Disturbing Details Found In John Wilkes Booth's Autopsy

While enrolled in a course called "Civil War and Medicine," sophomore Acadia Parker of Binghamton University began research for her final project on Civil War-era autopsies (via BingUNews). The greenhorn historian paid a visit to the National Archives Research Center and began thumbing through authentic Civil War autopsy reports alphabetically. Far from the digital scrolling of modern research, Parker was able to appreciate how these original documents carried visceral characteristics, describing that "they smell like old tobacco and they have bloodstains on them."

With barely a semester of historical research experience, Parker started with A and soon found herself under "Assassinations." Before she realized, there in her hand was John Wilkes Booth's autopsy report, followed shortly by Abraham Lincoln's.

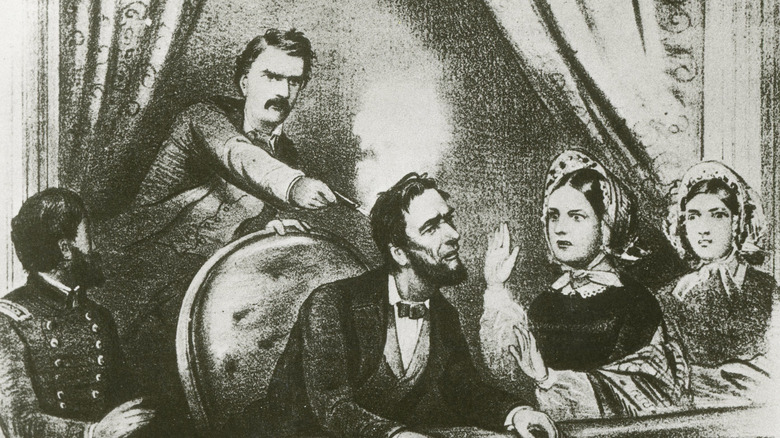

Civil War-era autopsies usually contain a couple of lines describing the events leading to death. Parker found 19th century doctors wrote about Booth's death with the same medical analysis and language used today. While medical documentation is usually dry, the pain of a heartbroken nation seemed to seep in around the edges of the autopsy written by Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes. The emotionally charged text and the events surrounding this particular autopsy are both intriguing and disturbing.

Moving the body

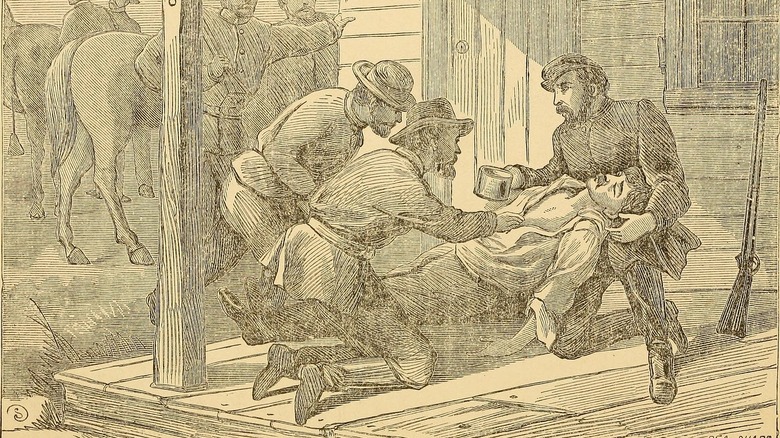

Traveling after the Civil War wasn't a straightforward event, even for an assassin's corpse. Around sunrise on April 26, 1865, Booth was tracked down to a large Virginia tobacco barn. He was fleeing under the alias James W. Boyd. After refusing to exit, the barn was set ablaze by an overzealous tracker. But before he could escape the inferno, Booth suffered a gunshot wound which would lead to his death (via Navy Medicine, posted by Indiana State University). After he died, Booth's body was wrapped in a horse blanket and transferred from a market wagon, to a steamer ship, a government tugboat, and finally onto an ironclad, the U.S.S. Montauk, docked in the Washington Navy Yard (via Roger J Norton).

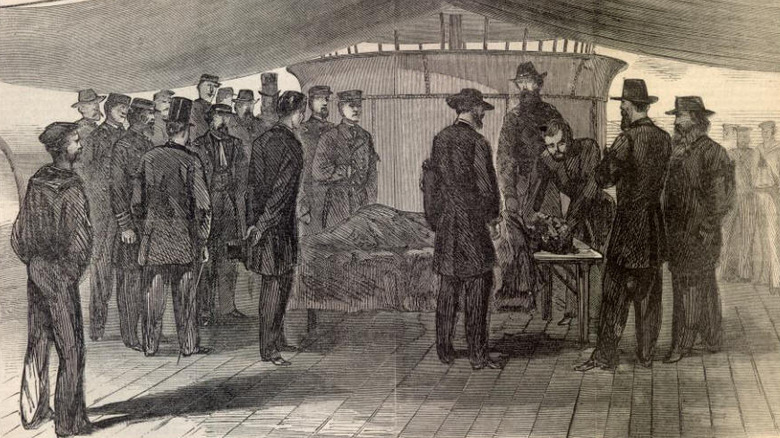

Arriving sometime around 1 a.m. or 3 a.m. on April 27, Booth's body was placed on a makeshift carpenter's bench next to a rotatable gun turret. The horse blanket that covered the body was removed and replaced with a tarpaulin. It was going to be an unusually hot day for April, the metal siding of the boat likely growing warm to the touch as the body awaited examination.

