The World's Worst Industrial Disaster In History

Less than 40 years after an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, the world witnessed what became known as the "Hiroshima of the Chemical Age." Considered to be the worst industrial disaster in human history, the Bhopal gas tragedy, also known as the Bhopal disaster, also remains a stark example of environmental racism in terms of how the American corporation has responded to its victims in India.

Despite the fact that hundreds of thousands of people were affected by a gas leak and the toxic dumping by a pesticide plant, the corporation involved has repeatedly eschewed liability and done everything in their power to ensure that the victims receive little to no justice or compensation. Although this isn't the first time that a corporation has avoided liability, the disparity with which they've addressed issues with American victims shows that the pesticide plant in India was intended for maximum exploitation.

Three decades after the disaster, subsequent generations are still being affected by the toxicity left behind. Meanwhile (per Statista), the corporation who would currently be liable is worth over $63 billion.

The UCIL factory

In 1969, Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL), which was owned by the Union Carbide Corporation (UCC), opened a plant in Bhopal, India to manufacture pesticides. According to "The Bhopal Saga" by Ingrid Eckerman, the pesticide plant initially made the carbamate carbaryl pesticide, known under the brand name Sevin, using imported methyl isocyanate (MIC) from the United States. But after 1980, the plant started making their own MIC.

UCIL was given a license to manufacture 5,000 tons of carbaryl annually despite the fact that UCC officials in Bombay realized that they'd be able to sell only half of that in a year. Arguments were made to build a smaller plant, but the management committee in New York was committed to building a large plant. "The president, the directors and the engineers were obsessed by the idea of creating the most beautiful pesticide plant in India and ignored advice from the man on the ground," writes Eckerman.

But due to droughts, famine, and the ineffectiveness of the pesticides, sales fell past what was expected. Environmental Health writes that in 1984, the pesticide plant was manufacturing only a quarter of its production capacity. As a result, UCIL ordered local managers to close the plant so that it could be sold in July 1984. But when UCIL was unable to find a buyer, they decided to "dismantle key production units of the facility for shipment to another developing country."

Prior leaks at the factory

Within 10 years of opening, there were already numerous warnings regarding pollution and leaks in the plant. The Asian-Pacific Newsletter writes that in 1976, two trade unions sent letters to managers, factory inspectors, and the Ministry of Labor of Madhya Pradesh regarding the pollution in the plant. However, they never received any sort of response.

In 1981, a worker named Ashraf Mohammed Khan at the pesticide plant was splashed with phosgene and died 72 hours later, having subsequently taken off his mask in a panic. Although managers blamed the worker for his death, the workers' union noted that he hadn't been provided with a PVC overall and that the manfunctioning valve was in fact responsible for the accident, according to "The Bhopal Saga." There was also a phosgene leak in January 1982, in which 24 workers were exposed and admitted to the hospital. And apparently, "none of the workers had been ordered to wear protective masks." There was another leak several months later in October 1982, this time of MIC, methylcarbamoyl chloride, chloroform, and hydrochloric acid. Although the leak was stopped, two workers were severely exposed to the gasses and an MIC supervisor ended up with intensive chemical burns.

Over the following two years, leaks in the pesticide plant continued "with frightening regularity." Ramnarayan Jadav, a driver in Bhopal, claimed that gas "used to leak every eighth day and we used to feel irritation in the chest and in the eyes," per "The Bhopal Disaster" (posted at Centre for Science and Environment).

The December disaster

V.N. Singh, an operator of the Bhopal pesticide plant, first noticed a leak of MIC gas around 11 p.m. on December 2, 1984. But after informing Shakil Qureshi, the MIC supervisor, of the leak, he was told that Qureshi would check out the leak after having some tea, reports The New York Times. By 11:30 p.m., residents of the city were already feeling the effects of the gas, but they thought that it was just another regularly occurring small leak. According to "The Bhopal Disaster," "if the company had set off its warning siren then, many could have escaped."

The gas continued to spread in high concentrations, and between 12:30 a.m. and 1 a.m., residents started to wake up coughing intensely and with eyes burning. Environmental Health also writes that around 1 a.m., as the safety valve in the plant gave way, a thick plume of gas was released into the air.

