The Tragic True Story Of The Texas City Disaster

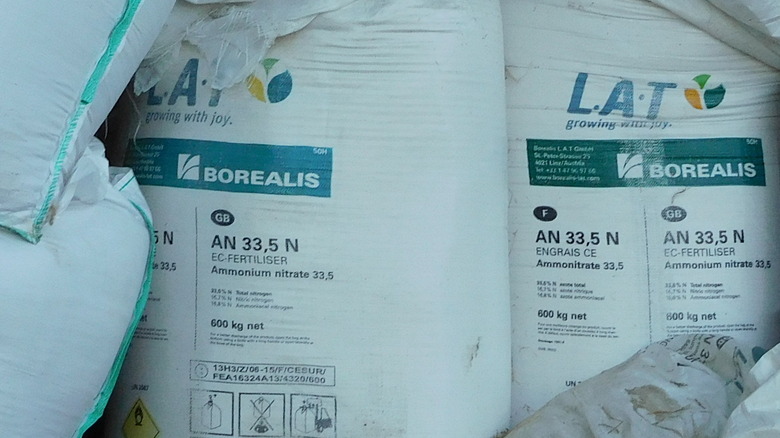

When an explosion rocked the port in Texas City, Texas in 1947, a seismologist in Denver, Colorado who recorded the shock waves thought that an atomic bomb had been detonated. Even the Strategic Air Command in Omaha, Nebraska thought that there was a nuclear attack. These weren't far-fetched assumptions. The explosion that destroyed Texas City ended up using 2,500 tons of ammonium nitrate. In comparison, the bomb used in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing used 2.5 tons of ammonium nitrate.

Although the Bhopal gas tragedy is the worst industrial accident in world history, as of 2022, the Texas City Disaster remains the worst industrial accident that the United States has ever experienced. Everything in the immediate vicinity of the port was destroyed, including small businesses, grain warehouses, oil and chemical storage tanks, and a nearby chemical plant. Hundreds of people lost their lives in the explosion, but the exact number may forever remain unknown.

After the disaster, the people of Texas City slowly rebuilt the town as several companies pledged to rebuild. But the road to recovery faced difficulties of its own. This is the tragic true story of the Texas City disaster.

Loading a shipment of fertilizer

Around Christmastime in 1946, the SS Grandcamp, a French cargo ship, set sail from New York City, New York. Traveling down the coast of North America to Newport News, Virginia, the Grandcamp then set sail across the North Atlantic to France and Belgium, picking up cargo along the way. Afterwards, it headed back across the Atlantic to Venezuela, and after stopping in Havana, Cuba, it set course for its final cargo pick up in Texas City, Texas, Bill Minutaglio writes in "City on Fire."

By the time the Grandcamp got to Texas City in April 1947, according to the Office of Response and Restoration, it was already filled with shipments of twine, peanuts, tobacco, and small arms ammunition. All that remained were the thousands of tons of ammonium nitrate fertilizer that was to be shipped to farmers in Europe, writes Interesting Engineering.

The Grandcamp arrived in Texas City on April 11, and during the loading, longshoremen reportedly noticed that the bags of fertilizer felt warm, which meant that "an increase in the substance's chemical activity was taking place." Although ammonium nitrate fertilizer is usually a relatively safe thing to transport, under certain conditions, like when a large quantity is exposed to intense heat, it can become unstable and explosive. This is why, in addition to being used as fertilizer, ammonium nitrate is also used as a military explosive.

Fire on the SS Grandcamp

The Grandcamp remained docked in Texas City for a few days as the fertilizer was loaded onto the cargo ship, which was slowed down due to heavy rains. Roughly 2,300 tons of ammonium nitrate fertilizer was already loaded into holds two and four when workers came out to finish the loading around 8 in the morning on April 16, 1947.

