The Messed Up Truth Of The Edgewood Experiments

From at least 1948 to 1975, the U.S. Army was involved in human experimentation involving chemical agents at Edgewood Arsenal (via the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs). But over half a century later, they continue to be less than forthcoming about the experiments, even with their own subjects. And while information has slowly trickled out over the years, the military and Department of Veterans Affairs have done their best to try to evade responsibility at every turn.

For years, these experiments were kept a secret even from the soldiers who were being tested on. After years of being evasive, the U.S. Army was finally forced to admit that they were conducting chemical tests on human subjects. But while they've always insisted that the subjects were volunteers, the lack of documentation regarding these experiments makes it questionable if the people involved were actually giving their full and informed consent.

This isn't the first time that the United States government has experimented on its own citizens. But many of their experiments had their origins at Edgewood. Even the well-known Project MKULTRA had its budding start at thee facility. This is the messed-up truth of the Edgewood experiments.

Creating the Edgewood Arsenal

The Edgewood Arsenal facility, located in the U.S. Army Aberdeen Proving Ground in Aberdeen, Maryland, was built during the end of the First World War to study and weaponize chlorine and mustard gas. After breaking ground a year earlier, by October 1, 1918, the Edgewood facility had over 585 buildings, a hospital with over 250 beds, and barracks for 8,500 officers and enlisted men (via "Environmental Histories of the First World War"). The New Yorker writes that the U.S. Army promptly built laboratories and gas chambers in order to run experiments on human subjects after witnessing the effects of chemical warfare during WWI.

According to "The Chemist's War" by Gerard J. Fitzgerald, by the end of the First World War, the Edgewood facility was "the most advanced chemical weapons facility in the world and the only facility capable of producing all four of the Great War's war gases [chloropicrin, phosgene, chlorine, and mustard gas]." In 1918, The Baltimore Sun described it as "the largest poison gas factory on earth." At least one private also wrote in 1918 about hearing "about the terrors of this place [...] Everyone we talked to on the way out here said we were coming to the place God forgot! They tell tales about men being gassed and burned."

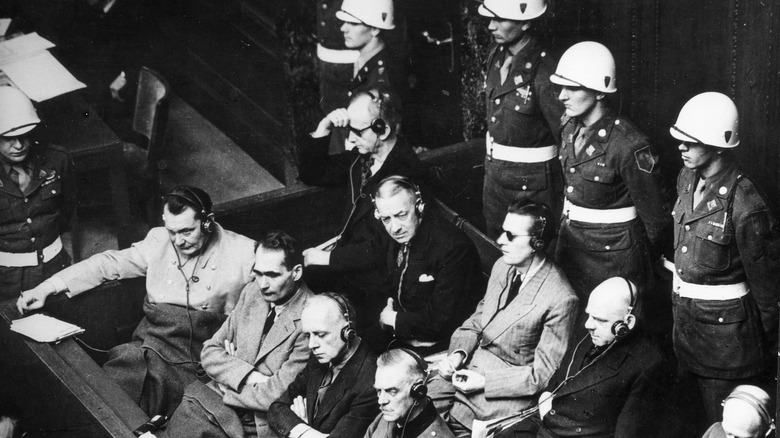

Recruiting Nazi scientists

After the Second World War, the U.S. Army put some of its efforts toward studying the nerve gasses that the Third Reich had invested in, including tabun, soman, and sarin. According to The New Yorker, both the Soviet Union and the American governments were interested in acquiring Nazi knowledge about chemical weapons. While the Soviet Union reportedly relocated a nerve-gas plant behind the Iron Curtain, the Americans recruited the Nazi scientists who developed the chemical formulas.

In "Hard Right Turn," Jerry Carrier writes that many Nazi doctors and scientists were recruited by the United States as part of Operation Paperclip, and many were brought to the Edgewood facility. And most of the scientists brought over had already been identified as Nazi war criminals during the Nuremberg Trials. "Several secret U.S. government mind control projects grew out of these Nazi experiments at the Edgewood Arsenal. These projects included Project Chatter in 1947, and Project Bluebird in 1950 [later renamed Project Artichoke]," Carrier writes.

