Thomas Jefferson's Busy Schedule Led To Two Pioneering Innovations We Use Today

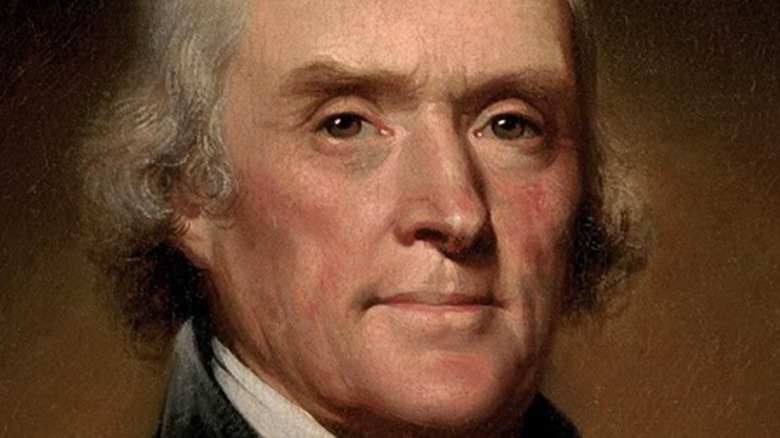

In 1775, Thomas Jefferson had an impressive array of responsibilities. He was part of the Committee of Five, and he drafted the Declaration of Independence at the age of 33. Studious from the beginning, the Virginia-born man was known to obsess for hours a day in college with his books and violin. His dogged nature didn't wane as he rose to political authority, but he was also known to be as shy as he was cerebral, often remaining silent in committee meetings despite his passionate belief in American ideals (via Britannica).

What he lacked in oratory, he made up for in action. After John Adams' requested a draft of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson went to work and produced it in just a few days. As he toiled over the document, he started to notice that his chair was less than comfortable, although he didn't let this impede his progress. Once he was finished, he decided to develop some inventions that would make his work easier, as per Workplace Insight.

The Invention of the Swivel Chair and Writing Box

Thomas Jefferson took his Windsor chair of poplar and mahogany and modified it by adding an iron spindle between the top and bottom half and introducing rollers that he took from a window sash pulley (via Workplace Insight). Together, these additions allowed Jefferson's chair to rotate, much like the modern incarnation so common in office spaces.

He innovated another object that some consider reminiscent of a laptop – the writing box, or portable lap desk. The writing box was designed by Jefferson and was used when he drafted the Declaration of Independence. Although the design was Jefferson's, he had it built by a cabinet maker in Philadelphia. Roughly the size of an average laptop, the box contains a small drawer for paper, pens, and an inkwell, making the invention as compact as a modern writing tablet, as per Smithsonian.

Where Thomas Jefferson's Inventions Ended Up

Thomas Jefferson's swivel chair was passed down to his eldest daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, and then it was gifted to the American Philosophical Society in 1838, thus returning it to its first home in Philadelphia. The chair was later altered by Monticello's joinery, where woodworkers added a new base with bamboo-turned legs and executed significant restorations (via Monticello).

Now housed at the Smithsonian Museum of American History, the writing box was given as a wedding gift to his granddaughter Ellen Randolph's Bostonian husband, Joseph Coolidge, in 1825. Jefferson wrote in a letter to the newlyweds (via Smithsonian), "It claims no merit of particular beauty ... It is plain, neat, convenient, and taking no more room on the writing table than a moderate 4to. volume." Jefferson presciently told the couple that its value would increase with the passage of time, which its acquisition by the museum in 1921 proved. With these notable inventions, the forward-thinking founding father shared, and perhaps even predicted, our modern desire for comfort and reliability.