Ways Religious Leaders Helped Women Get Abortions Before Roe Vs. Wade

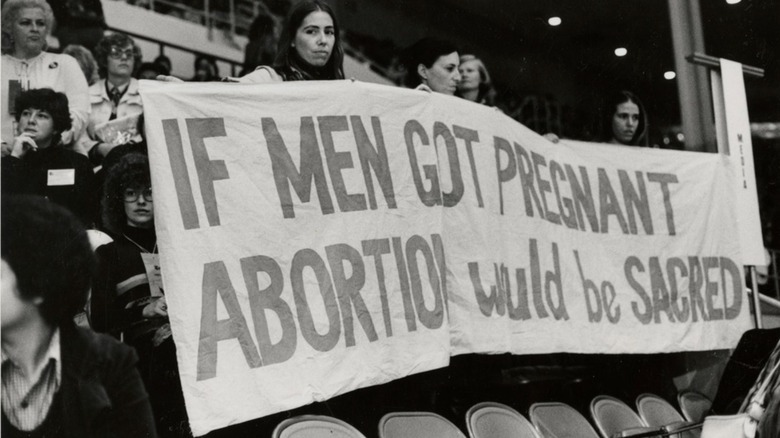

Religious laws are often used to justify the worldwide repression of women, taking away their rights and liberties to live, love, and reproduce according to their free will. Repeatedly, these dogmas do not stem from some universal law or even religious texts but from intentional misinterpretations of those who seek power.

As per Slate, American women didn't have the legal right to abortion before Roe v. Wade in 1973, and many of them died or were harmed during expensive and inaccessible illegal procedures. This did not go unnoticed by groups of religious clergy, who felt it was their moral duty to help these women in need, as well as to lobby for the change in legislation.

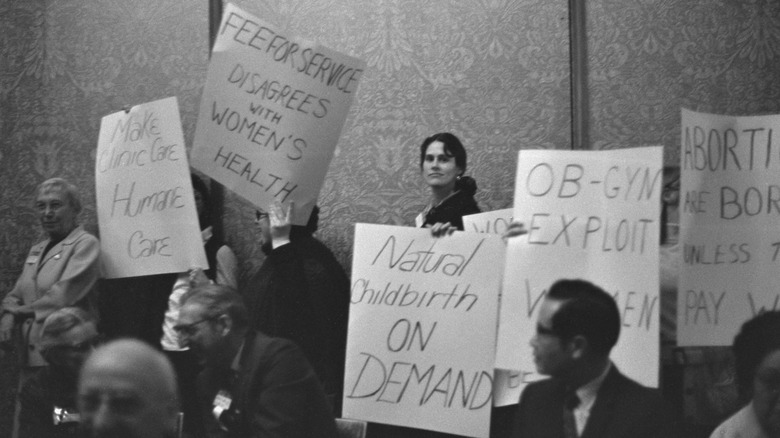

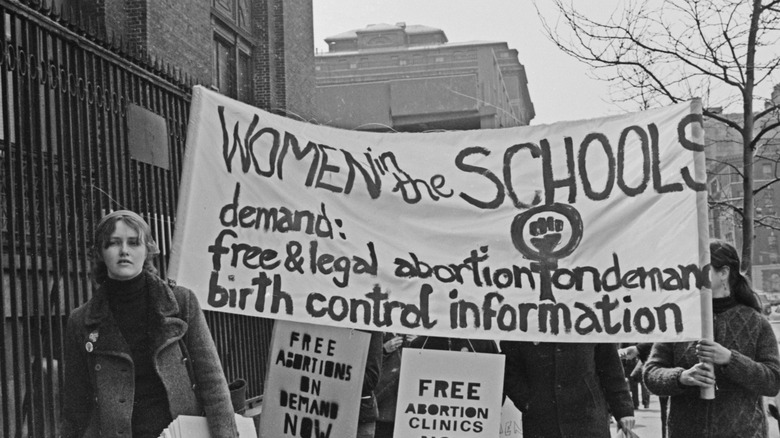

Numerous courageous church leaders publicly demanded better healthcare for women, exposing themselves not only to critics but to criminal prosecutions as well. The core of their work was setting up consultation services all across the country, where women could seek advice, information, and support. The first organization of its kind, the New York Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion was established in 1967, connecting Protestant and Jewish communities, along with a few Catholic nuns. Cleveland Clergy Consultation Service, Chicago Clergy Consultation Service, along with other branches in Florida, Detroit, and other cities followed soon after, helping thousands of women in six years of existence.

