The History Of Cartography In Ancient China Explained

Before smartphones, GPS, or even MapQuest (remember that?), and for thousands of years before any other kind of gadget would help us find our way around, there were maps — and out of China came some of the oldest and most advanced ancient maps around. Just ask the Library of Congress.

The maps of ancient China take the form of everything from splendid paintings on paper or silk, to wood carvings or stone monoliths that educated generations of students and passersby, all wanting to know where exactly they were on Earth. Many were also surprisingly advanced, with some depicting epic voyages in lavish detail. Others were meant to show exactly how far imperial power had reached, as well as enabling accurate oversight of tax collection, flood control and military defense.

A new adventure unfolds as this history of Chinese maps winds through struggles for power, faraway lands, and the imperial courts of dynasty after dynasty.

The history of cartography in ancient China begins with legends

What was supposedly the first Chinese map is shrouded in legend. According to ChinaKnowledge.de, it makes its first appearance in the tale of Emperor Yu the Great, a supposed demigod also known as the Tamer of Floods, and founder of the first Xia Dynasty. He is often depicted fighting floods, as shown in a jade carving from the Palace Museum in China's Forbidden City.

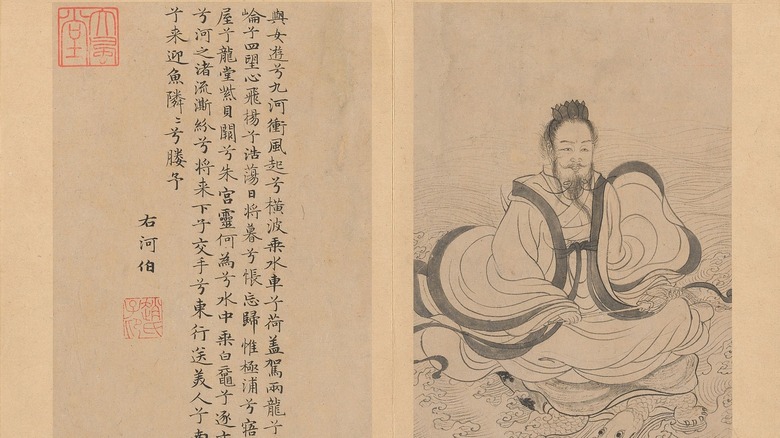

According to legend, Emperor Yu held back the flooding of the Yellow River after being handed what is known as the "River Chart," or "Hetu," by its resident deity He Bo, who was dreaded because he was able to drown the land in tremendous floods. Another map associated with Yu the Great is the "Yujian" ("Jade Tablets"). This map was inscribed in jade and given to him by Fu Xi, another deity whose human torso ended in a dragon's tail. It was because of these maps that he was said to have been able to figure out where to dredge the river, and where to dam it.

Whether or not the Xia dynasty actually existed is debatable, according to National Geographic. It might have been a myth invented by a later dynasty, to prove that they had earned the throne from the successors of the Xia, said to have come into power because Yu the Great's feats made the gods grant him emperor status. However, Chinese archaeologists have since unearthed ancient evidence of flooding which aligns with accounts describing the Xia era, from between 2070 B.C. to 1600 B.C.

