The True Story Of The World's Most Obsessive Book Collector

With the advent of the ebook in the early 21st century, there's been no shortage of discussion about whether digital media will eventually replace printed books. Surprisingly though, while e-readers may be new, this kind of discourse is not. According to the American Historical Association, the anglophone world has regularly regurgitated its concerns about the "death of the book" since the 1820s.

Despite the arguments, printed books show no signs of disappearing from the post-digital world, with modern bibliophiles seemingly being no less passionate about paper and ink. Readers proudly show off their book collections on social media, and sites like Reedsy are still writing guides about how to get started on #bookstagram, while bookstores like Barnes & Noble are promoting titles popular on #BookTok. Book collections were being compiled long before people were posting "shelfies," however, and arguably the greatest collector ever was Sir Thomas Phillipps.

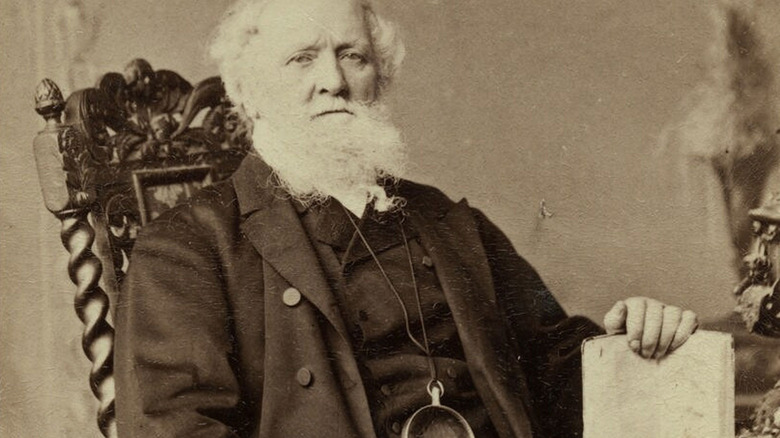

As the Online Archive of California notes, Phillipps was not just an English antiquarian and collector of books; he was a true bibliomaniac, amassing the largest collection of books and manuscripts of the 19th century, and quite possibly the largest private collection the world has ever seen. The book, "A Gentle Madness," all about passionate bibliophiles, describes Phillipps as the greatest collector of manuscripts the world has ever known. While many modern book enthusiasts may take inspiration from his passion, hopefully, they can avoid his deep unpopularity and terrible habit of running himself into debt for the sake of his collection.

The early origins of an obsession

Sir Thomas Phillipps' enthusiasm for collecting books began at a young age, with its origins in the early 19th century and a collection of chapbooks known as Gothic bluebooks. While Phillipps would go on to collect an astonishing amount of rare and treasured literature, chapbooks were a humble place for him to start. As MIT explains, these were (and still are) small books or pamphlets, mass-produced and sold by street vendors. Cheaply printed and typically full of poetry and short stories, chapbooks were easily available and inexpensive, sold for mere pennies. For centuries, chapbooks found popularity as a way of making writing accessible to society's poorest, and, being so cheap to buy, they were also popular with children. Children like the young Thomas Phillipps.

The Grolier Club explains that the earliest of Phillipps' book catalogs may have been started when he was just twelve years old, including chapbooks that had only recently been published at the time. When he wrote his first list, he already had 127 titles. As a dedicated collector, keeping a catalog is an essential habit, and this early listing was the precursor to a habit that Phillipps would keep for the rest of his life. As the Grolier Club Gazette mentions, he later kept a series of almanacs that give a steady record of all his literary activities.

Bibliomania

The compulsive need to buy books is known as bibliomania, and it's quite a well-known trait. As an article in The Guardian will attest, self-professed bibliomaniacs freely make jokes about the eccentricity of their habits. As a hobby, of sorts, book collecting first started to gain extensive popularity among the wealthier citizens of 19th century Britain, and has a long and unusual history all of its own. Even at the time, there were plenty of people in society who viewed this as a peculiar and irrational pastime. To Sir Thomas Phillipps, however, his passion was anything but. He had a purpose.

