Fritz Kolbe: The German Diplomat Who Spied For The Allies In WWII

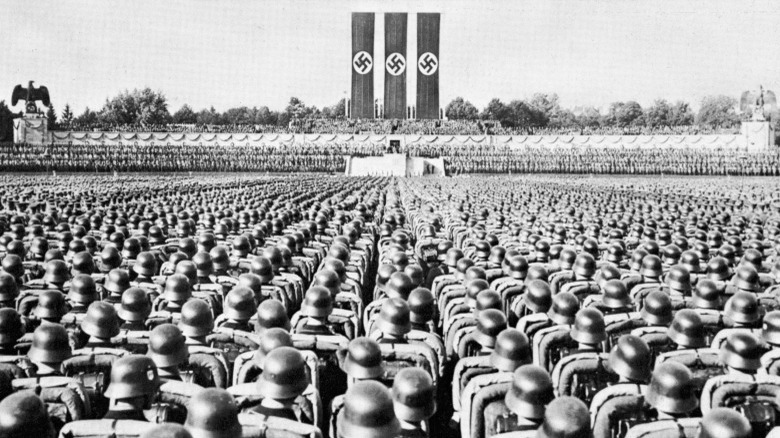

The 1930s and 1940s were dark times for many of the citizens of Germany. The Nazis infamously rose to power in the early 1930s and ushered in over a decade of terror and horror –- mainly directed at the Jewish, disabled, and Romani citizens of Europe. The Nazis slaughtered over 11 million victims during the Holocaust and occupation of Europe, forever shattering countless families and households (per the National WWII Museum).

However, there were some in Germany who tried to stand up to Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party and actively worked to bring them down. One of them was German civil serviceman Fritz Kolbe. Kolbe worked in the diplomatic corps for the German government for two decades starting in 1925, and he started working with the Allies to pass sensitive information on the Nazi war machine in 1943 (per the German Resistance Memorial Center). Kolbe hated Hitler's regime, and he thought spying on the Germans would end the war and the Nazi party's control on power as early as possible. He died in 1971, never being officially recognized for his contributions during his lifetime.

Joining the Wandervogel movement

Fritz Kolbe was born in 1900 to a small family in Berlin, Germany. His father was a saddle maker who taught his son to always stand up for what was right even in the face of fear (per Prologue Magazine). In 1914, when he was just a teenager, WWI broke out and Germany was immediately thrust into chaos. At this time, Kolbe joined what was known as the Wandervogel movement, which rejected what they saw as the materialistic value system of the bourgeois in Germany.

According to Walter Laqueur in "Young Germany: A History of the German Youth Movement," the Wandervogel youth (pictured above) used romanticism to protest society and materialism. They "rediscovered old folk songs and folklore," and they gave themselves new medieval names and habits. They often went on hikes, both to escape their parents and connect more deeply with nature — similar to boy scouts. After WWI, many German youth groups started to join the infant Nazi youth movement, the Hitler Youth, but the Wandervogel sternly rejected Nazi ideology (per Prologue Magazine). They would come into violent conflict at times with pro-Nazi youth groups, like the Sturmabteilung, but refused to submit or join the Nazis — foreshadowing Kolbe's later choices to spy for the Allies in WWII.

Serving in the German Army and joining the civil service

When Fritz Kolbe was just 17 years old he found himself conscripted into the German army during WWI. He served as a civilian in a telegraph unit for almost a year before becoming a soldier in August 1918 (via Prologue Magazine). After the war, Kolbe found himself apprenticing for the German state railways and taking night classes at the University of Berlin. He was studying for the civil service and foreign service examinations, which he passed in 1922 and 1925, respectively.

