The Lost Oceans Of Mars

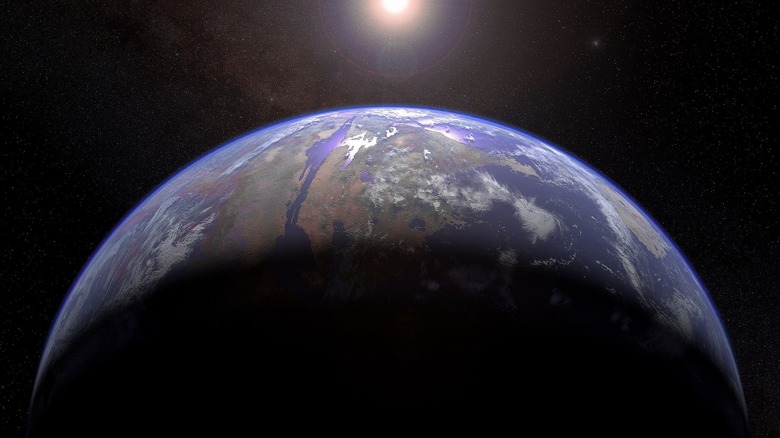

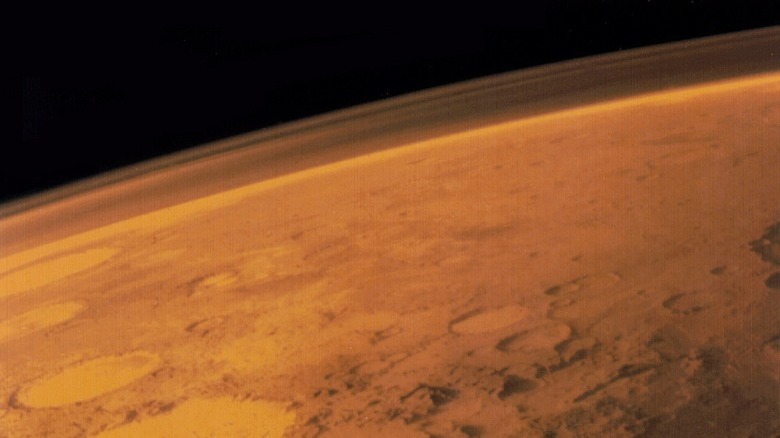

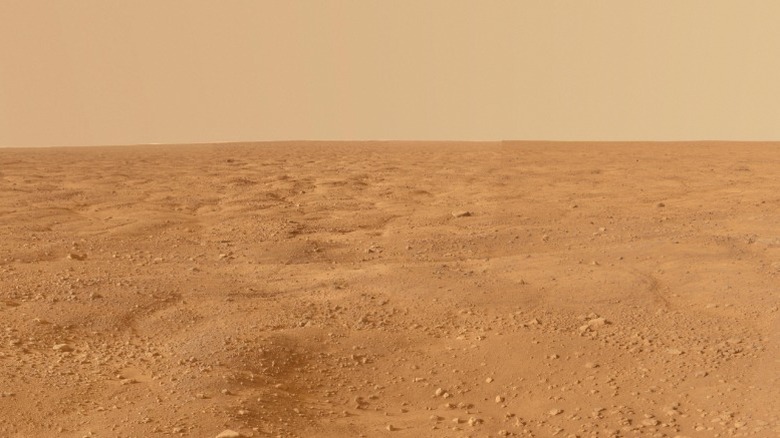

Mars, the planet next door, is famous for being a desolate place filled with endless plains of barren, butterscotchy dust. It's a frosty little planet, with temperatures that would make Siberia feel like a summer vacation spot. As well as being so cold, Mars is arider than the driest of Earth's deserts, with seemingly not a drop of water to be found anywhere on its surface. But it hasn't always been this way, and it wasn't so different from Earth once. Like planet Earth, scientists have divided the history of Mars into geological eras to examine its history. As ESA explains, modern Mars is in the Amazonian period, with so little atmosphere that surface water evaporates instantly. But in the distant past, during the Noachian period, the little planet was likely home to oceans of water.

