The Untold Truth Of Big Ben

It's big. It's bold. It's old. And it tells time. If you don't know what is being described then go take a drive to a large roundabout in central London. There, if you are like the Griswolds in "European Vacation," you will see one of the best-known clocks in the world: Big Ben.

Most people believe Big Ben refers to the large clock tower featured at the northern end of Parliament's Palace of Westminster. But "Big Ben: The Great Clock and the Bells at the Palace of Westminster" notes that this is not true. Actually, Big Ben is the name of the largest of the five bells inside the tower, and what many people call Big Ben is technically called, "The Great Clock of the Palace of Westminster." Further complicating matters, the tower itself was named St. Stephen's Tower until 2012, when it was renamed Elizabeth Tower to honor Queen Elizabeth II on her Diamond Jubilee, according to Britannica.

Because the name Big Ben itself has so many nuances, it would follow that there are dozens of untold truths about it. Let's take a look at the story behind this iconic British landmark.

Big Ben was not the first clock at Parliament

Big Ben is a big old clock, but it is not the first. The first clock tower for Parliament was built in the 1290s. A new chiming clock tower reportedly replaced this tower (and its actual existence has been questioned) in 1367. This medieval clock tower lasted several centuries with Parliament's website stating that it was taken down in 1698 and replaced with a sundial.

There is some gray area in the tower's history, though. In his book, "Big Ben: The Great Clock and the Bells at the Palace of Westminster," Chris McKay notes the demolition date was actually 1707. Regardless, the old clock tower's bell was eventually recast and sent to St. Paul's Cathedral. Meanwhile, Parliament still continued to meet among the different buildings at Westminster, which later became known as the Houses of Parliament. The only apparent trouble was that members couldn't tell time unless they listened for the chimes from St. Paul's.

Big Ben wouldn't have been without a fire

The genesis of Big Ben began in a massive conflagration. According to "Mr Barry's War," a massive fire broke out in Westminster and destroyed most of the buildings on October 16, 1834. After the burning of Parliament, political leaders needed a new headquarters. The next year, a special royal commission was formed with the task of building a new palace for Parliament.

The commission wanted either a Gothic or Elizabethan style design and decided to make it a matter of public competition. There were 97 submissions of which the winner was the architect Charles Barry, who proposed a Tudor-style palace that incorporated the buildings that escaped the fire in its design. Chris McKay explains in his book, "Big Ben: The Great Clock and the Bells at the Palace of Westminster," that after winning the competition, Barry was also charged with constructing the new palace. For this task, he teamed up with Augustus Pugin, who was in charge of decoration.

A competition was held to design Big Ben

Charles Barry originally approached the queen's clockmaker, Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy to design the tower's clock. However, "Big Ben: The Great Clock and the Bells at the Palace of Westminster" explains that the Commissioners for Works thought designing the clock was such a vital task that they didn't want Barry making all of the decisions. Instead, the construction project was thrown out to a competitive bid, and the Astronomer Royal George Biddell Airy was named the judge.

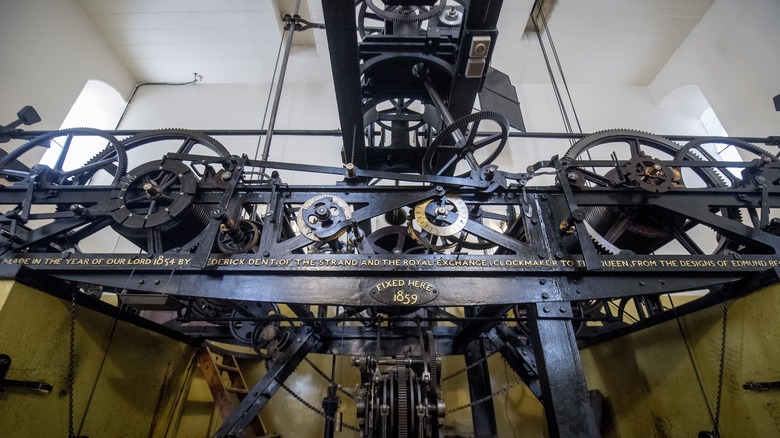

Much like a contemporary request for proposal (RFP), Airy drew up the specifications for the clock. Most important was precision: Airy wanted the hour bell to ring within one second of accuracy. But clockmakers felt this requirement to be impossible considering the technology of the time. So, the amateur horologist Edmund Beckett Denison, who was also engaged as a judge in the process, created a new design. According to Britannica, Denison developed an innovative type of "double three-legged gravity escapement" that helped the clock's pendulum swing with "unprecedented accuracy."

With this design in hand, Edward John Dent, who manufactured chronometers and watches, was selected to construct Big Ben in 1852. Dent had won some renown by winning the 1829 Royal Greenwich Observatory's chronometer contest. Unfortunately, Dent would die a year after being awarded the contract and wouldn't see what would have been the most immense capstone to his career fully constructed.

