Hyperpolyglots – The Truth About People Who Speak More Than 11 Languages

If you can read this, then you're one of 1.35 billion English speakers who make up just under 17% of the world's population. English, as Babbel explains, is the world's most widely spoken language, in no small part thanks to the legacy of colonialism. Most are second language speakers. Only 360 million people speak English as their first language, and native language speakers in Chinese and Spanish outnumber anglophones.

Elsewhere, however, the world contains more languages than most people might realize. In fact, according to ERIC Digest, an estimated 6,000 different languages are spoken around the globe — a notable disparity with there being only around 200 countries on Earth, and less than a quarter of them recognizing more than one official language. Multilingualism, the use of more than one language, is everywhere.

For most of the world's population, speaking more than one language is the norm. The Linguistic Society of America notes that most people alive today are bilingual or multilingual, and a European Commission report mentions that this includes more than half of all Europeans, no doubt as a consequence of having so many different languages and cultures in close proximity. However, a small handful of people speak many more than one or two languages, and can strike up casual conversations with people from various cultural backgrounds. As The New Yorker explains, these people are known as hyperpolyglots — and some of them prefer to avoid speaking English on principle,

Historic Hyperpolyglots

The word "hyperpolyglot" is a relatively new invention, a term for anyone speaking even more languages than a regular polyglot. As Babbel mentions, it was coined around 20 years ago, with the original definition as someone fluent in at least six languages — although, as The New Yorker notes, the newer definition requires 11. The word may be relatively new, but the people themselves have existed throughout history. Several ancient leaders reportedly spoke a variety of languages. Queen Cleopatra of Ptolemaic Egypt was said to very seldom need an interpreter, while King Mithridates VI of Pontus ruled over 22 nations, and is said to have written laws in as many languages. More recently, Queen Elizabeth I of England spoke in the many languages of the British Isles, including Cornish, Welsh, and Scots Gaelic.

The gold standard for historic hyperpolyglots, however, was Cardinal Giuseppe Mezzofanti. As The Guardian explains, Mezzofanti was born in Bologna, Italy, in 1774, and was said to have spoken an exceptional 70 different languages, able to switch effortlessly from one to another when in the company of a group. Not far off Mezzofanti's skill was an early 20th-century German diplomat named Emil Krebs, who was able to converse in 65 languages. It may be difficult to judge how truthful historical accounts may be, and how much is exaggeration, but it's certainly easy to believe these people truly had the language skills with which they're credited. Moreover, their contemporary counterparts indeed show that learning a vast number of languages is entirely possible.

Learning languages

For many, learning a new language can be a challenging endeavor — it takes quite a lot of brain work. As BBC Future mentions, the human brain has a few different systems to form memories, and learning a language uses all of them. But the effort pays off with a variety of benefits, improving memory and attention span, while helping to stave off dementia. What's more, there's some evidence that learning one language will improve your ability to learn another, leading to a snowball effect when picking up future languages. A study published in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review looked at people who'd recently picked up a second language, finding that unusual new words were easier for bilingual people to learn. To paraphrase ESL, the more languages you know, the easier it is to learn more.

Perhaps the key to learning new languages, however, is to have a passion for it. A hyperpolyglot named Luis Miguel Rojas-Berscia is mentioned in The New Yorker, and he talks enthusiastically about his passion for speaking. As a self-described "amoureux de langues," he explains that once he falls in love with a language, he simply has to learn it. This motivation works wonders for him, as he's living proof that a hyperpolyglot can pick up a new language with remarkable speed. Reportedly, in just a week, he learned enough Maltese to sound like he'd been living in Malta for a year.

