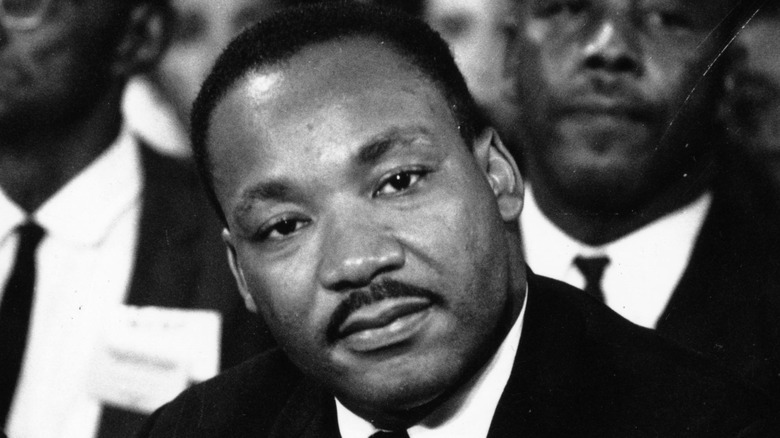

Martin Luther King Jr And Stokely Carmichael's Relationship Explained

For better or for worse, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. has become the name most associated with the civil rights movement in America. He gave impassioned speeches, organized boycotts and marches, and generally was seen as the focal point of the campaign. In fact, King was one of dozens of people involved in the movement, with varying degrees of public exposure. Further still, the men and women who fueled the push for civil rights didn't all agree on how best to carry out their goals. For example, King was steadfastly committed to nonviolence, according to the King Institute. However, other civil rights leaders, particularly of the latter portion of the movement (after the Montgomery bus boycott, as historian Peniel Joseph describes it to NPR), such as Malcolm X, saw violence as an option.

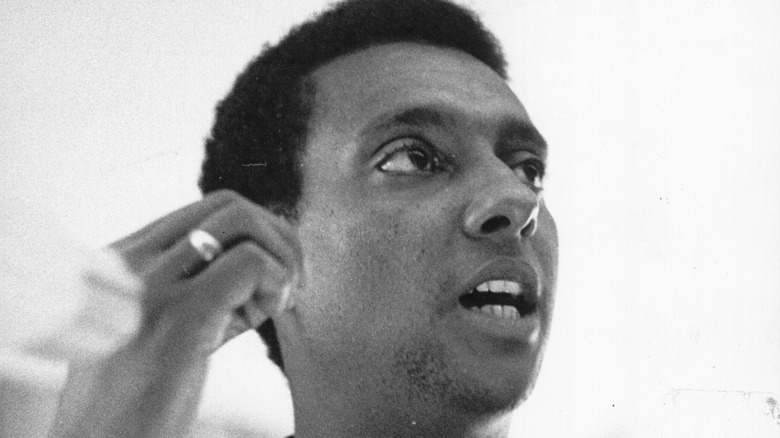

Stokely Carmichael is described by Joseph as a sort of bridge between the philosophies of nonviolence, espoused by King and others, and the "by any means necessary" (to include violence) philosophies espoused by Malcolm X and the like (via PBS Newshour). Despite their differences in philosophy and approach, however, Carmichael and King were fast friends, and Carmichael was devastated when the activist w as assassinated and believed that King's death would invoke violent uprising.

Who Was Stokely Carmichael

Stokely Carmichael was born in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad in 1941 and moved to New York at the age of 11 (via King Institute). He was educated in elite schools and eventually enrolled at Howard University, where he majored in philosophy. Carmichael was front-and-center in the early stages of the civil rights movement, including by helping Blacks register to vote in remote rural areas such as the Mississippi Delta region — at great personal risk. "Stokely was a day-to-day organizer. He was a student activist. He was in Mississippi, in Alabama, so he's a very unique individual," said Peniel Joseph, via PBS NewsHour.

Though at first he was seemingly committed to nonviolence — such as by being chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee — by the later years of the movement, he had begun to embrace "Black Power." And although the phrase also found purchase in the more-violent corners of the movement, Carmichael didn't buy into it full tilt. "Black power for Stokely meant political self-determination. It meant that black sharecroppers, people like Fannie Lou Hamer from Mississippi, were going to be political leaders in a new world order," Joseph said (per PBS NewsHour).

After King's assassination, Carmichael continued his activism, eventually moving toward Black nationalism. Eventually, he changed his name to Kwame Ture and moved to Guinea, where he worked with African leaders toward African liberation and Pan-Africanism. He died of cancer in 1998 at the age of 57 (per King Institute).

Carmichael And King

Though they were compelled by competing ideologies — at least, later in Stokley Carmichael's life — Marting Luther King Jr. and Carmichael were good friends, according to Peniel Joseph (per PBS NewsHour). They certainly had their differences, however, but King kept his opinions to himself rather than expose them publicly. The King Institute notes that King didn't want to publicly oppose the Black Power movement, he later admitted that there was a disconnect between the more-violent wing of the movement and the peaceful wing.

One issue on which the two men did see eye to eye, however, was the Vietnam War. Both King and Carmichael steadfastly opposed the U.S.'s involvement in the conflict. Carmichael was in the room when King delivered a fiery sermon opposed to the war and gave the preacher a standing ovation when he concluded. "There is something strangely inconsistent about a nation and press that will praise you when you say be nonviolent toward Jim Clark, but will curse you and damn you when you say be nonviolent toward little brown Vietnamese children," King said (per King Institute).

As History notes, Carmichael was devastated when King was assassinated, and indeed, he predicted violence in the wake of "white America's biggest mistake." In fact, there were riots afterward, according to a companion History report.