The Odd Life Of The World's Luckiest Millionaire, Timothy Dexter

Every life is a story, it's just that some lives are more interesting than others. Many born in modest circumstances might dream big: One might imagine working hard, securing a future, being able to retire one day, and heck, maybe even buy that boat. Others might dream even bigger: Go to Hollywood, become a star, live in a Beverly Hills mansion, buy that supercar, and pretend not to know the high school bully when they call and try to get all buddy-buddy.

And then, there's Lord Timothy Dexter.

Dexter would eventually write a book telling his life story, and it's quite the tale. It's the sort of thing better suited to one of Aesop's fables, perhaps, or Grimm's fairy tales. He was very real, though, and that just makes it even harder to describe just how bizarre this whole thing is.

According to the preface of his book — which was obviously not written by him, because this writer believed in both spelling and punctuation — he was born on January 22, 1747. And that's when things started getting really weird ... but first, a disclaimer. As might be expected with someone born into rather ordinary circumstances at the end of the 18th century, there's the occasional discrepancy in his tale. That's not entirely surprising ... there's a lot of tale to tell.

He really, really wanted to be rich and famous

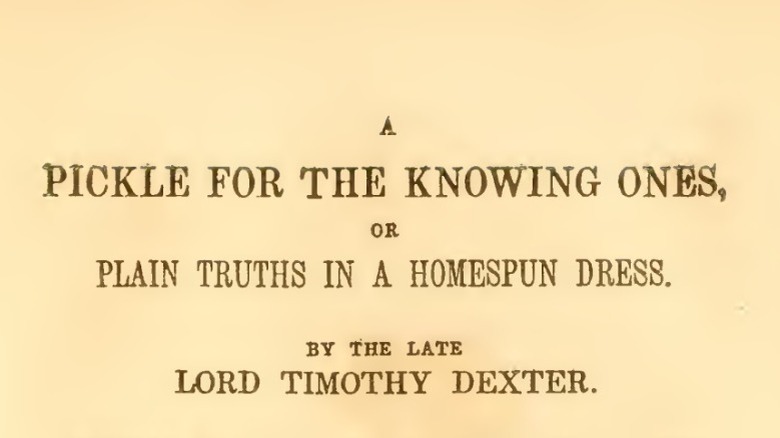

Timothy Dexter's story starts out perfectly normal, with one footnote. While the preface of his book — called, for some reason, "A pickle for the knowing ones" — says that he was born on January 22, 1747, other sources suggest his birthday was actually some time in the winter of 1748.

Either way, Priceonomics says that Dexter was one of a family of very essential workers: Farm laborers. Unfortunately, the agricultural sector didn't come with much in the way of financial security, and the idealistic teenage Dexter managed to get an apprenticeship with some Boston-based leather workers who had perfected a particularly in-demand product called Moroccan leather. Admirable? Absolutely. Good enough? Not for Dexter, and what happened next was the first thing in a string of incredibly improbable things that should have destroyed him ... but somehow, totally worked out.

Just as Dexter opened his own business, Boston shut down amid the historic events kicked off by the Boston Tea Party and turned into an outright revolution. Rather than try to ply his trade somewhere less rebellion-y, he stayed, optimistically moved to the well-to-do Charlestown area, and met a wildly successful door-to-door saleswoman (and absolute huckster) named Elizabeth Frothingham. The pair married, and for Dexter, that just happened to mean marrying into a small fortune.

Lord Timothy Dexter, Informer of the Deer

At the time Dexter and his new wife set up in Charlestown, it's safe to say that they were way out of their league. Dexter — who had ceased his formal education at the ripe old age of 8 — now had neighbors like John Hancock, arguably the most famous (future) signer of the Constitution. And sure, Dexter was a wealthy man now, but according to Priceonomics, he knew that if he wanted to secure the respect of his neighbors, he needed a job.

Dexter really wasn't qualified for a whole heck of a lot, but fortunately for him, there was always public office. He turned his attention to the nearby Malden and started petitioning them — a lot — asking for a job. They ultimately ended up inventing a post for him, and he was appointed "Informer of the Deer." His job duties? Count the local deer and keep track of the population.

There's a massive "but." He wasn't a respectable version of an early Department of Environmental Conservation officer, and he wasn't making sure the deer population was stable enough to hunt. As recorded in The History of Malden, the deer population was precisely zero, as they had all disappeared from the area long before Dexter was tasked with counting them.