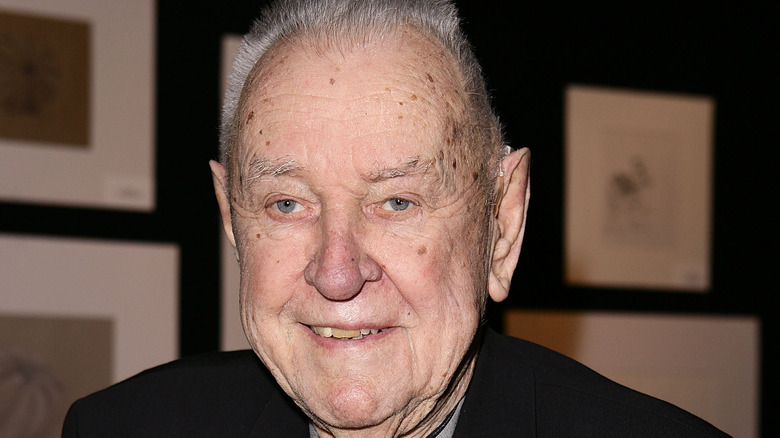

Reverend Howard Moody

The Rev. Howard Moody, born in 1921, was a passionate supporter his entire life of the avant garde and those who were neglected, as per Religion Dispatches. He organized support groups for gay men in the 1980s, campaigned against harsh drug laws, and encouraged freedom of expression.

Moody became a pastor at Judson Memorial Church in Manhattan in 1957 and was soon faced with the reality of an unwanted pregnancy. A single mother of three reached out to him for help in getting an abortion. They went to a provider in New Jersey, who was allegedly connected to the criminal underground, but the provider rejected the pair as they didn't have the secret word. Moody later noted the experience felt horrifying.

The incident led Moody to become sensitive to issues many women were facing, establishing the New York Consultation Service soon after. Believing empathy is the key to understanding, he organized a presentation for the pastorate with a pathology doctor, who explained to the priests the process of an abortion and its effects on a woman's body. By highlighting the physical pain, the doctor made them understand the risks women are willing to go through, despite the law, when they decide they do not want a child. Moody realized the laws on abortion didn't make much sense, claiming that "one can only conclude that abortion was directly calculated, whether consciously or not, to be an excessive, cruel, and unnecessary punishment."

Reverend Finley Schaef

As per Religion News, the Rev. Finley Schaef served at the Methodist church in Queens, New York, in the mid-1960s. He got a visit from a mother and her desperate teenage daughter, who wanted abortion -– the girl got pregnant after her father sexually abused her. At the time, Schaef had no idea how to help them and could only offer a prayer. However, he was left troubled after the encounter and soon came to understand that children should be wanted and conceived with love. "I realized that motherhood should be something that is chosen, not imposed, not just for the sake of the mother but for the sake of the unborn," he said.

When Schaef moved to a different congregation, still in New York, he participated in a gathering where numerous women publicly spoke about their experiences with unwanted pregnancy. After discussing with the Rev. Howard Moody how they could act, Schaef and Moody pulled in other clergy, and the Clergy Consultation Service was born. Schaef, Moody, and other clerics considered themselves a solution to the increasing involvement of the government in women's lives, joining the secular public in combating that abuse.

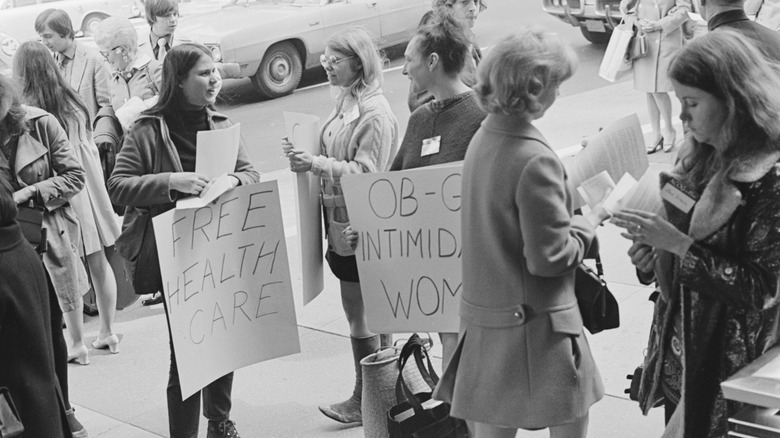

Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion in New York

The Rev. Howard Moody, the Rev. Finley Schaef, and 19 other Protestand and Jewish religious leaders officially founded the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion (CCS) in New York in 1967, officially announcing it in The New York Times. As per The Atlantic, the movement soon spread through the country with the establishment of other branches, and at least 1,400 clerics helped women in the six years of CCS's existence.

