The Untold Truth Of The Underground Abortion Network, The Jane Collective

In the 1960s and '70s, a group of women in Illinois took it upon themselves to help people access safe abortions. Known as the Jane Collective, they started out referring people to doctors who would provide abortions, and before long, they were performing the procedure themselves. In doing so, the Jane Collective helped thousands of women in Illinois access abortion at a time when abortion wasn't a federal right in the United States.

Many people who sought the help of the Jane Collective reported owing their lives to the group, especially because many doctors wouldn't even perform an abortion if the life of the pregnant person was at risk. One woman stated that "if it hadn't been for Jane, I would have died," per Ms. Magazine.

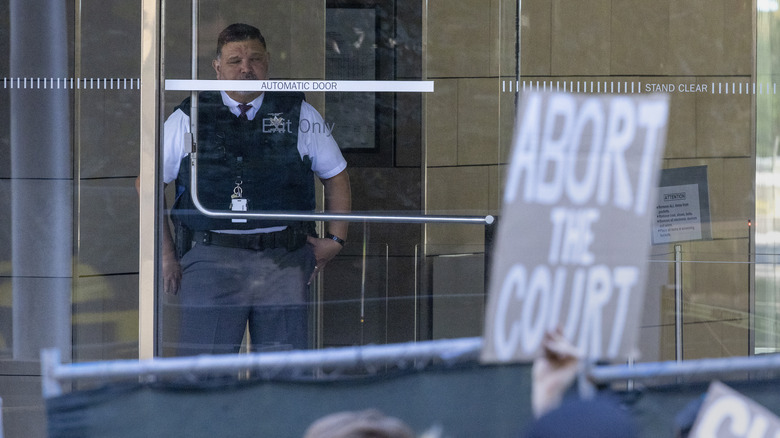

The Jane Collective wasn't unique. Even in the 21st century, organizations like Women on Waves continue to provide safe and accessible reproductive health services to people in countries with restrictive reproductive health laws. And with the overturning of Roe v. Wade in June 2022, groups like Jane are likely to return to the United States. This is the untold truth of the underground abortion network, the Jane Collective.

What was the Jane Collective?

The Jane Collective was an underground organization based in Chicago that provided abortions to people in Illinois in the years before Roe v. Wade legalized abortion for the following half-century. According to The Embryo Project Encyclopedia, the group that would become the Jane Collective began in 1967 to address the fact that abortions in Chicago at the time were unsafe, expensive, and being performed by unqualified people. At that time, most pregnant people in the United States had to resort to back-alley abortionists, and they didn't have the luxury of knowing whether or not the person performing the abortion was competent. Although NPR writes that the introduction of antibiotics in the 1940s decreased the number of deaths from illegal abortions, thousands of women were still admitted to hospitals every year due to complications from illegal abortions.

Before becoming the Jane Collective, the group initially worked with students from the University of Chicago who were seeking abortions. But within two years, the group became a formal referral service known as the Abortion Counseling Service of Women's Liberation. By the time the group was disbanded in the wake of abortion legalization, the collective was performing abortions themselves, writes The Chicago Tribune, with members of the collective ranging from students and housewives to professionals.

The creation of the Jane Collective

The foundation of the Jane Collective was laid in 1965, when Heather Booth, a student at the University of Chicago, was asked to help a friend's sister. The New York Times reports that Booth was told that the woman was pregnant and was desperate to have an abortion. "I was told she was nearly suicidal. I viewed it not as breaking the law but as acting on the Golden Rule. Someone was in anguish, and I tried to help her."

Booth knew Dr. T.R.M. Howard, a Black surgeon and civil rights leader, through her civil rights activism, according to NBC News, and she reached out to him regarding her friend's sister. After Howard performed the abortion, Booth started receiving call after call from other pregnant people who also wanted abortions.

According to Timeline, Booth realized that not only did these people need a referral to a reliable doctor, but they needed information and someone to talk to. She began meeting people in person to talk with them and tell them what she knew about the abortion procedure, but soon she was overwhelmed with calls. Bringing together other women she knew from her activism, they were soon meeting regularly. Initially, they called themselves the Abortion Counseling Service of Women's Liberation. But when they decided that people should ask for "Jane" when they called, they became the Jane Collective.

Jenny's abortion

A woman known as "Jenny" was another founding member of the Jane Collective. According to Timeline, Jenny had Hodgkin's Lymphoma when she learned she was pregnant for the third time in her life. And not only had the previous pregnancy taken such a toll that she feared being pregnant again might kill her, but Jenny also knew that the baby would likely be born with defects due to the radiation in her cancer treatments.

