What It Was Really Like At The Cotton Club

If you lived in New York City during the Interwar Period, you probably would have known about the Cotton Club. It was an extremely hip venue with pricey tickets and sought-after performers. Its shiny facade was inviting and it stood as a symbol of modern times. But it was also a Jim Crow-era racially segregated bar that brought a lot of pain to the African-American community of Harlem. As writer Langston Hughes wrote in "The Big Sea": "The Cotton Club was a Jim Crow club for gangsters and monied whites ... Strangers were given the best ringside tables to sit and stare at the Negro customers — like amusing animals in a zoo."

Perhaps more than a fancy venue of the 1920s, the Cotton Club was a big piece of American history. The Cotton Club was built during the Harlem Renaissance, which, as History reports, saw an unprecedented blossoming of African-American art and culture, and an assertion of confidence and independence from white patriarchy. So the club's whites-only policy stood in stark contrast to its location and acclaimed performers, Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington included (via Harlem World Magazine). Let's see what it was really like at the Cotton Club.

It operated during Prohibition

As per History, the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920 banned the sale, production, and transportation of alcohol in the country. Of course, this also meant that clubs were forbidden from selling alcohol to their customers. Prohibition lasted for 13 years, during which organized crime gained control of bootlegging (and became more violent), and moonshine and bathtub gin came to replace other, safer kinds of alcohol. So Prohibition didn't curb alcohol consumption. It just made money for mafia mobs (in Al Capone's case, around $60 million a year).

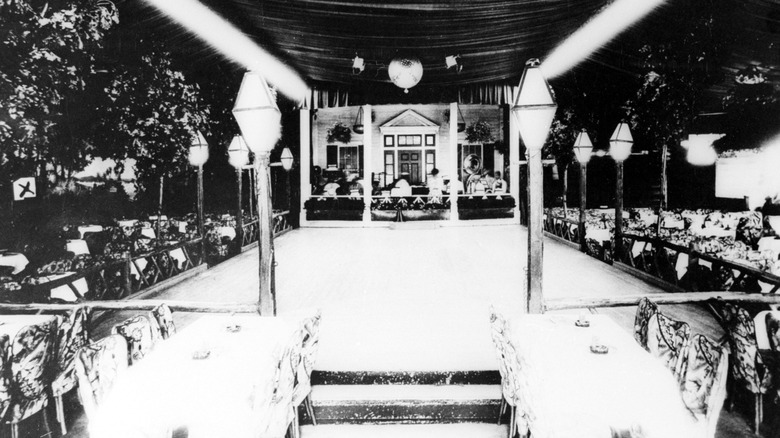

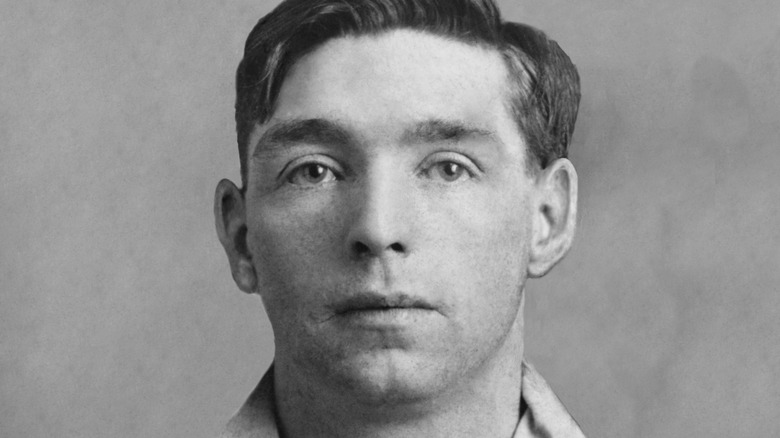

This is the historical context the Cotton Club was born in, as Harlem World Magazine reports. Back in 1920, boxing champion Jack Johnson opened Club Deluxe on the first floor of the 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue building in Harlem. Club Deluxe was an African-American-owned dinner club, just like many others in the area. But three years later, famous gangster Owney Madden bought and expanded the club, renaming it Cotton Club. Madden was a notorious bootlegger at the time, so the Cotton Club became a selling point for his "Number One Booze" (via Vialma Classical). In 1925, the Cotton Club was briefly closed because of this, but Madden made some arrangements with the police afterward, and it didn't suffer any more closures during Prohibition. So if you could manage to attend the Cotton Club, you could probably enjoy a glass of gangster-made beer.

