The Untold Truth Of The New Hollywood Movement

The Golden Age of Hollywood was a legendary time in cinema that's easily recognizable. Between the 1910s all the way to the 1960s, Tinseltown was controlled by five major studios: Paramount, Fox, MGM, Warner Bros., and RKO. According to StudioBinder, these studios controlled everything when it came to making a flick: from the shooting locations to the distribution to casting — in fact, they had complete ownership over their stars, too.

Suddenly, things started changing by the late 1960s — 1967, to be exact. A new crop of American directors, who were influenced by various cinematic movements abroad, grew tired of the formulaic, conservative filmmaking they had seen for decades — not to mention they were part of a new generation that was unwilling to conform, cynical to what was going on in the world, such as the Vietnam War (via NewWaveFilm).

As such, the films that started cropping up appealed to this baby boomer audience and counterculture movement, focusing on sociopolitical issues and seeing a rise in violence, sex, and drugs on camera, per Filmmaking Lifestyle. Some key auteurs of this time included Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich, Martin Scorsese, and Brian De Palma. This new direction in filmmaking would become known as the New Hollywood movement or the Hollywood New Wave, so let's take a look at some of the defining moments of this revolutionary period in cinema.

In the 1950s, Hollywood was heading out of fashion, competing with television

The height of the Great Depression in the 1930s was coincidentally also the time that Hollywood's Golden Age was thriving. According to History, while the general public was no doubt financially struggling, people still yearned for a trip to the cinema as a means to be whisked off to a glamorous world.

Tinseltown continued to reign supreme during both World Wars, yet by the late 1940s, things started changing. 1948 was the year the Supreme Court issued a decision against the leading film studios in the country in the Paramount antitrust case (United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc.), per NewWaveFilm. It ruled that these studios couldn't own their own movie theaters (in turn, only playing their own films). As a result, the influence of these studios severely declined.

To make matters even more difficult, by the 1950s, the rise of television also spelled disaster for Hollywood, as audiences preferred to stay home instead of heading to a theater to watch a film (via History). "It was the unparalleled last 10 years that did the [movie] Empire in," declared an article by Life magazine in 1957, dubbing the '50s "the horrible decade" in filmmaking. Noting that studio heads who once reigned supreme were slowly being replaced by independent producers, it was already apparent that a significant change was on the horizon. New Hollywood was ready to make its mark.

Inspiration from abroad

The best part of the New Hollywood movement was that the leading directors of the era were genuine cinephiles, uninterested in making vapid commercial pictures, and instead, were bursting with inspiration from countless foreign filmmakers they loved. According to The Mancunion, these New Hollywood directors became known as the "movie brats," who spent their youth soaking up the works of auteurs such as Ingmar Bergman from Sweden, Italy's Federico Fellini, Francois Truffaut from France, and the Japanese director Akira Kurosawa (via StudioBinder).

These movements stirred the movie brats at a time when domestic filmmaking was at an all-time low: Audiences grew tired of the overstuffed epic, while westerns simply grew out of style. For Martin Scorsese, his leading inspiration came from Italian neorealism and, in particular, the films of Fellini, Roberto Rossellini, and Vittorio De Sica (via StudioBinder). On the other hand, Brian De Palma sought influence from the French New Wave movement, citing Jean-Luc Godard's impact. "Godard's a terrific influence, of course. If I could be the American Godard, that would be great," he mused in 1968, per NewWaveFilm.

The result of the New Hollywood movement didn't push out the classic genres of Tinseltown: It simply changed them. As New Wave Film notes, genres such as war films, westerns, and crime flicks were given a unique, stylistic edge, better portraying the state of the country and redefining what it was audiences were looking to see on the silver screen.

The movement started with Bonnie and Clyde

The Arthur Penn-directed neo-noir crime flick "Bonnie and Clyde" kicked off the New Hollywood movement in 1967 (via The Mancunion). Interestingly enough, nobody thought the film would leave such a lasting impression on cinema, and initially, it proved to be exceptionally difficult to get the movie made.

As detailed by NewWaveFilm, the idea to pen a script about the lives of real-life gangsters Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow came by way of two young writers: Robert Benton and David Newman. Although they didn't have much professional experience, they were influenced by Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard of the French New Wave movement, and, in particular, the moral dilemmas of the characters in "Breathless" and "Jules and Jim."