Kolbe got married in 1925, before being reassigned from the railroad to the German Embassy in Madrid, Spain, later that year. He left Madrid during the Spanish Civil War and started working in Cape Town, South Africa, in 1938, until he was ordered back to Berlin in late 1939 with the outbreak of WWII. When he returned to Berlin, he left behind both his new wife (his first wife passed away) and son. According to a Boston Globe interview with his son Peter in 2001, the elder Kolbe and Peter would spend nights burning sensitive documents before his father returned to Germany. During his time in the civil and foreign service, Kolbe developed a good reputation for precision and work ethic, though he was not very well liked by most of his colleagues (per James Srodes in "Allen Dulles: Master of Spies").

He refused to join the Nazi party his entire life

As incredible as it may seem for a career diplomat in the German government in the 1930s, Fritz Kolbe never joined the Nazi Party. He saw the party rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s, but thought them to be "liars who tried to fool everybody," and refused repeated overtures to join (via Prologue Magazine). Several times Kolbe found himself under interrogation from party officials about his reasons for not joining, but he was never reprimanded or punished. A 1935 personnel evaluation of Kolbe leaked to the Spanish newspapers during his time in Madrid, which considered him unfit for party membership due to his ties with "Marxists and Jews." Privately, Kolbe was elated upon hearing about it.

While he was serving in Cape Town, South Africa, from 1938-1939, he started to socialize with anti-Nazi circles in the city (per Prologue Magazine). He was paranoid that he might be found out and have to escape at a moment's notice, so when he returned to Germany he took multiple passports and official stamps, and even a pistol. He wanted to shield his son from the abusive Nazi ideology, so he had him stay in South Africa when he returned to Berlin.

Kolbe formed an underground resistance to the Nazis

Fritz Kolbe found himself in a very uncomfortable position in Nazi Germany once WWII broke out. He was recalled to the German embassy in Berlin to work in the foreign office, but it was a much different foreign office than the one he had worked in years prior (via Prologue Magazine). It was increasingly being filled with Nazi party members, whose politics and ideology Kolbe abhorred.

In response, Kolbe continued his anti-Nazi associations from his time in South Africa. He also reconnected with many of his former Wandervogel colleagues, and together they organized a kind of underground resistance to the Nazis from within Berlin. They wrote letters to banks and businesses informing them of the Nazi's true plans to take over, but they had to be extremely careful. They used gloves to conceal their fingerprints and wrote in block script, but unfortunately some still got caught and were sent to the concentration camps. At one point, Kolbe also used some of the blank passports he had taken with him from South Africa to aid Jewish refugees escaping the Holocaust.

Kolbe tried to get himself reassigned to other countries where he could reveal Nazi secrets, but he was continually rebuffed by Nazi authorities (per Edward P. Morgan in "The Spy the Nazis Missed"). He had even tried to contact "certain Americans in Berlin through church sources" in 1940 before the bombing at Pearl Harbor, but he was unable to get through.

Kolbe worked under infamous Nazi war criminal Karl Ritter

Per Joseph E. Persico in "Piercing the Reich: The Penetration of Nazi Germany by American Secret Agents During World War II," when Fritz Kolbe was recalled to Berlin, he was assigned to work at a diplomatic post under Karl Ritter (pictured above, middle, at the Nuremberg Trials). Ritter was working as a liaison between the foreign office and the German Military High Command at the time, and after the war, during the Nuremberg trials, he would be convicted of war crimes relating to his work there (per the University of Georgia).

At his post under Ritter, Kolbe would sort through the countless cables coming from diplomatic posts around the world to determine which were the most important and sensitive. He often received over 100 cables a day, most of them relating directly to military matters of either the Wehrmacht or Luftwaffe.

He would read the conversations between high officials and foreign diplomats relating to the war, and he also was tasked with reading and summarizing the foreign press for Ritter (per Lucas Delattre "A Spy at the Heart of the Third Reich"). Quickly, he became one of most informed diplomats within the German foreign office.