The earliest Chinese maps might be some of the oldest ever found

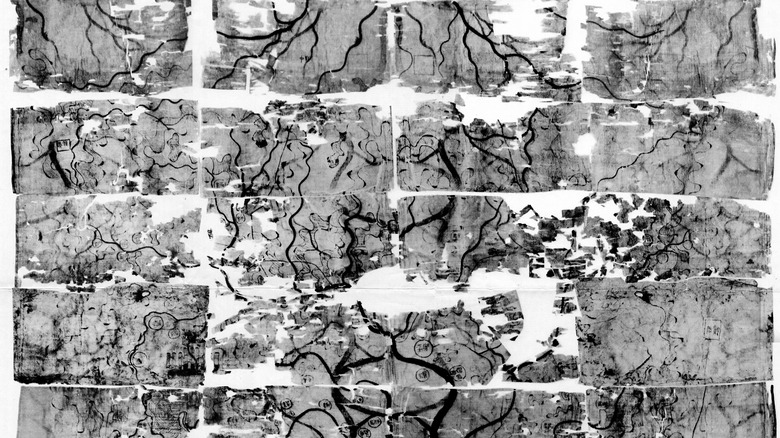

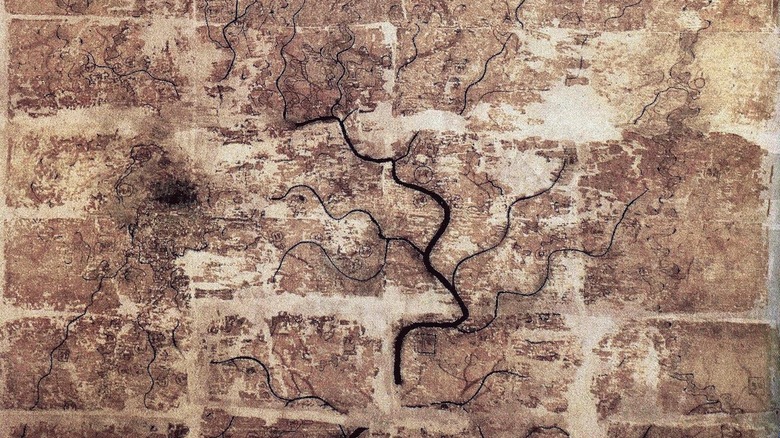

While Chinese records dating back thousands of years mention maps, when exactly cartography started in China remains a mystery. When three Han Dynasty tombs were excavated in late 1973 (one of them revealing the amazingly preserved mummy of Lady Dai, per Discover), three silk maps also surfaced, according to geographer Chen Cheng-Siang in his study "The Historical Development of Cartography in China," who believes they are among the oldest ever unearthed.

While one of the 2,150-year-old maps — of a walled-in city — degraded more than the others and is still being examined, it became obvious that one of the remaining two was meant to be topographical, and the other used for military defense. Both are thought to have been created around the same time and mapped the same region near the province of Hunan. Many details — even the colors of the ink — on these maps survived thousands of years of being entombed. Cheng-Siang writes that they are "surely the best maps that the world has ever retrieved from its remote past."

As geographer Mei-Ling Hsu notes in her study "The Han Maps and Early Chinese Cartography," published in Annals of the Association of American Geographers, the Han Dynasty maps are not only relics of the second century B.C., but they also predate the second-oldest Chinese maps by 1,300 years. The only maps found to be older are Babylonian clay tablets.

Not all maps were on paper

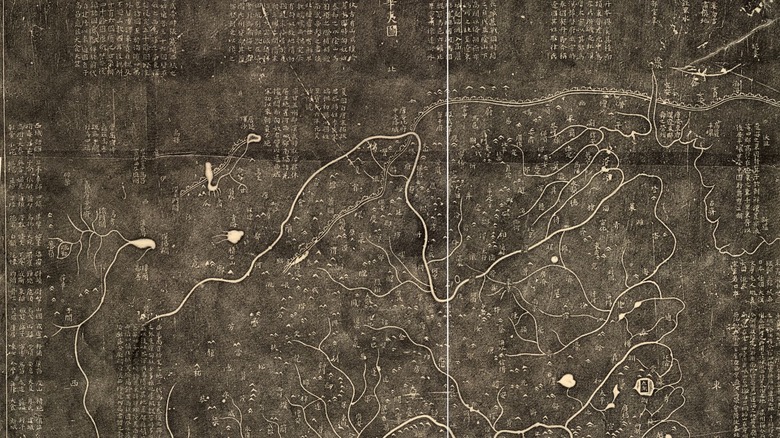

Some ancient maps were literally set in stone. The "Hainei Huayi Tu" ("Map of Chinese and Non-Chinese within the Seas") and "Yijitu" ("Map of the Tracks of Yu" — also a tribute to the flood fighting Emperor Yu) had been engraved onto a stone stele, according to Geographicus.

"Hainei Huayi Tu" was also the first map to show China's place in the world, by identifying surrounding territories at the edges of its nine regions, as historian Hilde de Weerdt points out in her book "Information, Territory and Networks: The Crisis and Maintenance of Empire in Song China." China was viewed through this map as more than a kingdom — it was now seen as an empire.

