The Tragic Story Of Sideshow Star Julia Pastrana

When Julia Pastrana died at the young age of 26, she was known as the "world's ugliest woman." Having spent almost her entire life being exhibited, with her death, it almost seemed like she could finally rest in peace. But even when dead, white men continued to profit off of her body. An Indigenous woman from Mexico, Pastrana was exhibited during the 19th century due to the fact that she was born with two diseases that caused her to have hair all over her body and atypical facial features. And even after she died, her body was preserved and exhibited around the world.

The treatment Pastrana suffered in both life and death is unfortunately not unique. Saartjie Baartman's brain, skeleton, and sexual organs were displayed in a Paris museum until 1974. The brain of Ishi, a Yahi man, was preserved and kept at the Smithsonian for almost a century. And after the MOVE bombing, the University of Pennsylvania held onto the bones of several Black children who had been killed in the bombing. This dehumanization follows a racist and colonial ideology that deems the bodies of those cast as others to be public property. And often, it's justified through the idea of scientific exploration, despite the fact that exploration is little more than phrenology.

Ultimately, Pastrana was able to find a final resting place. But it shouldn't have taken over 150 years for her to do so. This is the tragic story of sideshow star Julia Pastrana.

The early life of Julia Pastrana

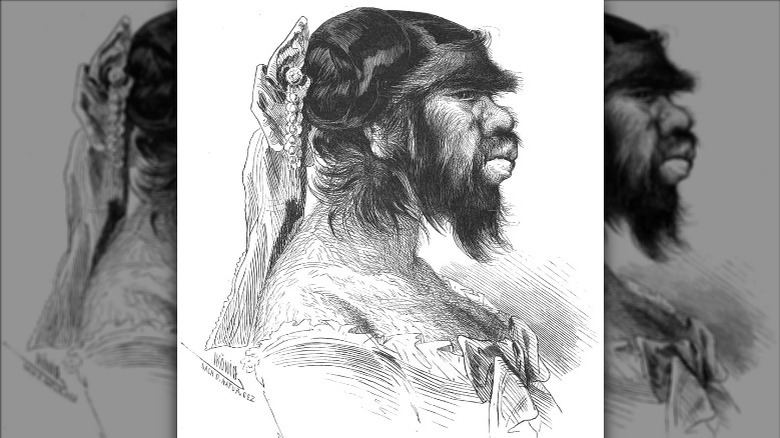

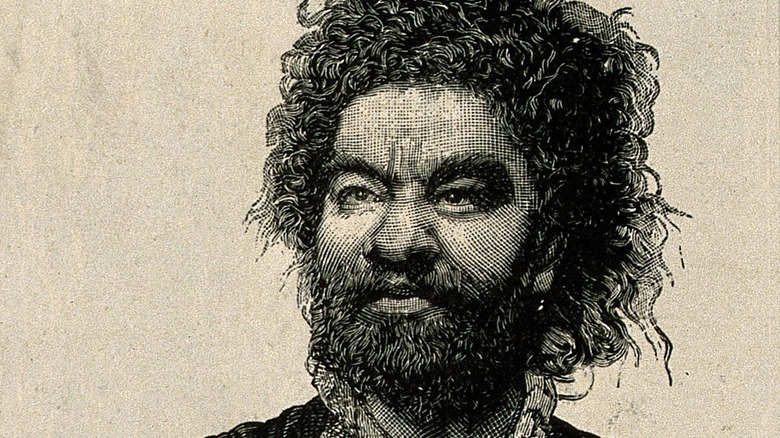

Julia Pastrana was born in 1834 into an Indigenous community in the Sierra Madre in Mexico. There are various stories about her early life, and little is known for certain, but some accounts allege that when Pastrana was born, her mother was worried that supernatural interference had affected Pastrana's features. According to Public Domain Review, when Pastrana's mother saw her for the first time, she whispered the name of the naualli, a breed of shape-shifting werewolves that were often blamed for stillbirths and physical variations in infants. Born with undiagnosed generalized hypertrichosis lanuginosa and gingival hyperplasia, Pastrana had thick hair all over her face and body, as well as thickened lips and gums.