Big Ben plays an E note

Building the clock mechanism took a couple of years. Parliament says it was subjected to tests for accuracy by using telegraphs to check its time with the Greenwich Observatory, which was considered the world's most accurate timekeeper. The project ordered the casting of four quarter bells and one 14‐ton hour bell. Parliament notes the job of manufacturing this large bell was given to the John Warners foundry, which cast it in August 1856.

But the bell was not quite what was specified. Peter MacDonald explains in "Big Ben" (via The History Press) that it came out two tons heavier at 16 tons, which created problems when shipping it to London and caused damage to the ship when it was accidentally dropped on the deck. Regardless, the ship successfully docked in London and the bell was delivered — finally carted by 16 white horses across Westminster Bridge. The bell produced an E note, which dictated how the other bells were to be cast to make a harmony. (The other smaller bells would play G, F sharp, and B notes, per Parliament.)

According to "Big Ben: The Great Clock and the Bells at the Palace of Westminster," the bell was put on display and struck every day with a large hammer as part of the testing process. It was during this time that people started to call the immense bell "Big Ben" after Sir Benjamin Hall, who was the Chief Commissioner of Works.

The first Big Ben was too big ... or maybe its hammer was

Big Ben is struck from the outside by a hammer, not on the inside by a clapper. But because this Big Ben was heavier than originally intended, Peter MacDonald explains in "Big Ben" (via The History Press) that a 600‐pound hammer was necessary to strike the bell instead of a 400‐pound one. When this first Big Ben was cracked with a 4-foot fracture on October 17, 1857, accusations and opprobrium flew, per MacDonald. The John Warners foundry blamed the heavy hammer, while the horologist, Edmund Beckett Denison, blamed the bell. Either way, it needed to be replaced.

But the truth is, recasting such a large bell was not an easy process, writes MacDonald. Beginning again in February 1858, a large iron ball was repeatedly dropped on the bell from a 30-foot height for two days. As the bell shattered into bits, it was found that there was some faulty metal near the crack. The Warners, however, refused to take the blame. No legal action was taken against the foundry, as public pressure forced them to focus on getting the replacement bell. Finally, the pieces were taken and recast by George Mears of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry into a new Big Ben with very exact specifications on April 10, 1858.

The second Big Ben is flawed

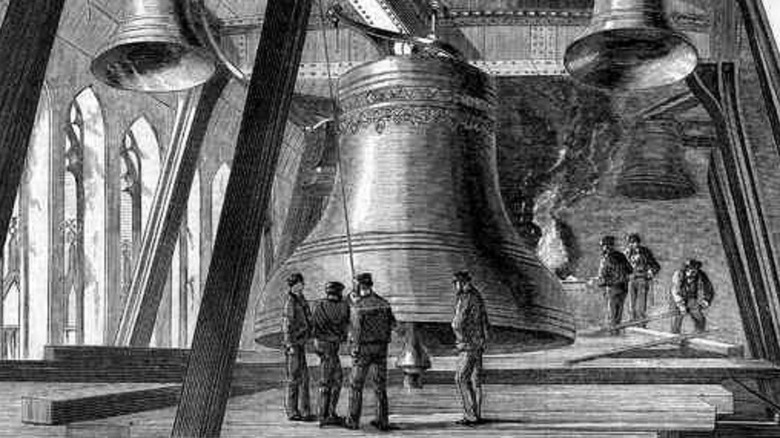

This second Big Ben was lighter than the first, weighing in at about 14 tons. To get it to the belfry in the 314‐foot high tower, Wired explains that the bell was put into a wooden cradle and attached to a 1,800-pound chain. Power was provided by eight men who turned a windlass. The process was achingly slow, but eventually — after 18 hours spread across two days — the men eased the bell up the central tower shaft to the top. After reaching the clock chamber, the bell was turned upright and pulled the final length to the belfry. Once the clock was installed, Big Ben finally rang out for the first time on May 31, 1859. It officially began tolling the regular hours of the day in July 1859.

Then in September 1859, a crack developed. Parliament tells us that Big Ben was temporarily put out of commission, but the smaller hourly bells continued to chime. Since the huge bell was already in the tower, removing it was no easy feat. Instead, Astronomer Royal Sir George Airy came to the rescue again with a way to fix the bell in place. The plan was to turn the bell 90 degrees so the hammer would strike a different spot and cut some of the bell away to prevent the crack from getting bigger. The idea worked, but it is for this reason that Big Ben has its distinct and imperfect tone.

The top of the tower features a light because Queen Victoria wanted it

One distinct feature of Big Ben's tower is the lighting at the top resembling a lighthouse. Officially known as the Ayrton light — named after Acton Smee Ayrton, who was First Commissioner of Works (per Parliament) — tradition holds that the light was installed at the request of Queen Victoria, who reportedly wanted to be able to keep a watch on the House of Lords and the House of Commons. Chris McKay describes in "Big Ben: The Great Clock and the Bells at the Palace of Westminster" that the light was initially powered by a jet of gas but this wasn't sustainable. In 1892, a more permanent light was installed, which initially also used gas but was converted to electricity in 1903.