An autopsy of a president's assassin

Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes arrived at the Montauk in the late morning of April 27, 1865. Just two weeks prior, he had directed President Abraham Lincoln's autopsy (via Smithsonian Institution). Now, Barnes was to be one of the three surgeons to perform an autopsy on the man who assassinated the president. Barnes side-stepped proper military etiquette, boarding the ship without announcement to or acknowledgment of the officers. After this breach of protocol, Barnes "walks up to the corpse and commences to cut adrift the wrappings," said Lieutenant-Commander E.E. Stone (via Naval History and Heritage Command). The autopsy began unceremoniously.

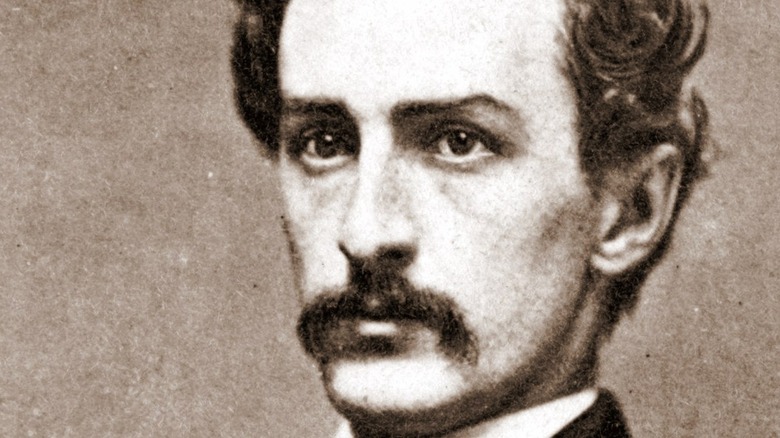

The body was that of a haggard man, with a shaved mustache, a fractured and reset leg, and a large wound in the neck (via Indiana State University). Doctors concluded the cause of death was a conoidal pistol ball that ripped through Booth's neck. The ball struck low, "passing through the bony bridge of fourth and fifth cervical vertebrae — severing the spinal chord (sic)," Barnes described in a report to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

Barnes went on to say, "paralysis of the entire body was immediate." In a remarkably impassioned line for a medical report, the surgeon asserted that "all the horrors of consciousness of suffering and death must have been present to the assassin during the two hours he lingered" (per The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion). Though the physicians weren't present in Booth's last moments, they were able to accurately describe them.

Any last words?

With the second and third cervical nerves intact, Booth likely could still feel his face and head as he died (via Cleveland Clinic). Because the fourth cervical vertebrae contains nerves leading to the diaphragm (via Spinal Cord), one might conclude that Booth asphyxiated, unable to take a breath. However, the extent of the damage likely delayed this process. The presiding Dr. Joseph Janvier Woodward concluded as much, observing that the damage to the phrenic nerve made swallowing "impracticable ... Death, from asphyxia, took place about two hours after the reception of the injury" (via Journal of Community Health).

Many last words have been attributed to Booth, though the autopsy doctors were not confident that he was able to speak after his mortal injury. According to army lieutenant Edward P. Doherty's report on Booth's capture, Booth survived two hours after being shot and no last words were recorded (via The Report of Lieut. Edward P. Doherty).

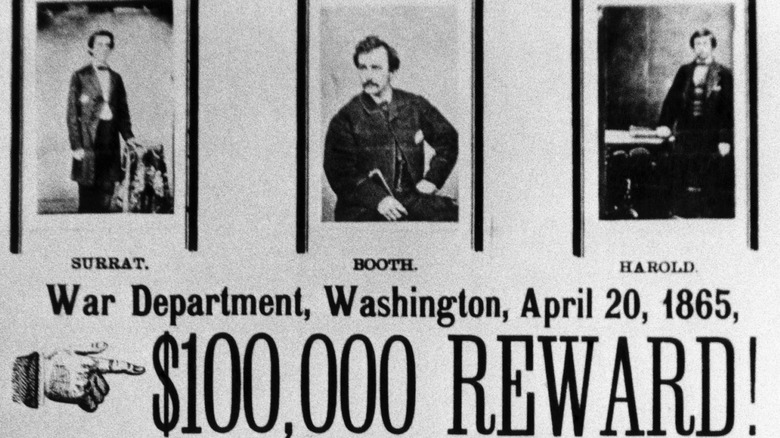

Identification of Booth

According to official records, there were only three civilians on the Montauk around the time of the autopsy and one of them was a young hotel clerk named Charles Dawson (via Indiana State University). The military officers had the clerk identify the body (via Indiana State University). Booth was a regular at the National Hotel, staying whenever he toured through D.C. (via Clio). As Booth signed the register, Dawson recalled seeing a small tattoo on the guest's hand. Dawson had chided Booth, saying, "what a fool you were to disfigure that pretty hand in such a way" (per The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography).

