Times Popes Have Apologized For The Actions Of The Catholic Church

It's no secret that organized religion — of all kinds — has caused a huge number of problems throughout history. The Catholic Church has been one of the biggest — religions and sources of problems — and for much of the church's existence, they've thought themselves to be pretty blame-free. Jeremy Bergen is a professor of religious and theological studies at Ontario's Conrad Grebel University College. He has a specialty in church apologies, and in 2022, he told The Washington Post: "For 1,900 years, churches didn't apologize for the bad things they did."

That started to change in the aftermath of World War II, Bergen says. Other religious leaders started to realize that they had failed millions of Jews by either sitting back and doing nothing or — in the case of the Vatican — actively helping Nazis escape Europe and justice. The Protestant church of Germany was the first to issue an official apology. It kicked off an era where high-ranking church officials were expected to at least acknowledge when bad things happened in the church's name.

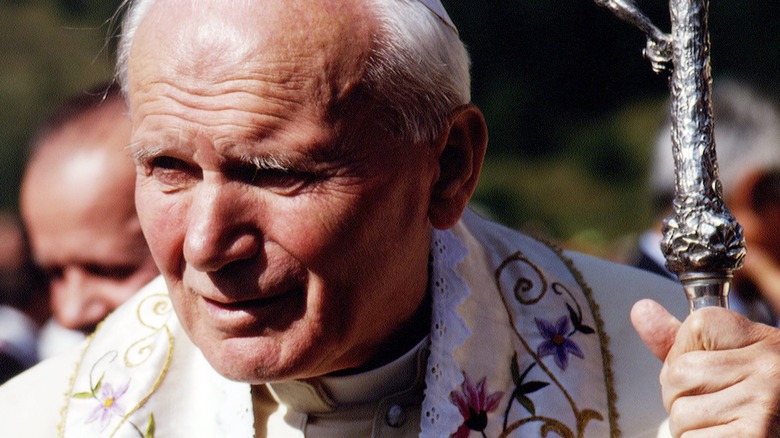

Since then, popes like John Paul II, Benedict, and Francis have apologized for some of the Catholic Church's most horrific actions. Some say it's a start, some say it's too little, too late, and others say that it's great, sure, but actions speak louder than words. When it comes to these heinous deeds, is "Sorry!" enough?

An apology for the mistreatment of Canada's indigenous peoples

In 2022, Pope Francis made headlines when he headed to Canada on what the CBC called a "penitential pilgrimage." His first stop was at one of the many residential homes across the country, and along with some prayers, services, and blessings, Pope Francis apologized — a lot — saying, "I humbly beg forgiveness for the evil committed by so many Christians against the Indigenous peoples." There was a lot to forgive, and according to many — including the Canadian government, says NPR — the apology was nowhere near enough.

To understand why, it's necessary to get into some pretty dark stuff. In the 19th century, the church started a campaign to Christianize Indigenous Canadians. It was based on 15th-century beliefs in colonial Europe's destiny to spread their religion, which meant removing children from their homes to enroll them in church-run schools. There, they quickly found an environment where sexual abuse was widespread, and punishment — for transgressions like speaking a native language — involved beatings.

The last of the schools only closed in 1998, and according to CNN, some of the 150,000 children came forward to say that the apology triggered years of trauma they had been living with for decades. Around 4,000 children died in school custody — 215 were found buried on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School, and the government is still searching for more, in hopes of finally allowing families some closure.

An apology to the women and children of Ireland's Magdalene laundries

According to the BBC, it was 2015 when the world learned that more than 800 babies were buried in a mass, unmarked grave on the site of a Catholic-run mother-and-baby home in Tuam, Co. Galway. The former workhouse was converted into a facility for housing unwed, pregnant women and their children in 1925, and was active until 1961. Historian Catherine Corliss compiled a list of 798 names of the children who died at the home.

That wasn't the only one, either: History says that dozens of laundries lasted for 231 years, and were thought to have housed somewhere around 300,000 women. Many were referred to by numbers instead of names, and were forced to work from sunrise to sunset to pay off their debt to the church — for the sins that included flirting, mental illness, and getting pregnant out of wedlock (including cases of sexual assasult). Most had their heads shaved, survived on bread and water, and were locked in solitary confinement when not working.

