The Fine Arts Were An Olympic Competition For Decades Before They Were Banned

The Olympics, to put it mildly, have changed a lot over the millennia.

Historical records reveal Olympic games were held in Greece in 776 B.C., though it is likely they were already an established tradition by then (via History). Said to have been founded by the demi-god Heracles (Hercules in Roman parlance) and taking place at a city called Olympia, the games were a hugely popular centerpiece of a festival honoring Heracles' father Zeus. Not only did the original games have a religious connotation, for a long stretch women were not allowed to participate. According to an historian from the 1st century B.C., the 15th Olympics saw the first naked sprinters (via History News Network). Different sources claim different origins of this trend, from a desire to run faster to loincloths representing a tripping hazard.

The games were held every four years for over 1,000 years, continuing under Greece's Roman occupiers until A.D. 393, when the empire, embracing Christianity as an official religion, declared the games pagan and banned them (via History). The sacred event that brought the footrace, the javelin and discus throw, long jump, boxing, wrestling, and more to the Mediterranean masses nearly disappeared from history.

But some 1,500 years later, the Olympics were resurrected — with an artistic twist.

The Olympics Reborn

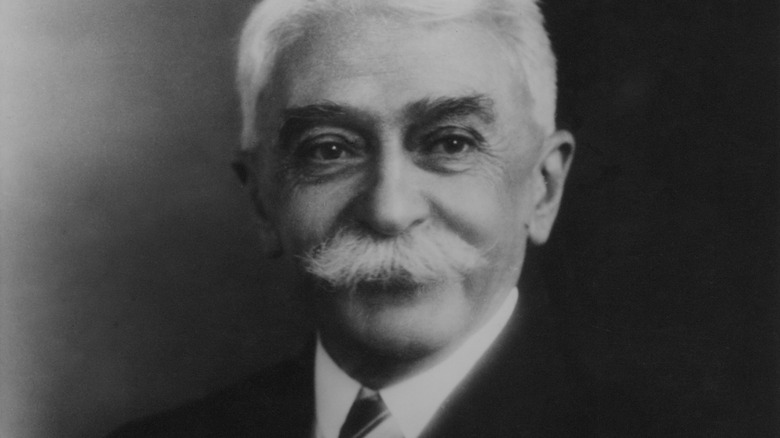

The Greeks restarted the Olympics in Athens in 1859. According to Britannica, Greek philanthropist and businessman Evangelis Zappas put it together, though others were calling for this beforehand. A few decades later, the French educator Pierre de Coubertin and English doctor William Penny Brookes brought together international organizations to bring the games to the world — the first modern Olympics took place due to their efforts in Athens in 1896.

It was Coubertin who led the charge for the new Olympics to be more than just physical contests. According to Smithsonian Magazine, he wanted art competitions included to elevate the games over other sporting events, and while he did not get his way in the beginning, by 1912 there were medals for architecture, painting and sculpture, literature, and music. Coubertin also wanted to pay tribute to the ancient Olympics, which had competitions of heralders and trumpeters (via the Historical Dictionary of the Olympic Movement).

Though always overshadowed by the spectacle of the races and sporting events, the arts (always with a required sport theme) were a staple of the Olympics through the 1940s. Over 150 medals were awarded, including a gold medal to French sculptor Paul Landowski, who would go on to create Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro (via Olympics.com).

The arts competitions ended not from lack of popularity, but due to a change in leadership and philosophy.

The End of the Arts

When American sports administrator Avery Brundage became president of the International Olympic Committee in the early 1950s, he sought to oust the arts, feeling that the games were being used in an inappropriate way to advance professional careers (via Smithsonian Magazine). He disliked the fact that winning a medal could lead to more art sales for competing artists, as if the games were simply a vehicle for them to advance their financial interests. The Olympic games were supposed to be the crowning achievement for competitors, not a stepping stone. It was about what the games represented, and the meaning behind a victory. Further, how fair was it for amateur artists to compete with professionals (via The Atlantic)?

The IOC Congress agreed that the Olympics were for amateur competitors, not professionals (via Olympics.com). Thus, the fine arts were retired as categories of competition. (Ironically enough, the Olympics would increasingly abandon amateurism and open up more and more to professional athletes, according to The Atlantic.)

However, the leadership did not eliminate this tradition entirely. Today, each Olympics has a non-competitive art exhibition.