He started passing information through doctors in 1942

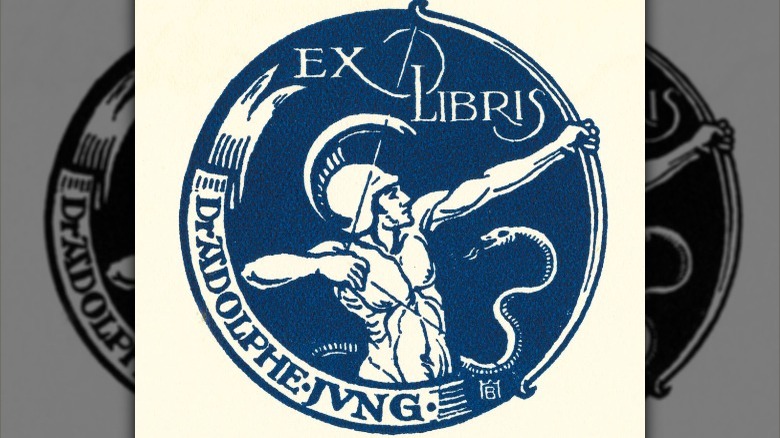

Fritz Kolbe first found himself passing information to the Allies in the Fall of 1942. Within Berlin, there were a few areas of anti-Nazi sentiment, and one of them was the Chirurgische University hospital, which was directed by Dr. Sauerbach — an acquaintance of Kolbe's (per the CIA). At the same time, the German army was drafting Frenchmen into their ranks, and Professor Dr. Adolphe Jung was among those conscripted. However, Dr. Sauerbach was able to get Jung reassigned to a position in his hospital.

Dr. Jung was not just any Alsatian doctor, but he happened to be a supporter of the Free French movement under Gen. Charles de Gaulle, and he also had connections with the French Resistance back home. After Kolbe felt out Jung and realized his anti-Nazi proclivities, he started using him as a liaison. Not only was Jung's office a convenient hiding spot for pilfered documents from the German foreign office, but Kolbe could now start to pass along information through Jung directly to allies in France and London. Thus began Kolbe's official career as a double agent.

His key friendship with Ernest Kocherthaler

When Fritz Kolbe was working abroad as a diplomat in Madrid, Spain, from 1925-1937, he made some important contacts that would serve him well later in life. None more so than Dr. Ernesto Kocherthaler, a German Jew who had immigrated to Spain (per Joseph E. Persico in "Piercing the Reich"). Kocherthaler eventually made his way to Bern, Switzerland, where he would soon see his friend Kolbe again in 1943.

It was not easy for Kolbe to see his confidant in Bern, and it ended up taking him several years to finally get there. First, he tried to arrange a trip to Switzerland under the guise of skiing in the Alps, but he was rejected, partly on the grounds of him not being a Nazi party member (per "The Spy the Nazis Missed"). He was rejected twice more in his attempts a year later.

However, in Spring 1943, Kolbe found his opening. He came back into contact with one of his former Wandervogel colleagues, Gertrud von Heimerdinger. Heimerdinger promised to secure Kolbe a diplomatic mission to Switzerland, and he immediately started collecting cables he was supposed to destroy (via "The Spy at the Heart of the Third Reich"). That August, Kolbe finally made it to Bern with Heimerdinger's help, and he immediately contacted his old friend, Kocherthaler, to help him get in touch with the Allies (via "Piercing the Reich").

He almost blew his chance to help with a disastrous first meeting

After Fritz Kolbe arrived in Bern, Switzerland, and got back into contact with Dr. Ernesto Kocherthaler, he immediately tried to start passing on sensitive information to the Allies. Kocherthaler was quickly able to secure Kolbe a meeting at the British Embassy with attaché Colonel Cartwright (per "Piercing the Reich"). However, Kolbe was erratic and unconvincing in his efforts, and Cartwright flat out told him he thought he was lying.