The main goal of the organization was providing women with low-cost and safe abortion care. They believed all women should have equal access to the procedure, regardless of race and social status, and the clergy should help them with support and information.

A big part of their interfaith consultation services was the referral program, providing women with a list of providers they had personally checked out. One of the CCS members, church administrator Arlene Carmen, visited the doctors undercover to assess and monitor the quality and cost of abortion providers. CCS also collected reports from women themselves to flag any potential risks and exclude the doctor from the program. Around half a million women used the referral program during its existence, reports Judson Memorial Church. Because cost was often the biggest obstacle in obtaining an abortion, CCS also negotiated the fee for the procedure and excluded doctors from their referral program if they tried to overcharge their patients, notes The Atlantic.

CSS even helped women to travel to London, where abortion was legal. The organization helped women with their itinerary and travel documents, along with selecting the best doctors for them (via History Extra).

Reverend Spencer Parsons

According to the The Journal of Research in American Civilization, the Rev. Spencer Parsons' religious, professional, and political background led him to embrace the ideas of abortion rights. Working as the dean of the University of Chicago's Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, he had a close connection with students but also with the 1960's revolutionary movements of the time.

Parsons and his colleagues used different methods to elevate women's rights. Dr. Lonny Myers, Episcopalian minister Don Shaw, and Parsons established the Illinois Citizens for the Medical Control of Abortion (ICMCA), campaigning for the removal of the abortion ban law in Illinois. Parsons, along with the Rev. Howard Moody, argued for free abortion access at the American Baptist Convention in 1968.

But political action wasn't enough. Trying to help a pregnant student in 1968, Parsons directed her to the underground feminist network Jane Collective. But many more women came asking for help, so Parsons divided his referrals between Jane Collective and the New York CCS, as he knew Moody and his work well. But the demand was just too high, and in March 1969, Parsons established the Chicago Clergy Consultation Service. Working with minister Edgar Peara, they invited 50 clerics from around Chicago and two doctors to lay out the abortion issues and find possible solutions.

They soon renamed themselves the Clergy Consultation Service on Problem Pregnancies (CCSP) in an effort to appease their more conservative constituents. Through their efforts, women were able to receive basic information through a helpline, as well as attend in-person consultations to learn about their options, possible risks, and available providers.

The editorial support

Connected by a common cause, many different members of the church engaged in controversy surrounding abortion access. Some of them ran support networks, while others fought the ideological battles in theological spheres, writing essays and commentaries. Defending women's right to reproductive health and freedom for different moral and philosophical reasons, they all helped to open the discussion and give voice to previously silenced women.

The Christian Century magazine, a prominent religious biweekly led by the Rev. Harold E. Fey, published the editorial titled "Abortion Laws Should Be Revised" in January 1961. The article stated that abortion ban laws were inhumane and extremely punitive and that the decision around women's reproductive health should be a matter of law, medicine, and church, not only the latter. The text appealed for a revision of abortion legislation, starting with relaxing the rules for minors, victims of incest or rape, and women with disabilities.

According to CNN, in 1968 Christianity Today magazine published a unique issue on reproductive rights, presenting affirmative opinions of evangelical intellectuals. One of the contributors was Bruce Waltke from Dallas Theological Seminary, who, basing his argument on the Bible, asserted the position that life begins with birth not at conception. Christian Life magazine supported that claim, stating that according to the Bible, the value of a fetus can't be the same as the value of an adult.

Reverend Robert W. Hare

The Rev. Robert W. Hare's story highlights the risk CCS members put themselves in, reports Slate. In 1969, during his service as a Presbyterian minister in the Congregation for Reconciliation in Cleveland, Hare joined the Cleveland CCS branch since he was a strong supporter of human rights. There, he met a young 20-something teacher who wasn't married, and her pregnancy would cost her a job. In good faith, Hare recommended her to Dr. Pierre Brunelle in Massachusetts. But, due to the demand on CCS services, the organization didn't do its usual vetting of abortion providers in Brunelle's case. Hare was unaware that Brunelle was an extremely bad choice, having been convicted several times for his low-quality abortion procedures. His practice was also under police surveillance at the time, and the police targeted and interrogated many of Brunelle's patients, including the school teacher after she returned home and a college student, while she was still bleeding from her operation.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts charged Hare for "being an accessory to abortion before the fact," threatening him with a fine and seven years in prison. Several Jewish and Protestant leaders in Massachusetts and Ohio defended Hare, as well as Brunelle, both in the courtroom and the court of public opinion. Eventually, Brunelle was sentenced to four to six years in prison (he served 16 months, according to the Boston TV News Digital Library), while Hare's criminal case was dropped after the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision.