Capitalizing on the downfall of a currency

The thing about money is that there never seems to be enough, and Timothy Dexter absolutely subscribed to that theory. According to Britannica, Dexter decided to start trying his hand at speculative trading, and at a glance, it didn't seem like he was going to be very good at it.

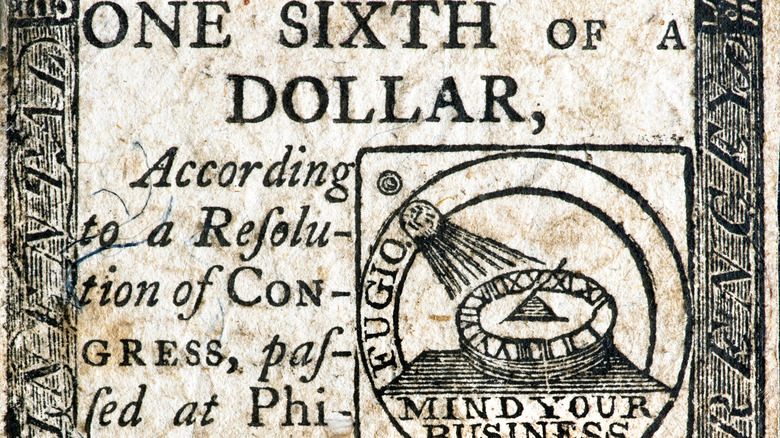

He was bizarrely — and almost accidentally — amazing at it.

His first venture involved buying a ton of Continental currency, and it's worth talking about why this should have seemed like a phenomenally dumb idea. According to Politico, the currency was first issued by the Continental Congress in 1775, to the tune of $2 million. It was meant to kick-start the economy of a baby nation waging a war for independence, but it wasn't actually backed up by precious metals like gold or silver... or literally anything else. It wasn't long before that $2 million turned into $240 million, and at the same time, the British took the opportunity to counterfeit the heck out of them and destabilize the whole thing ever further. The currency collapsed, and the bills became worthless: And that's exactly what he bought. He had a sneaking suspicion that it might all go back into circulation at some point, and he was 100% wrong.

Then, the 1790s rolled around, and his investment paid off in a big way. It was decided that all that currency could be traded to the government for bonds, and that's exactly what Dexter did. He made a fortune.

Bye, bye, Boston: Hello Newburyport

According to Samuel Knapp's "Life of Lord Timothy Dexter," it wasn't long before it became clear to the newly-made, ridiculously rich Dexter that people in Boston just didn't like him. (They also suggest that while it was almost definitely because of his abrasive personality, he was pretty sure it was everyone else's problem, not his.)

So, Dexter picked up his family and moved to Newburyport, where he bought two homes that Knapp describes as "palaces — for they could not, in justice, be called by a lesser name." One, he lived in for a bit then flipped, and the other? He put his own special spin on it in a way that can best be described as ostentatious.

The biggest addition was actually a whole bunch of additions: Dexter erected a series of 15-foot tall pillars, and on top of each of the pillars, he installed a massive wooden carving depicting a historical — or occasionally, fictional — character. In addition to Napoleon, there was also a goddess, at least one Native American chief, and patriots that including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. It was the statue of Jefferson that caused some serious strife between Dexter and his painter: As recalled in the forward to "A pickle for the knowing ones," Dexter insisted that the paper in Jefferson's hands be labeled "Constitution." When the painter pointed out that it should probably be the "Declaration of Independence," Dexter responded by trying to shoot the man. Fortunately, he just shot his house, instead.

He didn't know how to do a lot of things ... but he did them anyway

Money, it seems, had changed Lord Timothy Dexter. According to the novelist and historian John P. Marquand (via the New England Historical Society), Dexter had been a pretty unassuming sort of guy until he started raking in the cash. Marquand wrote that "he was ... not conspicuous until he suddenly made a fortune."

Dexter very quickly gained a reputation around town, and it was, well, something. The preface for "A pickle for the knowing ones" says that in addition to being well-known for his love of alcohol, he was also well known for shooting — or trying to shoot, or ordering his son to shoot — at least a few people. One stranger filed a complaint after he was shot at, and it ended with Dexter being sentenced to a few months in jail. (He bought his way out before serving the whole sentence.)