Both Kolbe and Kocherthaler were discouraged by their initial failure, but Kocherthaler was able to arrange another meeting with Gerald Mayer, a U.S. agent with the Office of War Information. During the meeting, Kocherthaler presented Mayer with several documents labeled Geheime Reichssache, German for secret state documents, and told him he had a source with much more. Mayer was impressed but skeptical, and he talked over the situation with Office of Strategic Services agent Allen Dulles. The two decided it was worth the risk to talk further with the mysterious new source, and another meeting was arranged –- this time with all four men together –- for later that night.

Fritz Kolbe worked with Allen Dulles to start passing information

With the meeting set for midnight that night, both Fritz Kolbe and Dr. Ernesto Kocherthaler made their way to Gerald Mayer's house for their top secret meeting (via "The Spy the Nazis Missed"). Immediately, Kolbe got down to business and presented Mayer with a thick folder containing nearly 200 sensitive Nazi documents. The documents consisted of information on German troops, memoirs from officials, decoded telegrams, and more.

While they were talking, Allen Dulles (pictured above) made his way into the room, and they discussed the documents even further. Kolbe gave the Americans information about potential German spies in Dublin and London, and even gave them intelligence on the complex German cryptography system the Nazis used to encrypt their messages (per "A Spy at the Heart of the Third Reich").

At some point, Dulles and Mayer enquired as to whether Kolbe and Kocherthaler were potential spies, and Kolbe told them exactly who he was in an effort to convince them he was genuine. He explained his position and who he worked for, Karl Ritter, and tried to give them as much assurances about his credibility as possible. When Kolbe told Dulles and Mayer he did not want any payment for his information, they were both aghast. Yet, Kolbe explained his fervent anti-Nazism, and the meeting came to a close.

Kolbe nearly got caught upon his return to Berlin

While Allen Dulles and Gerald Mayer were investigating and confirming Fritz Kolbe's identity and information, Kolbe was headed back to Berlin to continue his work in the German foreign service under Karl Ritter. Once Kolbe returned to Berlin, however, he started to panic (per "The Spy the Nazis Missed"). On his desk was a note ordering him to see the security official "at once" for an interrogation. First, the security official asked Kolbe about his recent trip to Switzerland as a courier. Then he dropped the bombshell: reports had come in alleging that Kolbe had been absent from his hotel for nearly an entire night (the night of his meeting with Mayer and Dulles), what was his explanation?

Kolbe had to think quickly, but luckily he had already planned for just this type of inquiry. He had a certificate dated to that morning, which showed he had gotten a blood test and been given a condom by a local doctor in Bern. The Nazi official let Kolbe go, but implored him to "take care how you waste your time in the future." Kolbe was still safe.

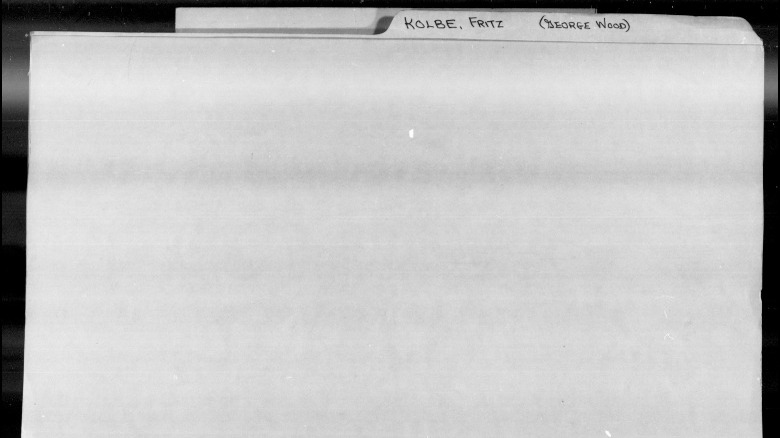

Codename: George Wood

When Fritz Kolbe got back to his hotel room after his meeting with Allen Dulles and Gerald Mayer, his head must have been spinning. Terrified that he was going to be caught and executed for his betrayal by the Nazis, he wrote his final will and testament that night, planning to hand it over to the Americans (per "A Spy at the Heart of the Third Reich"). In it, he showed immense concern for the future of his son, Peter, and listed several potential guardians to raise him in the event of Kolbe's death. He also acknowledged his father, who originally instilled in him the ethical and moral values of righteousness that guided his double agent career.