During the Civil War, tattooing your initials on yourself became a bona fide trend, allowing soldiers to rest in peace knowing their body would be identified and sent home using new post-mortem formaldehyde techniques (via Atlas Obscura). The hotel clerk remembered the India ink letters J.W.B., but was inconsistent in remembering their location on the body (via Indiana State University). These were the same initials of the alias Booth used after the assassination.

The rest of the witnesses were conveniently military officers on the ship, who happened to have intimate knowledge of the general appearance of the actor. Though there were numerous witnesses and acquaintances of Booth in Washington D.C., and an unconfirmed rumor that a number of co-conspirators were being held in the hull of the Montauk, none of Booth's local stage coworkers or family were contacted.

The mark that labeled an assassin

Dr. John Frederick May was working in Washington D.C. when he was summoned to the Montauk (via "Mark of the Scalpel," published in Records of the Columbia Historical Society). Convinced he was more needed tending to the living than the dead, he delayed. Little did he know he was being called upon to identify the president's assassin. A more forceful summons arrived and May obeyed when he was reminded of the Latin adage "inter arma enim silent leges" – "for among arms, the laws are silent." His identification of Booth became the most convincing to skeptics.

Dr. May had earlier treated Booth surgically, removing a fibroid tumor from the neck of the future assassin. The wound reopened during the course of one of Booth's performances and Dr. May further treated it, but it left a unique scar.

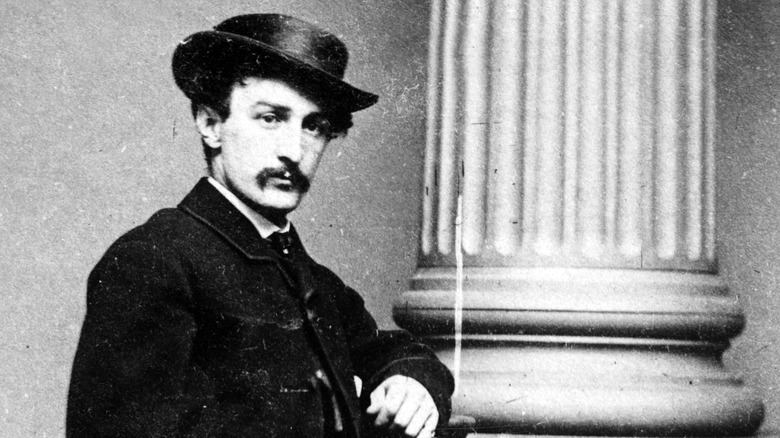

In his memoirs, Dr. May recalled his hesitancy to identify the body. He described seeing "no resemblance in that corpse to Booth, nor can I believe it to be that of him" (per Records of the Columbia Historical Society). Booth's spent remains were a far cry from the once handsome stage performer (via the New York Daily News). It showed evidence of what the toll killing the president and fleeing for 12 days by horse, boat, and foot can take on a body. It wasn't until Booth was turned over that the evidence May needed was clear: the scar from the earlier surgery. "My mark was unmistakably found by me upon it," he confirmed.

Disturbing and mysteriously missing evidence

The body of Booth was buried and re-buried a number of times before it was released back to the Booth family (via Roger J. Norton) though missing some noticeable elements. In what was most likely a lengthy and challenging dissection for the young doctor, Joseph Woodward removed the cervical vertebrae and spinal cord where the bullet had passed. He then wrapped the fourth and fifth vertebrae in cloth and sent them to the newly established Army Medical Museum, never to be reunited with the rest of the body. They remain in the collection to this day at what is now called the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered a single photograph be taken of the corpse (via Smithsonian) by the non-military photographer Alexander Gardner and his assistant (via Indiana State University). After taking the photo, the assistant was escorted by the government detective James A. Wardell, to have the print developed and delivered to the War Department.

Wardell handed the print to the chief of the secret service, Colonel Baker. "I gave him the plate and print," said Wardell, "and he stepped to one side and pulled it from the envelope. He looked at it and then dismissed me." Since that day, no one has confirmed the location or has claimed to have seen the picture, fueling conspiracy theories that Booth had survived (via "The Ghosts of Fredericksburg — and Nearby Environs").

A foretelling aside

Booth was both charismatic and drop-dead gorgeous earlier in life (via New York Daily News), yet his tragic decisions led his visage to be nearly unrecognizable. While the time pre- and post-mortem had taken its toll on Booth's body, "the mark made by the scalpel during life remained indelible in death, and settled beyond all question at the time, and all cavil in the future, the identity of the man who had assassinated the President" claimed Dr. May.

In lighter days, Booth chatted with his surgeon, making jokes before his fibroid surgery. Failing to see the humor in one of Booth's dramatic exaggerations, Dr. May still recorded it in his memoirs. Booth cheekily requested that if ever asked about the surgical operation, the doctor should explain it away by saying "that it was for the removal of a bullet from his neck" (per Records of the Columbia Historical Society).