Upon entering the hold, workers noticed the smell of smoke. Soon, some also noticed smoke vapors. After removing a few small fertilizer bags, they were suddenly able to see the fire roughly 10-15 feet below. According to the Moore Memorial Public Library, workers first tried to put the fire out using jugs of water and a fire extinguisher, but to no avail. The fire department was alerted around 8:25 AM, but by the time two fire trucks arrived, the fire was heating up so quickly that water was unlikely to put out the fire.

Workers had also started moving the small arms ammunition out of the ship, fearing an explosion. But by the time the men were ordered to evacuate the ship, only three out of 16 boxes had been moved out of the hold. The Office of Response and Restoration writes that the ship's captain ordered the crew to batten the hatches and throw tarpaulins over them while steam was to be pumped into the ship. This was a firefighting technique, but unfortunately, it only made the situation worse.

Heard from 150 miles away

Instead of helping put the fire out, the steam made the situation worse. The Moore Memorial Public Library writes that the temperature of the hold continued to climb until it was almost 850°F, the temperature at which ammonium nitrate explodes. Fuel was also likely leaking onto the bags of fertilizer, "literally adding more fuel to the fire."

The Office of Response and Restoration writes that around nine in the morning, roughly an hour after workers first noticed the smoke, the ship exploded. The explosion launched the cargo up to 3,000 feet in the air, was heard up to 150 miles away, and was felt up to 250 miles away, according to the University of Houston. And Firehouse Magazine reports that the force of the explosion was so powerful that it even knocked two small airplanes out of the sky.

The blast also caused a 15-foot tidal wave that flooded the entire surrounding area. Most of the nearby buildings were completely flattened, while many others had their roofs and doors torn off by the blast. Meanwhile, dozens of buildings caught fire due to the falling debris from the explosion. A Monsanto Chemical Company plant, which was located roughly 300 feet from the port where the explosion occurred, was also completely destroyed. Jewel Turner, who was 19 at the time of the explosion, recalled the indescribably beautiful colors of the explosion, per Houston Chronicle.

But unfortunately, this wouldn't be the only explosion of the disaster.

Explosion of the SS High Flyer

The SS High Flyer was docked near the Grandcamp and was also loaded with ammonium nitrate. And in addition to the 1,000 tons of ammonium nitrate fertilizer that it was carrying, it was also loaded with 2,000 tons of sulfur. And according to Moore Memorial Public Library, when combined with sulfur, ammonium nitrate becomes more volatile.

Initially, the High Flyer wasn't severely damaged in the explosion and merely started drifting. But the captain, fearing another explosion, ordered for the anchor to be raised so he could steer the ship away from the area. However, the crew was unable to lift the anchor, and the ship continued to drip closer and closer to the flaming remains of the Grandcamp. After roughly an hour of trying to lift the anchor, the crew gave up and abandoned the High Flyer. Before long, the High Flyer also caught on fire and subsequently exploded roughly 15-16 hours after the first explosion, writes the Office of Response and Restoration, around 1:10 in the morning. The explosion was even given live coverage by Ben Kaplan of KTHT news in Houston. "Here comes another explosion, you have just heard it. The sky is like broad daylight."

Interesting Engineering writes that due to the explosion of the High Flyer, the SS Wilson B. Keene was destroyed, and further damage was done to the port. But unlike the first explosion, the second explosion was relatively anticipated.

Burning for days

Witnesses of the High Flyer's explosion reportedly thought that it was even more powerful than that of the Grandcamp. In "The Texas City Disaster, 1947," Hugh W. Stephens writes that the scene was described as "a fireworks display, [where] incandescent chunks of steel which had been the ship arched high into the night sky and fell over a wide radius, starting numerous fires."

These fires affected the nearby crude oil tanks, which burst into flames and led to the fire spreading to other buildings. By the time the sun rose, the black columns of smoke could be seen up to 30 miles away. The fires continued to burn for several days until they either burned out on their own or were extinguished by the few remaining firefighters. It's estimated that the approximately 1.5 million barrels of petroleum that burned up was valued at $500 million in 1947, equivalent to over $6.6 billion in 2022.