The Embryo Project Encyclopedia writes that because abortions were illegal, the only lawful way for Jenny to end her pregnancy was to get permission from a hospital's therapeutic abortion committee. However, the hospital committee denied her request. After speaking with two more psychiatrists and telling them she would opt for suicide rather than be forced to give birth again, Jenny was finally granted her request for an abortion.

The experience radicalized Jenny, as did the fact that her reproductive health was controlled by a group of men. By 1967, she and Booth had gotten together with other women to create the Abortion Counseling Service of Women's Liberation. Jenny would also insist on being present with people during their abortions in order to make sure they were safe.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 or the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Call Jane

Initially, information about the Jane Collective spread primarily through word-of-mouth. But before long, advertisements were popping up in newspapers and on the subway that read, "Pregnant? Don't Want to Be? Call Jane," writes NPR. When people called the number, they were connected with someone from the Jane Collective who asked them what they could provide the caller with. According to Hey Alma, callers had to specifically ask for an abortion; the goal of Jane wasn't to promote the procedure, but to help women access it safely.

A few days after the initial phone call, a counselor would call the person seeking the abortion for a counseling session to confirm that they wanted an abortion and to explain the procedure. Because information about reproductive health was limited at the time, the Jane Collective was especially concerned with making sure people were fully informed about what was happening to their own bodies. They also tried to make the procedure room as un-medical and comfortable as possible, per KCRW.

If a client could afford to travel, the Jane Collective would refer them to England, where abortions were legal, or places like Mexico or Puerto Rico, where the Jane Collective knew a network of doctors who performed safe abortions. However, traveling abroad wasn't an option for a majority of the people who used the Jane Collective, so they were referred to one of several Chicago physicians who were willing to perform the procedure.

Run-ins with the police

Occasionally, the Jane Collective was confronted by the Chicago police. Timeline writes that police followed a patient at least once, but she was able to notify the collective, "who cleaned up the surgery area and played dumb." Neighbors also informed the collective that their house was being surveilled, and one member had a run-in with a police officer at an anti-war rally who said to her, "Hi, Jane."

But according to NBC News, the police were actually relatively tolerant of the Jane Collective. "Because male authorities — from police to judges — had themselves solicited services for their wives, daughters and mistresses, they were able to operate largely without police interference."

However, the threat of imprisonment still loomed large. The Chicago Tribune writes that one member of the Jane Collective had a husband who reportedly said to her, "You're going to wind up in jail. You'll be a felon." The group was cautious and kept as little documentation as possible in case of a police raid.

Not really a doctor

The Jane Collective initially used a few different doctors, but some of them charged enormous amounts of money or insisted that the person receiving the abortion be blindfolded. The Jane Collective started mainly using just one doctor, often referred to as "Nick" or "Mike," because he didn't seem inexperienced. Timeline writes that Mike also allowed members of the collective to be present during the abortion, so the members of the collective started learning more about how to perform abortions as well.

But in late 1970, Vanity Fair writes that Mike revealed to some of the Jane Collective members that he'd never actually gone to medical school, and that he had learned to perform abortions from a doctor who supposedly worked for the mafia. The Jane Collective was devastated when they found out, because the fact that they were offering illegal abortions from a fake doctor made them look hypocritical. One woman even claimed that the collective was deliberately deceiving people, and some have suggested that up to half of the members left the group as a result.

But one member, Judith Arcana, spoke up and said, "Hey, wait a minute. If he can do this, and we know he's really good, then we can do this."

Member-provided abortions

By 1971, the Jane Collective was performing most of the abortions themselves. And according to Timeline, because they were doing the procedures themselves, they were able to bring down the cost of abortions from around $600 to $100, or whatever people could afford. Upon learning many of the women who used their service weren't receiving any medical care at all, Jane Collective members learned to perform pap smears and arranged for a lab to analyze the results for $4.

Around 20 women from the collective worked up to four days a week and performed roughly 25 abortions a day, according to Vanity Fair. But only about four of the roughly 100 members in total learned how to perform surgical abortions. The New York Times writes that there are no reported deaths related to a Jane Collective abortion. According to a Chicago obstetrician who provided follow-up care to the collective's clients, their safety record was on par with New York's legal clinics.

However, sometimes there were complications. NPR reports that some people ended up in emergency rooms, while others had to undergo hysterectomies. But considering that illegal abortions accounted for at least 17% of all pregnancy/childbirth-related deaths in 1965, the Jane Collective had a comparatively high success rate.