The last laundry closed in 1996, and when Pope Francis visited Ireland in 2018, he apologized for abuses that included the mother-and-baby homes. He met with some of the survivors, and although he was pretty clear how he felt about it on a personal level — calling cover-ups "like dirt in a toilet, filth," the Irish Examiner says that without zero-tolerance policies for abuse put in place going forward, the apology felt hollow.

Kind of apologizing to the LGBTQ+ community

The Catholic Church has taken a notoriously intolerant view of the LGBTQ+ community, even with those who choose to work with that community. In 1999, Father Robert Nugent and Sister Jeannine Gramick were publicly condemned by the church for teaching theology and workshops developed with LGBTQ+ topics in mind. After two decades of scrutiny, it was determined that they had "harmed the community of the Church." The Washington Post says that they broke away and founded their own ministry to continue doing what they were doing, and when she received a letter of apology from Pope Francis in 2022, it was a big deal.

That came six years after what was sort of an apology to the community — enough that the BBC says it had conservative Catholics all in a tizzy. Pope Francis was returning from a trip to Armenia when he told the media, "I think that the Church should not only apologize... to a gay person whom it has offended, but it must apologize to the poor as well, to the women who have been exploited, to the children who have been exploited... It must apologize for having blessed so many weapons."

While some called it a "groundbreaking moment," (via CNN), there's a footnote. While the pope called for an end to discrimination, his reason wasn't great: "The problem is a person that has a condition, that has good will, and who seeks God, who are we to judge?"

Former Pope Benedict's apology for the ongoing sexual abuse of minors

Is it possible that an apology for that could make things worse? It turns out that the answer is yes, and the not-really-an-apology came from Former Pope Benedict in 2022. Benedict — who resigned in 2013 — had been accused of overlooking sexual abuse while he was still known as Joseph Ratzinger, an archbishop of Munich. According to Politico, there were 497 children and teenagers identified as the victims of sexual assault in the Archdiocese of Munich alone, in the 74-year period leading up to 2019. Ratzinger had long claimed to have been unaware of the abuses linked to a particular priest. After it came out that he had been present at a meeting to discuss that exact thing, it put his whole plausible deniability thing in doubt.

Benedict's apology read, "I can only express to all the victims of sexual abuse my profound shame, my deep sorrow and my heartfelt request for forgiveness. I have had great responsibilities in the Catholic Church. All the greater is my pain for the abuses and the error that occurred in those different places during the time of my mandate." As NPR points out, that's a carefully crafted sentiment that apologizes without shouldering blame.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Pope Francis' apology for the ongoing sexual abuse of minors

The numbers are staggering: In 2022, The Star reported that independent inquiries have found more than 216,000 people who have been victims of sexual assault perpetrated by the French Catholic clergy in the 70 years leading up to 2020. In 2019, an estimated 1,700 Roman Catholic priests were both identified by the church as "credibly accused of child sexual abuse," and were still living and working with children.

In 2018, headlines of an abuse case that spanned parishes across Pennsylvania horrified the world: More than 1,000 victims had been sexually assaulted by priests for years, and a 1,365-page report from a grand jury put the spotlight on all the horrors. In response, Pope Francis issued a formal apology saying, partly (via NBC News): "With shame and repentance, we acknowledge as an ecclesial community that we were not where we should have been... We showed no care for the little ones; we abandoned them." The following year, The Guardian reported that he had done something about it and gotten rid of the so-called "pontifical secrecy" that had protected so many, along with putting in other practices that made it an offense to try to silence victims.

If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services.

An apology for the execution of Jan Hus

Jan Hus isn't exactly a household name in many countries, so here's a quick history lesson. He's generally thought of as the father of the Czech nation. He's sort of a cross between George Washington and Martin Luther, and it's that second one that ended up getting him in major trouble with the Catholic Church, according to the National Catholic Register. He very vocally suggested all kinds of ways to make the Catholic religion better, including heretical things like making the Bible available in the Czech language, and making it clear that the church was the sum of all parts, not just the important higher-ups. In 1415, he was brought up on charges of heresy, found guilty, and burned at the stake.

Relations between the Catholic Church and the Czech people have been best described as "frosty" for more than 600 years because of it. In 1999, Pope John Paul II said he felt "the need to express a profound regret for the cruel death inflicted on Jan Hus and the consequent wound (via Catholic Culture)."

The pope called for the incident to be turned into something of a learning experience, and in 2015, Pope Francis issued another apology at a reconciliation ceremony at the Vatican. Radio Prague International reported that the pope had said that the church needed to ask forgiveness for the act, because it had done nothing but hurt everyone involved on both sides.