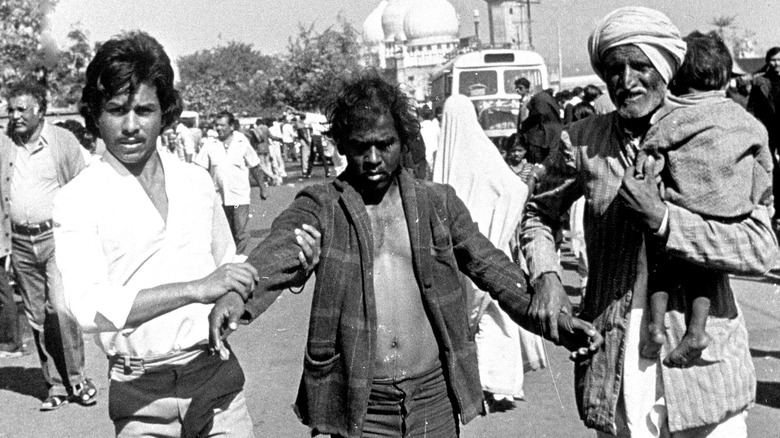

Survivor Champa Devi Shukla recalls the panic as people tried to escape the threat of the misty gas. "The coughing was so bad that people were writhing in pain. Some people just got up and ran in whatever they were wearing or even if they were wearing nothing at all. Somebody was running this way and somebody was running that way, some people were just running in their underclothes. People were only concerned as to how they would save their lives so they just ran," per The Bhopal Medical Appeal.

No one knew what to do

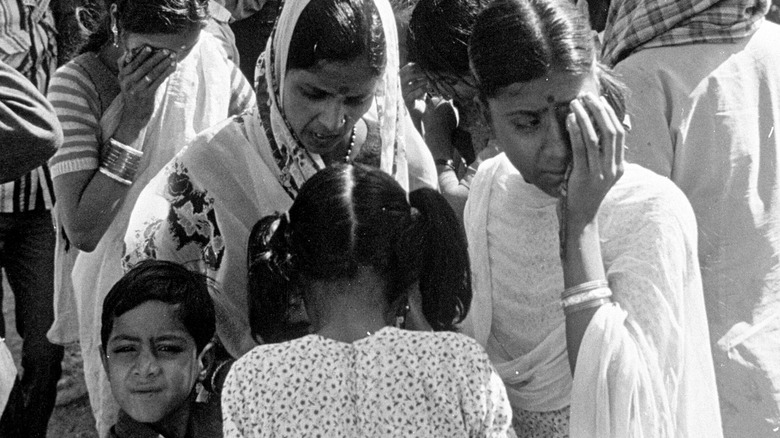

Over 40 tons of toxic MIC gas was released into the air that night. Running and jumping onto whatever vehicle they could find, people tried to flee Bhopal. By 3 a.m., there was a crowded and constant stream of people trying to escape via the main roads. During the mass exodus, hundreds of thousands of people fled for their lives as the gas took over the city. "The Bhopal Disaster" writes that "the panic was so great that people left their children behind, or did not stop to pick up those overcome by exhaustion or the gas." As a result, the streets were soon filled with dead and dying people.

Many tried to find their family members, but were soon blinded by the gas. Eckerman writes in "The Bhopal Saga" that as they tried to shout, their throats became constricted by the gas.

According to The Bhopal Medical Appeal, death due to MIC gas is an incredibly horrific ordeal. Some vomited uncontrollably and started seizing, while others ended up choking to death. Pregnant people who were fleeing ended up miscarrying as a result of the gas. Survivor Rashida Bi later stated that those who managed to escape alive "are the unlucky ones; the lucky ones are those who died on that night." Environmental Health estimates that almost 4,000 people living next to the plant died immediately.

Thousands dead and injured

Although the death toll is disputed, it's estimated that over 500,000 people were poisoned the night of December 2, 1984. According to the Asian-Pacific Newsletter, it's estimated that at least 8,000 people died during the first weeks and over the subsequent decades, it's estimated that there were as many as 20,000 premature deaths as a result of the gas exposure. The Bhopal Medical Appeal writes that many who managed to make it to the hospitals continued to succumb from their injuries, due to the fact that UCC refused to share information on MIC, "claim[ing] the data is a 'trade secret,' frustrating the efforts of doctors to treat gas-affected victims."

Eckerman writes in "The Bhopal Saga" that children under the age of 5 were the worst affected, with a death rate of 33 per 1,000. One of the badly affected neighborhoods, JP Nagar, reportedly lost 25% of its 7,000 residents. It's also estimated that over 3,000 large domesticated animals were also killed or had to be put down because of the gas exposure.

In addition to the staggering death toll, at least 100,000 people ended up with permanent injuries due to the gas. As of 2022, the Bhopal disaster remains the worst industrial disaster the world has ever seen.