The BBC tells us that the light has never been turned off since it was installed, other than during both world wars (when it could have served as a glowing bullseye to enemies who wanted to target Parliament) and during restorations that started in 2017.

Big Ben has some big measurements

Being so large, Big Ben and its clock carry some big measurements. Per Parliament, each side of the tower has a clock dial measuring 23 feet in diameter. Within each dial, each one of the Roman numeral hour figures is nearly 2 feet long.

Then there are the huge clock hands. The copper sheeted minute hands are nearly 14 feet long and each weighs over 220 pounds. Curiously, the hour hands — measuring out at around 9 feet each — are heavier. These are made of gunmetal and weigh over 660 pounds. Interestingly, if one were to measure the rotation of the hands as a linear distance, it would come out to about 118 miles traveled in a single year. And finally, to maintain the time of the large clock, Big Ben has a 14‐foot pendulum that weighs about 680 pounds.

To keep the clock going, Esquire explains that the clock is wound three times per week. This is done by turning three winding handles about 2,000 times. Fortunately, they have had machines for the past century which help to automate a process that used to take four hours by hand.

Big Ben is adjusted with pennies

Big Ben's clock is incredibly accurate. Specifically, those who maintain the flat-bed clock mechanism today are required to keep it accurate to two seconds, according to Esquire. When the clock was first installed, this was done by placing timing weights on a shelf at the top of the pendulum, which kept it balanced and on time. However, these weights weren't keeping the clock on time long-term.

So, what is the maintainer of a very big clock to do?

The answer is to use old pennies — specifically, those produced prior to 1971 when British currency became decimalized, according to Reuters. Removing or adding a penny to the pendulum shelf is done to speed up or slow down the clock by 0.4 seconds per day. Esquire points out that over the years, the maintainers have amassed a varied collection of these coins, including a vintage five-shilling coin and a five-pound coin that memorialized Big Ben's 150th anniversary. They also keep a hunk of brass in the tower that can also be used in a pinch.

The worst disaster to Big Ben was in 1976

The clock tower has weathered the years well and managed to survive not one world war but two largely unscathed. However, this does not mean that it is invulnerable to accidents and damages.

Perhaps the worst accident to befall the landmark occurred in August 1976 when metal fatigue in one of the chiming mechanisms made it give way. The resulting disaster was considerable. In "Big Ben: The Great Clock and the Bells at the Palace of Westminster," Chris McKay explains that the one-ton quarter-striking train rapidly fell down the shaft, destroying it. Luckily, the staff overseeing the clock were able to get it running again quickly, though only the Big Ben bell could ring until May 4, 1977. This was just as well since that marked a visit by Queen Elizabeth II for her Silver Jubilee. At last, the bell was able to chime again after eight months out of service.

Big Ben is really blue

By the end of the 20th century, it became clear that Big Ben and its tower were in need of restoration because pollution, the impact of asbestos on the stonework, and the passage of time itself had all taken their toll, per Esquire.

In 2017, Big Ben was shut down and covered with scaffolding, and a team of 500 people got to work, reports The New York Times. Their job was to restore every one of Big Ben's 3,500 pieces to former glory — the first full restoration to ever take place. It is a tough job made tougher by the fact that, as Esquire tells us, there is not really a manual to Big Ben like the one you might find for your microwave. Per Parliament, every piece was removed and taken to the Cumbria Clock Company workshop to be restored out of the public eye. Then, all the pieces had to be put back together again in the correct order.

The restoration has turned up some surprises. One of the biggest was when Parliament had its Architecture and Heritage team look at the original color scheme of the tower's dials. They found that the original figures were not black, but Prussian blue. It is believed that several color schemes were used over the years, with black being adopted at some point to mask pollution. While restoring the clock, they decided to go with the old blue, according to The New York Times.

Big Ben has a delayed reveal date

The reveal date for the restoration project was initially set for 2021, but it was delayed. According to The New York Times, one reason for the holdup was that the restoration team uncovered damages from the Blitz during World War II.

As more time passes, more costs are added to the project. SW Londoner reports the original restoration was estimated to cost nearly $35 million, but the price has since risen to upwards of $92 million. Big Ben and its tower are now scheduled to be completed in 2022, although scaffolding has been coming down since 2021 revealing the clock's makeover.

The restorations didn't please everyone, with some criticizing the costs at a time of economic uncertainty and others critiquing the original color scheme, per SW Londoner. But The New York Times points out that it has been an exemplary restoration job. The project even included some new enhancements including an elevator and a restroom. These must have been of vital importance to the people who maintained the clock, who used to have to slog up and down 334 stairs if they needed to use the loo.