Pastrana and her mother reportedly left their community when Pastrana was very young. After a few years of living in a mountain cave, they were found by Mexican herders, and Pastrana was placed in an orphanage in a nearby village.

Due to her unique looks, as a child, Pastrana became a local celebrity. After hearing about her, NDTV writes that Pedro Sanchez, governor of the state of Sinaloa, decided to adopt her "to serve as a live-in amusement and maid." She ended up working for the governor until she was 20 years old, at which point she reportedly decided to go back to her Indigenous community. However, Pastrana never made it back. Instead, she was taken to serve as sideshow entertainment in the United States.

Sideshow after sideshow

It's unclear exactly how Julia Pastrana became wrapped up in the world of carnival attractions. Public Domain Review writes that on her way back, she met an American showman named M. Rates, who persuaded her to take up a career in sideshows. Meanwhile, The New York Times reports that a Mexican customs administrator bought Pastrana in 1854 and exhibited her as part of his traveling exhibition, explaining that "though slavery had been abolished in Mexico decades earlier, many circus performers were still sold."

Regardless of how she ended up in the United States, Pastrana's debut was in December 1854, at the Gothic Hall in New York City. Wearing a red dress, she sang Spanish folk tunes and danced as the "Marvellous Hybrid or Bear Woman."

Billed as a "Bear Woman from the wilds of Mexico," crowds paid 25 cents per adult and 15 cents per child as they came and gawked at Pastrana's appearance. A contemporary newspaper completely dehumanized her in their description, referring to how "the eyes of this lusus natura beam with intelligence, while its jaws, jagged fangs, and ears and terrifically hideous ... Nearly its whole frame is coated with long glossy hair. Its voice is harmonious, for this semi-human being is perfectly docile, and speaks the Spanish language," per "A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities" by Jan Bondeson.

Countless medical examinations

After Julia Pastrana's debut performance in New York City, many doctors and scientists came forward wanting to examine her. The first doctor to examine her, Alexander B. Mott, declared that Pastrama was half-human and half-orangutan after examining her during a private back-room viewing. Public Domain Review explains that "at the time, orangutans were the biggest and most fearsome primate most Americans knew, [and were considered to be] a symbol of wild, primitive nature and dangerous sexuality."

According to "A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities," Pastrana's exhibition was taken over by J.W. Beach, and with him, she went to several American cities. In Cleveland, she was examined by Dr. S. Brainerd. The doctor claimed that Pastrana was a member of a "distinct species" and, after examining her hair under a microscope, stated that she had "no trace of Negro blood." Even Charles Darwin took an interest in Pastrana, although he never examined her in person. Instead, he examined a cast of her mouth which was supposed to show an extra set of teeth. However, Pastrana didn't have an extra set of teeth, and the confusion involved her thickened alveolar bone, but Darwin still perpetuated this misinformation, per "The Darwin Effect" by Jerry Bergman.

Few of the doctors who examined Pastrana ever asked her questions directly. Almost all would instead direct their questions at whatever showman was exploiting her at the time.

Married and managed

At some point while she was being exhibited, Julia Pastrana met Theodore Lent, also known as Lewis B. Lent, who soon became her manager. Public Domain Review writes that Lent made a lot of money by exhibiting Pastrana, and when P.T. Barnum started taking an interest in her as well, Lent decided to marry Pastrana, likely in order to maintain control over exhibiting her.

According to "The Wonders" by John Woolf, Pastrana and Lent married in Baltimore around 1855. And as Bondeson notes in "A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities," although it appears that Pastrana was in love with Lent, it's possible that Lent married her so that "he could keep control of her and the not unconsiderable earnings," per The New York Times. Considering how Lent went on to treat his wife, his motivation for marrying her can definitely be questioned. However, Pastrana herself once said to her friend Friederike Gossman, a Viennese actress and singer, that "[my husband] loves me for myself."