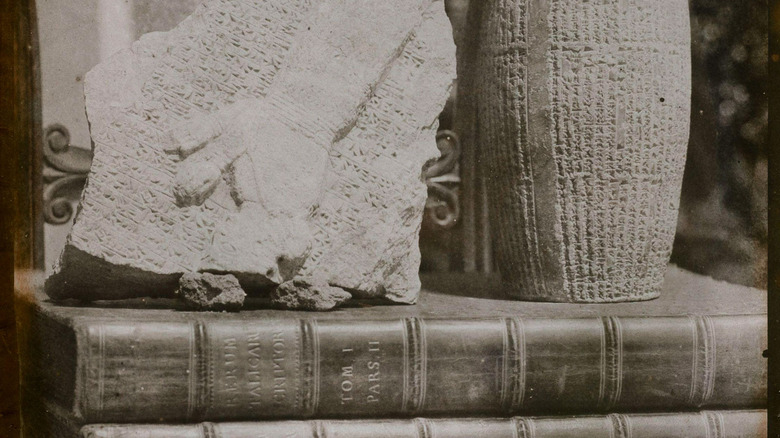

In a time of burgeoning discussions about the allegedly imperiled future of books, while private book collections were springing up, Phillipps had one main goal in mind. Preservation. According to the book "A Gentle Madness," he was saddened to hear about the destruction of old medieval manuscripts written on vellum. Many old documents were written not on paper but on parchment, which, according to the U.S. National Archives, is closer to leather than paper. Parchment was made from animal skins, and vellum was among the finest varieties of it. Typically, parchment was used for the most important documents, which included illuminated manuscripts from medieval times – and also included the original United States Constitution. With these manuscripts being his true passion, Phillipps even coined a word for his style of collecting. Where book collectors are bibliomaniacs, he referred to himself as a "vello-maniac."

Lost literature

Sir Thomas Phillipps' concerns about the destruction of medieval texts were not unfounded. Over time, many have been lost, and, as Smithsonian Magazine explains, only around 9% of manuscripts from medieval Europe still exist today. According to Medievalists.net, there have been a variety of reasons for these old writings being destroyed, either accidentally or on purpose. Fires are historically the biggest hazard, having resulted in entire libraries being lost. Other manuscripts have been lost for political and religious reasons. The English Reformation, for instance, saw the dissolution of monasteries and the enormous collections of literature they housed, much of which was lost in the aftermath. But manuscripts were also destroyed for more senseless. Ironically, many were destroyed to use as raw materials for the binding of printed books.

During Phillipps' time, though, his major concern was vandalism. Some manuscripts still have missing pieces, from people cutting out the carefully penned illustrations, but the most egregious destruction was the work of "goldbeaters." As "A Gentle Madness" explains, these were the people who only cared about extracting the inlaid precious metals from old manuscripts. Illuminated manuscripts are those containing elaborate (and sometimes bizarre) artwork alongside the writing. The finest of all are gilded manuscripts which, as the British Library mentions, are embellished with gold or silver. In some, this was applied as a special ink, while others used gold leaf. Phillips' goal was to make people realize that these old documents were more valuable than the gold they contained.

Broadway Tower and the Middle Hill Press

The Phillipps family home was a large country house, Middle Hill, Broadway, in Southern England. It was this place where Sir Thomas Phillipps had originally begun to collect books as a boy, and when he became more serious about collecting literature, he stayed quite nearby. As the Broadway History Society explains, he collected books while studying for a degree at University College Oxford. While he was awarded various societal honors thanks to his family connections, those books remained his primary interest. Using inheritance money, Phillipps later purchased Broadway Tower.

