What Is The Core Of The Moon Made Of?

If you could drill down into the very center of the moon, what would you find? Not cheese, unfortunately, but instead something far more stable and far less tasty. It turns out that the moon has a core not unlike Earth's. The Earth has an inner core that is mostly made of solid iron and a liquid outer core made of iron and nickel, according to National Geographic. The moon's core similarly has a solid inner center and a liquid outer, per NASA. This core is also comprised mostly of iron with a little nickel.

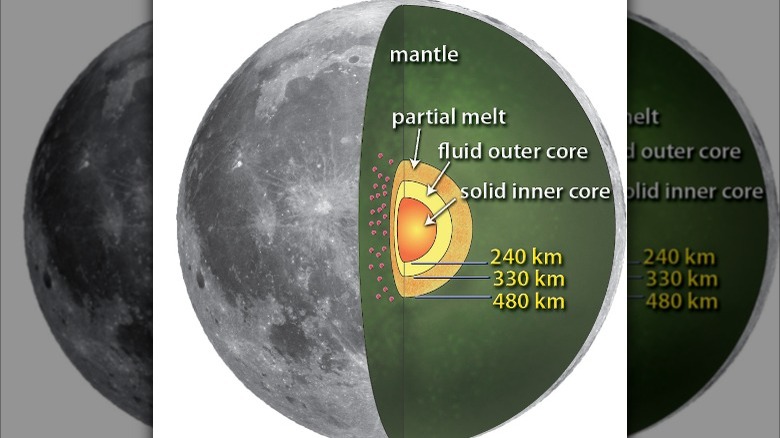

However, there are some key differences between the moon's core and Earth's. One is, obviously, size, both actual and relative. The Earth's core has a diameter of around 4,330 miles, according to National Geographic. Meanwhile, the moon's inner and outer cores combined have a diameter of around 410 miles, with the inner core alone measuring nearly 300 miles across, per NASA. The moon's core also only takes up about 20 percent of its total diameter, while the Earth's core takes up around half. The moon's core also has an added part: a boundary layer that is only half liquid (via NASA).

Layers of the moon

Planetary bodies like the Earth and the moon developed layers through a process called differentiation. When they become hot enough to melt, the chemical components in a planet separate from each other, according to NASA. The heaviest elements, like iron, fall toward the center, and the lighter layers rise toward the top. The moon has four or five main layers depending on how you count: the solid inner core, the molten outer core, the semi-liquid boundary, the mantle, and the crust, per NASA.

The moon's mantle is believed to be composed of either olivine, pyroxene, or both, according to Smithsonian Magazine. It is around 840 miles thick, according to NASA. The crust is much thinner at around 31 miles, but it contains many more elements. It is composed of 43% oxygen, 20% silicon, 19% magnesium, 10% iron, 3% calcium, and 3% aluminum with dashes of chromium, titanium, manganese, uranium, thorium, potassium, and hydrogen thrown in, according to ThoughtCo. It also contains anorthositic plagioclase feldspar, per NASA. Strangely, the moon's crust is thinner on the side we can see.