Warren Beatty, who played Clyde, found out about the movie from Truffaut himself and, after reading the script, declared he wanted to produce the film as well. The actor reportedly pleaded to studio head Jack Warner of Warner Bros. to finance the film, who finally agreed, yet after the movie's release, absolutely hated it. The result was a limited release with a few negative initial reviews, yet audiences gave it a second chance after The New Yorker's enthusiastic evaluation.

In 1968, "Bonnie and Clyde" was nominated for a whopping 10 Academy Awards (winning two, via the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences), but its influence was much more impactful. As the BBC writes, thanks to the film's gratuitous violence, it changed the entire rating system, leading to the release of the Motion Picture Association of America film-rating guidelines, still in use today.

The Hays Code was finally abolished after nearly four decades

Throughout the Golden Age of Hollywood, movie censorship guidelines reigned supreme in what was called the Hays Code, a set of rules that came into play in 1930. According to NPR, these rules sought to maintain Americans' moral values, prohibiting any nudity, sexual innuendo, and the use of alcohol on camera, among a handful of other "sinful" acts.

"Hollywood in the 1920s is a super racy time," explained curator Chelsey O'Brien to ACMI. "There were off-screen stories of drugs and alcohol and partying and overindulgence," O'Brien added, noting that real-life scandals in the industry mimicked some of the questionable content audiences were seeing on camera. Remarkably, the Hays Code lasted almost a whopping four decades and was finally abolished in 1968 — a year after the release of two incredibly influential movies: the blood-soaked "Bonnie and Clyde" and the sexually liberating Mike Nichols comedy "The Graduate," per CNN.

With the Hays Code gone, the floodgates were suddenly open, and the New Hollywood movement was defined by themes of sex, violence, and other "shocking" visuals. One of the most controversial films of the era was 1969's "Midnight Cowboy" — the first best picture winner at the Oscars with a daring X-rating. As movie historian and film studies professor Jon Lewis told CNN, "It's a film about — not a gay [sex worker] — but he engages in gay sex acts for money. I can't even imagine suggesting that pre-1968."

The importance of 'Easy Rider' and The Graduate

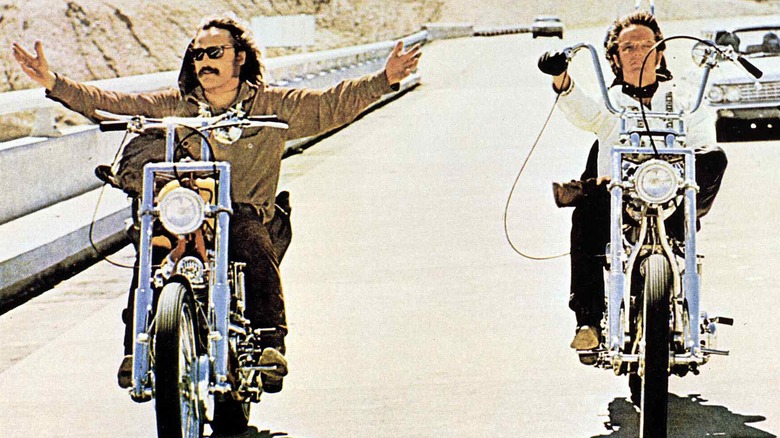

Along with "Bonnie and Clyde," which kicked off the New Hollywood movement, two other movies proved to be influential for this time: 1967s' "The Graduate" and "Easy Rider," released two years later. Both films are noteworthy for highlighting the changing ideals of the country and showcasing characters that the younger generation could relate to.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, "The Graduate" was based on a 1963 novella of the same name, and while the book wasn't popular, much of the film's dialogue was taken directly from author Charles Webb (via Criterion). As baby boomer audiences followed recent graduate Benjamin Braddock's seduction by his neighbor Mrs. Robinson, they, more importantly, related to his anxiety about picking a career path — making it a defining film of this younger generation, per Vox.

"Easy Rider," on the other hand, took things a step further when it came to the generational gap, showcasing the American counterculture movement in the form of a road trip flick. As The Mancunion explains, viewers watched two hippy bikers travel across the country selling drugs, all while encountering prejudiced "normal" folk who rejected their lifestyle.

Interestingly enough, these two films also had one significant similarity: the "jukebox" style soundtrack. Per No Film School, "The Graduate" opted for a soundtrack composed of Simon and Garfunkel songs instead of an orchestral score, while "Easy Rider" showcased popular artists of its time, such as Jimi Hendrix, Steppenwolf, and The Byrds.