The demographics of the Jane Collective

Once the Jane Collective was able to reduce their prices for abortions, they started receiving more requests from Black women with lower incomes. Before long, the majority of their patients were Black people. However, the members of the Jane Collective were all white and middle-class for most of the collective's lifespan.

Lois Smith was one of the first Black members of the Jane Collective. According to "Abortion Wars," edited by Rickie Solinger, Smith accompanied a friend to get an abortion with the collective, and there she saw that all the workers were white while the clients were predominantly Black. And while she waited for her friend, she started counseling the other Black people who were waiting.

Smith decided to join the Jane Collective to continue counseling Black people seeking abortions. She reportedly reprimanding the collective before joining, saying "You guys are the white angels that are going to save everybody and where are the black women at?" However, Smith's friends warned her about joining the collective, stating that "those white women would get out of it, but not you. You could go to jail," per Timeline.

According to Smith, there were few Black women in the Jane Collective. "We could never develop a critical mass [...] to get together to talk about what we were doing. But we didn't look on it as a Black or white women's issue; women needed termination of pregnancies, and there was unity created by women who were desperate," she said.

'Where's the doctor?'

On May 3, 1972, the police finally went after the Jane Collective. KCRW writes that after one woman scheduled an abortion, her sister-in-law reported it to the police. Chicago police arrived outside an apartment building in two unmarked squad cars. After stopping a woman who had just received an abortion and interrogating her outside the building, according to NSPR, the police raided an apartment being used by the Jane Collective.

According to the Chicago Reader, when police burst into the apartment, they kept asking, "Where are the men? Where's the doctor?" and couldn't understand that there wasn't a man there performing abortions.

Seven members of the Jane Collective were arrested. The New York Times reports that, although the women still had the index cards with people's names and addresses on them when they were taken into the police van, they tore off and ate the portions of the cards with their patients' identifying information to prevent the police from getting their hands on anything.

The Abortion 7

The arrested members of the Jane Collective — Martha Scott, Judy Pildes, Diane Stevens, Jeanne Galatzer-Levy, Abby Pariser, Sheila Smith, and Madeline Schwenk — became known as the Abortion 7. Democracy Now! reports that each woman was charged with 11 counts of abortion or conspiracy to commit abortion, and with the possibility of 10 years for each count, each woman faced a maximum prison sentence of 110 years.

According to the Chicago Women's Liberation Union, none of the Abortion 7 would speak with the police. And when they hired their attorney, Joanne Wolfson, she told them "You're the best clients I ever had, people talk to the police all the time and you guys didn't, I love you." The Jewish Women's Archive reports that other Chicago women's organizations also started a fund to help cover the Abortion 7's legal fees.

Wolfson already knew that the Supreme Court was going to rule on Roe v. Wade, so she decided to delay the case as much as possible until the Roe v. Wade ruling came in. According to Wolfson, "nobody wants to prosecute you knowing that this is happening. They don't wanna waste the money, so they're gonna allow us to wait." On January 22, 1973, the Supreme Court issued a 7–2 ruling in Roe v. Wade that effectively legalized abortion across the United States. And after the Supreme Court legalized abortion, the state of Illinois dropped all charges against the Abortion 7.

Jane Collective's legacy

In its seven-year lifetime, the Jane Collective organized and performed thousands of abortions. According to NPR, the group was responsible for around 11,000 first- and second-trimester abortions. At its peak, it was serving 10 people a day, four days a week.

After abortion was legalized, the Jane Collective was disbanded, since it was assumed that their abortion services would no longer be necessary. Vanity Fair writes that Jane Collective members Laura Kaplan and Eileen Smith took the remaining documentation and contact box that listed people's information, and, according to Kaplan, "we read the names to each other, and then tossed the cards one by one into the fire. We thought, 'this is none of anybody's business.'"

However, the battle for reproductive rights didn't end with the Roe v. Wade ruling. In 1992, the Supreme Court overturned the trimester framework. This is considered to be one of the earliest returns to abortion restrictions, according to "The Changing Voice of the Anti-Abortion Movement" by Paul Saurette and Kelly Gordon. Abortion restrictions continued to increase across the United States, and on June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade with its ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization. With this decision, the Supreme Court ruled that abortion is no longer a federal constitutional right. And as a result, underground organizations like the Jane Collective are more than likely to pop up again once more as people across the United States try to access abortions.