What Did People In Ancient Greece Believe About Ghosts?

Ghosts are everywhere. There is not a culture in the world, past or present, that doesn't have something to say about ghosts or hauntings and all the baggage that comes along with it. No matter how they come back or how they interact with the land of the living, the general idea remains the same: The dead return from the grave as spirits. The idea can be found wherever you look, and even if you don't believe in ghosts, it's pretty convincing that so many unique cultures were telling ghost stories long before the concept became global.

So it only makes sense that the ancient Greeks believed in ghosts too. Their stories and fables have lasted centuries because of the profound impact their civilization had on the world in general. From questionable heroes like Perseus to the famous monsters they slayed, like Medusa, these are common concepts that most people have at least heard of. Yet what the ancient Greeks thought about ghosts and the mechanics of their return are not as widely known, despite ghosts being such a big part of their culture. And, as can be expected, what they believed about ghosts shares similarities and differences with what other cultures and civilizations believed. So here's a look at ancient Greek beliefs concerning the return of spirits from the afterlife.

Death in ancient Greece

In order to appreciate what the Greeks believed about ghosts, there are a few things that need to be understood first. One of these is how death was handled in ancient Greece. Like many other cultures, the possibility of ghosts in ancient Greece often stems from funeral practices. As the MET Museum explains in commentary about various works from ancient Greece, the funerary rites of the time were specific and important to the family of the deceased.

They believed that at death, the soul left the body, leaving the remains to then go through the proper rites of burial. As long as the funeral was done properly — and it was an elaborate process — what supposedly happened after death was pretty straightforward. The soul went on the journey to the underworld, to its final resting place among the other deceased, in whatever segment of the underworld they were sorted into.

If the funeral was not done properly or if the person died a premature or violent death, that's when the possibility of ghosts opens up, according to Zocalo. If those elaborate rites were not accomplished, it was a slap in the face of the deceased — which, as many ghost stories hint at, is one surefire way to get a haunting.

The Greek afterlife

The Greek afterlife is well-storied. You're ferried by Charon across the River Styx, past the three-headed dog Cerberus, and handed over to the judges, King Minos, Aeacus, and Rhadamanthus, who would determine where you ought to go (per Encyclopedia Mythica). There were three options, according to World History Encyclopedia: Slain warriors went to the Elysian Fields, good people went to the Plains of Asphodel, and bad people went to Tartarus to work their way up.

That's all well and good, but what makes the Greek afterlife unique is how physically accessible it was. Think about Orpheus, for example. He walked right into the underworld to get Eurydice back. Or Pirithous and Theseus going to steal Persephone from Hades (which didn't go well, by the way). That's a very specific trait of the Greek afterlife. Yes, the underworld was where dead souls went. But mortal souls, if they knew the way, could walk right in and back out again. It wasn't easy, but it was an option.

Any afterlife that is so accessible, that has a physical location and isn't just a nondescript spiritual plain in the cosmos, opens itself up to the possibility of ghosts. Because if mortals can walk right into the afterlife, surely the dead could walk back out too — again, as long as they knew the way.

Greeks and graveyards

Despite the widespread belief in ghosts across cultures, especially ancient ones, the re-emergence of spirits still gets categorized as a paranormal phenomenon, and for good reason. There is a degree of magic involved in the whole idea, a belief in something more than what's right in front of us. The same held true with the ancient Greeks, yet for them, magic was just as accepted, which made ghosts more accessible as well.

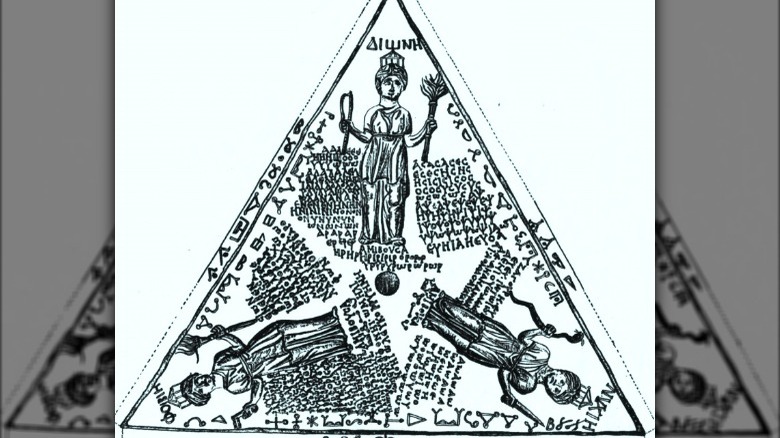

According to World History Encyclopedia, the ancient Greeks had extensive views of magic, and those ideas included everything from enchanted amulets to poisons to evil prayers, spells, and curse tablets. But it's the latter that may be most relevant to their belief in ghosts. Recently, Haaretz reported the discovery of 30 curse tablets at the bottom of a 2,500-year-old well in a graveyard near Athens. These tablets date back to ancient Greece and were dropped there by Greeks attempting to contact the underworld.