All That is Interesting says that one newspaper claimed his "ignorance was almost without a parallel in the United States of America," and some of the things he did definitely didn't do him any favors. He once gave an entire speech in French, in spite of not knowing how to speak French at all, and saying he gave it a shot just in case he did, in fact, speak French and just didn't know it. He regularly destroyed his own furniture, only tended to listen to a woman nicknamed "Black Luce," and still, he just kept making money.

How do you get rid of a bad neighbor?

Timothy Dexter took his statues pretty seriously, and the crowning achievement was one of himself. Historic Ipswich says that it bore the inscription, "I am the first in the East, the first in the West, and the greatest philosopher in the Western world." Was he? No, but it didn't stop him from saying it, or from declaring that he was no longer boring old "Timothy Dexter," he was going to be known as "Lord Timothy Dexter."

By this time, his wife was so embarrassed that she moved out. Fortunately for Dexter, that meant his son — who also loved drinking and women — could move in. (Dexter actually had two children, described by the author of his book's preface like this: "neither of whom was distinguished for strength of intellect.") After that, the neighborhood sort of went on a definite downhill slide. Dexter's mansion became something of a local brothel, but still — he apparently needed something to fill his days, so it was about this time that he decided to dabble in what had made him his fortune in the first place: trading.

After Dexter announced he was going to be buying himself a handful of ships and sending them off on international trade trips, his neighbors jumped on the idea. Priceonomics says that the idea was simple: Give him terrible advice, watch him fail, and see him leave town in shame. It didn't exactly work out that way.

That's when he really got started on international trading

Under the guise of being helpful, Lord Timothy Dexter's neighbors started giving him advice that they swore was good. Priceonomics says that it clearly wasn't, and included things like shipping bed warmers to the notoriously hot West Indies, and sending coal to one of the UK's biggest coal-producing cities, Newcastle. Dexter not only took the phenomenally bad advice and dispatched his ships with their seemingly ill-fated cargo, but he made a fortune.

While there was no need for bed warmers in the West Indies, the long-handled pans were actually perfect for something else. Once the owners of sugar and molasses plantations realized that these bed warmers made great ladles, they couldn't buy them fast enough, and Dexter made somewhere around a 79% markup on his investment. And the coal? Dexter's shipment arrival coincided with a coal miner's strike, and again, he made a mint.

Dexter's career as a trader is filled with audacious gambles that somehow always seemed to work out. He bought, for example, 340 tons of whale bones — almost all the country had. And then? It skyrocketed in value with the rising popularity of whalebone corsets. Even stranger? Dexter seemed to court disaster: The New England Historical Society says that one year, he bought all the stray cats in Newburyport, then shipped them to the Caribbean. It's unclear whether or not he knew there had been an explosion in the mouse population that year, but either way, plantation owners happily welcomed the once-unwanted strays.

The sad tale of Dexter's own poet laureate

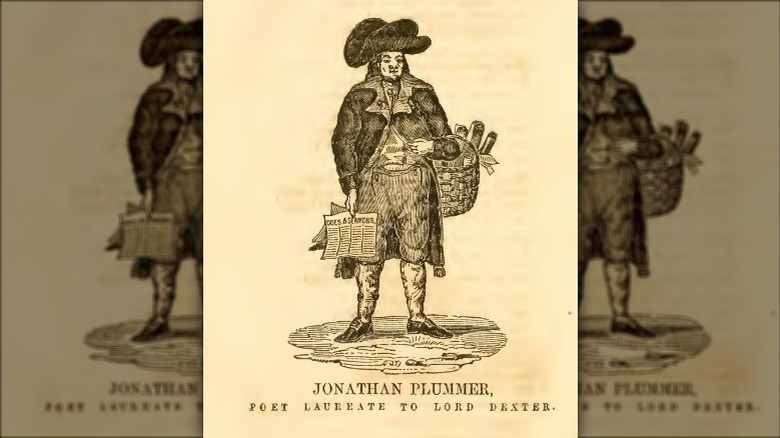

If there's one thing that Lord Timothy Dexter knew, it's that any lord, lady, or regent worth their salt had their own poet laureate. Does that mean he chose one for himself? Of course he did! According to Samuel Knapp's "Life of Lord Timothy Dexter," Dexter was trying to emulate England's kings when he chose a local man named Jonathan Plummer to be his official poet. "He was a strange and wayward boy," Knapp wrote, continuing to say that he had found his voice for the lyrical when he was at an outdoor meeting of "religious enthusiasts who worshipped God in the woods and fields."