The brain of a language learner

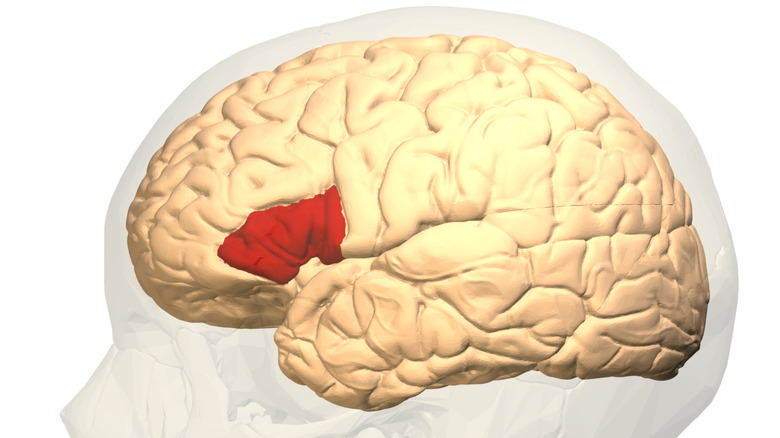

There are no definitive ways to tell if someone might be predisposed toward a heightened skill with languages. As The New Yorker notes, a hyperpolyglot is statistically most likely to be gay, male, left-handed, and with some form of autism. However, these aren't hard and fast rules, and neuroscientists are actively researching the brains of hyperpolyglots to learn more about linguistic capability and language learning. One important place to look is a part of the brain known as the Broca's area. According to the textbook Evolutionary Neuroscience (via Science Direct), this is the part of the brain responsible for speech and language understanding, a fairly small area near the front of the brain, highlighted in the image above.

The interesting part is that it's impossible to say whether the ability to be a hyperpolyglot is something people are born with — or whether it's something people develop into, simply by continuing to learn new languages. Babbel notes that some scholars hold the stance that hyperpolyglots are essentially "born to be made," having a set of traits like curiosity, enthusiasm, and dedication for language learning. Neuroscientists have noticed some interesting things in the brains of hyperpolyglots, too. The Washington Post makes mention of one somewhat surprising finding: While you might expect the language centers of a hyperpolyglot's brain to be larger and better developed, like a well-exercised muscle, the opposite is true. Hyperpolyglot brains actually have smaller and quieter language centers than those of monolinguals.

The neuroscience of multilingualism

In a hyperpolyglot's brain, the smaller language centers are much more efficient, and this seems to be key to their abilities. A study in the journal Cerebral Cortex explains that a hyperpolyglot's brain can process language information more easily. Essentially, the brain of a monolingual person needs to work a lot harder to parse language than the brain of a hyperpolyglot. Neuroscientists point out, though, that it's unclear whether they were born this way, or whether their brains developed this trait over time. If it were the latter, it suggests that anyone could hypothetically learn to become proficient in multiple languages.

During any kind of learning, an important factor is known as neuroplasticity, which determines how easy it is for your brain to form new pathways, causing physical changes in your brain through growth and reorganization. All humans have the highest neuroplasticity as young children, while our brains are still developing, but it can be influenced by learning new skills later in life too, and one of the best ways to improve neuroplasticity is language learning. A paper in the journal Cortex found that learners of second languages show dramatic increases in the gray matter of their brains, even with short-term learning, and at any age. Another study, published by Frontiers in Neuroscience, focused on older individuals: They found that language learning can show a substantial improvement in overall cognition, suggesting it may be helpful in promoting healthy aging.

Understanding languages and understanding people

Learning languages doesn't only benefit your brain: Seemingly, it can also promote a healthier outlook on the world. For example, a paper in the journal Lingua reports a study that found multilingual people are significantly more accepting of immigrants, explaining that multilinguals potentially have greater empathy, helping them to connect with immigrant populations. The idea that language is linked with an overall worldview is known as the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, and The International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (via Science Direct) explains this as the concept that the language that someone speaks influences their view of reality. It was dramatized in Denis Villeneuve's 2016 movie "Arrival," and, while the movie presented a much more fantastical depiction, the concept has its roots in real-world science.

There are essentially two versions of the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: The strong version is that language determines thought, while the weak version is the subtler idea that language influences thought. While there's no empirical evidence for the former, experts consider the latter rather more plausible. While it's an interesting topic to consider, there's been relatively little solid research done on the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, but hyperpolyglots may be able to help with future studies on the subject. One well-known hyperpolyglot, Dr. Yebra Lopez, has even given a talk on the hypothesis. His conclusion though, in brief, is that while there may be some truth to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, the outlook is still very much the same in any language: ultimately, we all see the same world.

Language, culture, and empathy

All languages come with attached culture, from popular sayings to mannerisms, and this is a substantial part of language learning. As The New Yorker mentions, some hyperpolyglots consider these "rules of behavior" just as important as the language itself. BBC Future notes that keeping space in your mind for the cultural experiences surrounding a language can help keep it active, and that learning a language isn't just about the amount of time spent, but the quality of that time, including the emotional and cultural aspects. Indeed, there's some evidence that people who can better empathize with the speakers of a given language are better able to learn that language. For example, one study in the Japanese journal Business Review found that people who're "better able to put themselves in other's shoes" are more fluent in their second language.

An article in The Washington Post talks about a hyperpolyglot named Vaughn Smith, whose experience reflects this idea of empathy. For him, the act of learning languages isn't an abstract notion of simply speaking different words, but a way of finding a connection with people, with each language becoming a story about that connection. In Smith's case, he likely also had an early start, thanks to his mixed ethnicity and multinational family. According to the Urban Institute, the children of immigrants are frequently multilingual, and a study in Brain and Language found that just being exposed to other languages can make learning easier.