When she wasn't being exhibited, Pastrana wasn't allowed outside during the daytime, "in case being seen on the street would diminish her earning power," and if she went out even at night, she was forced to wear veils. While advertising her appearance in London in July 1857, Lent distributed a pamphlet that described Pastrana as "always cheerful and perfectly contented with her situation in life," per "A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities."

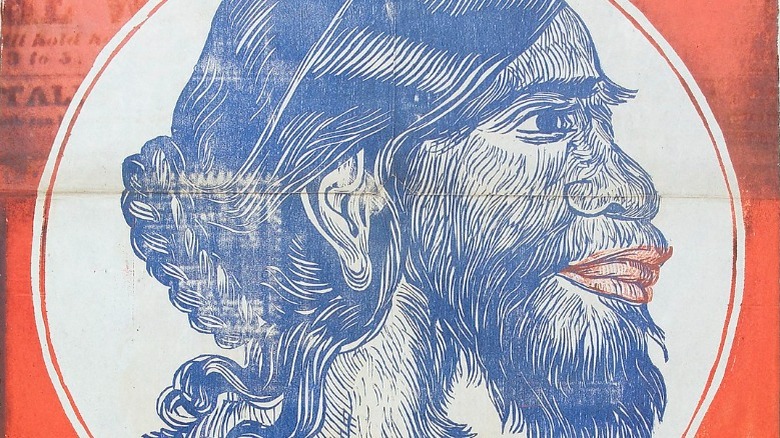

A racialized otherness

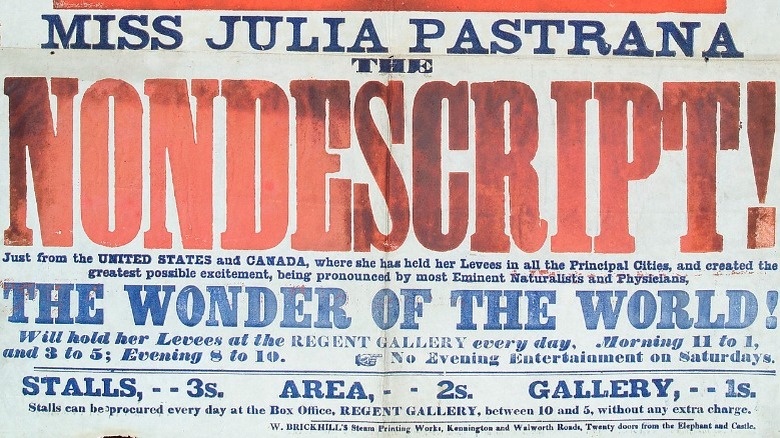

Posters that advertised Julia Pastrana's exhibitions always dehumanized her, referring to her as a bear, a baboon, or an ape. Sometimes, she was described as a "nondescript," which was the word "freely applied to strange animals and monsters from beyond the seas," writes "A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities." Images would also show her with exaggerated features that mirrored the contemporary racist caricatures of Black people, according to Public Domain Review.

"Simianization: Apes, Gender, Class, and Race" writes that "overall, the ape stereotype represents elements of a canon of dehumanization which are 'part of larger verbal and visual metaphoric systems linking the Other to objects or animals.'" Promotional posters of Pastrana would emphasize both her femininity as well as a racialized otherness. Her Indigenous community was referred to as "Root-Digger Indians," and they were described as living in caves and fornicating with animals. Over and over again, pamphlets would imply that Pastrana "was both a symbol of our repressed animal natures and the literal product of sex with beasts."

In 1857, the Standard London newspaper even wrote that Pastrana "is said to be Mexican by birth, but has unmistakable traces of having negro blood in her veins," per NDTV.

A mother in Moscow

In August 1859, Julia Pastrana found out that she was pregnant with Theodore Lent's child. They continued touring with exhibitions, and in the winter, they traveled to Moscow, Russia. There, Pastrana was exhibited at the Circus Salomansky. Public Domain Review writes that Pastrana's child was born in March 1960 in Moscow after what was described as a difficult birth.