White audience, black performers

As per NYS Music, the Cotton Club was a whites-only venue with African-American performers. In an even more outrageous twist, the club's decor projected racist views, with jungle or plantation themes decorating the walls and stage. According to Wesley Lai's essay, "The Cotton Club: How Black Performers Faced and Confronted Oppression," there are several accounts written by black performers of Owney Madden and white management echoing behaviors from the slave trade. In Dempsey J. Travis' account (via Lai), Madden wouldn't let Duke Ellington leave the Cotton Club unless he paid the entire replacement orchestra.

Other accounts, however, paint the picture of black performers being confident and assertive with the predominantly-gangster whites. And according to musician Cab Calloway (who, as Harlem World reports, led the Cotton Club's orchestra for many years), not even the whites-only policy was that strict. He recalled on "The Cotton Club Remembered": "That wasn't true at all and you see that in the picture ... Blacks could have come to the Cotton Club if they could afford to. We couldn't afford it." As the years passed, the policy became thinner and thinner, until eventually, it was abolished. But during its prime in Harlem, the Cotton Club did predominantly address a white audience, even though the performers were always African-American.

You could have your career launched there

As the 1985 documentary "The Cotton Club Remembered" confirms, there were several big names in jazz whose careers were launched at the Cotton Club: Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, and Josephine Baker, just to name a few. As per Vialma Classical, it was Ellington who first became a prominent figure at the Cotton Club. In 1927, the Cotton Club was already the poshest, most popular venue in Harlem when they hired Ellington to lead the house band. He would call it "the Washingtonians." As per Harlem World Magazine, Ellington's first show was called "Rhythmania," and he performed alongside Adelaide Hall, who would become one of the most famous feminine voices in American jazz. Ellington led the house band between December 4, 1927, and June 30, 1931. During this time, he composed many of his jazz masterpieces, including "Black and Tan Fantasy," "Mood Indigo," and "Creole Rhapsody" (via Britannica). By the time his Cotton Club residency ended in 1931, Ellington was famous worldwide, going on European tours throughout the 1930s.

After Ellington and his orchestra left the Cotton Club in 1931, Cab Calloway took over and became leader of the house band until 1934. As per Financial Times, it was during this time that Calloway wrote his famous song "Minnie the Moocher." Toward the end of Calloway's residence — and the beginning of Jimmie Lunceford's — the Cotton Club had their highest grossing shows and an unprecedented peak in popularity.

You could mingle with the gangsters

According to Vialma Classical, Owney Madden was still in the Sing Sing Prison when he started pulling strings to purchase Club Deluxe from Jack Johnson. By 1923, Club Deluxe belonged to Madden, and it was renamed the Cotton Club, as Harlem World Magazine reports. According to All That's Interesting, it was Madden's idea to address a white audience and to redecorate the club so as to portray the African-American performers as exotic and or savages. He also close to doubled the club's seats, from 400 to 700, and ensured weekly radio broadcasts so as to increase the Cotton Club's popularity and attract rich guests from all over the country.

But Madden wasn't a businessman: He was a gangster, and the club's patrons knew this. As Financial Times reports, Madden was known as "the Killer." Needless to say, he attracted like-minded people to his club. In his autobiography "The Big Sea," Langston Hughes confirms the Cotton Club was a venue for gangsters (and, arguably, their wives). While pictures of famous actors and musicians attending the Cotton Club can still be seen today, those of Madden's friends and foes are more difficult to track. However, the two worlds would famously mingle back in the Interwar Period — after all, there were even people like Frank Sinatra, who embodied both (via History).

You had to be tall to be a Cotton Club dancer

According to Harlem World Magazine, the Cotton Club's Harlem years advertisement for dancers called for "tall, tan, and terrific" girls. But it was a bit more specific than this: female dancers were required to be taller than 5'6" and younger than 21 years of age. Light-skinned black dancers were also the most sought-after, while for male dancers, their skin color didn't seem to matter as much. Famous Cotton Club male dancers, like Chuck Green, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, and the Nicholas Brothers were all invited for their tap and acrobatic dancing skills, not their physique, as per "The Cotton Club Remembered."

But for women, the Cotton Club management was more particular. And once a dancer would be hired, she would have to wear very revealing outfits, as shown by All That's Interesting. But this doesn't mean that female dancers couldn't reach stardom for their impressive skills — two examples are Bessie Dudley and Florence Hill, who often danced to Duke Ellington's fast-paced rhythms. Then there was Lena Horne, who began her dancing career at the Cotton Club and became a world-renowned performer. Despite its strict hiring policies for dancers, Horne remains thankful to the club: "[The Cotton Club] was a great place because it hired us, for one thing, at a time when it was really rough [for Black performers]."