The double-sided stone obelisk which still has these maps inscribed on the front and back is, according to map collector David Rumsey, an actual monument in itself. This made it easy to reproduce them on paper by making rubbings against the carvings. Both in and out of the imperial court, maps made of stone, wood, metal, and even earth were common during the Tang and Song Dynasties, according to de Weerdt. Having a stone map also allowed anyone passing by to educate themselves about the land they lived on, from rivers to mountains, and beyond.

Roads need maps, and empires need both

Emperor Qin Shi Huang unified the unstable territories of China, according to Britannica, but then needed to figure out what to do about roads. In "The Historical Development of Cartography in China," Chen Cheng-Siang notes that the Qin government amassed as many maps as possible to help create a network of roads leading to the imperial capital, so it could be better defended — Qin did not want any of the territories acting up.

The Qin empire was massive, and into its expanse Qin Shi Huang built 4,000 labyrinthine miles of road, including the 500-mile-long "Straight Road," which History calls a "superhighway" and assisted the construction of the Great Wall of China. None of this could have been done without maps as guides.

When future emperor Liu Bang and his forces rebelled against the Qin capital, at the dawn of the Han Dynasty, his adviser Xiao He would seize these maps, according to ChinaKnowledge.de. It was later during this dynasty when the maps would make their way to royal minister Pei Xiu, who Cheng-Siang calls "the first reputed cartographer in China." Xiu would eventually become the reigning godfather of Chinese mapmaking and would scrutinize those maps, using them to create more consistent and accurate versions.

There was an actual godfather of maps

When Pei Xiu noticed that maps were not realistic enough during the Jin Dynasty, he decided to change them himself. He came up with six principles which were incorporated into future Chinese cartography. The Yu Gong Diyu Tu ("Tribute of Yu," that was yet another Yu the Great homage) was his compilation of maps, now mostly lost. However, according to historian Cordell D.K. Yee's book "History of Cartography," a piece of it copied into a later work survives.

Pei Xiu's six principles, as Yee lists them, are "proportional measure (fenlü), standard or regulated view (zhunwang), road measurement (daoli), leveling (or lowering) of heights (gaoxia), determination of diagonal distance (fangxie), and straightening of curves (yuzhi)." This was supposed to be an improvement on previous maps that were incomplete, and sometimes featured phantom landmarks. Fenlü was supposed to help readers make out the distance between things, zhunwang made sure locations were accurate, and daoli helped gave an idea of where exactly you were on the road. The rest — gaoxia, fangxie, and yuzhi — used geometry to get mountains and other aspects of the terrain correct.

Because of how he revamped cartography, Pei Xiu has been immortalized as "The Chinese Ptolemy," as Jerry Brotton says in his book "A History of the World in Twelve Maps."

Spectacular maps showed epic voyages

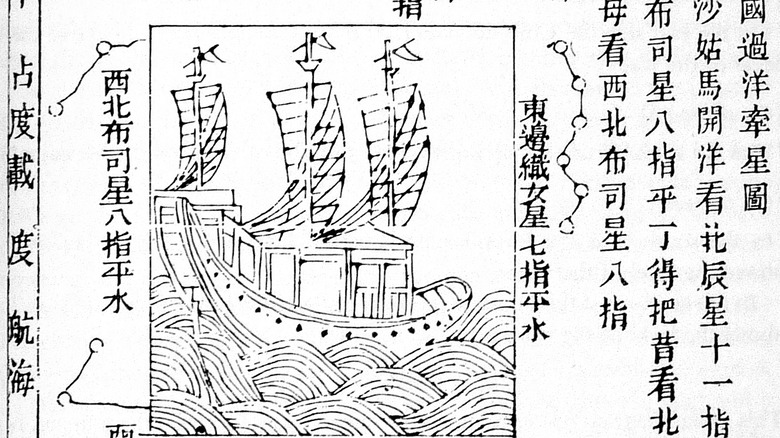

The seven legendary voyages of explorer and admiral Zheng He are seen by the World History Encyclopedia as a display of the Ming dynasty's tremendous wealth (to impress other nations Emperor Yongle of China wanted diplomatic relations with). He led the lavish imperial fleet from Vietnam to Sri Lanka, India, all the way to the Persian Gulf, and Africa, to establish diplomatic relations with the rulers of those countries. In "History of Cartography," Yee calls this China's "greatest achievement in navigation," and Mao Yuanyi turned Zheng's travels into what became known as the Mao Kun map.