According to Haaretz, the curse-tossers hoped the spirits of the dead would take their wishes to the gods of the underworld, where they could then be enacted on whomever the curse was intended for. (Historians believe curse tablets were placed directly in tombs before the practice was outlawed in the fourth century B.C., at which point people started dropping them into wells instead.) In this way, the Greeks treated ghosts as commonplace. They knew they were there, and they were asking them for favors at the one place they were known to be: their earthly resting place.

How ghosts came back

Understanding the underworld and the afterlife of ancient Greek culture is one thing, but the biggest piece of the puzzle is how ghosts could come back in ancient Greece at all. After all, while mortals could conceivably walk right into the afterlife and back out again, ghosts were not always so enterprising as to give that a try. According to Haaretz, it was widely believed that the dead hung out around their graves for at least a while after their death. But to get a full-blown haunting where ghosts were actively participating in the realm of the living, that required something else.

Zocalo breaks down the three ways that ghosts could come back and become a more lasting presence than just the residual post-burial haunting. The first way is quite simple: A person who died a violent death, such as a soldier slain in battle or a victim of foul play, might linger as a ghost. That's where the vengeance factor comes in. If someone was murdered, for instance, the spirit may then seek revenge on the killer. Secondly, a person who died prematurely might become trapped between the world of the living and the dead. Finally, a ghost could come back, no matter the manner of death, if the funerary rites were not properly conducted. Those rituals were, after all, required to see the soul safely to the afterlife. Without them, they were trapped in limbo.

Three types of ghosts

Seeing as how there were three ways that ghosts could come back in ancient Greece, it only makes sense that they were divided into three subcategories of ghosts. The first type, the ataphoi, were ghosts who had not received a proper burial, according to The Collector. The example they provide is Elpenor, the friend of Odysseus who got drunk, fell off a roof, and was never properly put into the ground. That's why Elpenor's ghost later begged Odysseus for a proper burial — so he could finally be at rest.

Then there were the aoroi, who died prematurely and thus had not experienced a full life. According to The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, that could include children, anyone who died without marrying, or anyone who died without raising children of their own. They could often come back vengeful and jealous of those still living their lives. They were even separated from the other dead in Hades since they died without the profound honor of building a family of their own.

Lastly, the biaiothanatoi were any spirits who had died violently, either by foul play or in battle.

The wisdom of ghosts

Ghosts are generally viewed with fear, or at least trepidation. The ghost lore of ancient Greece had that element too, with the possibility of vengeful ghosts coming back if they weren't buried properly or if they died a violent death. That kind of thing can lead to the brand of fearsome hauntings you see on TV today, going all the way back to ancient Greece.

But that wasn't the only way ghosts were seen in the old days. In fact, ancient Greeks believed that the dead held certain wisdom that could benefit the living, and oftentimes they would seek out ghosts in times of trouble and hardship specifically for that reason: the knowledge or wisdom bestowed on them in death. It gave them comfort, according to Zocalo. When a plague hit the Greeks in 430 B.C., while they were already in a deadly war with the Spartans, the Greeks sought the counsel of ghosts for hope in those hard times.

There are also documented instances of people calling back dead relatives to help them find things. For instance, according to the Biblical Archaeology Society (BAS), the Corinthian tyrant Periander called up his dead wife just to ask her if she ever hid any money in life. The BAS also tells of ghosts being able to predict the future. The belief was that the future was essentially prepared in the afterlife, so ghosts knew what was going to happen in the mortal realm before it happened.

The literal gods of ghosts

Not only did the ancient Greeks have firm beliefs about ghosts, but in their pantheon of gods covering all walks of life, they also had a god of ghosts: Melinoe. According to the ancient Orphic Hymns, Melinoe had a very specific purpose, and that was to oversee all offerings and venerations to ghosts. She would ensure that they all got to their intended recipient, making her something of a concierge of all the mortals who had passed into the realm of the chthonic gods.