Her child was notably large and appeared to have inherited both Pastrana's hypertrichosis and her facial features. But unfortunately, the baby died less than 40 hours after being born. Pastrana soon started running a fever and she died five days later, with the official cause of death being metro-peritonitis puerperalis, at the age of 26. "A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities" writes that Lent even sold tickets for people to see Pastrana while she was on her deathbed. According to Mysterious Universe, Pastrana's last words were allegedly, "I die happy; I know I have been loved for myself," though it's unclear whether or not she actually said this.

Mummifying the bodies

At the hospital, Theodore Lent met Professor Ivan Matveevich Sokolov, an anatomy professor at Moscow Imperial University. Because Sokolov was an experienced embalmer and was experimenting with blending taxidermy with mummification, Lent decided to profit off of Julia Pastrana one last time. And so, according to Public Domain Review, Lent sold Sokolov the bodies of both Pastrana and her child so that he could embalm them and put them on display at the Moscow Imperial University's Anatomical Institute.

Although it's not clear exactly how Sokolov embalmed the bodies, it's known that the process took him six months. And when he was finished, both Pastrana and her child were posed standing up.

But Pastrana and her child ended up being exhibited at the Anatomical Institute in Moscow for only six months. "Interdisciplinary Essays on Cannibalism" writes that once Lent realized how popular the bodies were as an attraction and how profitable they could be, he successfully did everything he could to buy the embalmed bodies back from Sokolov.

Put on display

Even in death, Julia Pastrana couldn't escape being exhibited. After getting the bodies of Pastrana and her child back from Sokolov, Theodore Lent brought them back to London for an exhibition in 1862. Jill A. Sullivan writes in "Popular Exhibitions, Science and Showmanship, 1840–1910" that this time, the price to see Pastrana was just one shilling, reportedly cheaper than it had been to see her while she was alive, but this time she wouldn't be dancing or singing to entertain the crowds. This time, there were no illusions regarding the public's obsession with her physical body.

Public Domain Review writes that scientists continued to offer their opinions on Pastrana's body, this time noting that she looked "exactly like an exceedingly good portrait in wax." And although she was still billed as a nondescript, the headline was altered to read "the Embalmed Female Nondescript." And "Thinking the Limits of the Body" notes that many who came to see Pastrana's embalmed body were those who had seen her live performance just a few years before.

Mysterious Universe writes that after touring with the embalmed bodies of Pastrana and her child for a bit, Lent gave the bodies to a cabinet of curiosities in England. But before long, he was going to be back out on the road with Pastrana and her child, having discovered another person he could exploit.

Pastrana's successor

While in Karlsbad, Theodore Lent learned of another woman, Maria Bartel, who had features similar to Julia Pastrana's. Although Bartel didn't have hypertrichosis like Pastrana, she had enough facial hair that people referred to her as a bearded woman. Lent convinced her father to let him marry her around 1864. According to Public Domain Review, Lent promised never to exhibit Bartel, but before long he was showcasing Pastrana's "little sister."

Having gotten the bodies of Pastrana and her child back from the cabinet of curiosities, Lent resumed exhibiting them, this time with the live Bartel in tow, calling her by the name Zenora Pastrana, writes "The Wonders." And while Bartel danced and sang in places like the Hinné Circus in Warsaw, Poland, the embalmed bodies of Pastrana and her child were presented alongside. As with Pastrana, Lent's relationship with Bartel seems exploitative, with even the press describing Bartel as "Lent's property."

But according to Acta Ethnographica Hungarica, the crowd didn't favor Bartel as much as they did her predecessor. "She was described as ugly, featuring hair on her chin but not on her arms, and not resembling the earlier Pastrana in any way. Her profile and features were considered entirely human and her nose was described as by no means uglier than many others seen for free on Warsaw streets."