And according to Interesting Engineering, because the oil-storage facilities in Texas City had also exploded in the blast, an oily residue was left all over the nearby city of Galveston, Texas, which was 10 miles away. Frank Urbanic, who was a junior high school student in Galveston at the time, remembers watching "an ominous cloud raining tar, oil, and soot on us. In about 30 minutes, the sky over Galveston was completely covered in this black cloud," per The Ringer.

A fire department devastated

When Texas City's volunteer fire department showed up to fight the first fire, they brought four fire engines and 27 out of the department's 28 volunteers, along with the Republic Oil Refining Company firefighting team. Firehouse Magazine writes that as the firefighters started applying water to the hold of the Grandcamp, witnesses noted the unusual color of the smoke that started pouring out of the hold, describing it as a peach or reddish-orange color.

But when the first explosion erupted from the hold of the Grandcamp, all 27 volunteer firefighters there were killed in an instant. "Some of their bodies were disintegrated by the heat and pressure of the explosion. All that remained of their apparatus were piles of twisted metal." Every single Texas City fire engine was also destroyed in the blast.

According to the "Fire Engineering's Handbook for Firefighter I and II" by Glenn P. Corbett, before the attack on the World Trade on September 11, 2001, this was the largest loss of life experienced by any fire department in the United States.

Thousands left homeless

In the aftermath of the Texas City disaster, few homes in Texas City were left standing. John Thames was almost four when the first explosion hit, but he remembers that their house, which was "located less than two miles from the docks, was the only one in the area to survive the blast," per Texas Monthly.

In "Chronicles of Incidents and Response, Vol I," Robert A. Burke writes that over 500 houses were destroyed. And up to 90% of residential homes suffered at least minor damage, if not major. As a result, over 2,000 people, practically the entire town, were left houseless and without shelter. The property loss amounted to over $100 million, equivalent to over half a billion in 2022.

According to "The Texas City Disaster, 1947," the commercial buildings fared a little better than the residential buildings, but up to 10% were deemed unsafe in the aftermath of the explosions.

The deadliest accident in U.S. history

The Texas City explosion was the largest and deadliest industrial disaster the United States has ever experienced to date. Firehouse Magazine writes that at least 500 people are believed to have died as a result. At the Monsanto chemical plant alone, 143 employees numbered among the civilian deaths. At least four students from the local dental schools were even called in to assist with identifying victims through their dental records. But "some believed that hundreds more were killed, but unaccounted for, including visiting seamen, non-census laborers and their families, and untold numbers of travelers."

According to the Moore Memorial Public Library, in the aftermath of the disaster, the high school gymnasium had to be turned into a temporary morgue, and a garage was used as an embalming room, with up to 150 embalmers working. And The Ringer writes that when the bodies of victims were recovered, the staff at the segregated local hospital "frequently could not determine the race of the victims." Wanda Baker, who worked for Texas City Terminal Railway, remembers that "There wasn't anyone in this town that didn't know someone who died or was related to someone who was killed," per The Daily News.

At least 3,500 to 5,000 people were also injured in the explosions. However, some people as close as 70 feet from the Grandcamp managed to survive the explosion. Many suffered severe fractures and cuts from blown-out glass and shrapnel from the ship.

What caused the disaster?

Unfortunately, it's unclear exactly what caused either the initial fire or the first explosion. The Fire Prevention and Engineering Bureau of Texas writes that it's even possible that the fire had been smoldering since the previous day. One theory is that the fire was started by a discarded cigarette, but according to the Texas City Disaster Hearings, the location of the fire couldn't have been reached by a discarded cigarette, and there's no dependable evidence that the fire was started by a cigarette or a person.

