore where oil pipeline workers were living (via Greenpeace). Ultimately, some argue that both capitalism and the rural, male-dominated nature of this kind of work exacerbate the crisis facing Indigenous women and their families.

Lack of resources for police departments

Police departments are often understaffed or nonexistent in rural areas, writes CNN. They have hundreds of cases and must prioritize what they can. Federal law didn't allow Native American nations to prosecute non-Natives for decades, which meant their tribal police departments couldn't manage most of the cases regarding missing and murdered Native women since many of those crimes were perpetrated by non-Native men (via Indian Law Resource Center).

According to The Guardian, police officers have also been slow at times to start an investigation. Thus, families usually start the search themselves, with law enforcement following behind. Family members have also felt slighted by police officers who dismissed their concerns, asking if their missing relative was simply out partying. Cases have also simply not been recorded in the first place or recorded incorrectly; many Native women have been misclassified in records as being of a different ethnicity (via The Guardian). With many cases already in their laps, officers likely don't take much time to figure out what happened to cases that never got reported properly in the first place.

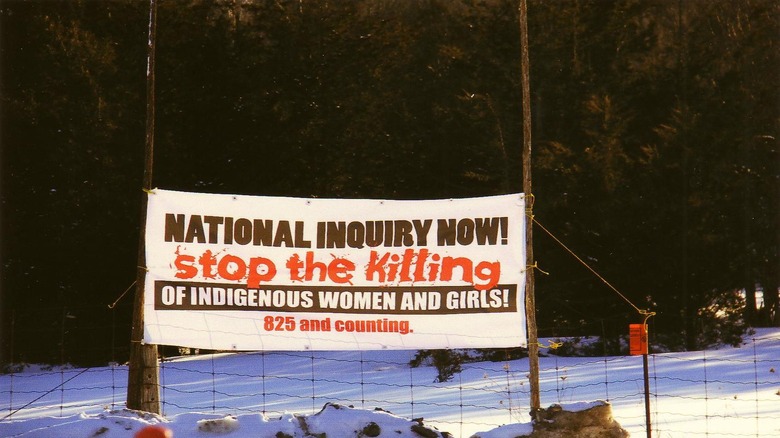

Lack of databases

Most states have little data on the Indigenous women crisis, which makes the issue harder to track. The true number of missing and murdered Indigenous women in the U.S. is unknown. The lack of data also lends credence to the idea that the crisis isn't that widespread, despite studies suggesting otherwise. According to MPR News, someone would have to systematically speak to every tribe across the U.S. to get a full scope of what's happened over decades.

According to Times-Standard, one reason data is lacking is because Indigenous women are often misclassified as being of a different ethnicity; their cause of death is also often added to the system incorrectly. "There's always been significant problems and significant undercounting, and there are still those problems across the country," Yurok Tribal Court Chief Justice Abby Abinanti told Times-Standard. The publication notes that several California tribes had their federal protections taken away from them in the late 1900s, so victims during that time could have been misclassified as white due to their tribes not legally registering; it's unknown whether victims were then reclassified correctly after their tribes was given back their rights.

Certain important data is simply not collected by state or federal law enforcement. For example, many sex-trafficked minors came out of the foster care system, which is a relevant statistic that isn't collected, writes Times-Standard. Other collected data isn't available to tribes or researchers, even if they request data through the Freedom of Information Act.

Lack of media attention

The media does not cover cases when indigenous women are missing nearly as much as cases covering missing white women. For example, the Gabby Petito case in 2021 was much more widely covered, supporting accusations of racial bias against indigenous women. According to The Seattle Times, the disparity is the epitome of "absolute injustice."

An Internet search of Petito's name revealed 340 million results, in contrast to missing Indigenous woman Mary Johnson, whose name landed 6,000 search results, writes The Seattle Times. National attention has been launched over missing white women such as Laci Peterson, while cases of missing Indigenous women go largely ignored; perpetrators certainly take this point in mind. After all, why not go after the women no one is going to look for?

"What we see is systematic bias, institutional and structural racism and the vilifying and the placing of blame on the victims themselves and their families for when these people go missing and murdered," Abigail Echo-Hawk, director of the Urban Indian Health Institute, told The Seattle Times when discussing missing and murdered Indigenous women. She continued, "We need to do better. Our women should not go missing. They should not be invisible. We deserve justice, and we deserve for the families to know what happened to their loved ones."

Frustrating interpretation of statutes

The statutes that make up the law on the authority of Indigenous peoples are confusing, given that they are based on previous laws during times of colonization; Different interpretations also make for different outcomes. According to National Indigenous Women's Resource Center, the laws are outdated and prevent the government from fully protecting indigenous women.

Many laws were predicated on the religious rights of the European power colonizing the land. Soon after the United States was created, the federal government took control of Native American affairs. Two statutes from the 1800s decreed federal control over Native Americans who committed crimes against people who were not Native American; frustratingly, this out-of-date approach makes up a section of the current law, according to the National Indigenous Women's Resource Center. The 1885 Major Crimes Act statute was also misinterpreted for decades as saying that tribes had no authority over committed crimes. It wasn't until the 1990s that this was cleared up, and it was made plain that Native American tribes did have authority over investigating crimes along with the government (via National Indigenous Women's Resource Center).

There have been several reports over the years taking the federal government to task for their failures to protect tribes, not to mention the restrictions tribes exist under. Though those reports offer solutions, few of them at the state level — let alone the federal level — have been taken up and passed into law.