After Xuande succeeded Yongle and took the throne, he temporarily continued to fund Zheng He's undertakings, as World History Encyclopedia also notes, but soon needed to close off China because of the Mongol threat. There would be no more grand expeditions for a while. For those who wondered what far-off lands were like, the Mao Kun map would remain a window to the outside world in the years that followed. You can see an interactive version of the map created by faculty at the University of California at Santa Barbara. It not only shows the paths which Zheng He took, but visuals of the majestic landscapes of China and beyond, marking prominent locations along the way.

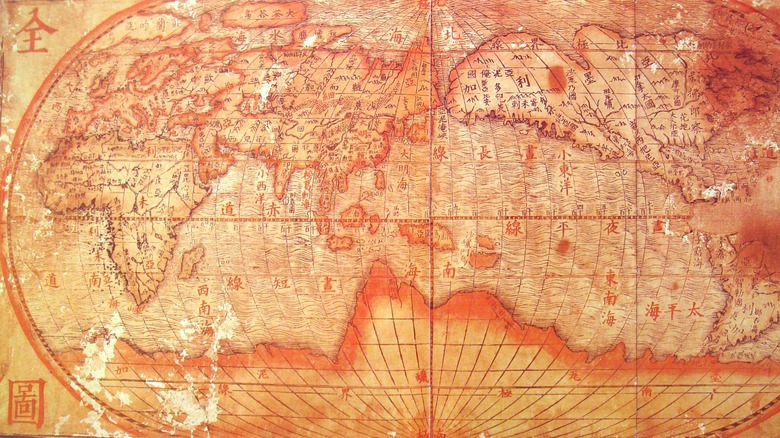

Some maps suggest the Chinese may have discovered the Americas

A sea voyage made by the Chinese explorer Zheng He, in 1421, may have gone much further than the generally accepted boundary of Africa. The New York Times says a map, claimed to be from the same period, offers the tantalizing possibility that the Chinese discovered what is now America, well before modern Europeans. In his book "1421: The Year China Discovered the World," historian Gavin Menzies says "Lost was the knowledge that Chinese ships had reached America seventy years before Columbus and circumnavigated the globe a century before Magellan."

Menzies also claims that the Chinese had discovered Australia and Antarctica, and that Chinese DNA has been found in certain indigenous groups from both the Americas and Australia. But how did a copy of Zheng He's map lead them there? Whether it actually did is controversial. Simon Jenkins of The Guardian believes that at least some parts of the map are "plainly a hoax," and points out that the dead giveaway is how North and South America, along with Australia, New Zealand, and Antarctica, are drawn accurately when "no sailor could possibly have known" what they actually looked like back then.

Not everything on the map is realistic: California appears to be a massive island, for example, which Jenkins recognizes as a common mistake made during the 17th century. For some reason, whatever that may be, the already fantastical travels of Zheng He may have been exaggerated.

Chinese maps spanned continents

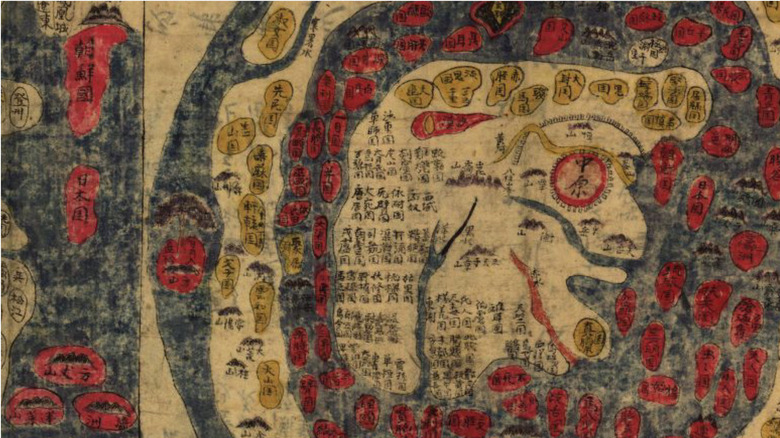

Another Ming Dynasty map that was born of an international voyage was "Da Ming Hunyi Tu" ("Amalgamated map of the Great Ming," a copy of which is held in the Library of Congress), created to visualize where China stood politically at the time. The empire might have not stretched all the way to the Americas, but as Alexander Akin says in his article "The Da Ming Hunyi Tu: Repurposing a Ming Map for Sino-African Diplomacy" (via Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review), it stretched far enough to show evidence of China's political relationship with South Africa. They were apparently on shaky terms: the Chinese had ditched efforts towards a strong diplomatic relationship, instead trying to get as much trade in as they possibly could.