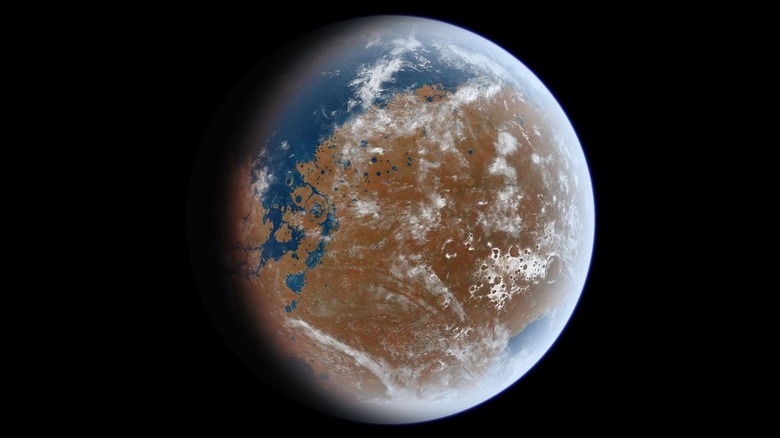

There's an increasing amount of evidence to suggest that dusty little Mars once had a much more comfortable climate and, per Science Daily, an ocean may have once covered much of its northern hemisphere. At some point in its history though, catastrophe struck. Somehow, Mars lost a vast amount of water, as ESO highlights. Which poses some questions: How exactly did Mars lose its ancient oceans? And how much water could still be hiding somewhere in our neighboring world?

Evidence of ancient oceans

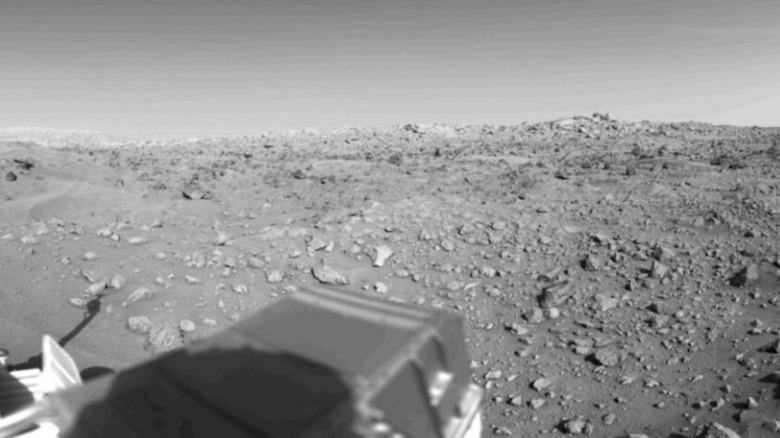

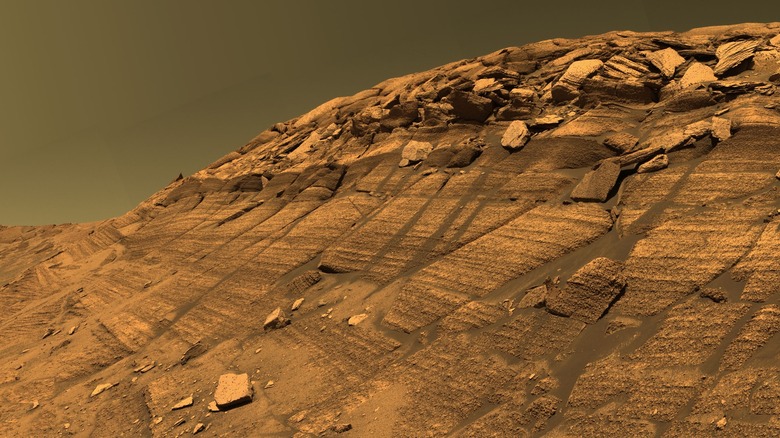

Planetary scientists detected evidence of water relatively early on in the history of Mars exploration. As a study in Nature notes, the first glimpses of an ancient, watery Mars came when the planet was visited by NASA's Mariner 9 space probe in 1971. Among the details it picked out on the surface of Mars were landscapes sculpted by water, some of which appeared to be caused by gargantuan floods in the distant past. NASA's Viking 1 craft would touch down on the Martian surface soon afterward in 1976, and recent studies suggest that the barren, rock-strewn plain where it landed was itself shaped by enormous tsunamis in the distant past. Poor Mars, it seems, has had a violent history.