Media's depictions of rape and brutalization don't help

The film and television industry doesn't feature indigenous women often, but when it does, they are often raped, murdered, or written in as a magical native savior, writes Women's Media Center. These depictions add to the view that these women are here for men to use them. They are also more exoticized and sexualized than white women, making them easy targets for men, both figuratively and literally.

The film and TV industry has also engaged in whitewashing to continue the spate of harmful racism by way of the idea that assimilation works. This is not a new concept, and it's even more awful in the modern era. Native women aren't featured much, and in that sense, says Apache actress Joanelle Romero (via Women's Media Center), "If we don't matter, it doesn't matter when people rape and murder us. I addressed this to a group of Hollywood executives, and they said, 'You can't blame this on us,' and I told them, 'Yes, I can.'"

Though Native Americans are creating their own media via acting, writing, and creating other art, there is very little market for such work. Things might be starting to change, but the process is slow.

People think stereotypes perpetuate wrongdoing

Negative stereotypes often play a part in the media failing to report on this crisis, as well as police moving slowly. According to families, police officers victim blame, telling worried family members that their loved one will likely come home in a few days or that they are simply out doing drugs or partying, which ignores the critical early window for finding them, writes The Seattle Times. Media stories are also often written in a negative fashion when speaking of the victim, making it seem as though they are in the wrong, as seen in this letter to the editor of the Capital Journal. Louise Lola Bear Stops, who was found dead in South Dakota in 2020, was written about in the publication; however, the only thing significantly mentioned was her past criminal record.

According to Native Hope, America has collectively written a stereotype-laden story about Native Americans: they are lazy drunkards who use government assistance to live their lives. Since that story is so easy to fall into, those stereotypes make it so much harder for anyone other than the victims' families and communities to do anything about this crisis.

Urban poverty badly affects indigenous people

Many indigenous people live in urban areas where they fall in with other vulnerable people, such as those who are homeless, young people exiting foster care, or other people of color, writes Native Hope. Living in a city offers little assistance from the tribal community, tribal law enforcement, or family members when in times of trouble. Poverty is another challenge that goes hand in hand with violence and sexual assault toward indigenous women.

The Guardian recounted several stories of Native Americans who live in cities rather than on reservations. One woman and her son were homeless activists, while many struggled to relate back to their culture. Growing up off the reservation made Isabella Zizi feel that "we are a minority mixed within a minority group," according to The Guardian. One young woman participated in the Standing Rock protests, and many others participated in some kind of community Native American organization. Nevertheless, several women had experienced violence, assault, rape, or alcoholism somewhere in their past or family. One woman also experienced severe racism across much of the country before she and her family settled in the San Francisco Bay area. Though poverty might affect Native Americans, they aren't letting it stand in their way.

This crisis is broader than most people think

A 2016 National Institute of Justice study found that 84 percent of American indigenous women had experienced violence in their lifetimes, according to the U.S. Department of the Interior. Since this issue is not covered much by the media, people don't realize just how widespread it is.

A commonly cited statistic is that for indigenous women living on reservations, the murder rate is 10 times higher than the national average (per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, via Urban Indian Health Institute). Though it is often tossed out, really considering the implications of that piece of data leads to horrifying results. Men have high rates of victimization as well, and investigations into human trafficking among Indigenous people led to the realization that more could and should be done on this issue. Many victims experienced shame and refused to come forward (via U.S. Department of the Interior).

The National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Center began a database project to fully document how many American Indigenous women have experienced physical or sexual violence in their lives. The project found that more than half of all Indigenous women experienced the latter, and over half of the physical violence was perpetrated by partners these women were already intimate with. Specific regions and states have even higher rates of violence and sexual assault. This issue is huge, and most people only see the tip of the iceberg.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

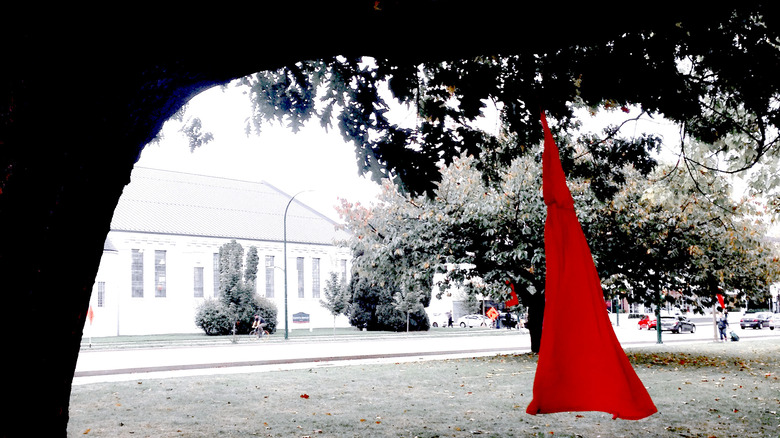

How women are fighting back against MMIW

Many different centers are raising awareness of the crisis by gaining resources and creating systems to protect indigenous women and girls as best they can. The Indian Law Resource Center raises awareness of the crisis by partnering with other organizations for specific projects — some directed toward the federal government — and also provides legal services to Native American women and organizations that need them. The center is also working to continue to revise and better U.S. law and help protect its indigenous women and girls so they can bring their perpetrators to trial.

Native Hope, similarly, is working to spread awareness of missing and murdered indigenous women through a short film, Voices Unheard, and by bringing more political attention to the crisis. Representative Deb Haaland of New Mexico has cited MMIW (missing and murdered Indigenous women) as an issue she has based her political campaign on. Native Hope considers itself to have a platform, resources, tools, and a voice in the fight.