Scientists Think They Figured Out Where The Black Death Started

Over the course of a few years, beginning in the late winter of 2020, the world was made acutely aware of just how devastating contagious, microorganism-borne illnesses can be. The COVID-19 pandemic has, as of June 2022, claimed 6.3 million lives worldwide, including over 1 million deaths in the United States (via World Health Organization).

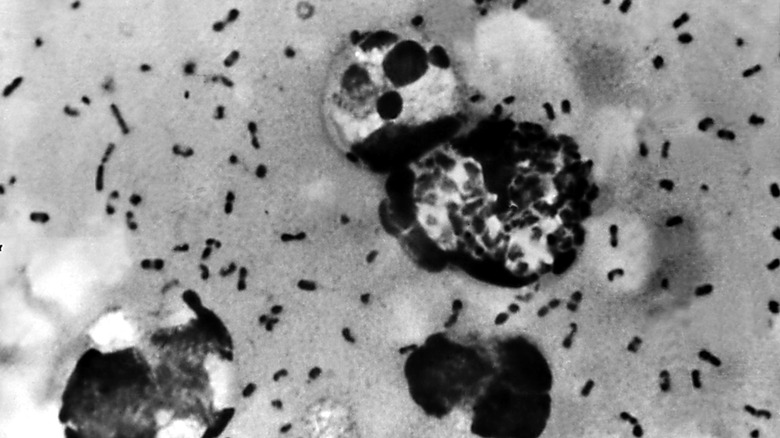

Centuries before coronavirus, another contagious illness claimed not just a few million lives but tens of millions of them, particularly in Europe and West Asia. The Black Death (or alternately, the Black Plague or the bubonic plague) was caused not by a virus, but by a bacterium — Yersinia pestis, according to the Centers for Disease Control — probably carried by rats and then transferred to humans via the fleas that bit those rats and then bit humans.

These days, health officials are keen to identify an emerging contagious illness and identify where it originates and how it moves, ideally so they can get out in front of it before it becomes an epidemic. And though it's centuries too late for the people of Europe, in June 2022, researchers announced what they believe is the place where the Black Death originated.

How The Black Death Kills

Once the Yersinia pestis bacterium has entered the victim's bloodstream — usually through the bite of an infected flea, per Healthline — the organism then enters an "incubation period" of a couple of days, during which the victim shows no symptoms. Then, the sickened individual will show flu-like symptoms. The victim may then develop oozing, painful boils — buboes, they're called, leading to the name "bubonic plague" — which would typically develop on the arms or groin of the victim or near the site where they were initially bitten.

According to ScienceDaily, the disease kills by cutting off communication between the victim's cells and their immune system, leaving the diseased individual unable to fight off the infection. Eventually, the victim will go into septic shock and multiple organ failure (via RealClearScience). Victims usually die, slowly and painfully, within about three to five days after initially showing symptoms, according to History Today. Further, about 80 percent of the people who contracted the illness in those days died from it.

The Spread Of The Black Death

Though the Bubonic Plague of Europe between 1347 and 1351 was, at the time, the biggest and most wide-ranging pandemic of the disease up until that time, it was neither the first nor the last plague to be caused by the Yersinia pestis organism, according to Britannica. Centuries earlier, the Justinian Plague of the middle of the 6th century decimated Europe, and it came back with a vengeance centuries after in the 1600s, according to the British National Archives.

The spread of the disease, in all three cases, could be tied to travel: specifically, warfare and trade. Invading soldiers carrying the disease brought it to communities they attacked or traveled through, and in fact, in one early act of biological warfare, a general catapulted the bodies of plague-infected corpses into a city he was invading. Similarly, shipping ports, such as Venice, would become infected when ships would pull into port, and the disease spread from there.

Scientists have concluded that rats on those ships would carry the bacterium, and fleas would bite those rats and then bite humans. The cramped living quarters, generally poor health, and inadequate hygiene of the day made European humans a veritable petri dish for the spread of the illness.

Did It Originate Near A Lake In Central Asia?

The Black Death came to Europe (not for the first time) in or around 1347, according to the New York Times. However, a few years earlier, it was killing people in Central Asia, and we know this because Philip Slavin of the University of Stirling in Scotland and his team studied a graveyard in what is now Kyrgyzstan. Specifically, according to CNN, the team looked at the graves near Lake Issyk-Kul (pictured above) and found that their inscriptions, written in an ancient language known as Syriac, not only provided the exact year of the deaths of the bodies below, but that several of them died of "pestilence." Most of the graves were marked either 1338 and 1339 — just a few years before the plague struck Europe.

That's as close to a Holy Grail as anyone is going to get when it comes to this sort of archaeological epidemiology, says Slavin. "When you have one or two years with excess mortality, it means that something was going on. But another thing that really caught my attention is the fact that it wasn't any year — because it was just seven or eight years before the (plague) actually came to Europe," he said.

DNA from the bones of the victims were sent for study, and sure enough, they contained genetic traces of the dreaded Yersinia pestis. Further still, a nearby village was populated by traders, meaning that the region may have been the birthplace of the second plague.

The Same Strain Was Found In London Plague Victims

It wasn't just the plague itself that was found within the bones of the victims dug up in the Kyrgyzstan cemetery — it was (possibly) the same strain. We're leaving out considerable archaeological, epidemiological, and microbiological nuance here, but long story short: Scientists believe that Yersinia pestis evolved into at several strains — a "big bang," as CNN calls it — at some point before the disease reached Europe.

As the illness was emerging in what is now Kyrgyzstan, thousands of miles away, the people of London were going about their business. However, when news of the plague ravaging Europe reached England, the authorities knew that it would only be a matter of time and started preparing mass graves in advance, according to The New York Times. Scientists later exhumed some of the bodies from the London graveyard and sequenced their DNA. To simplify: The Kyrgyzstan forms the "trunk" of a tree that eventually evolved into four different branches, one of which wound up in Europe a few years later.

The Plague Is Still Around

Though it's been centuries since the death toll from the bubonic plague was in the millions, the bacterium that causes it — Yersinia pestis, pictured above — is still around. Further still, it continues to sicken people to this day.

As the Cleveland Clinic notes, outbreaks of the plague are still a routine occurrence, although obviously not on the scale of what happened in Europe in the 6th, 14th, and 17th centuries. Specifically, outbreaks occur pretty routinely in Africa, Asia, and South America. The bacterium even lives in and infects people in the United States. About seven Americans, on average, get sickened with it every year, mostly in the Southwestern portion of the country.

Fortunately, thanks to modern hygiene practices and our understanding of epidemiology, health officials are ahead of the curve when it comes to managing this illness. And even when someone does get infected, modern antibiotics can clear it up pretty routinely, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.