What We Know About The Jewish Custom Of Kaparot

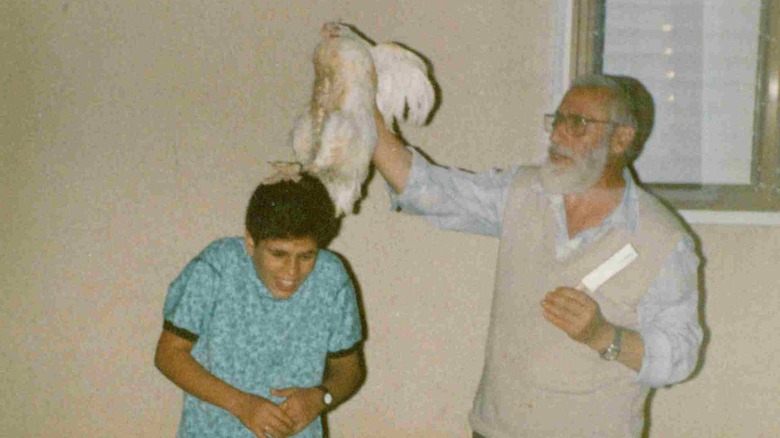

The holiest day on the Jewish calendar is Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, which is focused on repentance and atonement for sin, usually represented in a physical way by fasting and intensive prayer. As the Rabbi Dr. Reuven Hammer explains on My Jewish Learning, however, over the centuries, various folk customs have arisen among different Jewish communities to help further emphasize the ritual purity that is at the center of Yom Kippur, ranging from cleansing oneself in a special bath called a mikvah to the thankfully out of fashion practice of whipping oneself. But one of the more infamous and controversial ritual folk customs leading up to Yom Kippur is kaparot, the practice of swinging a chicken over someone's head for the remission of sin, still performed in some Jewish communities, usually Orthodox ones.

The word kaparot — also spelled kapparot, kaporos, and a suite of other transliterations — is Hebrew for "atonements" (in the sense of paying off a ransom) and has the same root as the "Kippur" part of Yom Kippur. The basics of the ceremony are this: a person looking for atonement buys a chicken, the chicken is waved over their head three times while they recite a short prayer three times, and then the chicken is slaughtered according to Jewish dietary laws and donated to charity for the pre-Yom Kippur meal. If a chicken is not available, other kosher birds or the cash equivalent of a chicken may be used and donated in its place.

When and how to perform kaparot

As Chabad explains, kaparot is usually performed at a designated place within the community, which usually has prepared chickens available for purchase, as well as having their own shochet, which is an expert kosher butcher, on hand to make sure the chickens are slaughtered correctly and humanely. While kaparot can be performed any time between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur (the first 10 days of the month of Tishrei on the Hebrew calendar, usually in September or October on the Gregorian calendar), it is typically done the night before Yom Kippur.

Typically, a man will use a rooster for the ritual while a woman will use a hen, though a chicken can be shared if buying multiple birds is too expensive. A pregnant woman should use three chickens: a hen for herself, and a rooster and a hen if the gender of the baby is unknown. (Chabad has no information on what to do if a non-binary person wants to perform kaparot.)

Short passages from the books of Psalms and Job regarding the redemption of sin (which you can find on My Jewish Learning) are read and a short prayer said as the chicken is waved over the head of the person seeking expiation, and this is repeated three times, so that the chicken passes overhead a total of nine times. The chicken is then brought to the shochet to be slaughtered and a blessing is said over the bird's blood. It is customary, Chabad says, to tip the shochet.

The reason for chickens

According to Chabad, the practice of kaparot began in the medieval period, with the earliest written mention popping up in the A.D. 600s (though the reference is written in a way to suggest the ritual was already well known). Chabad suggests a number of possible reasons for the use of chickens. A widespread explanation is that the Aramaic word for rooster is the same as the Hebrew word for man, so the substitution of chicken for person is a kind of metaphysical bilingual pun. Additionally, chickens are relatively easy to find and cheap to acquire, but also importantly, they are not among the birds — such as pigeons and doves — that could be offered as sacrifices at the Temple, helping to make clear that this practice is not an offering to God, but rather, as Chabad claims, a symbolic reminder to oneself of the price of sin. For this reason, it is important to pick a white, or mostly white, chicken to represent the purity following the redemption of sins. If a white chicken isn't possible, by no means should a black chicken be used, as black represents God's punishment.

Rabbi Hammer points out on My Jewish Learning, however, that the slaughtering of a chicken even as a metaphorical substitute for a person reflects the pattern of scapegoating, an ancient practice in which a goat loaded up with a community's sins was sent out into the desert for the mysterious figure of Azazel.

Objections and controversies

While kaparot is still practiced among some Jewish communities today, it's probably not surprising to learn that it's a controversial ritual that is by no means universal among Jews, and it has in fact been condemned by some rabbis since essentially as soon as it started. Rabbi Hammer explains that notable rabbis such Moses ben Nahman in the 13th century (also known as Nachmanades or the Ramban) and Rabbi Joseph Karo in the 16th century both objected to the ceremony, likening it to superstition and saying that it too closely resembled pagan practices to be an acceptable Jewish practice.

Chabad, however, argues that kaparot is such a long-standing and time-honored tradition that it is commonly practiced among many communities, including Sephardic Jews, who typically follow the teachings of Rabbi Karo closely. Furthermore, they argue that the objections of notable rabbis were really about the ceremony being performed incorrectly, or about the proceeds not being donated to charity as they were supposed to be.

Likewise, Chabad insists that the practice of kaparot must be celebrated with humanity and kindness to the animals involved, without causing them pain during the swinging portion of the ceremony, both because God commands humans not to inflict unnecessary pain, and because it would render the birds non-kosher. It is especially essential, they argue, to treat a fellow creature of God with kindness on the eve of Yom Kippur, the day in which Jewish people as humans ask God for his kindness and mercy.