What caused the leak?

At the Bhopal plant, water was used to wash out the pipes to keep the filter system clean. But on the night of December 2, 1984, water managed to reach the tank of MIC. According to the Loss Prevention Bulletin, no one knows exactly how the water ended up reaching the MIC tank, but once it did, a chemical reaction occurred that started generating heat. As a result, the MIC tank got warmer and warmer because the refrigeration system had been switched off months prior.

As the tank heated up, it led to a thermal runaway reaction, leading to hot MIC vapor bursting out of the tank and escaping through the "dysfunctional vent gas scrubber." By the time the operator noticed the condition of the MIC tank, "it was already too late to stop the catastrophic loss of process containment. At this point, nothing could have been done to stop the release." However, if any of the safety measures theoretically in place had been functioning as intended, the Bhopal gas tragedy could have been avoided.

The New York Times reports that there were several irregularities at the Bhopal pesticide plant. Not only were internal leaks ignored and rarely investigated, but the shutdown of the refrigeration unit was a violation of plant procedures. In addition, two of the main safety systems had reportedly been inoperable for at least several days, if not weeks, at the time of the gas leak.

Environmental racism

The lack of safety systems, training, or effective public warning of the gas disaster wasn't a UCC characteristic. Instead, it reveals a stark pattern of environmental racism. Unlike the Bhopal plant, the UCC West Virginia Plant used a computer system to monitor plant functions and leaks. But at Bhopal, management "relied on workers to sense escaping methyl isocyanate as their eyes started to water," a practice that violated the orders in UCC's technical manual, according to The New York Times.

The Atlantic writes that although the West Virginia plant was operating at a loss by 1984, all of the safety systems and skilled workers were maintained. But in the Bhopal plant, UCC maintained the plant with minimal safety standards. Even after Ashraf Mohammed Khan died in 1981 and Kumkum Modwel, medical officer at the Bhopal plant from 1975 to 1982, reached out to her superiors to improve safety procedures, the company refused to do anything. "I left because no one would listen to me. I left in utter disgust. This is not the way you run a huge corporate plant handling lethal chemicals. This is how not to do things." Based on the condition and procedures at UCC's other plants, it's clear that UCC was well-aware that this was not how to do things. The Bhopal Disaster also notes that UCC has a reputation of being "particularly lax about health and environmental safety" in non-Western countries.

UCC's deflection

After the disaster, UCC did everything they could to push the responsibility onto their Indian subsidiary, UCIL. According to Environmental Health, not only did UCC claim that the plan was completely built and operated by UCIL, but they also "fabricated scenarios involving sabotage by previously unknown Sikh extremist groups and disgruntled employees." However, this claim was disputed by numerous independent sources.

According to "Challenging The Rules(s) of Law," edited by Kalpana Kannabiran and Ranbir Singh, nine UCC and UCIL officials were charged with causing death by negligence, including UCC CEO and chairman Warren Anderson. However, Anderson was released on bail almost immediately and ended up being "personally escorted out of the city by the then Chief Minister and flown out of the country under the watchful eyes of the then Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi."

UCC also claimed that exposure to MIC wouldn't lead to permanent damage or long-term effects, a claim that was also reportedly pushed by Bhopal doctors and WHO officials as well, according to The Bhopal Disaster, despite the fact that numerous voluntary health organizations, individual doctors, and journalists found hundreds of thousands of people to be affected by the gas exposure. And although UCC discontinued operations at the Bhopal plant, they failed to clean up the site and the pesticide plant continued to leak toxic chemicals and heavy metals into local aquifers. The Print writes that the Rajiv Gandhi government was also criticized for its poor response to the gas tragedy.

The Bhopal Gas Leak Act

On December 7, one of the first lawsuits against UCC was filed in a U.S. court. After several more suits were filed in both the United States and India, the Indian government passed the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act of 1985 in March, which allowed the government to be the sole representative of all the victims of the Bhopal gas tragedy in all legal proceedings. However, the North Carolina Journal of International Law writes that as a result of the Act, up to 6,500 civil suits filed in India were effectively terminated. According to Bhopal: Unending Disaster, Enduring Resistance by Bridget Hanna, the act also "included no provisions for victims to communicate with their sole representative, the government, and no recourse for remedying poor representation."

Although over 100 lawsuits were filed in the United States, all of the legal cases ended up being dismissed or moved to be entirely under Indian jurisdiction after a ruling by Judge John F. Keenan, according to Rutgers University Law Review. With this ruling, Judge Keenan underlined the fact "American courts are for American citizens."