New Hollywood auteurs weren't confined to the needs of major studios

As Hollywood's Golden Age came to a halt in the late 1940s and '50s, some film studios were forced to shut down, while certain studio heads, screenwriters, and actors either retired or simply stopped making films (via History). "It is no longer possible to filter the total production of one company through the mind of one man," declared one executive at Fox to Life magazine in 1957, showcasing the declining power of these studio heads.

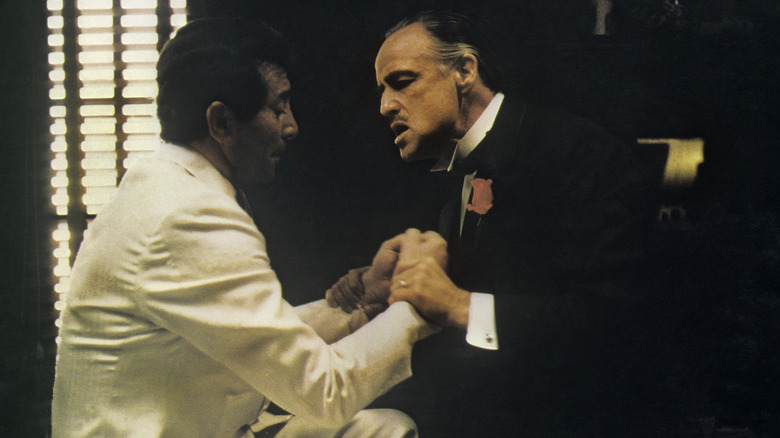

With the influence of major studios dwindling as the New Hollywood movement began picking up steam, this meant that directors had a lot more control of the final product they were making and, in turn, saw their careers thrive, according to Boxoffice Pro. One such filmmaker was Francis Ford Coppola, who was thrust onto the A-list with his 1972 crime epic "The Godfather," winning himself his first Academy Award at the age of 32 (via Filmmaking Lifestyle).

As noted by BoxOffice Pro, a defining factor of these New Hollywood movies was that they usually had a significantly smaller budget than the studio films of the Golden Age while also swapping out traditional on-screen formulas for themes that placed the spotlight on youth culture and sociopolitical issues.

The civil rights movement was also influential in New Hollywood

It wasn't just a flurry of sex, drugs, and violence that infiltrated the films of New Hollywood; The industry was also rocked by the civil rights movement. As "The Persistence of Hollywood" explains, it's not since the Great Depression of the 1930s that America experienced such drastic social and political disturbances, citing the period between Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination in 1968 and President Richard Nixon's resignation in 1974 as an influential time for Tinseltown.

According to BoxOffice Pro, up until the '60s, Hollywood was still incredibly — and openly — racist. Some movie theaters were still segregated, while other cities didn't even have Black-run cinemas altogether. The civil rights movement started gaining traction among the younger generation, and finally, in July of 1964, the Civil Rights Act took hold, and with that came the end of legal segregation, meaning all cinemas across the country had to abide by the new law.

Meanwhile, in Tinseltown itself, minority representation was finally being questioned, with the late Sidney Poitier becoming the first Black man to win an Academy Award for best actor for his role in "Lilies of the Field" in 1964. A few years later, with King's assassination in 1968, Poitier, along with fellow industry A-listers such as Paul Newman, Marlon Brando, and Candice Bergen, banded together to form a nonprofit group focusing on making films that highlight racial and social issues across the country (via BoxOffice Pro).

Innovative filmmaking techniques led to the rise of location shooting

Aside from the significant shift in storytelling as a part of the New Hollywood movement, innovative filmmaking techniques also drastically changed the way movies were being made. As Newsshooter explains, with the rise of television's popularity in the 1950s and early '60s, Tinseltown knew it needed to create something to set it apart from the small screen. The solution was to start shooting widescreen, high-quality flicks rich in color and sharpness — a style that Panavision refined.

Panavision was founded in 1954 by Robert Gottschalk, who began working on getting rid of the distortion that came from projecting a film on the big screen (via the Los Angeles Times). In 1959, "Ben Hur" became the first movie filmed on a Panavision lens, winning an Oscar for best cinematography. As the glamor of Old Hollywood started to subside with the New Wave movement picking up speed, so did Panavision's technical capabilities. The company spent the 1960s perfecting the Panaflex camera: a portable camera that suddenly allowed cinematographers the luxury of easily shooting on location, away from Hollywood studios.