Mars has all the signs of a planet that used to have a lot of water on its surface, leading scientists to hypothesize what it might once have been like. In 1987, at the MECA Symposium on Mars, John Brandenburg formerly proposed the idea of a "paleo-ocean," which is essentially a huge body of water that would have covered much of the planet's global north back when it was still young. Brandenburg posited that, as the oceans began to freeze, aquifers along the shoreline would release their water onto the surface, causing tumultuous floods which left their indelible mark on the landscape. This seed of an idea would grow into decades of studies centered around water on Mars, both in the past and the present day.

Oceanus Borealis

The ancient Martian ocean is sometimes known by the name Oceanus Borealis. However, as Arizona State University's Red Planet Report notes, it's still a contentious idea in some communities, and scientists have long debated whether or not it truly existed. To try and settle the argument, spacecraft visiting Mars have steadily been gathering data, and there's now a lot of evidence for the ancient ocean, including what may be sediment deposited by water long, long ago.

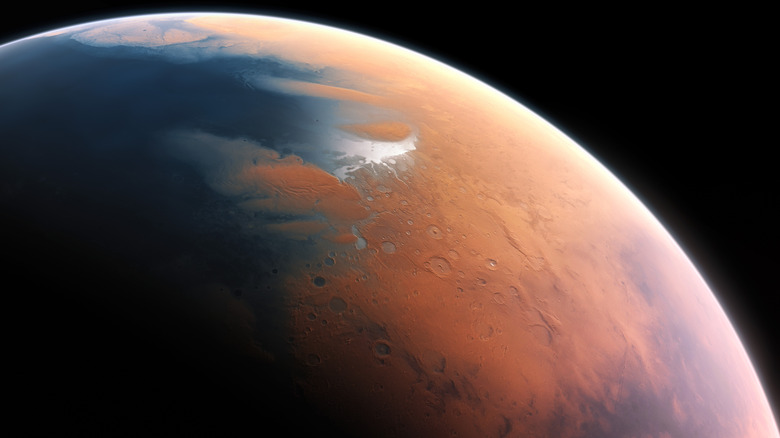

Earth and Mars are planetary siblings, and it's likely they both started life very similarly: as warm and watery worlds. A study published in Icarus finds evidence supporting this, mentioning that for the first billion years after it formed, around a third of Mars' surface may have been covered by water or ice, and it's logical to assume all of this water would've taken a long time to disappear. Because the northern half of Mars is nearly all at a noticeably lower elevation than its south, there's no question that this would've been where Oceanus Borealis lay. This impressively sized ocean, Science Daily notes, would've been proportionately larger than the Atlantic ocean here on Earth, reaching about a mile deep in places. Most of the water on Mars today is frozen in the planet's ice caps, but scientists can use isotope ratios to calculate that Mars once had at least 6.5 times as much water as its ice caps now carry.

The ancient Martian climate

Water simply cannot exist on the surface of Mars today. At least, not for long. According to a paper from the 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, liquid water can persist for a brief period even without an atmosphere, but it will always evaporate under low pressure or freeze in the cold. So for Mars to have had oceans, it would've needed to also have had a much thicker atmosphere than it has today. And it probably did, for a time. A study in the Journal of Geophysical Research finds that ancient Mars could have once had an atmosphere almost as dense as Earth's. Acting as a blanket, it would've kept the young planet warm too, provided it contained enough carbon dioxide to trap heat from the Sun.

The climate of early Mars was very likely warm and wet. A paper published in Icarus explains how it could possibly have stayed this way for as much as a billion years, provided there was a steady supply of carbon dioxide to keep it replenished. Carbonate minerals being burned up by volcanoes on the young planet may have been a good source for this. However, as Space.com explains, some scientists think this means the early Martian climate was a lot more variable, often cold, but with occasional warm periods. If this is true, any ancient oceans would have repeatedly thawed and frozen over!