By the time Dexter met him, Plummer had, in fact, decided that he was no longer going to push around his wheelbarrow of fish to sell, and instead concentrate on saving souls. That went by the wayside when Dexter hired him, though, outfitting him in an elegant black coat that was covered in fringe, even though Plummer was pretty sure it was sinful. Less sinful, apparently, was his crown of parsley.

Still, he got over it. The New England Historical Society says that Plummer composed a series of works lauding the mighty deeds of the good Lord Timothy Dexter, but there's not a happy end to his story. Dexter neglected to provide for his poet in his will, and after his death, Plummer wrote two books about him, fell into a deep depression, then died of self-starvation at age 58.

That time he faked his own death

Historians haven't been able to decide if Lord Timothy Dexter was incredibly smart, improbably lucky, or a combination of the two. Dexter's own writings don't really give much of a clue, as he once simply explained, "I found I was very lucky in spekkelation. Spekkelators swarmed me like hell houns." That, presumably, meant "speculation," says Priceonomics, but for all his wealth, Dexter found he couldn't buy what he really wanted. That, of course, was acceptance into society's elite, so it's not entirely surprising that he eventually decided that he wanted to know what people were going to say about him when he was dead ... while he was still around to hear them.

So, he staged his own funeral. The preface from his own book notes that he started by building a tomb in the basement of his summer home, then buying his own coffin. Then, he sent out death notices, which led to around 3,000 people showing up on the day of the funeral. Only a handful of his closest friends knew that he was actually still alive and observing the whole thing, and it turned out that he didn't like everything that he saw.

Everyone else realized that he was still alive when they heard the screaming: It wasn't a guest convinced they were speaking to the dead, but his wife. They were in the kitchen, where he was beating her for not acting appropriately upset at his pretend passing.

A Pickle for the Knowing Ones

Thankfully, Lord Timothy Dexter saw fit to preserve some of his story in his own words, and it's just as chaotic as one might hope for. "A pickle for the knowing ones; or, Plain Truths in a Homespun Dress" was published in 1802, says Britannica, and it's pretty amazing. Dexter took the opportunity to brag about his own successes, but he also made sure he did a bit of ranting about everyone he didn't like, too. Capitalization is completely random, spelling is even more random, and there's no punctuation — except until the very last page, which is just full of it, for the do-it-yourself reader.

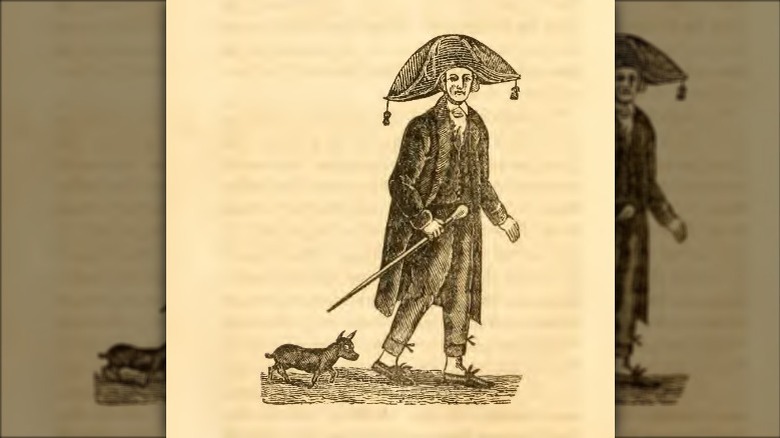

The result is a treasure trove of randomness, like "under the Cloak of bread & wine the hipercricks Cloven foots they Doue it to get power to Lie and Not be mistruested all wars mostly by the suf the broken marchents arefond of warfor thay hant Nothing to Lous." It also included an illustration of Dexter that was reportedly a faithful one, right down to his dog. (The dog, it was said, had the same sort of skin as an elephant, and "differed as much from other dogs as his master and his friend, the poet, differ from other people.")

Four years after the release of his book, Dexter passed away. It was October 26, 1806, and it was perhaps best summed up by the final line of his book's preface: "We ne'er shall look upon his like again."