Inside Broadway Tower, Phillipps set up a printing press which he used to print transcripts of historical documents, each signed with the crest of a lion and the words "Sir T. P./Middle Hill," as a mark of authenticity. The tower itself is an ostentatious building, with a view over some of England's most famous landscapes. Built for the sake of aesthetics, architecture, and artistry, Phillipps' purchase of it was completely unexpected. Exhibition plaques at Broadway tower explain how he ended up using the Middle Hill Press to print and distribute copies of books that had never been published before. Finding comfort in his collection, he distributed printed copies freely to libraries and welcomed visiting scholars to study his collection. Academics would sometimes speak enthusiastically of Phillipps' hospitality, with one French scholar describing Broadway Tower as "a lighthouse" at which "all pilgrims of learning are made welcome."

A grand library

Despite keeping a careful catalog of his purchases, Sir Thomas Phillipps was famously not the most organized of collectors, but he still acquired an incredible collection. The book "Some Keywords In Dickens" suggests he may have been an inspiration for the Dickensian character Mr. Krook, with his heaps of unread papers. It's easy to imagine that Phillips may never have read all of his collection, as he would eventually own roughly 50,000 books and 100,000 manuscripts. He even extended to collecting other documents too, including maps, master drawings, deeds, genealogical charts, and even much older items like Babylonian cylinder seals. His collection grew so large that it eventually rivaled those of entire universities.

Towards the end of his life, Phillipps' collection became something of an obsession. According to "A Gentle Madness," he was quite candid about this, once writing, "I wish to have one copy of every book in the world." A lofty goal that he seemingly came closer to achieving than anyone else in history. While ever passionate about books, Phillipps would eventually become far less agreeable towards people. Some came to describe him with words like selfish and obstinate, although it appears they may have believed Phillipps' library was an exercise in his own vanity rather than being about the preservation of documents. However, even those who didn't like him, still admitted that his life's work as a collector of literature was "heroic in conception and execution."

The cost of collecting

Many modern bibliophiles joke about buying books they can't afford, but it's safe to say that Sir Thomas Phillipps was far worse in this regard than any other book collector. He was a wealthy man, but the fortune he spent on his collection was far larger than the fortune he actually possessed. Seemingly no one was entirely sure what the total price tag was. Christie's Auction House mentions that a book trader and librarian, A.N.L. Munby, estimated that Phillipps likely spent up to a quarter of a million pounds, and as much as £5000 per year. Adjusted to modern prices (calculated from 1850 values via the Bank of England Inflation Calculator and xe.com), this is somewhere around £23 million ($27 million) in total and £470,000 ($563,000) per year.

Constantly spending such an absurd amount of money on books and manuscripts was, needless to say, completely unsustainable. Phillipps inherited a sizeable amount of money from his father, but this was evidently not enough to slake his nigh unquenchable thirst for books. As the Online Archive of California mentions, the result was that Phillipps found himself in near-constant debt.

Collector or hoarder?

Despite the fantastic treasures in his collection, Thomas Phillipps was notoriously disorganized, and a paper in the journal History of European Ideas even refers to his home as a "manuscript midden." An ungracious description, perhaps, but it certainly gives a stark impression of the chaos of Phillipps' ever-growing library. His contemporaries painted a picture that is no less grim. The book "Some Keywords In Dickens" mentions an account written by Frederic Madden, a 19th-century curator of the British Museum's manuscript collection. About visiting Phillipps' home, he wrote, "The house looks more miserable and dilapidated every time I visit it."

Describing Phillipps' home as a "wretched abode," Madden describes in detail the way the house was stuffed full of large boxes of manuscripts. Every room was apparently filled with large piles of papers, manuscripts, books, and all kinds of other literary clutter heaped on tables, chairs, ladders, and even beds. Every room was filled with boxes, housing the most valuable of Phillipps' acquisitions, which were piled all the way up to the ceiling. Madden's account also notes that the air in Phillipps' home was stifling because of the windows never being opened, saying that the house had an "almost unbearable" smell of paper and parchment. While, as Psychology Today notes, it's in poor taste to make light of hoarding, Madden's account certainly seems to suggest that Phillipps developed something of a hoarding mentality as he let his collection get the better of him.