This map has often been mistaken as another Zheng He spinoff, but Akin reveals it was actually based on imported Middle Eastern maps. Unlike Zheng, whoever used "Da Ming Hunyi Tu" had not created it from experience, but from observation of other maps.

Maps also facilitated imperial power

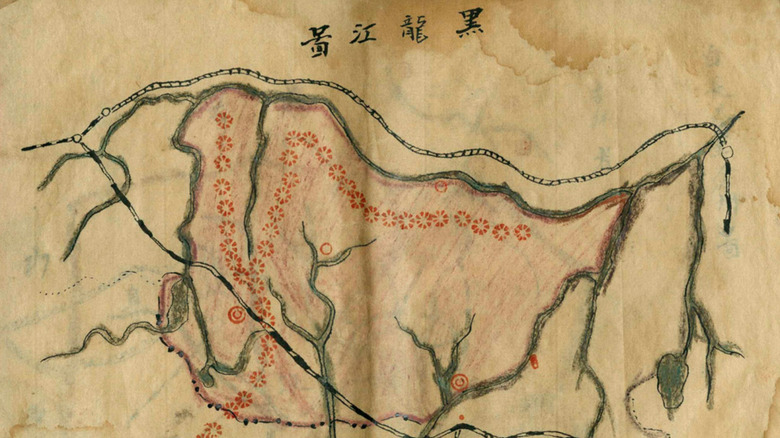

During the Qing Dynasty, maps began to be used as visuals for what regions China was conquering and how it continued to expand, according to Harvard University. Knowing roads and borders of other territories was also an advantage when it came to the empire asserting its power. The Qing Empire's "Map of the New Domination," "Complete Map of All Under Heaven," and "Map of the Borderlines of China and Russia" showed just how far the empire reached. Harvard University further delves into "Map of the Borderlines of China and Russia," an attempt by the Chinese to translate Russian cartography into their own methods so they could understand where Russia began and their own empire ended.

In her study "Qing Connections to the Early Modern World," published in Modern Asian Studies, historian Laura Hostetler states that maps were made during the Qing dynasty "as part of its process of expansion" and that they "at once facilitated and justified its colonial policies." These maps show how the empire succeeded in expanding as much as it did, and she also argues that the way they showed this was similar to the way expansion was depicted in contemporary European maps. Hostetler asserts that Qing mapping techniques were "part of, rather than isolated from, the early modern world."