The Apollo Passive Seismic Experiment

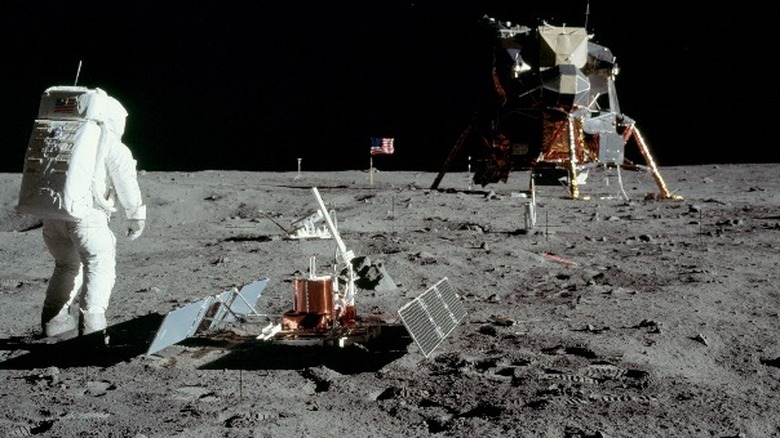

How do we even know what the moon's core is made of? Did we drill inside like Bruce Willis' character did to the asteroid in "Armageddon"? Not quite. Instead, astronauts placed seismometers on the moon during the Apollo missions, according to NASA. These were a series of missions from 1963 to 1972 with the goal of both landing U.S. astronauts on the moon and gathering more scientific data about Earth's satellite, as NASA said further. One endeavor to learn more about the moon was the Apollo Passive Seismic Experiment, which placed four seismometers on the moon between 1969 and 1972 that recorded data until 1977.

The first seismometer was deployed during the Apollo 11 mission that saw human beings walk on the moon for the first time. Astronauts Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong brought it with them during their historic July 20, 1969 moon landing. It actually consisted of four seismometers powered by two solar panels, according to NASA. Because of its power source, it could only record moonquakes during daylight hours. This data would then be sent to Earth. The first model stopped communicating after only three weeks, but more advanced models were installed during the Apollo Missions 12, 14, 15, and 16.

Getting to the core

The Apollo Passive Seismic Experiment provided the first glimpse beneath the moon's crust, but it wasn't until 34 years later that NASA scientists returned to the data to try and understand what the moon's core was made of. That's because the computers of the era weren't speedy enough to draw conclusions from the data, according to Science. Later researchers also had access to new techniques developed by Earth-bound seismologists. In 2011, they finally published their conclusion in Science: the moon had a solid and liquid iron core similar to Earth's "We applied tried and true methodologies from terrestrial seismology to this legacy data set to present the first-ever direct detection of the moon's core," lead researcher and space scientist at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center Renee Weber said in a NASA press release.

How can scientists know this by studying earthquakes, or, in this case, moonquakes? These shakings show up in the form of measurable waves that travel through rocks, Science explained. Researchers could determine the makeup of the core by looking for waves that had reflected off of it. Weber and her team looked at four kinds of seismic waves that traveled in different directions from deep moonquakes in 38 different locations (via Science).

Signal from the noise

One way that more than three decades of technological development helped Renee Weber's team succeed was in separating the signal from the noise. There were so many different signals pinging off the moon's crust that it was hard to isolate the waves that the researchers wanted to study, according to NASA. However, the scientists were able to separate the different pings out digitally through a process called "seismogram stacking."

Their research was bolstered by the fact that another team from the University of Toulouse in France had also studied the moon's seismic waves to determine it had a liquid core of around 227 miles, which is very close to NASA's calculation of 205 miles, according to Science. The French team used a slightly different method of looking at two kinds of waves from just three moonquakes. The studies impressed other scientists as well. "I'm surprised they could get this much information from this data," planetary physicist David Stevenson of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena told Science.

Lunar origins

So why does it matter what the moon is made from? Understanding the satellite's geology can tell scientists how it was formed, NASA pointed out. An example of how the moon's composition can tell us about its origins came from a 2020 study published in Nature Geoscience. Previous analysis of lunar rocks had found that they had a similar mix of two different oxygen atoms to Earth, Smithsonian Magazine explained. However, this clashed with the leading theory of how the moon came to be, which is that it was created in a collision between Earth and another planet called Theia. It would be unlikely for the two planets to have the exact same chemical makeup, and it would also require an explosion larger than scientists believe occurred for them to mix enough to end up with such similar oxygen profiles.

The new research helped resolve this conundrum by separating out rocks from the moon's surface and rocks that came from underground, such as volcanic glass. It turned out, the rocks from closer to the moon's core had an oxygen mix less like Earth's. "The crust is where mixed debris would have ended up, whereas the deep interior would have more bits of Theia," Senior Lecturer in Environmental Science and Planetary Exploration at the University of Stirling Christian Schroeder explained in The Conversation.