An apology for abuse ... and not believing the victims

In 2002, members of a parish in Santiago, Chile, came forward to accuse Rev. Fernando Karadima of sexual assault. It would take another eight years for the accusations to go anywhere: According to The Guardian, that's when they went so public that the Vatican had no choice but to investigate.

Meanwhile, victims pointed the finger elsewhere, at Bishop Juan Barros. He was accused of helping to cover the whole thing up — by the time the case went before a judge, it was dismissed not for lack of evidence, but because of the amount of time that had passed. Pope Francis' response to the accusations of a cover-up was less than stellar, and he called it "all calumny," or slander. A few days later, The Guardian reported that he issued a not-really apology, saying that while he knew he could have chosen his words better and he was sorry ... but anyone throwing accusations at Barros without concrete evidence was committing slander.

Fast forward from January to April, and the release of the 2,300-page report, and Pope Francis was once again apologizing — and inviting victims to the Vatican to deliver the apology in person, says The Washington Post. Barros continued to deny involvement and handed in his resignation in June of the same year (via NPR).

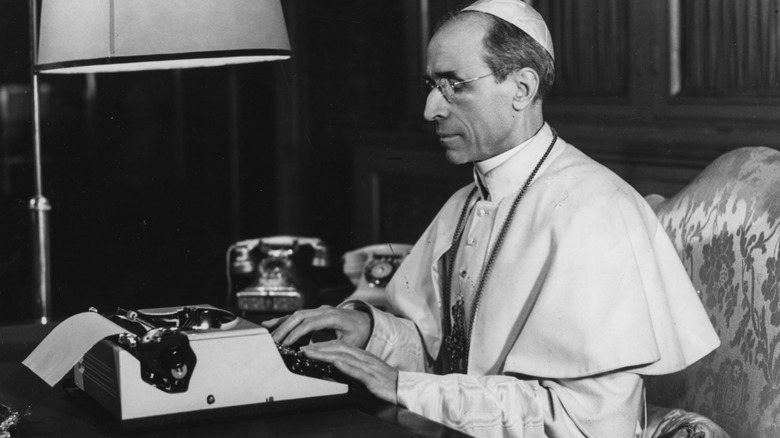

An apology for not challenging the Nazis

Any conversation about questionable popes should probably start with Pius XII (pictured), who held the office during World War II. The church's stance on the war and the Holocaust wasn't great, and according to The New York Times, Pope John Paul II first mentioned a formal apology in 1987. It wouldn't happen for another 10 years, and when it did, it left many people wondering why they'd bothered waiting for so long. The pope and the Vatican issued a document called "We Remember: A Reflection on the Shoah," and in it, The Washington Post reports that it contained sentiments like, "We deeply regret the errors and failure of those sons and daughters of the church."

The consensus among Jewish leaders was that things were headed in the right direction, but it wasn't nearly enough. Some — like Efraim Zuroff of the Simon Wiesenthal Center — pointed out that one of the things they hadn't taken responsibility for was the historical persecution of the Jews that had opened the door for the whole thing in the first place.

And then, there was the matter of Pope Pius XII. The Vatican was reluctant to condemn him. At the same time, Jewish leaders pointed out the damage that his silence had caused. Things didn't improve much: In 2009, CNN reported that Pope Benedict had to issue a very fast apology after issuing a decree lauding the World War II-era Pius XII for his "heroic virtues."

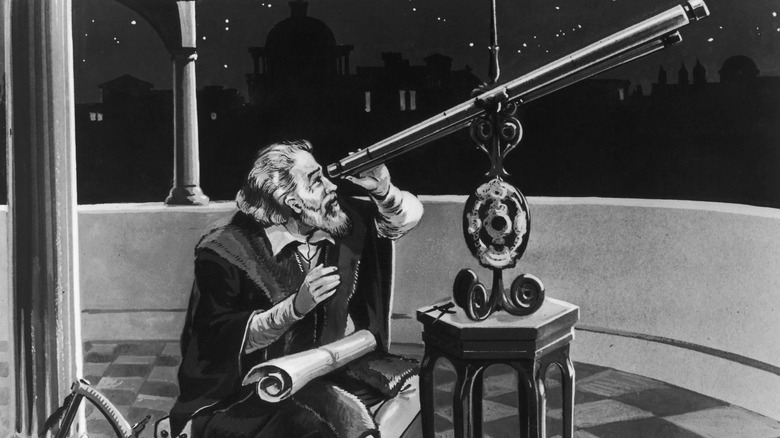

An apology for the condemnation of Galileo

It's one of the most famous episodes in scientific history: Galileo discovered that the Earth revolved around the sun and wasn't the center of the universe, the Church put him on trial for heresy, and he was only able to save his life by recanting.