Recruited scientists included Freidrich Hoffman and Dr. Karl Tauboeck, who were both involved in chemical experiments for the Nazi Reich. The Alliance For Human Research Protection writes that not only did they continue working on chemical experiments for the U.S. Army and CIA, but they also conducted tests on soldiers using oxygen deprivation. A CIA memorandum noted that "some subjects became exhilarated, talkative, or quarrelsome, with emotional outbursts or fixed ideas. Some complained of headache or numbness. Voluntary coordination and attention are impaired ... burns and bruises are not noticed."

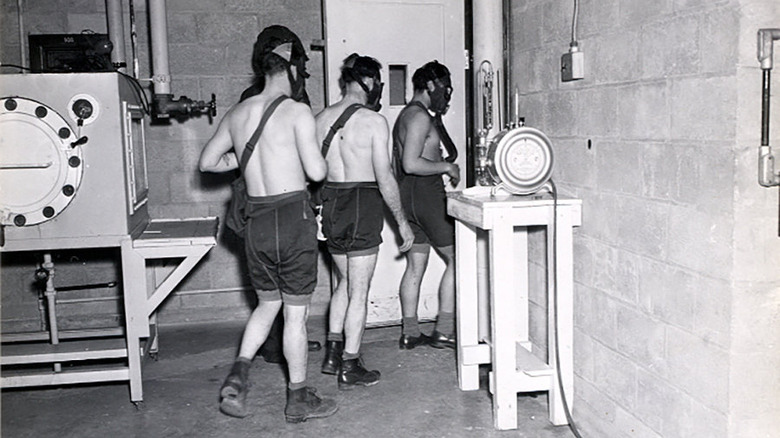

The Edgewood Arsenal human experiments

Along with the testing of nerve gasses, L. Wilson Greene, Edgewood's scientific director, reportedly wrote in 1949 that psychochemical warfare was the next stage of warfare. "Throughout recorded history, wars have been characterized by death, human misery, and the destruction of property; each major conflict being more catastrophic than the one preceding it. I am convinced that it is possible, by means of the techniques of psychochemical warfare, to conquer an enemy without the wholesale killing of his people or the mass destruction of his property," he wrote the classified report "Psychochemical Warfare: A New Concept of War," per The New Yorker. As such, this became the foundational understanding behind the Edgewood facility, and in order to manifest this new concept of warfare, thousands of people were experimented upon between 1948 and 1975.

Estimates of how many soldiers were used in human experiments by the U.S. Army and the CIA vary. According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, up to 6,720 service members participated in chemical experiments involving over 250 different chemical agents. The All Native Group's Ho-Chunk Technical Solutions Healthcare Division conducted a report — Assessment of Potential Long-Term Health Effects on Army Human Test Subjects of Relevant Biological and Chemical Agents, Drugs, Medications and Substances — that found that 12,000 men in the military were used in human experiments for biological and chemical warfare programs. Meanwhile, the 1993 and 1994 reports by the U.S. General Accounting Office state that "hundreds of radiological, chemical, and biological tests were conducted in which hundreds of thousands of people were used as test subjects."

Informed consent?

Although some sort of consent form was given to the service members at some point, it's questionable if any of the soldiers were fully informed about the experiments they were participating in. NPR reports that while the soldiers did sign consent forms, they didn't know what they were being exposed to, and "some of the soldiers have suffered physical and psychological trauma since the tests." The 1994 General Accounting Office report on human experimentation also notes that many of the people subjected to the human experimentation "complained that they had not been fully informed about risk involved," according to "Military Neuroscience and the Coming Age of Neurowarfare" by Armin Krishnan.

The 1975 U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Health and Subcommittee on Administrative Practice and Procedure also found that "the consent information was inadequate by current standards," per Possible Long-Term Health Effects of Short-Term Exposure to Chemical Agents. But according to The Baffler, informed consent has never really been extended to people in the military. Court cases like Chappell v. Wallace, Feres v. United States, and United States v. Stanley have repeatedly set the precedent that the state has broad immunity from wrongdoing when it involves people in the military since any damages are considered to be "incident to service."