Tracing long-lost coasts

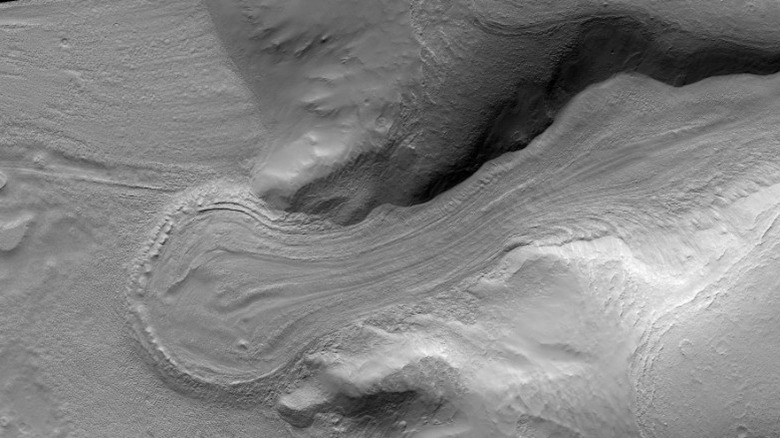

Any sea has a shoreline, and that can leave a permanent mark on the landscape. The telltale signs of these marks can be spotted by geologists, and several traces of what may be an ancient coast have been found on the surface of Mars. One of the most recent, and most compelling pieces of evidence comes from researchers at Penn State University. Using detailed maps from NASA data, they analyzed the surface of Mars using stratigraphy, the study of how water moves and deposits sediments. On Earth, this process forms beaches and sandbanks. On Mars, it left telltale signs of not just an ancient ocean but dramatically changing sea levels, in a region known as Aeolis Dorsa.

This study finds that this long-lost Martian coastline dates back to approximately 3.5 billion years ago, which is a lot more recent than some estimates of when Mars was a more watery place. As detailed by ESA, the Noachian period of ancient Mars ended around 3.7 billion years ago, meaning that the ancient oceans our sibling world used to bear persisted into its next era, the Hesperian period. But this chapter of Martian natural history is a turbulent one. The Hesperian was a catastrophic epoch, during which the Martian climate dramatically changed.

When the seas turned cold

Like on Earth, the Martian geological periods are defined by how the planet's climate changed, and after the end of the Noachian period, Mars changed drastically. According to a paper in Scientific Reports, this change was sharp and sudden (geologically speaking). The warm and balmy days of early Mars were gone, replaced with a cold, dry climate that would eventually become the Mars we know today. Surface water froze, leaving remaining liquid as aquifers below ground, pressurized beneath hard permafrost, as huge amounts of water were frozen into an immense ice cap at Mars's south pole.

Even as Mars was freezing over though, it likely still had seas. Remaining unfrozen on a cold world, they may have resembled the waters near Antarctica on Earth today and could have been extremely salty (via The Harvard Gazette). As Space.com explains, some studies have found that the ancient Martian ocean may have remained at least partially liquid even as the average surface temperature of Mars plummeted below freezing. Seemingly, as "recently" as three billion years ago, Earth and Mars still weren't so different.

The missing Martian atmosphere

The atmosphere of Mars was doomed from the start, and with it, any and all liquid water on the Martian surface was ultimately doomed too. The reason Mars failed while Earth survived, in a nutshell, is that the two planets are built differently. According to Science Daily, the core of a planet is what generates its magnetism, as swirling molten metals circulate, creating currents deep within the planet's heart. The heart of Mars contains two types of metallic fluid that once circulated, creating magnetism. But these fluids are like oil and water. Eventually, they separated into layers. Once they stopped churning, there was nothing to start them up again, and the magnetic field which once protected the planet mostly vanished.

As a paper in Science explains, without a magnetic field to shield it, Mars' atmosphere was left fully exposed to the solar wind. A raging torrent of charged particles spat out by the Sun, the solar wind wore away at the Martian atmosphere for millions upon millions of years, gradually stripping it away till nearly none remained. As the atmosphere was lost and the pressure dropped, more water would have evaporated and eventually been lost to space. As NPR notes, this whole process would have been compounded by another unfortunate fact: Being quite a small planet, Mars simply doesn't have much gravity. The result is that light molecules like water would find it even easier to escape into space.

Squeezing water from stone

While Mars no doubt lost a lot of water into space as its atmosphere was stripped away, that's only one explanation for where Mars' lost oceans went. In fact, a lot of that ancient water may still be right there on Mars. Except it isn't technically water anymore.