According to Panavision's website, the Panaflex was released to the public in 1972. While handheld cameras weren't new at this time, Panaflex was silent, making it easier to sync sounds to visuals (via in70mm.com). As "Hollywood on Location: An Industry History" notes, location shooting dominated like never before, and by the 1980s, jobs for location scouts and production liaisons were booming.

The start of the 1970s saw the rise of midnight movies

Thanks to the establishment of the Hays Code in the 1930s, Hollywood films spent nearly four decades devoid of any "taboo" imagery. While these "controversial" topics didn't make their way to the big screen during this time, the 1950s saw the creation of the "midnight movie," a term initially used to describe films that were shown on television late at night.

As The Verge notes, midnight flicks between the '50s and the late '60s were mainly B-movies of the horror variety, yet as the counterculture movement evolved, so did these films. "Cult Cinema: An Introduction" explains that with New Hollywood's sudden influx of sex and violence on camera, movie theaters began catering to these tastes late at night, citing 1963's "Flaming Creatures" as the first true midnight movie that set off the momentum for more of these soon-to-be cult classics.

By the early 1970s, one thing was clear with midnight movies: The more radical they were, the better. "Cult Cinema" cites Alejandro Jodorowsky's acid western "El Topo" as one of the most successful films of this movement, while George A. Romero's "Night of the Living Dead" established that these art movies could be sociopolitical, too. Coinciding with the death of Martin Luther King Jr., Romero's horror classic starring a heroic Black lead suddenly took on a civil rights stance — even if the director didn't initially intend for that. As he told The Hollywood Reporter decades later, "All of a sudden, even in our minds it became a racial film."

The Sundance Film Festival was founded in 1978

The Sundance Film Festival has been around for decades, but did you know its roots are tied to the New Hollywood movement? According to The Globe and Mail, what's now considered the largest independent film festival in America started in 1978 as a little event called The Utah/United States Film Festival. Launched in Salt Lake City and featuring longtime Utah resident Robert Redford as chairman, the festival was meant to boost tourism, with the first year bringing in 300 attendees.

Along with the desire to boost Utah's tourism, the other main focus of this early festival was to highlight independent filmmakers who were tired of Tinseltown's overstuffed, studio-run pictures. As Sundance history biographer Peter Biskind told The Globe and Mail, Redford backed the festival because he believed that "Independents had something to say but didn't have the skills to say it, and that Hollywood had nothing to say but said it with great skill."

After speaking to director Sidney Pollack in 1980, Redford and the management team agreed to move the event to Park City instead. The following year, the legendary actor separately launched his Sundance Institute, and by 1984, the festival was moved there, renamed as the US Film Festival (via Vox).

After years of highlighting independent films, the festival was finally rebranded as the Sundance Film Festival in 1991. Since then, it's launched the careers of many celebrated filmmakers, such as Wes Anderson, Quentin Tarantino, and Darren Aronofsky.

The 1980s saw the end of the New Hollywood movement

Sadly, all good things must come to an end, which is precisely what happened to the New Hollywood movement. This period had already seen major technological strides in the early '70s when it came to Hollywood's cinematography, but by the end of the decade, the industry had also advanced in terms of computer-generated special effects (via History).

With so much creative power at filmmakers' disposal, the blockbuster movie was suddenly born. Some directors had already seen success releasing these massive, action-packed flicks during Hollywood's New Wave movement, such as Steven Spielberg's 1975 hit, "Jaws," which is widely considered the first-ever summer blockbuster. But it wasn't just "Jaws" that signified the end of the New Hollywood movement: that honor should also include 1977's first-ever "Star Wars" film. According to The Mancunion, while the movie was creative and was nothing like audiences had ever seen before, its success also marked the moment Hollywood studios began realizing the profitability of franchises.

Some film historians cite the end of the '70s, roughly 1976, as the end of the New Hollywood movement, while others point to the early '80s, after the blockbuster boom. The Mancunion credits the third installment of the "Star Wars" franchise, 1983's "Return of the Jedi," as the official culprit. While the ethos of the New Hollywood movement emphasized an artistic and daring take on cinema, the space opera (although successful) represented a different, consumerist angle that was ready to swallow the industry whole.