But she had another purpose too, and it was arguably the more entertaining one, depending on who you ask. The Orphic Hymns mention how, at night, she wandered up to the mortal realm with her posse of ghosts and struck terror in the hearts of all they came across. This adds an entirely different layer to how ghosts could enter the mortal realm. Sure, you could have not been buried properly, or you could just make friends with Melinoe and join her crew.

Aside from Melinoe, there was also Hekate, the goddess of witchcraft, necromancy, and ghosts. This overlap is not uncommon in Greek mythology. According to Theoi, she was a divine figure in mythology who carried two torches and held a certain sway in the underworld, even if it's not entirely clear what her role was. It's even possible, according to Theoi, that Hekate and Melinoe were the same entity.

Ghosts on stage

To see how important ghosts were in ancient Greece, look no further than the stage. The great Greek playwright Aeschylus used ghosts to do practically everything in his work, including moving the plot forward and adding legitimacy to the big knowledge drops that the story was built on, according to Zocalo. In his play "The Libation Bearers," the protagonist siblings Orestes and Electra want to summon the soul of their great father, Agamemnon. In order to do that, they do exactly what ancient Greeks at the time would have done: They went to their father's tomb, poured some libation on his grave, and out popped Agamemnon, ready to counsel the living.

In this case, his counsel helps his children murder a rival, which they otherwise would not have accomplished on their own. This was an established practice that would have been seen as perfectly legitimate by the Greek viewing public. All throughout Aeschylus's writing career, ghosts were major pivot points, often being the key that allowed the protagonists to succeed at their tasks.

And this theme of ghostly intervention was just popular in comedies as it was in dramas (per Zocalo). It was such a big part of everyday life for ancient Greeks that seeing it played out on stage would have fit right into their belief system.

The oracles of the dead

As far as ghosts were concerned, there was no type of magic nearer and dearer to ancient Greeks than necromancy, which is the act of communicating with spirits. In Greek legend, there were four main sites for the oracles of the dead, though there were likely others, according to a paper published in the Classics journal Acta Classica. The four sites were Acheron, Avernus, Heracleia, and Tainaron. Each one was in a rather unassuming location: either a cave or a forest. The job of these oracles was to call up the dead for the living to interact with. When Periander summoned his dead wife to ask her about any possible hidden money, that was done by a necromancer.

Each location had a patron god. It's not always clear which gods were assigned to oracle duty, but assumptions can be made by the nature of certain gods and goddesses. For instance, it was Persephone's job to scatter the shades in the underworld. She had to at least participate in some way in order to funnel the correct spirit to appear at the correct oracle where they were being summoned, according to Acta Classica.

Characteristics of ghosts

Like every other culture in the world, how the Greeks actually perceived ghosts varied widely across instances, from the way the ghosts looked to the terms used to identify them. According to The Collector, ghosts could appear as anything from transparent and pale to opaque and black. There is no central belief that explains the variation, but not even modern paranormal experts can agree on what ghosts look like. According to the Long Island Press, spirits can appear as glowing orbs, full apparitions, or shadows. All of that jives with the discrepancy in ancient Greek ghost stories.

And the naming conventions are no different. While the Greeks used everything from "daimon" to "phasma" to describe ghosts, modern paranormal investigators use terms ranging from "demon" to "spirit," and many more in between.

So while texts vary on their appearance, behavior, and even the words used to name ghosts in ancient Greece, that doesn't detract from the widespread belief that ghosts were real and a part of the culture — just like the variety of appearances and characteristics assigned to ghosts today doesn't cause believers to doubt the presence of spirits.

Ancient Greek ghost stories

Another interesting characteristic of the ancient Greek belief in ghosts is how many of the Greek heroes encountered ghosts and had their paths changed because of it. Odysseus, for example, spent considerable time in the underworld and even learned of his mother's death there, when he encountered her spirit. (When he had gone to consult with the chthonic gods, he didn't know his mother had died.) Odysseus also reported on the variety of shades gathered there, all of whom fit the three general categories of Greek ghosts: those who died prematurely, those whose deaths had been violent, and those who hadn't received proper funerary rites.

Of course, this story is told by Homer and could also be categorized as myth, which is why there are some other snippets of ghostly lore that aren't otherwise widespread in the general belief system surrounding ghosts. For instance, in "The Odyssey," the dead could only communicate with the living after drinking blood, according to The Collector. That very well could be Homer adding a little spice to his storytelling.