National Geographic explains how minerals can effectively lock away water, trapping it chemically inside themselves, and this could have been the fate of much of the water that used to be on the Martian surface. There may easily be an ocean's worth of water still on Mars, all sealed away inside what appears to be little more than dry stone. A Caltech press release highlights that there could be water trapped in Martian rocks to account for anywhere between a third to up to a whopping 99% of the water believed to have once been on the red planet's surface. If Mars rocks are this good at soaking up water, it could even mean that the ancient oceans were once much larger and deeper than we've been led to believe.

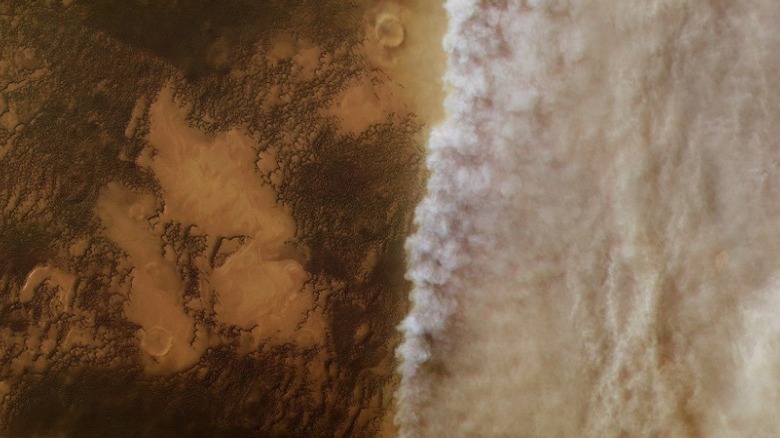

Water and dust storms

Without water, modern Mars is a dry and arid place, and it's periodically wracked by immense storms. These global dust storms are dramatic when seen from space, blanketing the planet's entire surface and hiding it from view. What's more, as NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory explains, storms like these may also contribute to Mars losing water to space.

A study published in Nature Astronomy describes how these storms contain powerful air currents which can yank ground-level air high up into the atmosphere. If this air contains any stray water molecules, they'll be struck by strong ultraviolet light from the Sun as they reach higher altitudes, eventually splitting them apart into atoms. These atoms can then very easily escape Mars' flimsy gravity and be permanently lost. This isn't just something from the past either. Even today, the storms on Mars are throwing Martian water molecules up into the sky, slowly desiccating the planet even further.

The catastrophic floods of ancient Mars

Water on Earth is nice and reliable. The sea levels change only gradually, water evaporates into clouds, and it always falls back to the world as rain. Ancient Mars, however, had no such luxury. A chaotic little planet, Mars is full of signs that its water levels in the past have been unpredictable and occasionally catastrophic. According to The Harvard Gazette, immense floods once ravaged the surface of Mars, causing ancient lakes and rivers to relentlessly overflow. These torrents are to thank for the shapes of the valleys which can still be seen on Mars, even now after the water itself has long since gone.

A study in Scientific Reports explains that these sudden deluges were caused by massive outbursts of groundwater as aquifers erupted, spilling immense amounts of water onto the planet's surface. Enough water to fill a sea dropped onto Mars all at once. But these aquifers didn't burst for no reason, as a different study in Scientific Reports mentions. The floods were triggered by asteroid impacts, causing sudden extreme amounts of heat on the Martian surface, which would defrost any nearby aquifers, causing them to shoot their water out onto the Martian surface.

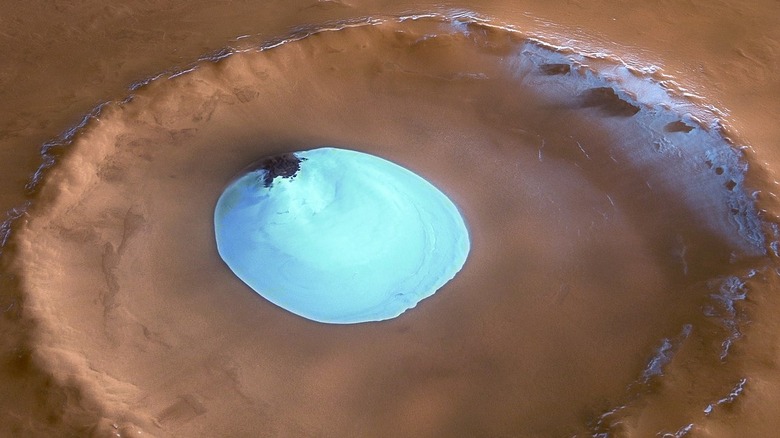

Water on modern Mars

While Mars today may be a cold and dry little world, it isn't entirely without water. That water, however, is all frozen solid as ice. Occasionally, that ice can even be found on the surface, as in one ESA image (pictured) which shows a "pool" of permanently frozen ice inside a crater near the north pole of Mars. While liquid water may evaporate at low pressure, the conditions on Mars are just right for solid ice to remain indefinitely. Ice on the surface of Mars is as solid as rock.