Performances were often risque

The Cotton Club's house bands — most notably, Duke Ellington's and Cab Calloway's — were known for their very fast-paced tunes and, at times, comedic moments. But Calloway took it up a notch, with the myriad of drug references in his songs. As per his own account in the 1985 documentary "The Cotton Club Remembered": "We did things in the Cotton Club — which were fantastic numbers — that were related to dope. 'Kicking the gong around,' 'Minnie the Moocher is down in Chinatown' ... 'Counting millions on the floor when a knock came at the door,' 'nasty old Smoky Joe.'"

The Financial Times does an in-depth analysis of Calloway's famous song "Minnie the Moocher," which is indeed a cautionary tale about substance abuse. Minnie was a woman who fell in love with "a bloke named Smoky / She loved him though he was cokey [took cocaine] / He took her down to Chinatown / And he showed her how to kick the gong around [smoke opium]." Sadly, the song ends with Minnie "pushing up daisies," which is a metaphor for being dead and buried. When asked if his songs reflected the everyday life in Harlem in the 1920 and 1930s, Calloway said there were quite a lot of marijuana street vendors, but didn't share anything about the harder drugs he hints at in his lyrics.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Bill 'Bojangles' Robinson was the most popular male dancer

As Britannica reports, Bill Robinson began dancing when he was 8 years old, as a cashless orphan who was desperate to make ends meet. But by the time the Cotton Club hired him in the late 1920s, he was already a famous tap dancer, known for his incredible ability to run backward 75 yards in 8.2 seconds and for his unique "stair dance." In the 1985 documentary "The Cotton Club Remembered," dancer and singer Adelaide Hall remembers that Robinson, who called himself "Bojangles" at the time, was the most popular dancer at the Cotton Club. The reason is quite simple: "He was unusual, very unusual. He had his moments, but it was a good solo. It really was."

Facts and numbers speak for Bojangles, too. As per Harlem World Magazine, in 1936, he was earning $3,500 a week, the highest salary ever paid to a nightclub performer at that time, and by far the most money an African-American performer had made up until then. However, Bojangles died almost broke, as a result of gambling and an extravagant lifestyle.

Audiences would enjoy music as well as comedy

As Harlem World Magazine reports, the Cotton Club's shows were in fact revues, multi-act theater shows with music, dance, and comedy sketches. Normally, the revues were called "The Cotton Club Parade 19XX," as they only changed once or twice a year. The Cotton Club's very first revue was led by Andy Preer, who joined the club as the leader of the house band in 1923 (the same year Owney Madden bought the club). But not all revues were called "Cotton Club Parades." When Cab Calloway first performed at the Cotton Club in 1930, Duke Ellington was still leading the house band (and thus the "Parades"). So Calloway's first revue was called "Brown Sugar."

Among the most famous "Cotton Club Parades" were the 1933 and 1934 editions, the former featuring already famous singer Ethel Waters and Duke Ellington, who occasionally returned to the Cotton Club after leaving the house band in 1931. The 1934 edition brought a record-setting 600,000 guests. Two years later, the Cotton Club would close its doors temporarily, then move to a new location. But the "Cotton Club Parades" would continue up until the club's permanent closure, as shown by this 1936 performance.

You could see Duke Ellington and Adelaide Hall perform together

Arguably one of the most precious Cotton Club live moments would have been the famous duet of Duke Ellington and Adelaide Hall. As Britannica reports, Hall had already had her first European tour in 1926, after rising to fame with the "Shuffle Along" revue. And in 1927, Ellington had just taken over the Cotton Club's house band when he heard Hall singing (via "The Cotton Club Remembered"): "I was closing the first half of the bill and Duke was taking the entire second half ... I heard him play ["Creole Love Call"] and I was singing and I started humming a counter melody. And he came over to the side of the wing, and he says, 'Oh, Addie, my goodness, that's just what I was looking for.'"

Hall and Ellington went on to record a new version of "Creole Love Call" together, which, as Harlem World Magazine reports, became a hit around the globe. Following this (and several other songs the two recorded together), Ellington and Hall's Cotton Club shows became increasingly popular.