The New York Times says that over the years, the Vatican has very quietly and discreetly backpedaled, by doing things like removing Galileo's works from their banned books list. Then, in 1992, Pope John Paul II spoke at the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, where the Associated Press says he gave the final word on the matter.

He said that his predecessors had made their mistake by applying the "literal sense of sacred scripture" to the natural world around us. He went on to say that there were two separate areas of knowledge — scriptural and "one which reason can discover by its own power" — and the truth of one didn't necessarily negate the truth of the other. He continued (via The Washington Post): "The clarifications furnished by recent historical studies enable us to state that this sad misunderstanding now belongs to the past." With that, Galileo was no longer on the church's hit list.

An apology for the church's role in the slave trade

New York Times journalist Rachel L. Swarns did a deep dive into the history of slave-owning Jesuits in America and found some pretty shocking stuff — including the fact that not only did early Jesuits own hundreds of slaves, but the profits made off those slaves were used to both grow the church's influence in 18th century America, and to finance schools like Georgetown University. The story of Noah and his sons was famously used to justify slavery, and for a long time, the church was just totally fine with that.

Pope John Paul II (pictured) apologized for that in 1992, when he held Mass on the island of Sao Tome e Principe — once used as a stopover point on the Atlantic slave trade routes. That apology, says the Associated Press, was one of a number he's made for the role of the church in the slave trade: "I cannot but deplore this cruel and sad offense to the dignity of the African man," he was quoted as saying.

The New York Times reported on similar comments made back in 1985, when — on a trip across Africa and at a stop in Cameroon — the pope asked for forgiveness and for the world to move on with compassion: "In the course of history, men belonging to Christian nations did not always do this, and we ask pardon from our African brothers who suffered so much because of the trade in Blacks."

An apology for discrimination against women

In 1995, The Washington Post reported on an open letter written by Pope John Paul II, with the apparent goal of apologizing to the world's women for the discrimination they had faced from the Catholic Church. It really didn't go as it was probably planned, on either side.

While the pope lauded things like the advances made in civil rights, getting equal pay for equal work, and women's rights in the workplace, he still made it very clear that Jesus had chosen all male disciples, so there was still no place for female priests. He also condemned abortion — even after sexual assault — as a sin. He did say, though: "Women's dignity has often been unacknowledged and their prerogatives misrepresented. And if objective blame, especially in particular historical contexts, has belonged to not just a few members of the church, for this I am truly sorry."

What he was referring to was the church's longtime refusal to allow women to participate in Mass by performing non-priestly duties — but as far as an apology for the church's treatment of women beyond that, it was a bit lacking. Some — like representatives from the group Catholics for a Free Choice, called it "only rhetoric," and noted that until policies were actually changed, it wasn't going to be clear that the apology was meant wholeheartedly.

An apology for the 11th-century sacking of Constantinople

World History says Pope Innocent III kicked off the Fourth Crusade in 1202, and the idea was that Rome was going to take Jerusalem back from Saladin. That didn't happen — what happened instead was that Roman Crusaders sacked, pillaged, and burned Constantinople. The city was also Christian, and the reason for the sacking was "mistrust." If that doesn't sum up a heck of a lot of global conflicts, nothing does.

As a result of the brutal sacking, the next 1,000 years were marked by a deep schism between Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy. When Pope John Paul II announced he was going to a visit in 2001, the mood was summed up by one Greek Orthodox priest who came carrying black balloons, saying (via the Irish Independent), "I am in mourning. For me, the Pope is the root of all evil."

It was the first time a pope had visited Greece since 1054, and according to the Los Angeles Times, it was reportedly one of his final wishes to spearhead the reconciliation between the two groups. His sentiments included a plea that "sons and daughters of the Catholic Church [who] have sinned by action or omission against their Orthodox brothers and sisters, may the Lord grant us the forgiveness we beg of him." Orthodox leader Greek Archbishop Christodoulos ended by saying that although there was plenty still to be worked out, "The pope was very nice to us," and they shared a hug and a walk side-by-side.