A disgruntled ex-court official created the first Chinese atlas

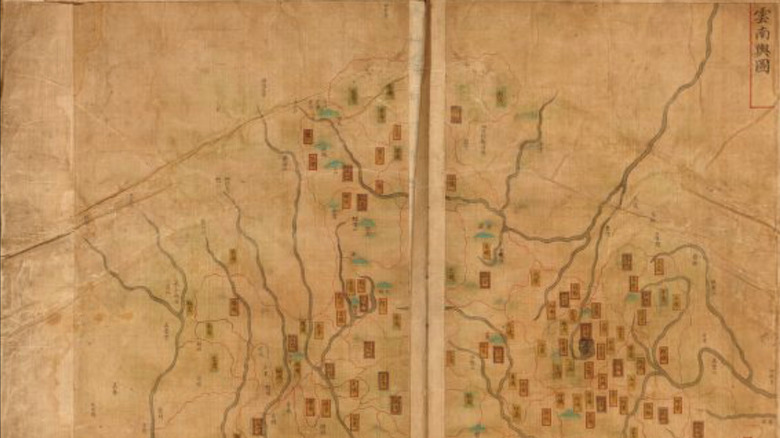

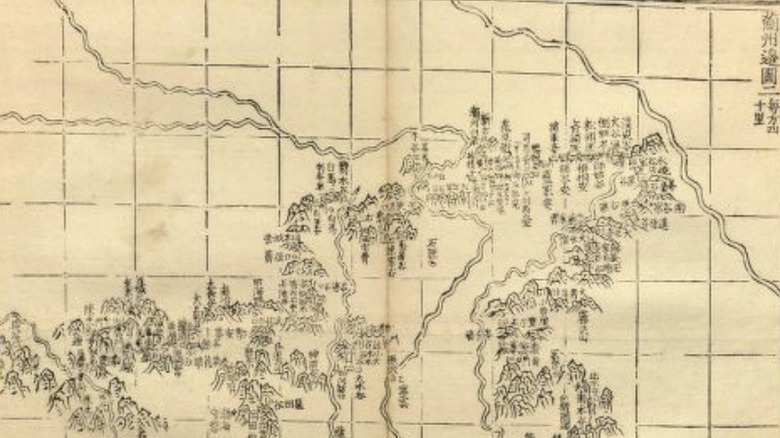

Put together enough maps and you get an atlas. The "Guang Yu Tu" ("Unfolded Terrestrial Atlas") is the oldest complete atlas of China, according to the Library of Congress. It was created by Ming dynasty cartographer Luo Hongxian, who modeled it after the legendary but vanished "Yu di Tu" ("Terrestrial Map") of Zhu Siben, who lived during the Yuan dynasty.

Hongxian was appointed senior compiler in the imperial court. Though the court officials managed to push him out, he responded by further studying the arts and sciences, especially cartography. Zhu Siben's older map inspired him to create something unprecedented. According to some scholars, such as Li Gang in his article "The Chinese Invention of [a] Bi-Hemispherical World Map," via e-Perimetron), Hongxian was impressed by how Siben had created a map in which the Earth was a sphere, evenly divided into the northern, southern, eastern, and western hemispheres. The only problematic thing about the Yu di Tu map was that its dimensions made it "difficult to handle," as Hongxian said, according to Gang. Whatever his motivations in fact were, by drawing maps on a grid and binding them into an easier to use atlas, "Guang Yu Tu" was a real innovation for its time.

Mapping eventually became a science

According to Lin Meicun's "A Study on the Court Cartographers of the Ming Empire," published in Journal of Asian History, there were no official imperial cartographers during the Ming dynasty, and court artists created maps instead. They could pull off impressive landscapes — but some important items were missing. Even the map that was supposed to depict the extent of the dynasty had no scale, so no one using it would know what distances they were looking at.

This is where Jesuit missionaries came in, although, as stated in "History of Cartography," by Cordell D. K. Yee, "It was not the primary aim of the Jesuits to train the Chinese in European science and technology." But where most Jesuits backed off, missionary Matteo Ricci saw an opportunity. Ricci thought introducing the Chinese to European arts and sciences would make it easier to convert them to Christianity. Ricci applied the latest European cartographical techniques, incorporating a spherical Earth, to create maps that also absorbed the traditional perspectives that the Chinese held at the time, such as placing China in the center of the world, and including Chinese writing. These were considered impressive by many Chinese intellectuals, who began to use them as references for their own maps.

Eventually, Chinese and European maps would merge

Traditional Chinese cartography methods did not fall into obscurity during the Ming and Qing dynasties. As P. Liu and Y. Hu say in their study "The Comparison of Cartographic Culture Between China and the West," published by the International Cartographic Association, some Chinese methods were for a long time superior to those used by Western Europeans, such as using compasses for accuracy — and the Chinese had invented paper long before Europeans.

Starting in the late Ming, during the "unification of art and science" in cartography, as Hu and Liu put it, cartographers would use the best techniques, from both cultures, to their advantage. They had begun to take on the European point of view that saw Earth as a sphere and mapped locations accordingly. According to Cordell D. K. Yee in "History of Cartography," Chinese cartographers started to see their methods as something to base the more European execution of their maps on, satisfying "the impulse to fuse the two cultures," as exemplified in the "Da Qing yitang yutu (Comprehensive geographic map of the Great Qing, 1863)."

This didn't mean that 5,000 years of Chinese tradition faded out: through their interactions with Europeans and other cultures, cartographers in China were only adding to their already vast knowledge. As Hu and Liu go on to say, "Through comparison to find the differences and identities of the maps of China and the West, this process would promote mutual understanding and unification."