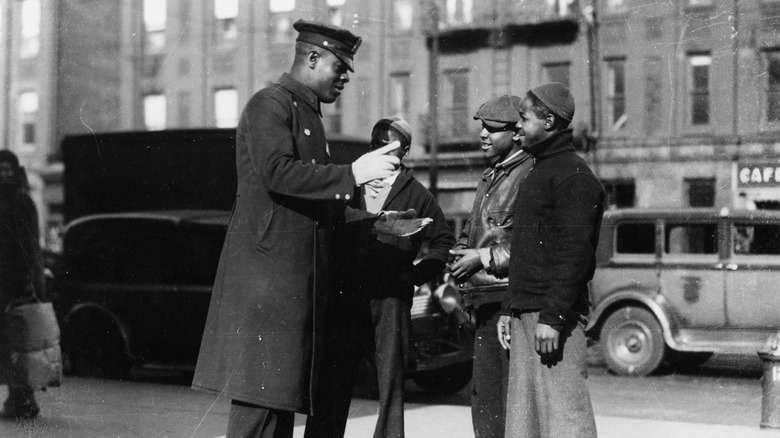

African-American audiences were slowly integrated thanks to Duke Ellington

As Harlem World Magazine reports, once Duke Ellington became a name associated with the Cotton Club, he was made even more famous through various radio broadcasts: WHN, WEAF, and the NBC Red Network starting September 1929. Ellington's increasing popularity gave him compositional freedom — he slowly shifted away from the required "jungle style" and experimented with several new styles, instruments, and orchestral arrangements. Times were changing for African-American performers. But Ellington also wanted freedom for African-American patrons. So he used his stardom and good relations with the Cotton Club's management to help relax the whites-only policy. Perhaps this is why, in Cab Calloway's opinion (via "The Cotton Club Remembered"), there was little to no segregation in place – he simply came after Ellington and his anti-segregation efforts.

Although the changes weren't immediate, Ellington's influence was indeed felt by the Black audiences. In June 1935, the Cotton Club finally began welcoming African-American guests, the first event being a gala organized before a Joe Louis fight.

You could see the first fog effect show at the Cotton Club

The "Cotton Club Parade 1934" was one of the most famous musical revues played at the Cotton Club, as per Harlem World Magazine. Apart from several big names performing (via Overtur) — Adelaide Hall, Leitha Hill, Lena Horne, and Avon Long — the 1934 revue included something never seen before. Indeed, the show featured the first-ever dry-ice machine to create a fog effect on stage. The fog was only created during Hall's performance of "Ill Wind," but it sent waves through the United States.

The "Cotton Club Parade 1934" became the club's highest-grossing show. It lasted for six whole months and it garnered 600,000 customers — the Cotton Club's all-time record. The revue came to an end at the Cotton Club in September 1934, but that was not the end for the show itself. Adelaide Hall and the whole orchestra went on to tour America with the exact same setlist, perhaps with the dry-ice machine as well.

Building tension during the 1935 Harlem riots caused a temporary closure

The Harlem Renaissance was a huge step in African-American culture and in Black pride — as History reports, it paved the road to the civil rights movement. But that is not to say that all Black Harlem residents had a great life. As per Britannica, racial inequality was still a big problem in the 1930s, especially when it came to finding (and keeping) a job. In March 1935, the tensions reached a boiling point after 16-year-old Lino Rivera was arrested for stealing a penknife. Rivera was freed, but some 10,000 people protested against police brutality, destroying a lot of properties in the process.

The Cotton Club was not affected physically, but the club was a heated debate subject when it came to racial injustice, according to Harlem World Magazine. As of early 1935, racial segregation was still in place (it was about to be abolished in June of that year). Writer and Harlem Renaissance patron Carl Van Vechten thus began pushing to boycott the Cotton Club for its racist policies. As per NYS Music, these threats, along with complaints from the Black performers, led the management to temporarily close the Cotton Club. When it reopened in 1936 on Broadway and 48th Street, the Cotton Club no longer had its whites-only policy in place.

After the Cotton Club closed, you could visit other Cotton Clubs

The late 1930s brought a decline in the Cotton Club's popularity and earnings, as Harlem World Magazine reports. Finally, the club decided to close its doors permanently in 1940, after an increase in rent and the threat of Manhattan club owners being investigated for tax evasion. But Cotton Club fans could rest assured, as several "reincarnations" of the club popped up in the following decades across the United States.

First off, there was the Cotton Club Chicago branch, which opened before the main venue. This branch was operated by Al Capone's brother, Ralph. Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong also performed at the California Cotton Club, which was based in Culver City. Cotton Club branches later opened in Lubbock, Texas (1938), Las Vegas (1944), and Portland (1963). All That's Interesting reports that, while many of these branches have since closed, there's still a Cotton Club today in New York City, although it's not as posh or popular as the original establishment.