Because paraffin, a hydrocarbon product, was put on the ammonium nitrate to prevent caking, the fertilizer was essentially a tinderbox just waiting for the element of heat in order for a fire to start. And as Firehouse Magazine notes, the bags of ammonium nitrate were already noted to be warm when the longshoremen were loading them. And an exothermic reaction "resulting in spontaneous combustion can occur with chemical oxidizers at elevated temperatures."

According to "The Texas City Disaster, 1947," the first explosion may have been triggered by the fuel oil, when the bulkhead between the holds collapsed, "dumping a large amount of fuel oil on the molten fertilizer and setting off the explosion," but this is just a hypothesis. The Moore Memorial Public Library writes that the federal government appointed a team to investigate the disaster, but ultimately the team was only simple to conclude that "conditions aboard the ship were conducive to a reaction of the ammonium nitrate."

The first class-action lawsuit

After the Texas City disaster, at least 300 lawsuits were filed against the federal government by up to 8,485 claimants. According to ABA Journal, these lawsuits alleged that under the Federal Tort Claims Act, which stated that private citizens had the right to sue government officials for damage, the federal government had been negligent, and citizens deserved compensation for their losses.

In order to avoid the repetition of evidence, all 300 cases were combined by Judge T. M. Kennedy in the District Court for the Southern District of Texas into Dalehite et al v. United States, effectively creating the first class-action lawsuit. The Supreme Court later described the combined cases as "a test case" plea for the entire class. According to the "Texas City Disaster Hearings," "of the 8,485 plaintiffs, approximately 1,510 sue on death claims, approximately 988 on personal injury claims, approximately 5,987 on property damage or destruction claims."

"Emergency Management," edited by Claire B. Rubin, writes that Judge T. M. Kennedy found the United States government responsible in a non-jury trial in 1950. He found that the explosion was the result of the U.S government's negligence towards the fertilizer export program and in "failing to give notice of its dangerous nature to persons handling it [or supervising its loading]."

Overturning the decision

However, Kennedy's ruling in Dalehite et al v. United States was soon overturned by the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals at New Orleans. In their ruling, they maintained that the United States government was not liable under the Federal Tort Claims Act due to the exception listed in Section 2680, which reads that the Act may not be applied to a claim that is "based upon the exercise or performance or the failure to exercise or perform a discretionary function or duty on the part of a federal agency or an employee of the Government, whether or not the discretion involved be abused," per Dalehite et al v. United States.

ABA Journal writes that after the ruling was overturned in the court of appeals, the case went on to be heard in the United States Supreme Court. And in 1953, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the United States government, which argued for governmental discretion in addition to the idea that the Federal Tort Claims Act was intended for small-scale accidents rather than hundred-million dollar catastrophes.

The town's recovery

After the Texas City disaster, fundraisers were held for Texas City all over the country, raising thousands of dollars, with celebrities ranging from Frank Sinatra to Jack Benny. According to the Moore Memorial Public Library, so much money was donated that committees were appointed by Mayor Trahan to be in charge of distributing the money. Insurance companies in the area tried to process claims from hundreds of people, but with their offices also having been destroyed in the explosions, they set up makeshift offices.

The Ringer writes that in 1955, U.S. Congressman Clark Thompson, who represented Galveston, sponsored the Texas City Disaster Act in order to make sure that the citizens of Texas City received some sort of compensation. This bill allowed for the judge advocate general of the Army to investigate up to 2,000 claims relating to the Texas City disaster. After the bill was passed, almost 1,400 claims were awarded payments that totaled $17 million. Private insurance claims were also awarded $32 million.

After the disaster, many refineries realized that a centrally-coordinated emergency response system might have helped during the disaster. Refineries in the Texas City area subsequently formed the Industrial Mutual Aid System, in which they agreed to help one another during a disaster. Other refineries in Texas that were in industrial zones soon joined as well or formed their own. Quality control officials also implemented new standards for handling ammonium nitrate.