Bishop James Pike

James Albert Pike Jr. had quite a reputation, partly due to confrontations he had with the church but also due to his scandalous personal life, full of alcohol and women, as reported by The New York Times.

According to Encyclopedia, Pike was arguing for a broader and more liberal discussion of institutional religion, which he often saw as outdated and rigid. In 1952, he became the dean of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City, advancing to the bishop position of the Diocese of California in San Francisco. Pike fought for women's ordination into the church order but also expressed his opinion on worker's rights, the death penalty, and anti-Semitism. His beliefs led the Episcopal House of Bishops to call for a heresy trial in 1966, labeling his theological perspectives as offensive, although an actual trial never took place, a per "A Passionate Pilgrim: A Biography of Bishop James A. Pike," by David Robertson. However, Pike was formally denounced by the Episcopal Church.

As a passionate believer in women's rights, Pike wrote several texts on the topic of moral, ethical, and religious aspects of abortion and birth control. Along with other material, he published a paper titled "Abortion: The Freedom To Be Responsible" in Medical World in 1966 (via Syracuse University). He publicly stated that women are free moral agents, as per History Extra, so the decision to carry a child is theirs and theirs only.

Reverend Charles Landreth

As a member of First Presbyterian Church in Tallahassee, the Rev. Charles Landreth joined the Florida CCS branch, where he led a legal battle against Florida's strict abortion legislation, explains Time. After conducting consulting services under the frame of CCS institutional support, Landreth's position became jeopardized, as his activities left him open for attacks from state senators and district attorneys.

As in the case of the Rev. Robert W. Hare, some CCS members and their associates were prosecuted on the basis of aiding women in getting the illegal procedure, as laws prohibited any distribution of information on abortion or any other support. For this reason, Landreth and the Rev. Leo Sandon, fearing the conviction themselves, filed a lawsuit in 1971. The goal of the lawsuit was to counter the laws that enabled such prosecution, by excluding the CCS organization and its members from such cases.

While their case was dismissed, the lawsuit was an important contribution to a wider discussion about abortion in Florida. The court did not judge whether Florida's abortion statutes were unconstitutional in the case of Landreth and Sandon, but it did in others, concluding they were ambiguous and ill-defined.

Reverend Carl Bielby

The Rev. Carl Bielby was the director of social services for the Detroit Council of Churches, who coordinated the foundation of the Detroit CCS branch in 1968, explains Time. At the time, abortion in Michigan was only allowed when pregnancy endangered a woman's life. Same as its sister institutions, the Detroit CCS organization provided women with an automatic helpline, through which they could book a meeting with one of the ministers. The ministers came from different Protestant denominations across the country. But as Bielby told Time, the Detroit CCS branch didn't have legal troubles like some of their counterparts. On the contrary, its activities took place with the "silent acceptance" of the government. The legal prosecutors would only open a case if a woman who used services wanted to press charges against a cleric, as even policemen used the CCS services themselves.

In 1968, Bielby publicly fought for women's right to abortion in court, speaking in the name of the Michigan Council of Churches. He claimed that "as a matter of human right, each woman be given the control of her own body and procreative function, and that she has the moral responsibility and obligation for the just and sober stewardship thereof" (via Time).

Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice (RCRC)

After the law on abortion changed with Roe vs. Wade in 1973, the CCS transformed into the Religious Coalition for Abortion Rights (RCAR). The intention of the organization was to protect women's recently acquired constitutional rights, and throughout the years, many specially designed programs were created to support women's needs (via RCRC). Fighting the continuous oppression of poor women and women of color was always a priority to CCS, and out of this work grew projects like the Women of Color Partnership Program (WCPP) focused on Black women's issues, and The Agenda for Native Women's Reproductive Rights. RCAR was renamed the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice (RCRC), to better mirror the variety of its religious communities.

The CCS advocated for safe, comfortable, and supportive spaces where women could receive abortions, the opposite of cold hospital environment, as per The Atlantic. After abortion became legal in New York in 1970, the CCS opened an abortion clinic, Women's Services, partnering with Dr. Hale Harvey and clinic manager Barbara Pyle. A big emphasis was put on making abortion financially accessible to all, although maintaining the high quality of services.