Multilingual culture

While many native English speakers live in largely monolingual societies, there are plenty of places in the world that can be good places to nurture polyglots and hyperpolyglots. Treehugger mentions a few. Singapore has four official languages, while South Africa has a whopping 11 — not too surprising considering, as Harvard University notes, Africa in its entirety is home to somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 languages.

Some cultures even weave their multilingualism into their art, and an excellent example of this is Latinx poetry. "The Oxford Handbook of Latino Studies" explains how the poets of Latin America write in Spanish and English, including the hybrid Spanglish, and make use of code-switching between languages. In addition, as Poetry Foundation mentions, Latinx poetry can also include other languages from Latin America, such as Portuguese, as well as indigenous languages like Nahuatl and Mayan.

Being all about the creative use of language, poetry is an artistic medium in which multilingual people may find a lot of appreciation, and some hyperpolyglots have become successful poets. One example was the essayist Minnetta Theodora Taylor, a suffragist in the early 20th century who reportedly spoke numerous languages. However, it's unclear exactly how many languages Taylor spoke, with the Library of Congress blog saying 45, while the book Poets and poetry of Indiana says just 17, a reflection of the hyperpolyglot trait of being fluent or conversational in some languages but familiar with several more.

A community for hyperpolygots

Hyperpolyglotism is quite a rare skill, with people who speak so many languages making up just a tiny fraction of the world's population, yet they have their own dedicated community. 2016 saw the formation of HYPIA, the International Association of Hyperpolyglots, and, as of 2021, they had over 250 members from 60 countries worldwide, representing over 160 languages between them. To any hyperpolyglots eager to speak the languages they know, membership is doubtless an exciting prospect, and the success of HYPIA is reportedly thanks to the enthusiastic engagement of its members, as much as the time and effort its directors have put in.

Some hyperpolyglots have been described as "reclusive savants who bank their languages rather than using them to communicate," as per The New Yorker, but this may be a rather unfair assessment. Some, like Vaughn Smith (interviewed by The Washington Post), don't seem to feel the need to boast about their abilities. When the motivation to learn languages is for the pure joy of it, rather than for the sake of utility — such as for hyperpolyglots like Smith — it's enough to simply enjoy the act of speaking their languages, while otherwise living perfectly ordinary lives.

How many languages?

A common question asked of hyperpolyglots is, "how many languages do you speak?" As The New Yorker mentions, this is something that hyperpolyglots generally don't much enjoy being asked, often wincing on hearing the question. Seemingly, the more someone understands the subtle intricacies of languages, the less meaning this question has. It raises further questions about accents and dialects, the standard grammar of the ruling class, and the inherent chauvinism of judging someone by whether they "pass" as a native speaker. The full nuances of any language are difficult to master, even for native speakers themselves – speakers of Spanish and English, for example, will likely be familiar with how much intercontinental variation their languages contain.

Other hyperpolyglots, as The Washington Post describes, dislike the idea of trying to formalize their abilities. The languages these people speak are often self-taught, and they tend not to be particularly interested in participating in studies on the matter, instead simply being excited at the opportunity to flex their language skills and speak to people. While most people may be curious and amazed by how many languages someone can speak, the hyperpolyglots evidently consider this kind of examination the least interesting part of their experience.

Preserving dying languages

While the world has thousands of languages, a substantial number of them are at risk. According to The Language Conservancy, around 2,900 languages worldwide are at risk of becoming extinct, and, at the current rate, it's estimated that about 91% of all languages may be lost during the next century. In addition, many endangered languages are spoken by indigenous peoples. For example, the non-profit organization Native Languages of the Americas notes that of over 800 Native American languages spoken today, around 500 of them are endangered, and the Australian National University warns that about 1,500 indigenous Australian languages may be lost by the end of the century. Another is Hawaiian: As Mango Languages explains, UNESCO lists Hawaiian as a critically endangered language, with only around 2,000 native speakers.

Hyperpolyglots may be able to play a valuable role in the conservation of languages, helping to prevent them from being lost by ensuring that they're still being spoken. Meanwhile, revival efforts can be made to teach these languages in schools, to ensure a new generation of speakers will be able to carry on their traditions. Some hyperpolyglots are well aware of this fact, and one of the stated goals of The International Association of Hyperpolyglots (HYPIA) is a commitment to the preservation of dying languages. They even have a special membership category for people who speak fewer than the required six languages, if one of them is endangered.