Nerve agents

Experiments involving nerve agents at the Edgewood facility were already in progress by July 1953. According to the U.S. Army Inspector General's report on the "Use of Volunteers in Chemical Research," the experiments included exposing nerve gas liquid to human skin and nerve gas vapor to the respiratory tract, studying the effects of nerve gas on nervous and mental functions, and comparing the effects of nerve gas liquids, vapors, and aerosols on skin.

The Baltimore Sun reports that some of the tests involved releasing nerve agents in open-air testing, and while the subjects were dressed in protective suits and masks in some of the tests, "not all of them were informed that chemical and biological agents were being used." It's also unclear how many people were involved in these experiments. Open-air testing of toxic agents was banned in 1969, but indoor tests reportedly continued until 1981.

According to "Medical Aspects of Chemical Warfare," the U.S. Army also conducted nerve agent testing experiments in Hawaii between 1966 and 1967.

Mustard agents

Mustard agent was also used in the human experiments at the Edgewood facility in various forms. Acutely toxic levels of mustard liquid were reportedly used and would often cause immediate poisoning symptoms. And according to Military Medicine, the rate of documented injuries was incredibly high. At one point over a two-year period, over 1,000 cases of acute mustard agent toxicity were reported. Experiments were also conducted using gas chambers, and they often lasted between one to four hours. People who were given less protection often suffered from "severe burns to the genital areas, including cases of crusted lesions to the scrotum."

Although these experiments were more common at the Edgewood facility during the Second World War, they continued well after the conflict ended. Some service members were only notified in 1996 that they'd been a participant in mustard agent testing, per the "Chemical Weapons Exposure Project: Summary of Actions and Projects." In addition, NPR reports that sometimes, the experiments were also grouped by race "to see what effect these gasses would have on black skins."

Psychoactive agents

In addition to chemical agents that could be used during warfare, the U.S. Army also tested numerous psychoactive agents on soldiers at the Edgewood facility. The New Yorker reports that psychochemical warfare was officially added to Edgewood's research roster in the mid-1950s, and soldiers were recruited from all around the country using the Medical Research Volunteer Program. (Many of these experiments can also be linked with Project MKULTRA.) According to Military Medicine, LSD was tested on at least 741 people, while PCP was tested on at least 260 people. "With rare exceptions, all LSD-exposed subjects [reportedly] voluntarily participated in the chemical warfare testing and were informed ahead of time that they would be receiving a psychoactive agent," the U.S. Army Chemical Corps and the U.S. Army Intelligence Corps claimed.

But Army Master Sergeant James B. Stanley was one of the many people who wasn't informed of the fact that he was being used to test LSD. The Baffler writes that in the winter of 1958, Stanley was given water secretly infused with LSD once a week for over four weeks in addition to being injected. Even after leaving Edgewood, Stanley continued to suffer reactions to the druggings, sometimes manifesting in violent behavior. He wouldn't discover the cause of his behavior until 1975, when he received a letter from the U.S. Army asking him if he'd like to participate in a study of long-term effects of LSD on volunteers from the 1958 tests.

Riot control agents

Riot control agents, including irritants and blister agents, were also tested at the Edgewood facility. Military Medicine writes that about 1,500 people were involved in the human testing experiments of riot control agents, including CS, chloropicrin, Adamsite, and other ocular and respiratory irritants. Exposure was typically through aerosol, dermal, or eye application. For some people, exposure to CS lead to erythema, vesicles, burns, hepatic dysfunction, and urinary abnormalities. Some even showed allergic dermatitis after repeated exposure.

According to "Celebrating 85 Years of CB Solutions," the Edgewood facility was instrumental in supporting the Vietnam War with riot control agents. Even the Army Research and Development wrote in 1968 that Edgewood developed three munitions that were being used in Vietnam "with very good results." Meanwhile, "Inhalation Toxicology," edited by Harry Salem and Sidney A. Katz, notes that the United States doesn't recognize riot control agents to be chemical warfare agents.

The Report of the Comptroller General of the United States also confirms that during at least one point, the U.S. Army also used dogs in their "experiments on new nonlethal riot gasses."