In his follow-up meeting with Dulles and Mayer the next morning, Kolbe revealed even more information about potential spies in the Allied camps. They next moved to discussing future communication between the two, and various code names were suggested, including "Georg Sommer," "George Merz," and "Georg Winter." After Dulles verified some of Kolbe's story, including having interrogators sent to his son's house in South Africa, he eventually decided on the code name "George Wood," which stuck.

Kolbe was nearly killed by the Allies multiple times

A few months after his initial meeting with the Americans, Fritz Kolbe found himself once again back in Bern, Switzerland, in October 1943. Per "A Spy at the Heart of the Third Reich," it was during this return trip that Kolbe came extremely close to dying -– twice. The day before Kolbe was set to depart for Bern he found himself in the midst of a British Royal Air Force bombing attack. One bomb exploded just over 150 feet away from him, knocking both him and local official over and covering them in debris.

The following day, Kolbe was riding on a train between Berlin and Basel when once again the British bombers struck. Upon hearing the "blue alert" that the air force was coming, Kolbe quickly jumped off the train and took cover in a nearby ditch. The bombing damaged the tracks, causing a severe delay for Kolbe, and he was becoming physically sick with fear over being discovered as a double agent.

Yet, Kolbe still made it to Switzerland and had several secret meetings with Dulles and Mayer. They also worked out arrangements for Kolbe to send back more data to Switzerland, through another intermediary, to keep the flow of information coming.

Kolbe's contributions were invaluable

Among the many spies the Allies had in Germany during WWII, Fritz Kolbe is given special recognition by many. Allen Dulles (pictured above), the eventual head of the CIA, took time to specifically mention Kolbe's immense contributions in his book on WWII espionage, "The Secret Surrender." He referred to Kolbe by his codename George Wodd, and called him "our best intelligence source on Germany" and "undoubtedly one of the best secret agents any intelligence service has ever had."

During his time as a double agent, Kolbe provided the Allies with incredible amounts of invaluable information. One of his biggest contributions was the outing of German spy Cicero from the British Embassy. Using cables provided by Kolbe, Dulles was able to notify the British of a potential spy in their ranks, "thus putting Cicero out of business ... the Germans nor Cicero ever knew."

Kolbe provided over 1,600 documents to the Americans from the German Embassy, and at times he was able to do so with incredible speed (per James Srodes in "Allen Dulles: Master of Spies"). He provided valuable information about the Wehrmacht, the German V2 rocket program, and the deteriorating military situation in Japan (per the Boston Globe). While it is hard to directly measure the impact of Kolbe's information, it was certainly invaluable for the Allies in the waning years of the war.

Kolbe continued to spy after the war

After the war, Fritz Kolbe continued to work with the Americans and found himself ostracized amongst his former colleagues in Germany. Per the Boston Globe, Kolbe continued to work for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and their successor the CIA for several years. It is unclear exactly how long he continued to provide Americans with intelligence, as the documents revealing so are classified, but he remained friends with Allen Dulles until the latter's death in 1969.

After the war, Dulles was able to get Kolbe a $10,000 fund from the OSS, mainly to benefit his son in the event of his death. Kolbe tried to get another job in the German civil service under new German President Konrad Adenauer, but had no luck. Instead of being revered as a spy who helped bring down the evil Nazi government, he was derided as a traitor and saboteur and given the cold shoulder.

In 2004, the German government finally officially recognized Kolbe's contributions and honored him with a plaque in the foreign ministry building (via the Independent). He died of gallbladder cancer in 1971, and the CIA had a wreath laid on his casket at the burial, a symbol of his immense work for the U.S. (per "A Spy at the Heart of the Third Reich").