The polar ice caps of Mars are well known for being full of water ice (and also carbon dioxide ice), but Martian ice can be found in one other surprising place. Glaciers. Antarctic Glaciers explains how landscapes have been seen across the red planet that appear uncannily like the glaciers on Earth. On closer examination, they are full of water ice and show all the signs of flowing just like glaciers on Earth.

Most spectacular, though, is an image from NASA's HiRise spacecraft showing a relatively recent impact crater on Mars. Amid the scattered material thrown up by the impact, the image shows that the area's strewn with boulders of — you guessed it — ice! Mars, it seems, has a wealth of frozen water hidden below the ground.

Could Mars have a frozen ocean?

The fact that Mars seems to be so full of ice makes for an interesting possibility of what happened to the ancient Martian ocean. Maybe it's still there, frozen solid under the dusty red soil. The frozen ocean hypothesis, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research puts forward this idea, suggesting that the reason the northern plains of Mars are so flat is that it's all the surface of a great frozen sea. The idea even implies there could be a remaining liquid sea of extremely salty brine hiding somewhere beneath it.

Unfortunately, no spacecraft since the study was published has found anything to suggest that there's an entire frozen ocean on Mars, but there could still be enough frozen water on the planet to fill one. And while no frozen ocean has been found, Nature reports that ESA's Mars Express craft spotted a patch of the Martian surface that looks strikingly like a frozen sea.

The ocean below ground

Mars probably isn't hiding an entire frozen ocean underneath its rust-colored soil, but the Martian glaciers are likely just the tip of the proverbial iceberg for frozen Martian water. According to a study published in Icarus, a "substantial relic" of the ancient Martian ocean is likely buried under the planet's northern plains. Huge deposits of long-forgotten ice lie dormant under the ground. Hints of these lurking fragments of the ocean have already been found using orbiting spacecraft. As NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory explains, scientists have spotted frozen underground lakes all across the planet using radar signals.

Puzzlingly though, the first such lake detected on Mars appeared to contain liquid water — but this lake was spotted under the planet's south pole, in a place cold enough that it should've been completely frozen. The only possible explanation for liquid water in these places would be recent volcanism. For a long time, planetary scientists thought Mars was a dead world, with all its geological activity long gone, but there's a chance that isn't entirely true. Time reports that Mars may still be geologically active, meaning that geothermal energy may allow for pockets of liquid water, deep below ground.

This may help to explain another old mystery of Mars. Per Nature, researchers discovered methane in the atmosphere of Mars in 2004, and no one knows where it's coming from. One simple explanation is that can be released by heated rocks, which chemically react with liquid water and release methane gas.

Life on Mars

Perhaps the biggest unanswered question about Mars is whether it could have hosted life, or if it could have been in the past. If ancient Mars had a wetter climate, that definitely improves the chances of living things having once called the planet home. If Mars really did have vast ancient oceans then, per Phys Org, this increases the chances even more. As geoscientist Benjamin Cardenas explains, the lost oceans of Mars are "exactly the type of place where ancient Martian life could have evolved."

While the idea of ancient Martian microbes may seem a little outlandish, it actually makes logical sense. As Space.com mentions, around 3 billion years ago, Earth and Mars still had very similar climates, so life that could survive on Earth could likely have survived on Mars too. According to the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, the earliest traces of life here on Earth date back to 3.7 billion years ago, meaning that living things evolved on Earth while Mars was still habitable. And if life evolved here, there's no reason it couldn't have evolved there too. There's still no evidence of Martian life yet. But the possibility is tantalizing enough that many scientists are still carefully looking. Maybe there were ancient lifeforms that once called the lost oceans of Mars their home.