Moving the collection

In 1863, Sir Thomas Phillipps set about the colossal task of moving his entire collection to a new home. At this point, his personal library, disordered as it was, needed an entire workforce to move it. According to the book "The Shakespeare Thefts," he hired 175 men and 250 horses to pull 125 wagons for the task. And while the location to which he was moving was only 20 miles away, the entire operation still took two years. The new home of both Phillipps and his collection was a mansion, Thirestaine House, a building so large that food from the kitchens was always cold by the time it reached the dining room – much to the displeasure of Lady Phillipps. To cement the house as the new home of his collection, Phillipps then wrote in his will, that every last book was to remain there indefinitely.

Phillipps' extreme measures were all because of a family dispute. By now, his daughter Henrietta had married a man named James Orchard Halliwell, a scholar of Shakespeare with a dubious reputation. Halliwell was reportedly a book thief, accused of stealing texts from Trinity College Cambridge. While the charges were eventually dropped, many continued to cast suspicious eyes at him. Phillipps in particular, as a book collector, refused to trust Halliwell. As the book "Eccentric Lives and Peculiar Notions" explains, the move was to ensure that Phillipps' collection would never fall into his son-in-law's hands.

Phillipps' legacy

Towards the end of his life, Sir Thomas Phillipps tried to find a new home for his enormous collection of literature, but to no avail. As a paper in the journal Speculum notes, while he made inquiries with both the British Museum and Oxford's Bodleian Library, no arrangements had been concluded by the time of his death. In the end, his collection was inherited by one of his daughters, Katharine Fenwick, by decree of his absurdly restrictive will. "A Gentle Madness" explains that Phillipps' will was described as impossible, stipulating that his books should forever remain in Thirlestaine and that they should never be viewed by Roman Catholics. He also emphasized that James Orchard Halliwell, in particular, should never be allowed near them. Phillipps' other son-in-law, John Fenwick, reportedly said of Phillipps that he'd "pleased no one in life, and I expect he has managed to displease everyone in death as well."

Eventually, Phillipps' will was overturned because of how unworkable it was. Reportedly, it took a century of sales and auctions to sort through the mountain of texts. While Thomas Phillipps may have wanted his collection to be kept together, it has since been dispersed to the four corners of the world. As a blog from the London School of Advanced Study mentions, texts collected by Phillipps can now be found around the globe, in both public collections and private hands. Residing in places from the USA to India to Australia, some are now exceptionally far away from Thirlestaine House.

Bibliotheca Phillippica

Sir Thomas Phillipps may not have been the best-liked man in life, but he certainly left his mark on the world. As the London School of Advanced Studies notes, despite many difficulties, Phillipps played an important role in preserving many of the items in his collection. A paper in the journal Manuscript Studies mentions that several items from his collection, sometimes called the Bibliotheca Phillippica, are now kept in North America, including documents from the European colonial era.

By far the most valuable items from Phillipps' collection, however, are illuminated manuscripts: treasures from medieval times, carefully handcrafted with beautiful illustrations. One particular item is the 14th-century Rochefoucauld Grail. Medievalists.net explains that this manuscript, with its many vivid illustrations, is a collection of Arthurian legends, about the quest for the Holy Grail. It's lauded as one of the first significant pieces of secular medieval literature, full of energetic imagery. In 2010, it was sold by Sotheby's auction house, at a price of just under £2.4 million (just under $2.8 million, via xe.com).

The collection of Sir Thomas Phillipps may have been housed in disarray, but had he not kept manuscripts like the Rochefoucauld Grail safe, there's a fair chance that many of them might not have survived to the modern day. Phillipps' goals in life were to keep these old texts safe from harm and to convince the world of their true value. In that regard, it's quite clear that his life's work was a success.