Touring Europe for decades

Theodore Lent continued to exhibit Maria Bartel for over a decade as they traveled across Europe and the United States. They eventually retired to St. Petersburg, Russia, where Lent's mental health started to decline rapidly. "At least once, he showed up nearly naked on a bridge over the River Neva, shrieking incomprehensibly, tearing up bank notes and throwing them into the water," according to Public Domain Review. Bartel had him committed to an asylum, and Lent died there in 1885.

After Lent died, Bartel moved back to Germany and sold the embalmed bodies of Julia Pastrana and her child. And for the next 40 years, the corpses were passed back and forth amongst exhibitioners as they were shown across Europe in fairs, circuses, and cabinets of curiosities, writes Mysterious Universe.

In 1921, the embalmed bodies were bought by Haakon Lund, a carnival manager in Norway, who exhibited the bodies in the 1920s with the slogan "Humanity, know thyself." After World War II, the bodies were put into storage, but they were brought out occasionally for small tours, even being exhibited in the United States with the Million Dollar Midways, a traveling amusement park, before being taken back to Norway in 1973, according to Alter.

Public opinion starts to shift

By the 1970s, the public attitude towards the exhibition of the embalmed bodies of Julia Pastrana and her child was beginning to shift. Now when the bodies were brought out for exhibitions, the press responded with outrage. And Public Domain Review writes that in 1973, Sweden banned the presence of the embalmed bodies, "saying corpses could no longer be exhibited for profit." As a result, Lund stopped exhibiting the bodies on tour and put them in a carnival storehouse near Oslo, Norway.

The New York Times reports that three years later, the storehouse was broken into, and the embalmed bodies of both Pastrana and her child were stolen. Although the remains were later found by police in the trash, Pastrana's body had an arm missing, and the child's body was damaged beyond repair.

After being found, the corpses were into storage at the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Oslo and were eventually held in a climate-controlled room. However, Mysterious Universe writes that before long, they were forgotten because nobody knew who retained control over the embalmed bodoes.

Petitioning for repatriation

Julia Pastrana and her child remained forgotten by the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Oslo until 1990, when journalists from the Norwegian magazine Kriminal Journalen discovered her in the basement. And for almost a decade, newspaper articles and government committees argued over whether or not Pastrana should be buried in case scientists wanted to one day study her again. Public Domain Review writes that in 1997, Norway's Ministry of Church, Education, and Research finally decided not to bury her, and Pastrana's embalmed body was moved to the Institute of Basic Medical Science at the University of Oslo

Less than a decade later, Pastrana's cause was taken up by visual artist Laura Anderson Barbata, who was on a residency in Oslo at the time. According to The New York Times, Barbata started petitioning the University of Oslo for Pastrana's repatriation. Although her case was initially refused, Barbata continued to push and even made her case to Norway's National Committee for the Evaluation of Research on Human Remains, who agreed that "it seems quite unlikely that Julia Pastrana would have wanted her body to remain a specimen in an anatomical collection."

However, Jan G. Bjaalie, the head of the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences in Oslo, claimed that the university was open to the idea but they were "not in a position simply to send remains to someone who would ask for them."

Buried in Mexico

In 2012, the governor of Sinaloa, Mario López Valdez, also started petitioning for Julia Pastrana's repatriation. Martha Bárcena Coqui, the Mexican ambassador to Denmark, Norway, and Iceland, also told the university that she would work to accept the body. And The New York Times reports that as a result of this pressure, the University of Oslo agreed to start the process of repatriation in August 2012.

In 2013, Pastrana's body was repatriated back to Mexico, over 150 years after she first left her homeland. Although her body still had bolts and metal rods attached that had been used for exhibiting the body, they were removed and put at the foot of her white coffin. Public Domain Review writes that Pastrana was finally buried near her birthplace in February 2013, with white roses covering her coffin, in a cemetery in Sinaloa de Leyva, Mexico.

According to The Order of the Good Death, during the reception ceremony for Pastrana's funeral, many people came from nearby communities and there were numerous handmade signs that read "No more Julia Pastranas."