UCC settles

Initially, UCC offered a $5 million relief fund as compensation for the Bhopal gas tragedy, which the government promptly turned down, asking for $3.3 billion instead. Business Standard reports that in February 1989, UCC finally agreed to settle and pay $470 million for damages. Environmental Health notes that this paltry sum is nothing compared to the rate of compensation for asbestosis victims in the United States. Had the rates of compensation been equivalent, "the liability would have been greater than the $10 billion the company was worth and insured for in 1984." Meanwhile, over half of UCC's settlement ended up being covered by their insurance.

The Guardian writes that as a result of the 1989 compensation settlement, some victims saw only 25,000 rupees, equivalent to $326, while other victims received no compensation whatsoever. The Atlantic also notes that "under the terms of the settlement, UCC continued to deny liability for the incident." The settlement included no stipulations for any sort of treatment or economic rehabilitation for the thousands of people who had lost the ability to work as a result of the gas exposure, Hanna writes in Bhopal: Unending Disaster, Enduring Resistance. Comparatively, seven former Indian UCIL employees were convicted of death by negligence. As of 2010, the Indian government had only released $100 million of the settlement to the victims of the Bhopal gas disaster.

Enter Dow Chemical

In 1999, Dow Chemical Company bought UCC for $11.6 billion in stock and debt; the acquisition was completed in 2001. But even after the acquisition, Dow Chemical maintained that their purchase didn't include any liabilities from Bhopal. Sticking to UCC's story, Dow Chemical said that any cleanup responsibility at Bhopal was the responsibility of UCIL, The Atlantic reports.

UCC officials repeatedly refused to appear in Indian courts, despite numerous court summons. Even after Dow Chemical acquired UCC and was issued a notice to appear in court to explain UCC's continued absence, Dow Chemical officials similarly refused to appear in court, according to The Bhopal Medical Appeal. This also seems to occur with the help of the United States Justice Department, who has on six separate occasions neglected to pass on the summons for Dow Chemical, reports The Guardian.

Reuters Events reports that the Indian government asked Dow Chemical to pay $22 million for the cleanup of the Bhopal pesticide plant site, since UCC abandoned the site without doing any cleanup, but Dow refuses to pay and continues to deny any liability or responsibility for the Bhopal plant. It's also noteworthy that although Dow readily paid off an outstanding claim against USS from asbestos workers in Texas, another historical liability of UCC, Dow refused, and continues to refuse, to accept any liability for what happened in Bhopal.

Lingering effects

Although the poisonous cloud of gas dissipated within a few weeks, the toxic effects of the Bhopal pesticide plant can be found in the ground soil and water over 30 years after the tragedy. According to The Economic Times, while the pesticide plant operated from 1969 to 1984, toxic waste was frequently dumped in and around the plant, seeping into the surrounding area, and the site was never cleaned up in any way. India Today reports that up to 25,000 tons of toxic waste was left out in the open, while some was also buried in the area.

The Delhi's Centre for Science and the Environment reported in 2009 that even two miles away from the Bhopal factory, the level of pesticides in the water was found to be "40 times higher than the Indian safety standard," per The Guardian. As a result of the soil and water pollution, many people who weren't even exposed to the gas leak have ended up with health problems, including cancers and reproductive health issues. According to the Pulitzer Center, there's so much poison in the mud that "if you dig there in the evening, you'll be sick at night, you'll get fevers." Although the Madhya Pradesh government has sought to provide clean drinking water since 2004, many of these measures have been too little and too late.

Long-term health effects

Those who managed to survive the initial gas exposure still find themselves suffering from long-term health effects from the gas, despite the fact that UCC claimed that the gas exposure wouldn't result in long-term health effects. The Guardian reports that 30 years after the disaster, the mortality rate for those who were exposed to the gas remains 28% higher than average mortality rates. Those who were exposed are more likely to die from cancer, lung disease, tuberculosis, and kidney diseases. Surviving victims are also 63% more likely to fall ill. Many people also continue to experience high rates of infertility, stillbirths, abortions, early menopause, or disrupted menstrual cycles.

Children born to parents who survived the gas exposure are found to have a range of birth defects at 10 times the incidence at national levels. According to "The Bhopal Saga," it's estimated that between 100,000 and 200,000 people were left permanently impaired by the gas exposure, not including subsequent generations who also ended up affected. It has been suggested that some of the survivors' symptoms may also be aggravated by untreated PTSD.