Government revelations

The 1975 report by the U.S. Army Inspector General on the "Use of Volunteers in Critical Agent Research" was one of the first official revelations regarding human experimentation at the Edgewood facility. And NPR reports that in 1975, the military's chief of medical research admitted that they didn't have any way to monitor people's health after the tests were done. Further confirmations came in the 1980s, when the Institute of Medicine produced a three-volume report at the Army's request regarding the long-term health of Edgewood veterans entitled "Possible Long-Term Health Effects of Short-Term Exposure to Chemical Agents." According to CNN, the Institute of Medicine determined that there wasn't enough information to form "definitive conclusions."

In 1993 and 1994, the General Accounting Office reported on the human experimentation at Edgewood Arsenal as well as the human experimentation at the Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, Fort Benning, Fort Bragg, and Fort McClellan. But considering the limited information provided by the U.S. Army, the General Accounting Office concluded that "precise information on the scope and the magnitude of tests involving human subjects was not available, and the exact number of human subjects might never be known."

In 2004, the General Accounting Office also determined that although some of the people used in human experimentation were eventually identified and informed of their contact, there were likely "service members and civilian personnel potentially exposed to agents who have not been identified for various reasons."

Lack of a paper trail

The 1975 report by the U.S. Army Inspector General called "Use of Volunteers in Critical Agent Research" writes that "the lack of factual information available to quickly respond to the inquiries illustrated an inadequacy of the Army's institutional memory on this subject area. This inadequacy was aggravated by inconsistencies in the limited data which was available." These sentiments were echoed by the General Accounting Office. The IG report also notes that many of the requests for experiment approvals failed to even mention what specific nerve gas agents would be used under which circumstances. "The available records gave the impression that the submission of the initial request[s] amounted to nothing more than a perfunctory action for the purpose of obtaining blanket approval for ongoing research projects," it reads.

According to the "Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists," the U.S. Army also failed to provide any follow-up medical care and failed to anticipate any long-term health consequences. And even when veterans like Nathan Schnurman, a Navy test veteran, continued to suffer from long-term health problems and got the Department of Veterans Affairs to admit that human experimentation had occurred on him, he was unable to get them to admit that it had any relation to his current health problems. Even the Navy records he was able to find were "erroneous and incomplete."

Veterans et al v. the CIA et al

In 2009, a group of veterans organizations filed a suit against the CIA and the United States Department of Defense, stating that the government was obligated to contact all their subjects of the human experimentation and give them proper medical care. The Guardian reports that while the veterans acknowledge that they volunteered for the experiments, "we were not fully aware of the dangers. None of us knew the kind of drugs they gave us or the after-effects they'd have." Instead, they were told that the experiments were harmless and that their health would be monitored throughout the tests as well as afterward.

NPR reports that a court ruled in favor of the veterans in 2016, but the U.S. Army has reportedly been "falling short of meeting its obligations and that it's withholding details veterans are seeking about what agents they were exposed to." And rather than sending veterans an account of their medical history, the army has sent out form letters that state that the recipient may be eligible for medical care if they previously volunteered for "medications or vaccines."

Long-term effects

Although the three-volume study published by the Institute of Medicine between 1982 and 1985 claimed that there were no "significant long-term health effects in Edgewood Arsenal volunteers," many veterans have reported experiencing long-term health effects that can be attributed to the human experimentation at the Edgewood facility (per the "Deployment Health Support Directorate"). Unfortunately, NPR reports that many who participated in the experiments have also since passed away.

Black Then writes that many servicemen suffered from a variety of adverse health effects following the Edgewood human experiments, including peeling skin, cancer, motion disorders, and psychological issues. And although many veterans meet all of the requirements to apply for benefits if they can prove that they have an illness linked to a chemical the U.S. Army exposed them to, NPR reports that the Department of Veterans Affairs continues to press for more information and proof and will deny benefits to veterans for decades.

Per NPR, though veteran Harry Bollinger, who participated in the human experiments, is proud of his service, "that time in his life is tainted: by the pain he felt as a human test subject in military experiments, and by the VA that told him it wasn't real."